Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (pNETs) comprise a heterogeneous group of neoplasms originating from the islets of Langerhans that exhibit distinct molecular and clinical features, with variable patterns of aggressiveness [1]. These tumours have been historically regarded as rare, but several lines of evidence support the hypothesis that the real prevalence of pNETs is much higher than that reported in population-based studies [1]. Large autopsy series have documented a pNET prevalence of 1.5-3%, mostly comprising small lesions [2, 3]. In a recent series of pancreatic surgical resection specimens for miscellaneous indications (other than pNETs), a prevalence of 4% of small incidental pNETs was reported by the pathologists [4]. The high prevalence of incidental pNETs documented in these studies supports the hypothesis that the risk of malignant behaviour is probably limited to a small fraction of cases and that most pNETs probably remain asymptomatic during lifetime [1, 4]. In fact, the incidence of pNETs has risen more than 6-fold over the last three decades, and this dramatic growth has been markedly greater for localized disease, possibly due to increased imaging diagnosis of asymptomatic, early-stage lesions [5, 6]. As diagnosis of pNETs become more frequent, it is of paramount importance to select which of these lesions will benefit from therapeutic intervention.

Clinically, pNETs are classified as functioning or non-functioning according to whether they secrete active hormones. In recent series, non-functioning pNETs represent up to 90% of all lesions [7]. Surgery is the standard of care for pNETs that cause symptoms of hormone secretion and for pNETs that are determined to pose a high risk of malignancy (including all

pNETs >2 cm) or that have established malignant features depending on their clinicopathological features and stage [1]. However, the management of incidentally

detected, non-functioning, smaller lesions (≤2cm) remains controversial. In clinical practice, since the natural history of these small tumours is largely unknown, the management strategy depends essentially on the adequate weighting of the risks of overtreatment and undertreatment [8].

In this article, the Portuguese Pancreatic Club reviews the importance of risk stratification of pNETs and presents an updated perspective on the surveillance strategy for sporadic well-differentiated pNETs. A literature search was performed through May 2023, using PubMed, Embase and Cochrane library, with the search terms “pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour/neoplasm,” “pNET/panNET/pNEN/panNEN,”“endoscopic ultra-sound,”“Ki-67 proliferative index,”“surveillance,” and “follow-up.” A cross-reference check was performed during full-text article review. Prospective studies, systematic reviews/meta-analyses and international consensus statements/management guidelines were preferred. The final manuscript was revised and ap-proved by all the members of the Governing Board of the Portuguese Pancreatic Club.

Risk Stratification of pNETs: The Present and the Future

It is extremely difficult to predict the course of disease in a patient with a pNET. Most (>90%) pNETs in clinical practice are well-differentiated low-grade (G1, Ki-67 index <3%) or intermediategrade (G2, Ki-67 index 3-20%) tumours and are associated with a relatively prolonged natural history, even when metastatic [9, 10].

One relevant point to consider is that, while histologic grade is a useful measure of prognosis (as a Ki-67 index >5% is linked to a higher risk of disease progression and postoperative recurrence), it is not an indicator of whether a pNET is benign or malignant [9, 10]. The only criteria for malignant behaviour are the presence of local invasion, metastases, or recurrent disease [10]. Taken together, disease stage (evaluated by imaging and clas-sified according to the ENETS/AJCC classification [11, 12]) and tumour grade (based on histology/proliferation index and classified according to the WHO classification [13]) are the two major independent prognostic factors and should always be assessed in a patient with a pNET [14].

Earlier classification systems from the WHO incorporated tumour size (≤2cm, >2 cm) into the staging criteria for sporadic pNETs [15]. There is evidence that larger tumours are more likely to be intermediate grade rather than low grade and that larger tumours are more often malignant and have somewhat poorer outcomes with a higher risk of diseaserecurrence[16].However, size alone cannot determine the malignant potential of these lesions: tumours <2 cm can be malignant and tumours >2cm can be benign [16]. In a recent multicenter retrospective cohort study of patients with non-functioning pNETs ≤2 cm who underwent surgery, one-fourth had at least one high-risk pathological factor (defined as Ki-67 > 3%, microvascular invasion, or positive nodal involvement, the latter present in 6% of the cases) [17]. These findings were similar to the results of a recent meta-analysis which showed that up to 20% of surgically resected small (≤2 cm) pNETs had malignant potential [18]. Given the non-negligible risk of ma-lignant behaviour even in small pNETs, it is of the utmost importance to identify other preoperative factors, other than size, that may help to stratify the risk of malignancy.

