Introduction

Choledocholithiasis accounts for 8-20% of gallstone disease, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the gold standard for its treatment. The key step for successful therapeutic ERCP is selective deep biliary cannulation [1, 2]. However, standard techniques for biliary cannulation fail in 5-35% of cases, even with experienced endoscopists [1, 3]. Precut techniques have emerged as rescue procedures for accessing bile ducts. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends needle-knife fistulotomy (NKF) as the preferred technique for pre-cutting [4, 5]. Since NFK incision is made above and to the left of the papillary orifice, it avoids the contact with the pancreatic duct, being associated with a lower incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) [6-8].

Theoretically, NKF can be associated with a shorter sphincterotomy length, therefore creating the possibility of a lower success rate in the treatment of choledocholithiasis, when compared with larger sphincterotomies after standard cannulation. In the literature, to our knowledge, there is not a study designed to evaluate this specific topic. We aimed to compare the success and safety of NKF versus standard cannulation in the treatment of choledocholithiasis.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of naive patients with confirmed choledocholithiasis submitted to ERCP between 2005 and 2022. Patients were selected from a prospective database maintained at our department and allocated into two groups (sample size assuming an effect size of 10%). Exclusion criteria were partial or total gastrectomy, evidence of duodenal or gastric outlet obstruction, or history of coagulopathy.

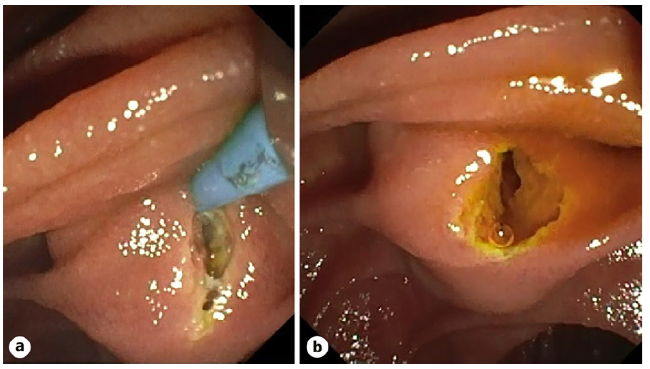

First, 179 consecutive naïve patients with confirmed choledocholithiasis submitted to NKF (as shown in Fig. 1) followed by sphincterotomy after failed standard cannulation (defined as more than 5 contacts with the papilla, more than 5 min spent while attempting to cannulate, or more than one unintended pancreatic duct cannulation or opacification) were selected (group A). The classic precut technique was not used in these patients. Subsequently, a control group (group B) with 180 naïve patients in whom standard biliary access followed by sphincterotomy was feasible was randomly selected by the investigators to match group A for stone size, number of stones, and year of the ERCP. These variables were considered important to minimize the differences in the perceived difficulty of the ERCP, potentially caused by the number or size of the stones, as well as the ability of the endoscopist.

Fig. 1 a Needle-knife is used to perform an incision 3-5 mm from the papillary orifice. b Fistula between the duodenal and common bile duct luminae.

All patients were submitted to sphincterotomy after NKF or standard cannulation. Large balloon dilatation and mechanical lithotripsy were allowed when necessary. In all patients, a stone extraction was attempted in the index ERCP in both groups. A plastic stent was placed in those patients who needed a repeat ERCP. Regarding the prophylaxis of PEP, patients received rectal indomethacin or hyperhydration with Ringer’s lactate. Pancreatic stents were placed after multiple pancreatic cannulations.

The study variables included the following parameters: age (expressed in years), gender distribution, rates of pancreatic cannulation and stent placement, occurrence of adverse events (such as bleeding, pancreatitis, bowel perforation, and cholangitis), size and quantity of stones (in millimeters), initial success rate of stone removal during the first ERCP, overall success rate considering the need for additional ERCPs, techniques employed for stone extraction, and utilization of advanced ERCP techniques (if applicable), which encompassed mechanical lithotripsy, balloon dilation, and laser lithotripsy. Additionally, the rate of repeat ERCP procedures was also assessed.

Themainoutcomeswerethe rate ofstoneremovalat baseline ERCP and adverse events. As this study was based on a prospective database, the follow-up of complications was performed in a systematic manner by the investigation team 30 days after ERCP.

