Introduction

Acquired angioedema (AAE) due to deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor is a rare cause of adult-onset non-urticarial mucocutaneous angioedema, characterized by recurrent episodes of cutaneous, gastrointestinal, and life-threatening laryngeal edema, similar to those observed in hereditary forms. Its presentation as acute abdominal pain, a frequent complaint in the emergency room (ER), can lead to unnecessary and potentially harmful procedures [1]. These episodes follow an overactivation of the classical complement pathway with serum C1 inhibitor (C1-INH) consumption, leading to an upregulation of the kallikrein-kinin system with bradykinin accumulation, vasodilation, and angioedema. This process can be secondary to the formation of autoantibodies that neutralize C1-INH function or due to an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder, being mono-clonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma the most prevalent [2]. While some episodes appear to be triggered by emotional/mechanical stress or viral infections, frequently there is no identifiable trigger[3].This disorder significantly impairs patients’ quality of life, so a prompt diagnosis and establishment of appropriate therapy are essential [1].

The laboratory assessment should involve the evaluation of C1-INH function, typically abnormal, and serum levels of C4, C1q, and C1-INH, generally decreased (although a normal value of the latter is not unusual). Most patients have identifiable autoantibodies against the C1-INH protein, though this analysis is not routinely available. A serum protein electrophoresis is relevant to rule out the presence of an underlying lymphoproliferative disorder [2]. Due to scarce understanding of the disease and limited published data, treatment options are essentially borrowed from hereditary forms [1]. We intend to highlight AAE as a differential diagnosis to consider in a patient presenting with acute and severe abdominal pain in the ER and the importance of excluding underlying lymphoproliferative disorders in this context.

Case Presentation

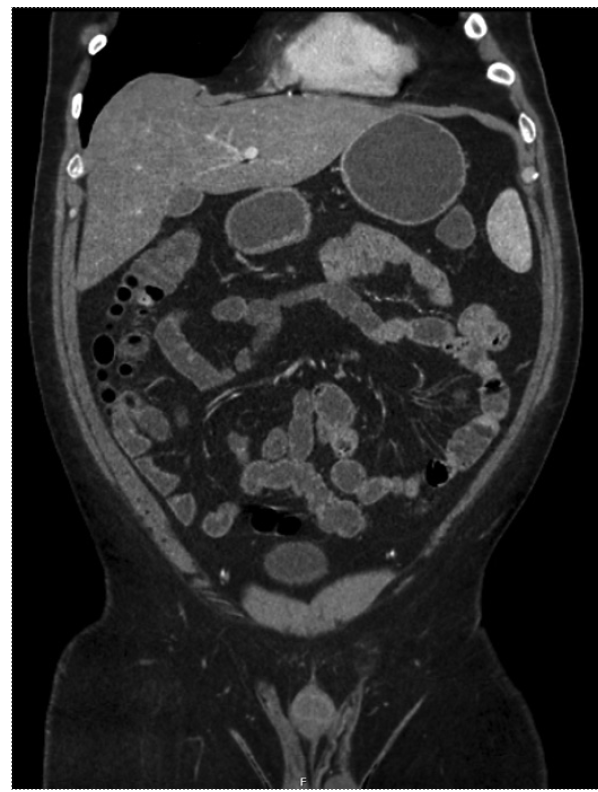

A 47-year-old male, with a personal history of smoking, obesity, and arterial hypertension controlled with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), presented to the ER with diffuse cramping abdominal pain, predominantly in the lower quadrants, which had started 15 days prior and with increasing intensity, associated with nausea and vomiting. There were no additional manifestations, namely, fever, diarrhea, respiratory, or cutaneous symptoms. Initial analytical study performed in the ER revealed lymphopenia (1,090 lymphocytes/μL) and elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (178 U/L) and C-reactive protein (37 mg/L); the remaining blood work, including hepatic, pancreatic, renal, and protein panels, was normal. Urinary sediment assessment was normal, and stool parasitological examination was negative. An abdominal ultrasound unveiled, besides hepatomegaly, hepatic steatosis, and splenomegaly, a concentric thickening of the small intestine, hyperechogenicity of ad-jacent fat tissue, and a peritoneal effusion, suggesting further evaluation with computer tomography. The latter exam reenforced the previous findings, revealing a continuous and concentric thickening of the small intestine with more than 10 cm of extension, particularly in the lower abdominal quadrants, engorgement of vasa recta, and a moderate peritoneal effusion (as shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Contrasted computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis performed in the emergency department revealing a continuous and concentric thickening of the small intestine with more than 10 cm of extension (*), particularly in the lower abdominal quadrants, engorgement of vasa recta (Δ), and a moderate peritoneal effusion (α) (coronal plane).

At this point, information obtained from clinical, analytical, and radiologic findings allowed exclusion of more frequent causes of acute abdomen, such as acute gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, cholecystitis/choledocholithiasis, appendicitis, diverticulitis, or gastrointestinal obstruction, and the main suspected diagnosis was inflammatory enteropathy versus ACEI-induced angioedema. The patient was admitted to the ward and, under symptomatic treatment, along with ACEI suspension, complete resolution was achieved in a period of 8 days. Additional assessment during the hospital stay involved a negative measurement of antibodies anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA) and antineutrophil cytoplasmic (ANCA), and endoscopic exams with biopsies, without abnormal findings, further excluding acute infectious causes, inflammatory bowel disease, and gastrointestinal malignancy. An eco-guided paracentesis revealed a peritoneal transudate, with discretely increased lymphocyte levels (417 mononuclear cells/μL and 144 polymorphonuclear cells/μL) and no other altered parameters, namely, glucose, albumin, proteins, pancreatic alpha-amylase, lactate dehydrogenase, and adenosine deaminase. Mycobacteriological assessment of the ascitic fluid was negative. Before discharge, a computer tomography enterography was performed, revealing normalization of the initial acute findings (as shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Computed tomography enterography of the abdomen and pelvis performed before patient’s discharge without the previously observed abnormalities (identical coronal plane as Fig. 1).