Besides size >2 cm [16] and Ki-67 index >5% [9, 10, 19], some particular imaging features may predict a higher risk of malignancy. The presence of hypoenhanced/heterogeneous vascular pattern, as may be revealed by dynamic contrastenhanced imaging techniques, has been linked to the presence of high-risk pathological features [17]. Importantly, microvessel density is inversely correlated to tumour grading in histologic samples, justifying the hypoenhanced/ heterogeneous contrast pattern in dynamic studies in higher-grade tumours [17, 20]. The presence of calcifications on preoperative imaging has also been shown to be an independent predictive factor of lymph node metastasis in well-differentiated pNETs and tends to occur in larger and intermediate-grade tumours [21, 22]. Additionally, upstream dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (due to intraductal invasion) and other signs of invasive behaviour, such as dilatation of the common bile duct, irregular borders, or invasion of adjacent vessels, are highly suggestive of underlying malignancy [17, 23]. Conversely, cystic degeneration, which occurs in about 11-19% of all pNETs, is mostly found in low-grade pNETs (probably due to intra-tumoural bleeding) and has been linked to lower nodal invasion rate and to better prognosis in comparison to solid pNETs [23, 24]. Other series have documented similar survival outcomes and similar rates of lymph node metastasis between pNETs with and without a cystic component [25, 26].

The utility of currently available circulating markers such as chromogranin A as an aid in the diagnosis or follow-up of pNETs is limited. Regarding chromogranin A, sensitivity is very low in cases of localized disease or low metastatic burden, and false-positive results are common in several medical conditions, such as inflammatory diseases, renal failure, chronic atrophic gastritis and with the use of proton pump inhibitors [27]. The NETest is a novel RNA-based assay that has been shown to be superior to chromogranin A in multiple metrics. This novel test measures several circulating tumour transcripts and outperformed other pNET biomarkers for prediction of tumour burden, disease progression, and response to therapy in a recent prospective comparative study [28]. In recent years, various techniques of molecular biology (based on tumour tissue sampling and liquid biopsy) have shown promising results by identifying relevant factors for prognosis/risk stratification of pNETs. Moreover, the determination of the molecular basis of this heterogeneous disease will be crucial to the development of personalized therapies. Importantly, the presence of DAXX/ATRX loss has been shown to be an independent negative prognostic factor, and its determination in biopsies samples may be helpful in the decision-making process for pNETs ≤2cm[29].

Role of Endoscopic Ultrasound: Guided Tissue Acquisition for Risk Stratification of pNETs