Qualitative variables are summarized using absolute and rel-ative frequencies, and quantitative variables are summarized using the mean and standard deviation or the median and range, depending on their distribution profiles. The normality of the quantitative variables was assessed using the histogram distribution and the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Differences between categorical variables were tested using a χ2 test and Fisher´s exact test. For quantitative variables, student’s t test and Mann-Whitney test were used for comparisons, depending on initial normality assessment.

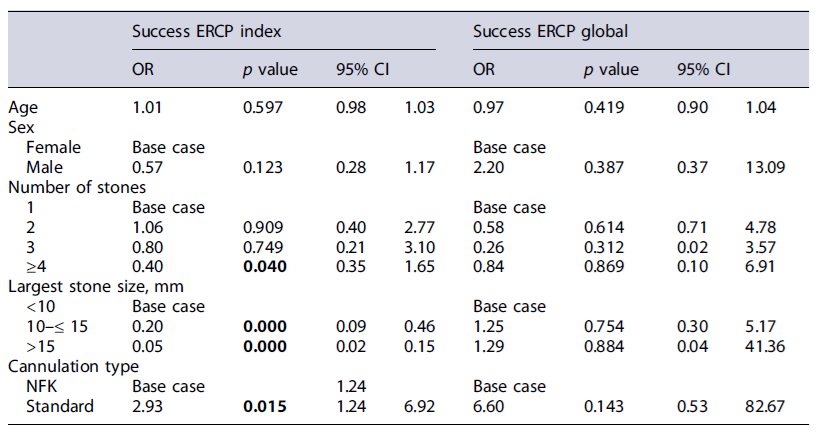

A logistic regression was performed to evaluate predictors of success and adverse events. The model contained 5 independent variables (age, sex, number of stones, largest stone size, and cannulation type) that were selected based on the clinical probability of interfering with the success of the ERCP treatment.

The null hypothesis was rejected when the test statistics p values were less than <0.05. Statistical analysis and graphics were performed using Stata software (StataCorp. 2015; Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LP).

Results

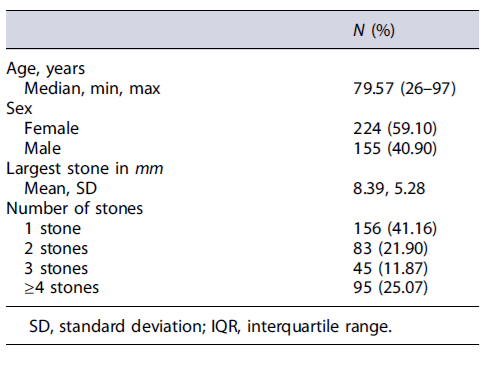

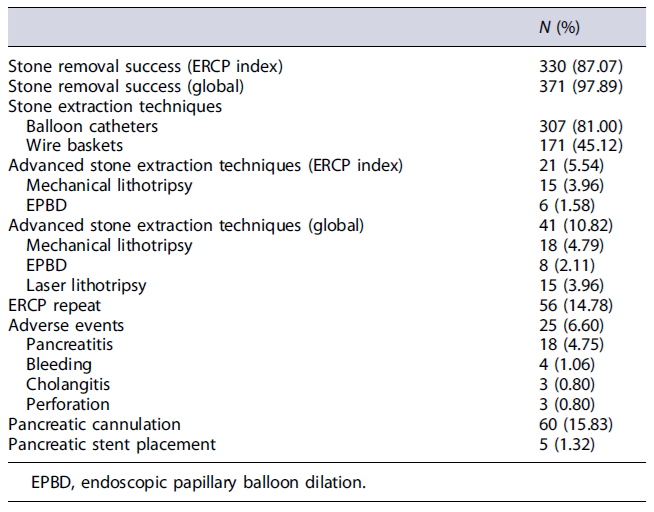

As shown in Table 1, a total of 379 patients were included (n = 224, 59.1% females, mean age 75.10 years [26-97 years]). The stone removal success rate was, globally, 87.1% in the index ERCP. In 56 (14.8%) patients, a repeated ERCP was deemed necessary, and the global success rate for complete stone extraction was 97.9%. Balloon catheters (81%) and wire baskets (45.1%) were used to extract stones. There was a need for advanced stone extraction techniques in 21 patients (5.5%) in the index ERCP and 10.8% in the repeated ERCP.

As shown in Table 2, overall, 25 procedures had complications: the rates of pancreatitis, bleeding, cholangitis, and bowel perforation were 4.8%, 1.1%, 0.8%, and 0.8%, respectively. Pancreatic cannulation was performed in 60 patients (15.8%), with 5 (1.3%) receiving a pancreatic stent.

