Introduction

Gastric cancer remains an important worldwide clinical problem. It ranks as the fourth most common cancer in males and the seventh in females [1], accounting for an estimated 1.0 million new cases in 2020 [2]. It stands as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with an estimated annual total of 768,000 deaths [2]. Gastric cancer exhibits a higher incidence among males and older people [3]. Adenocarcinoma constitutes over 90% of gastric cancers, while lymphoma, neuroendocrine, or mesenchymal tumors are comparatively less frequent [4]. Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) of the stomach are a diverse group of tumors that arise from neuroendocrine cells within the stomach, exhibiting a wide range of clinical behaviors. The classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms considers both histological features, such as differentiation and proliferation indices (mitotic account and Ki-67), to determine the grade and potential behavior of the tumor [5, 6]. The classification of these tumors has evolved to better reflect their clinical behavior and molecular characteristics. Mixed neuroendocrine-nonneuroendocrine neoplasms (MiNEN) represent a combination of both neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine components, each of which is morphologically and immunohistochemically recognizable and constitute ≥30% of the overall neoplasm [5, 6]. Most gastric neoplasm patients are diagnosed during advanced stages of the disease, presenting with common symptoms such as weight loss and abdominal pain [7]. Gastric cancer can cause minor bleeding, often culminating in chronic microcytic hypochromic anemia. However, it can also provoke major bleeding episodes in up to 5% of patients. Beyond this, emergency presentations of gastric cancer can encompass visceral perforation and gastric outlet obstruction, both of which are comparatively rare but are often associated with a higher stage of disease and poorer prognosis [8]. The authors present an unusual case of an emergency presentation of gastric cancer in a 26-year-old male.

Case Report

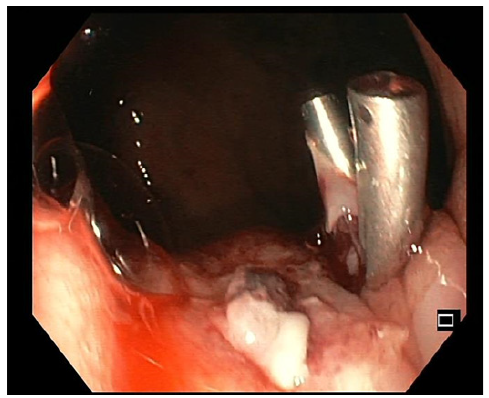

We present the case of an asymptomatic 26-year-old male, non-smoker, overweight, with no prior family history of cancer who presented to the emergency department (ED) due to a 2-day history of melena and asthenia. Although the patient appeared pale, his hemodynamic condition was stable. Anemia was evident from his blood count, revealing a hemoglobin of 7.1 g/dL. An emergency upper endoscopy showed a Forrest Ib ulcer situated at the cardia, displaying active oozing (shown in Fig. 1). An injection of 3.5 mL of diluted adrenaline (1:10,000) and an additional 3.5 mL of polidocanol 2% effectively managed the condition. The clinical presentation was assumed to be a possible Mallory-Weiss syn-drome, and the patient was discharged after a 5-day observation period. As it was an ulcer at the cardia, a follow-up endoscopy was scheduled in 12 weeks.

Fig. 1 Forrest Ib ulcer with active oozing at the cardia treated with diluted adrenaline and polidocanol injection since clip placement in the vessel was unsuccessful.