After referral to our Allergy and Clinical Immunology Department, a detailed anamnesis ruled out personal and family history of angioedema or urticaria. Of note, he also reported living a stressful lifestyle and a loss of about 9% of his body weight during the previous 12 months, following a voluntary increase in physical activity and a more controlled diet. Analytical study revealed persistence of the initial findings (with normalization of C-reactive protein) and low serum levels of C4 (<2 mg/dL), C1q (9 mg/dL), and C1-INH (9.2 mg/dL), together with an abnormal C1-INH function, favoring the diagnosis of AAE in detriment to ACEI-induced angioedema.

Once the diagnosis of AAE was established, it became essential to exclude secondary causes. To start with, the patient denied B symptoms, and further assessment revealed a high sedimentation rate (19 mm/h) and high beta-2 microglobulin (3.14 mg/L). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation also revealed a monoclonal gammopathy IgM/Kappa. Due to these findings, having a shared long-term follow-up in mind, the patient was referred to a Hematology/Oncology appointment.

A rare disease card containing a detailed treatment plan in case of ER admission was issued (privileging endovenous C1-INH concentrate or subcutaneous bradykinin receptor antagonist icatibant or, if irresponsive, endovenous tranexamic acid), and an ambulatory emergency and short-term prophylaxis treatment plan with tranexamic acid was provided and explained to the patient. Additionally, a request addressed to the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee was formalized for the acquisition and dispensation of icatibant for treatment of acute flares on an outpatient basis. During a 12-month follow-up, he reported 2 episodes of non-severe angioedema that resolved without specific treatment, one with facial involvement and another affecting the extremities, both associated with stressful life events.

Discussion

Acute abdominal pain is a common cause of ER admission. Despite its rarity, AAE should be regarded as a differential diagnosis and actively investigated following proper exclusion of more common diagnosis. Considering the fact that abdominal flares are less frequent than in hereditary forms, there is an even higher risk of missing AAE diagnosis in this context [4].

In the case reported, the patients’ age and absence of personal and familiar history of urticaria and/or angioedema led the ER physician toward more common causes of acute abdomen, such as acute pancreatitis, diverticulitis, and appendicitis [5]. The absence of significant analytical abnormalities, together with the radiologic findings and the personal history of ACEI intake, made the diagnosis of ACEI-induced angioedema the most plausible. Symptoms’ resolution after its suspension further corroborated this line of thought, and, on top of that, other differential diagnosis - inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic - were excluded during the hospital stay. However, the complementary study requested upon ambulatory evaluation revealed low serum levels of C4, C1q, and C1-INH, together with an abnormal C1-INH function, findings not compatible with ACEI-induced angioedema, favoring the diagnosis of AAE instead [5]. Nevertheless, although not directly linked to the etiology of this condition, the ACEI intake could have played a more indirect role by predisposing symptoms’ induction in a patient with a preexisting asymptomatic AAE.

This diagnosis, due to its association with lympho-proliferative disorders, raised concern to the existence of secondary causes. Further investigation revealed findings consistent with a monoclonal gammopathy IgM/Kappa, one of the most frequent underlying diagnoses [2], representing an increased risk of developing Waldenström macroglobulinemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and, rarely, multiple myeloma [6]. Regular evaluation of the underlying hematological abnormalities is essential to assess evolution and early detection and management of more serious diagnoses.

The practical approach to this condition might entail, besides close medical surveillance, according to each individual’s clinical evolution - specifically regarding episode’s frequency, location, and severity - treatment of acute flares, short-term or long-term prophylaxis. Due to the rarity of AAE, treatment options are essentially borrowed from hereditary forms, and their effectiveness and safety are based on limited research. C1-INH concentrate is by far the most commonly used drug to manage acute flares. Icatibant, a bradykinin receptor antagonist, and ecallantide, a recombinant peptide highly specific for inhibiting plasma kallikrein, have also been successfully used in these circumstances. Currently, there is no consensus or approved drugs for short- or long-term prophylaxis, although antifibrinolytic agents, such as tranexamic acid, and attenuated androgens have been reported to be effective treatments [2, 4]. Considering this, tranexamic acid was recommended for ambulatory management of non-severe acute flares and as short-term prophylaxis to prevent flares during planned exposure to known triggers such as minor surgical procedures, in addition to the emergency treatment plan in case of ER admission. Until the last patient’s assessment before loss of follow-up, he was not a candidate to long-term prophylaxis. Future investigation about whether novel safe therapies for hereditary angioedema are also effective for the treatment of patients with AAE is essential.

Overall data regarding long-term prognosis are lacking -available literature suggests that, in general, patients with a timely diagnosis and under clinician’s close monitoring are able to achieve partial or complete symptomatic control, either of AAE flares and underlying lymphoproliferative disorders. Nevertheless, there are many reports of fatalities due to AAE complications, particularly laryngeal edema and lymphoproliferative disorders’ evolution [4].

In conclusion, AAE should be regarded as an important differential diagnosis in patients presenting with acute abdomen in the ER, especially when more common causes are excluded. A correct and early diagnosis may represent a chance for a better prognosis.