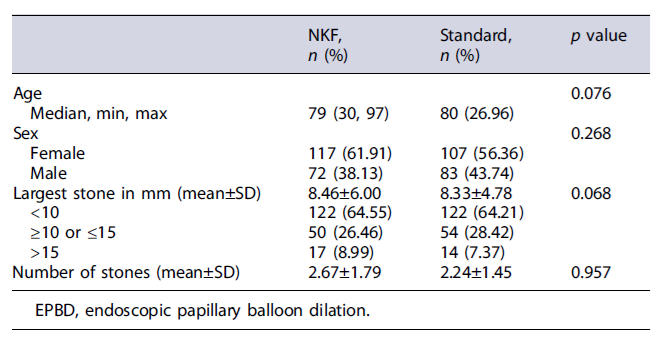

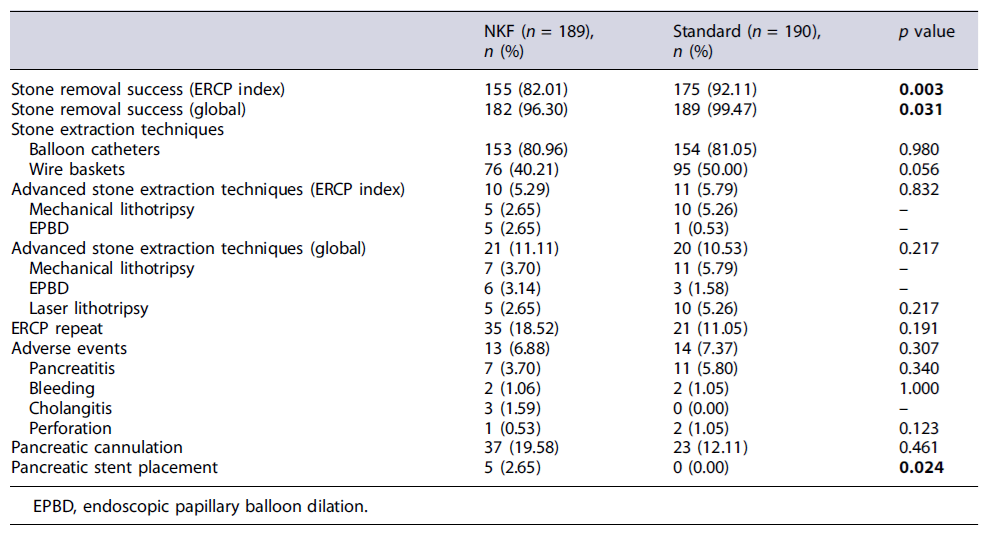

As shown in Table 3, both groups were similar regarding age, sex, and stone characteristics. The success in the index ERCP group A was significantly lower than that of the control group (82% vs. 92.1%, p = 0.003), as demonstrated in Table 4.