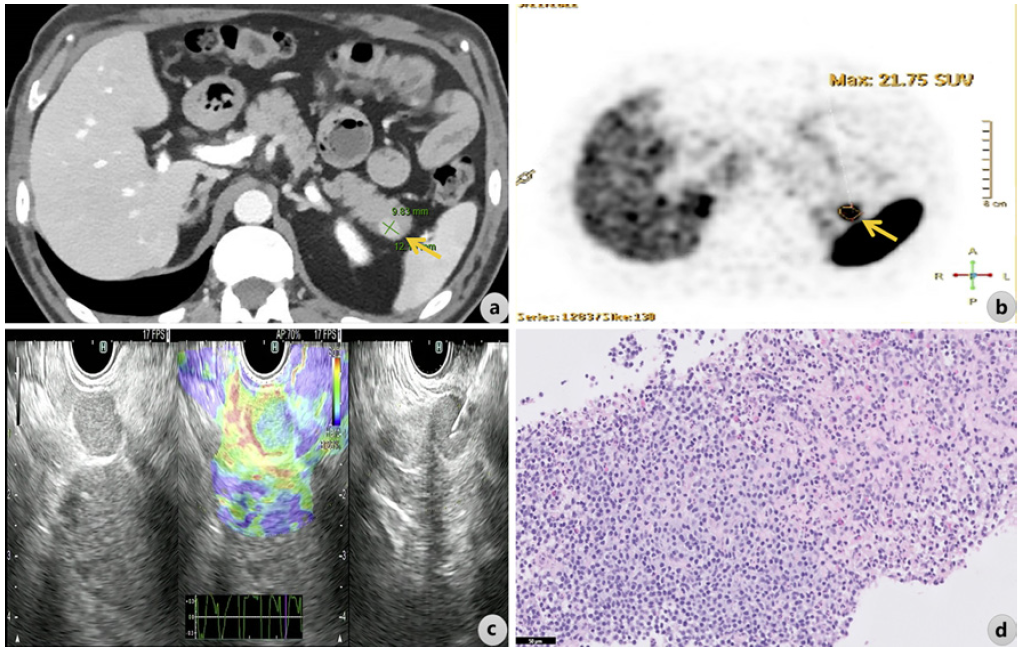

A preoperative histological diagnosis is of paramount importance for confirmation of the neuroendocrine nature of the pancreatic lesion, which needs to be differentiated from other hypervascular pancreatic lesions, such as solid-type serous cystic neoplasms, pancreatic lymphomas/plasmacytomas, hypervascular pancreatic metastases, or intrapancreatic accessory spleen lesions, some of which obviously not requiring surgical resection [30, 31]. Figure 1 shows a case involving a hypervascular nodule in the pancreatic tail that was suspected of being a pNET on computed tomography (CT) and on 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET-CT (positive for 68 Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues - SUVmax 21.8), with the final diagnosis of intrapancreatic accessory spleen following endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle biopsy (FNB). The 2020 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines [14] recommend EUS as the optimal method for the diagnosis of small pNETs due to higher diagnostic sensitivity than cross-sectional imaging tests and because it allows for histologic diagnosis. For EUS-guided sampling of these lesions, ESMO recommends the use of a cutting FNB needle, in order to acquire a tissue core for immunohistochemistry [14]. The determination of the Ki-67 proliferation index in these samples allows assessment of tumour grade, which remains an important factor to consider in the choice between surgery and surveillance in small (≤2 cm) asymptomatic pNETs, together with other factors such as patient’s age, performance status, tumour location and patient preference [14, 32]. In this regard, two recent studies have shown that the new end-cutting FNB needles outperform the traditional fine-needle aspiration (FNA) needles for Ki-67 index determination, demonstrating a closer match to surgical histology [33, 34]. This finding appears to be more significant in the assessment of small pNETs (≤2cm),whereEUS-FNA samples tend to underestimate the Ki-67 index, supporting that EUS-FNB should become the standard of care for grading small pNETs [33, 34]. There have been no prospective comparative studies evaluating different techniques of EUS-guided sampling in pNETs. Since pNETs are usually hypervascular, the non-suction/slow-pull technique has been suggested to reduce blood contamination of the specimen in a recent meta-analysis [35]. Additionally, the use of the fanning technique may be valuable for pNET sampling, particularly in large tumours that commonly present intratumoural heterogeneity of Ki-67, with focal distribution of hotspots [32].

Fig. 1 A hypervascular nodule in the pancreatic tail suspected of being a pNET was documented on contrast-enhanced CT (arrow in a) and was positive for 68Ga-labelled somatostatin analogues on 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET-CT, SUVmax 21.8 (arrow in b). Following EUS-guided FNB (c shows B-mode EUS, real-time elastography, and EUS-guided FNB), the final diagnosis of ectopic splenic tissue was made on pathology (d; H&E, scale bar corresponds to 50 µm).

Novel molecular markers associated with a higher risk of metastasis (such as ARX-positivity, loss of DAXX/ATRX, and alternative lengthening of telomeres) may potentially be evaluated in EUS-FNB core samples [36, 37]. The European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) 2023 guideline highlights that the demonstration of DAXX/ATRX loss may favour surgical resection (as it is linked to a higher risk of malignant behaviour) and may be helpful in decision-making in ≤2cmtumours [29].