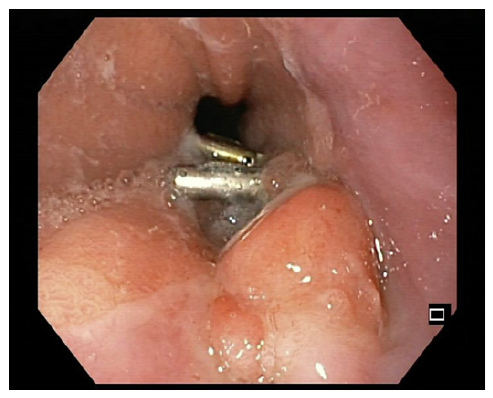

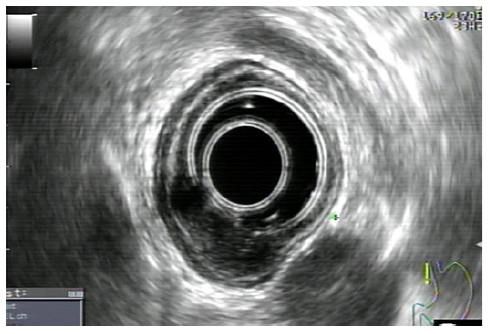

One week before the scheduled endoscopy, the patient once again presented at the ED, experiencing a recurrence of melena for 2 days and a blood count showing a hemoglobin of 11.6 g/dL. Subsequent endoscopy unveiled a distinctive 15 mm nodular subepithelial lesion at the gastroesophageal junction, with ulceration and a visible vessel at the proximal margin of the gastric mucosa. It was treated with 4 mL of diluted adrenaline injection and a clip placement on the vessel (shown in Fig. 2). An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed a homogeneous and hypoechoic lesion measuring 15 × 6 mm with well-defined limits at the deep mucosa (shown in Fig. 3). No local suspicious lymph nodes were observed. Histological examination of the biopsies of the lesion confirmed the presence of an adenocarcinoma. Subsequent computed tomography scans of the chest and abdomen revealed that the lesion retained clear cleavage plans with the surrounding structures, without suspicious adenopathies in its vicinity. After staging, the patient decided to change the health institution, which led to a month-long delay in treatment. Following a comprehensive multidisciplinary discussion, it was decided to proceed with a surgical approach, namely a distal esophagectomy and total gastrectomy.

Fig. 2 15-mm nodular subepithelial lesion at the gastroesophageal junction with ulceration in the proximal margin of the gastric mucosa.

Fig. 3 Homogeneous and hypoechoic lesion of 15 × 6 mm and well-defined limits, originated at the deep mucosa without local adenopathy’s.

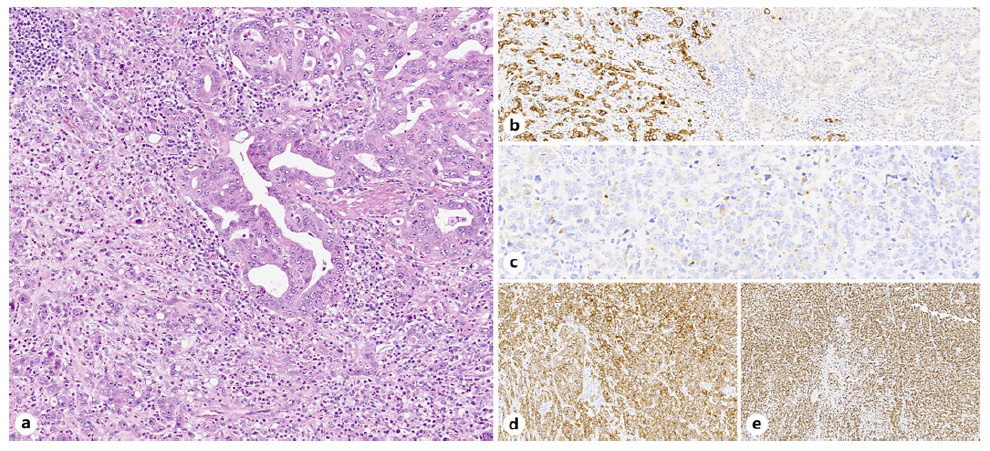

Histological examination of the surgical specimen showed a mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma composed of an adenocarcinoma with tubular/glandular pattern and signet ring cells and a large cell-type neuroendocrine carcinoma, where both components represented at least 30% of the lesion. The neuroendocrine component displayed positive staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin and a Ki-67 proliferation index exceeding 80%(shown in Fig. 4). The tumor had an infiltrative pattern and an extensive lymphovascular invasion. The neoplasia had infiltrated focally the outer muscular layers of the stomach wall and had disseminated to 3 regional lymph nodes (pT2 N2 M0) with negative resection margins (R0), therefore a stage IIb.