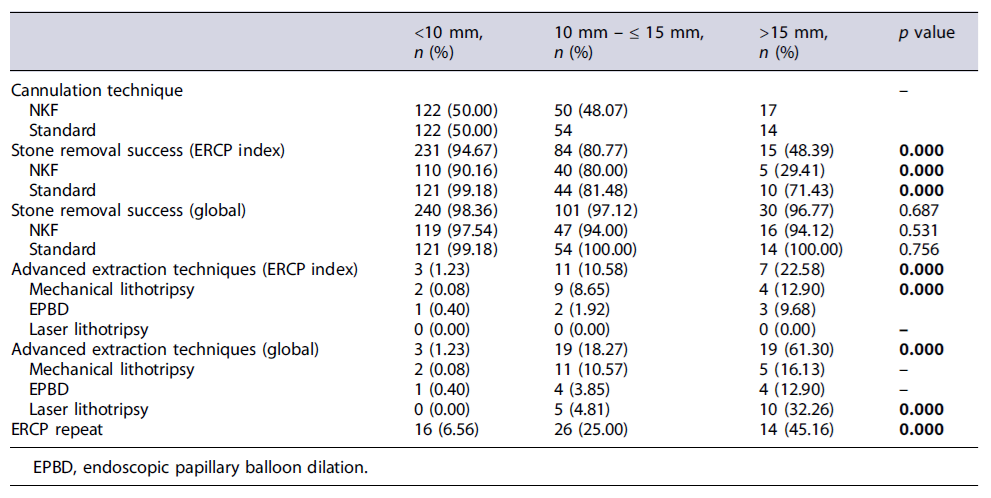

As revealed in Table 5, the stone removal success in the NKF group at the initial ERCP, for stones <10 mm, 10 mm-15 mm, and >15 mm, was 90.2%, 80%, and 29.4%, respectively (p < 0.001); in group B, it was 99.2%, 81.5%, and 71.4%, respectively (p < 0.001). Pancreatitis occurred in 3.7%of patients in group A and in 5.8% in group B (p = 0.340). In the regression analysis (Table 6), NKF cannulation was associated with a lower stone removal success rate compared with standard cannulation in the initial ERCP (odds ratio [OR] 0.34; 95% CI: 0.14-0.81; p = 0.015).

Stone size (10-15 mm and >15 mm) and having 4 or more stones were also predictors for a lower rate of stone removal in the initial ERCP (stone size 10-15 mm: OR 0.20, p = 0.000; stone size >15 mm: OR 0.05, p = 0.000; 4 or more stones: OR 0.4, p = 0.040, respectively).

Discussion

In our study, the ERCP success rate for complete stone extraction was over 87% at the index procedure and nearly 98% overall. These findings are consistent with a meta-analysis evaluating ERCP quality indicators, which found that stone extraction is successful in 88% of procedures [9].

When comparing the two groups, standard cannulation proved to have a higher success rate in stone removal at the index ERCP when compared to NKF, although both techniques demonstrated a high success rate, particularly for stones under 10 mm (>90% success rate). The difference between groups was more pronounced in stones with more than 15 mm, with 29% success rate in the index NKF ERCP and 71% in the standard cannulation group. These data could support our hypothesis that the lower success rate is probably related to a smaller biliary orifice in NKF. However, when including the repeat ERCP (global ERCP success rate), the stone size did not convey a difference. This finding could be attributed to the use of plastic stents after a failed index ERCP and an increased utilization of alternative advanced stone extraction techniques in the repeat ERCP, which might have contributed to overcoming the challenges posed by larger stone sizes, such as the length of sphincterotomy. Our findings suggest that, in patients undergoing NKF, the use of large ballon dilation or a careful extension of sphincterotomy during the first ERCP could potentially enhance its therapeutic effec tiveness and decrease the requirement for repeat ERCP. These observations align with Archibugi et al. [10], who reported that the reintervention rate for chol edocholithiasis was significantly higher in a short term after ERCP by NKF, particularly because of incomplete common bile duct clearing.

As expected, the largest stone size and number of stones were predicting factors that influence index ERCP stone removal success, though it is important to note that the number of stones only had a significant impact on the overall success rate if there were 4 or more. Recently, there has been a growing interest in the scientific community regarding the utilization of primary NKF as a first-line approach, rather than a rescue method, for cannulating the common bile duct and gaining access to the biliary tree without any contact with the papilla orifice [11]. Canena et al.’s recent meta-analysis demonstrated that primary NKF was associated with high rates of cannulation success, low rates of complications, and shorter procedural duration [12]. However, according to our findings, NFK is not as effective as the standard cannulation when it comes to treatment of choledocholithiasis, the most common indication for ERCP.

The observed complication rate in our study was 6.6%, like those reported in the literature (5.0-15.9%) [4, 5]. Notably, the incidence of PEP was 4.8%, which was lower than the anticipated range of 5-7% [5, 13]. In our analysis, the type of cannulation did not demonstrate a statistically significant impact on the occurrence of PEP. However, there was a notable trend toward a lower PEP rate in the NKF group (3.7%) compared to standard cannulation (5.8%).

Mavrogiannis et al. [14] published a prospective study aimed to compare the success and safeness of NKF (74 patients) with classic precuts (79 patients) that showed similar results as ours, meaning more repeat ERCP and lithotripsy are needed more often. Also, NKF proved to be safer than needle-knife precut papillotomy with respect to pancreatic complications.

As NKF is a rescue and expertise-demanding technique, it is impractical to develop randomized controlled trials comparing both techniques, so this study of 379 patients matched for demographic and stone characteristics can provide important data regarding the impact on the success rate of NKF in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. The retrospective design and 17-year timeframe are important limitations that precluded the inclusion of variables such as duration of the procedure or the morphology of the papilla. In the future, it would be interesting to study this matter in a prospective manner.