How to Manage a Small (≤2 cm) Asymptomatic pNET

There is consensus among experts and guidelines that asymptomatic pNETs <1 cm can be safely followed, taking into account their indolent behaviour and extremely low metastatic potential [14, 29, 38-40]. Additionally, there is also agreement that well-differentiated pNETs >2cmshould be resected with curative intent (which should include regional lymphadenectomy) in surgically fit patients [14, 29, 38-40]. However, the management of asymptomatic pNETs between 1 and 2cm is still controversial [41]. The biological heterogeneity of these tumours poses challenges when choosing between surveillance and resection. Consensus recommendations addressing surveillance strategies are based on retrospective series with mid-term follow-up (generally <5 years) and on a limited number of systematic reviews of those studies [14, 29, 38-40]. While the 2020 ESMO guideline [14] endorses a “watchful waiting” approach for non-functioning pNETs <2cm, currentguide-lines from the ENETS [29], the North American Neuro-endocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) [40], and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network(NCCN)[39] recommend individualized management for pNETs between 1 and 2cm, based on the patient’s age, comorbidities, extent of needed surgery, tumour grade, and patient preference. Other researchers, considering the metastatic potential of pNETs according to their size, have proposed 1.5 cm or 1.7 cm as triggers for surgical resection [42, 43]. Recently, a multicentre studyreportedthatpNETs measuring 1.5-2cm had a much higher risk of lymph node metastasis than tumours <1.5 cm (17.9% vs. 8.7%), recommending surgical resection with lymphadenectomy for pNETs ≥1.5 cm [44].

Even though current guidelines recommend watchful waiting as a valid option for the management of small pNETs, a recent nationwide cancer analysis revealed that 70-80% of patients with small non-functioning pNETs have undergone resection [45]. This discrepancy between guideline recommendations and real-world data may come from the fact that there are no well-established features to accurately differentiate between low-risk and high-risk small pNETs [17]. The fear of disease progression should not be discounted, as some surgical cohorts report that 10-15% of small pNETs have malignant behaviour with regional or distant metastasis [46-48]. Our knowledge of the metastatic potential of small pNETs is based on studies that evaluated the pathological features of postsurgical specimens or studies that have compared survival between patients who have undergone upfront surgery versus those who were followed conservatively. Both study designs are associated with selection bias, and key findings have been mixed. Two systematic reviews comparing surveillance versus surgery in the management of asymptomatic small pNETs (≤2cm) have shown that active surveillance seems to be safe at least with a mid-term follow-up [49, 50]. Recently, two prospective cohort studies, the ASPEN trial [51] and the PANDORA trial [52], have shown the safety and feasibility of active surveillance of small pNETs in the short-term, with a small fraction of patients (2%) undergoing surgery (mainly due to tumour growth) after a median follow-up of 2 years in the largest study [51]. However, to evaluate the oncological safety of watchful waiting in patients with small pNETs, longer follow-up is needed.

As there is clear evidence that a subset of small asymptomatic pNETs may demonstrate malignant behaviour (and that size is not a sufficient criterion for decision-making), additional features predictive of the biological behaviour of pNETs should be sought. Javed et al. [53] have recently proposed a predictive model for lymph node metastasis in small pNETs based on tumour grade and size. In this multicentre retrospective study, G2 grade (OR 3.51, 95%confidence interval 1.71-7.22) and tumour size (per mm increase, OR 1.14, 95% confidence interval 1.03-1.25) were strongly associated with nodal disease, and the authors developed a predictive model based on these two variables to identify distinct risk groups of nodal disease [53].

In conclusion, it appears reasonable that, in the rare instance of a small pNET that demonstrates worrisome features on imaging, including any sign of invasive behaviour, upfront surgery should be offered [14, 29, 40]. In the most common scenario of a pNET between 10 and 20 mm without worrisome features on imaging, EUS-FNB is a powerful tool to evaluate tumour grade (and eventually other markers, such as ATRX/DAXX loss), which must be considered in the decision-making process [29, 32-34]. The optimal Ki-67 index cut-off for stratifying pNETs into groups at high risk and low risk of malignant behaviour has been a matter of debate, with several studies pointing to a Ki-67 index cut-off of 5% as a threshold for surgery [19]. Importantly, the potential benefit from surgery appears to be higher as the size of the tumour increases [16]. An incremental risk of nodal disease with increasing tumour size has been recently described as a continuous variable instead of a single cut-off for risk stratification [53]. Of course, the potential benefit from surgery is higher in younger patients with longer life expectancy and also whenever a less invasive surgical intervention may be feasible, as in pNETs located in the pancreatic body or tail [29, 40]. Finally, patient preference and access to long-term follow-up should also be carefully considered [40].