Fig. 4 Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasm (MiNEN), composed of an adenocarcinoma and a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. In mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma (MANEC), each component constitutes more than 30% of the neoplasm. a Tubular/glandular pattern (right) and poorly cohesive cells (left). b Synaptophysin positive. c Chromogranin positive (focally). d Cam5.2 positive. e Ki-67 proliferation index more than 80%.

The multidisciplinary tumor board decided that the patient should undergo adjuvant treatment due to the tumor stage. Currently, there is no evidence supporting adjuvant therapy for patients with resected gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Therefore, the patient underwent chemotherapy with the FOLFOX regimen for the adenocarcinoma component. Two years after the chemotherapy regimen, there is no evidence of neoplastic disease. All the genetic tests were negative for known mutations, including the CHD1 gene.

Discussion

The classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms has been improved in the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Digestive System Tumours. The presence of focal neuroendocrine differentiation may be present in any adenocarcinoma. MiNEN classification requires both components to represent ≥30%of the overall neoplasm [5, 6]. When an adenocarcinoma is accompanied by a neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) component, these neoplasms are categorized under mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma, as is the case herein [5, 6]. The neuroendocrine component is frequently characterized by poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, which can be either a small or large cell type. Various types of MiNENs arise across distinct sites throughout the digestive system, and the diagnosis for each should use site-specific terminology that portrays the nature of the components. It is noteworthy that independent neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in the same organ should not be classified as MiNEN, even if they abut one another (referred to as true collision tumors), because the MiNEN category applies only to neoplasms in which the two components are presumed to be clonally related [5]. The epidemiology of MiNEN remains uncertain because most of the literature is based on clinical cases. However, it appears to affect more males with an average age ranging from 60 to 65 years [9, 10]. A standardized therapy protocol is yet to be established for this uncommon type of tumor. Ideally, treatment should encompass surgical resection with lymphadenectomy, followed by optional chemotherapy. Usually, the aggressiveness of the tumor is determined by the endocrine component. The most beneficial chemotherapy remains a subject of controversy; the decision should be guided by the more aggressive component [9, 11]. However, guidelines for adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma differ if chemotherapy is used as an adjuvant or first-line treatment. Currently, after surgery, there is no high-level evidence supporting the benefitof adjuvant therapy in resected gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors [12]. The prognosis of MiNENs is strongly related to stage and tumor type. Commonly, the prognosis of MiNEN is poor due to their frequent diagnosis at advanced stages. Some studies suggest that patients with gastric MiNENs have a comparatively better median overall survival than those with pure neuroendocrine carcinomas. This apparent distinction could be attributed to the latter’s higher stage diagnosis [13]. Our patient’s initial presentation was marked by a life-threatening gastrointestinal bleed. Gastric cancer typically presents with non-specific symptoms such as abdominal pain and weight loss. An emergency presentation is rare, and it’s more associated with advanced stages of the disease. In this instance, the diagnosis revealed a cancer stage of IIb, further highlighting its exceptional nature. This case is also particularly uncommon due to severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). While UGIB is frequently attributable to peptic ulcers and esophageal or gastric varices, upper gastro-intestinal tract neoplasms account for approximately 3.1% of cases, with malignancy itself contributing to only 1% of severe UGIBs. When malignancies occur, they are often large and ulcerated masses [14]. The EUS has understaged the tumor, indicating a uT1 status with no nodal involvement, whereas histological examination later revealed it to be a pT2 with 3 lymph nodes involved. Studies indicate that in patients with gastroesophageal tumors, the small size of the lesion, and carcinoma with signet ring cells, there is a higher risk of lower accuracy in EUS [15, 16]. Studies are also very heterogeneous regarding accuracy of N staging. A study indicates that the diagnostic accuracy for detecting lymph node involvement has a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 67% and is higher for N2 than N1 [15]. Also, there is a time lapse between EUS and surgery of more than 1 month, and this is a very aggressive tumor, so tumor progression can contribute to this difference.

Throughout this case, we emphasize not only the patient’s young age and rarity of the cancer type but also the exceptional presentation of gastric cancer as an emergency presentation in a non-advanced stage. To our knowledge, this case constitutes the youngest patient documented with gastric MiNEN.