How to Do Surveillance

There are no prospective validation studies and no evidence-based guidelines regarding the optimal follow-up strategy [29, 38, 40]. Surveillance typically includes periodic cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI. The NCCN states that MRI should be considered over CT to minimize radiation exposure [39]. According to the ENETS consensus guidelines [29, 38], small asymptomatic pNETs (≤2cm) with alow Ki-67index (≤5%) may be followed by MRI, EUS, or CT every 6-12 months, suggesting initial surveillance at shorter intervals during the first year and extending sur-veillance intervals up to 1 year in case of stability of imaging findings [38]. The recommended follow-up protocol in the ASPEN trial consisted of MRI or CT every 6 months for the first 2 years and yearly thereafter in the absence of significant changes on imaging [8]. A more intensive follow-up protocol, as proposed in the PANDORA trial [52], resulted in lower adherence by the physicians, who considered the follow-up intervals too short. In the watch-and-wait strategy, recommended criteria for surgery include tumour growth exceeding 5 mm/year, or up to a tumour size >2cm, or the appearance of any worrisome features of invasive behaviour, such as main pancreatic duct dilatation, vascular involvement, or pathological lymph node enlargement [38, 52].

There is no established role for somatostatin analogue-based imaging (e.g., 68Ga-DOTA-NOC PET-CT) or serum biomarkers in the follow-up of small pNETs, which should be used on a case-by-case basis at the physician’s discretion [8, 29, 39, 40]. Somatostatin analogue-based imaging may be useful when there is a suspicion of tumour progression based on conventional imaging (CT or MRI), particularly to clarify the extent of disease [29, 40]. Although chromogranin A is commonly used during follow-up, its sensitivity and specificity are insufficient, and this serum marker rarely, if ever, influences management decisions [40]. The integration of novel biomarkers, such as the NETest, in the surveillance of pNETs still requires further study [40].

Key Points

Disease stage (evaluated by imaging) and WHO tumour grade (based on the Ki-67 proliferation index, determined by histology) are the two major inde-pendent prognostic factors and should always be assessed in a patient with a newly diagnosed pNET.

Besides size >2cmand Ki-67index>5%, several worrisome features on imaging (such as the pres-ence of tumoural calcifications and upstream dila-tation of the pancreatic duct) have been linked to a higher risk of disease progression, for which surgery is generally recommended.

There is consensus that asymptomatic pNETs <1cm can be safely followed.

A subset of small asymptomatic pNETs between 1 and 2 cm may show malignant behaviour and additional features predictive of their biological behaviour should be sought.

The role of EUS-FNB stands out particularly for the evaluation of small pNETs between 1 and 2 cm, allowing both histologic diagnosis, tumour grading, and, eventually, determination of ATRX/DAXX status.

The new end-cutting FNB needles outperform the traditional FNA needles for Ki-67 index determination, demonstrating a closer match to surgical histology.

An incremental risk of nodal disease with increasing tumour size has been recently described as a continuous variable instead of a single cut-off for risk stratification.

The decision to follow a watch-and-wait strategy in a patient with an asymptomatic pNET between 1 and 2cm should be made on an individual case basis, after weighing risks and benefits.

Criteria that should be considered in the decision-making process include the patient’slifeexpectancy (age and comorbidities), imaging features, WHO tumour grade, extent of surgical resection required, and patient preference. Additional markers (potentially determined in EUS-FNB samples), such as DAXX/ATRX loss, may also be helpful.

A proposed follow-up protocol for localized small pNETs consists of MRI or CT every 6 months for the first 2 years and yearly thereafter in the absence of significant changes on imaging. MRI should be considered over CT to minimize radiation exposure.