Introduction

In patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), adverse events may develop in up to 80% of patients, and these include Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (SOS) which result in significant morbidity and mortality [1-3]. Early diagnosis is essential to guide treatment [1, 3]. SOS results from chemotherapy or radiation-induced destruction of hepatic microvasculature during conditioning of the bone marrow [1, 3-7], and results in reduced hepatic outflow and post-sinusoidal portal hypertension [1, 5, 7].

Clinical and laboratory features of SOS usually develop ≤3 weeks after HSCT [1, 3, 6, 7]. SOS represents the most common cause of liver disease (10-60%, depending on risk factors and conditioning regimen) during the first 20 days after HSCT, although it may also present later (15-20%) [1, 3, 6, 7]. SOS may progress to systemic vasculitis and multi-organ failure [3, 4]. Severe SOS is associated with a mortality rate of up to 85% [4, 6-8].

Acute GVHD is a frequent immune-mediated adverse event after HSCT and is associated with high morbidity and mortality [9, 10]. It develops due to destruction of the recipient tissues and organs by the donor immune effector cells [9, 10]. It usually occurs ≤3 months after HSCT but may occur later [10]. Acute GVHD most frequently affects the skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract [2, 3, 9, 10].

Gastrointestinal involvement occurs in 30-75% of cases and its diagnosis is based on clinical features, imaging tests, and histopathology [3]. The diagnosis of liver GVHD is often challenging [6, 10]. Usually, cutaneous and gastrointestinal manifestations are present when jaundice develops, but liver involvement may be the presenting feature [6].

Chronic GVHD can affect any organ without a defined time limit and develops in 40-73% of patients [2, 3, 10]. It is characterized by progressive destruction of small intrahepatic bile ducts, leading to vanishing bile duct syn-drome and end-stage liver disease [10]. Although SOS and GVHD represent different entities, clinical manifestations may overlap or resemble other adverse events, which can be an important diagnostic challenge which potentially influences their timely management [3].

Case Report

A 29-year-old male patient with bone marrow aplasia since 2014 underwent HSCT in August 2022 for acute myeloid leukemia. Prophylaxis against GVHD (anti-thymocyte globulin from day (D)-3 to D-1, total dosage 378.7 mg; tacrolimus from D-2; mycophenolate mofetil from D-0 to D+56, 1000 mg 12/12 h) and against SOS (ursodeoxycholic acid 500 mg 8/8 h; acetylcysteine 300 mg 12/12 h during the entire hospital stay) was done. The donor was unrelated, with HLA correspondence of 9/10 and major AB0 incompatibility.

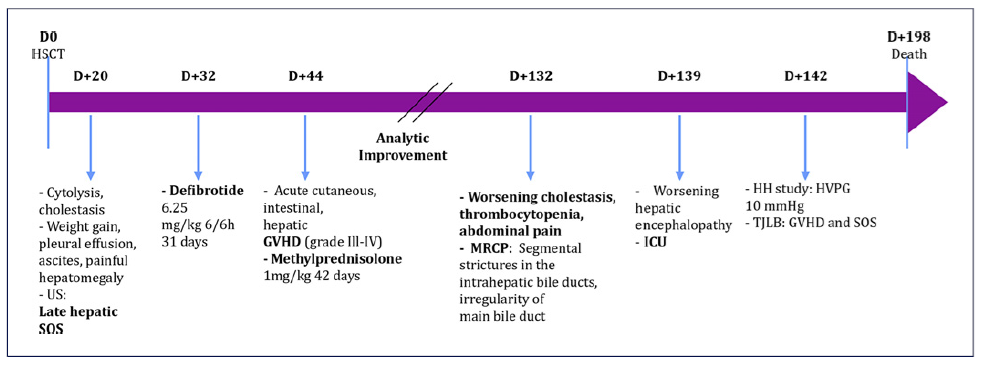

On D+20 after HSCT, he developed liver enzyme changes with cytolysis, which evolved to cholestasis, as well as weight gain, pleural effusion, ascites, and painful hepatomegaly. Ultrasound (US) findings of homogeneous hepatomegaly, thickening of the gallbladder wall, ascites, and bilateral pleural effusion without vascular hemodynamic changes were suggestive of late hepatic (severe) SOS. The patient was administered defibrotide (6.25 mg/kg 6/6 h) on D+32, this was maintained for 31 days, and it resulted in clinical improvement and a significant improvement of cholestasis (total bilirubin 1.15 mg/dL, ALP 206 U/L).

On D+44, the patient developed acute cutaneous, intestinal, and hepatic GVHD [grade III-IV - total bilirubin of 17 mg/dL, AST 119 UI/L, ALT 175 UI/L, prothrombin time (PT) 14.8 s]. He was started on methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg for 42 days), and there was a progressive improvement of cholestasis. On D+132, in the context of worsening cholestasis (total bilirubin 11.75 mg/dL, AST 198 UI/L, ALT 1028 UI/L, ALP 379 U/L, PT 11.1 s), thrombocytopenia, and abdominal pain, an MRCP was performed, and it revealed segmental strictures in the intrahepatic bile ducts and irregularity of the main bile duct (shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 MRCP-revealed segmental stric-tures in the intrahepatic bile ducts and irregularity of the main bile duct.

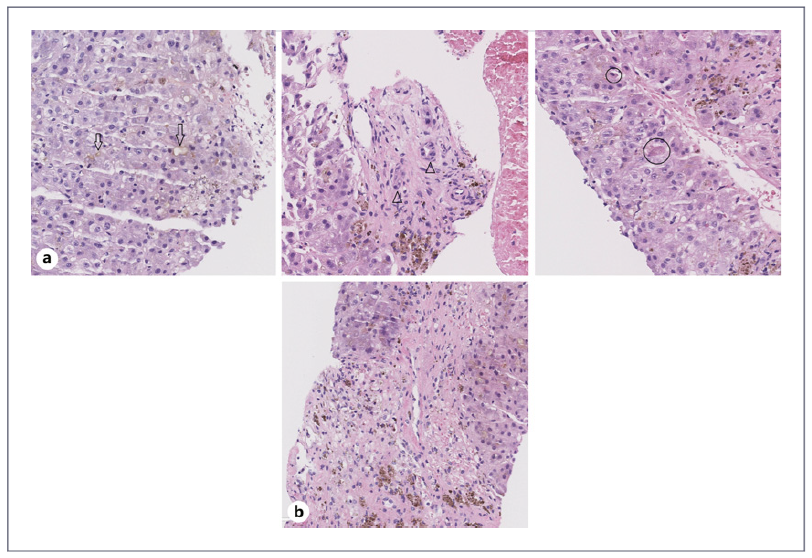

Due to worsening hepatic encephalopathy, he was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). On D+139, despite treatment with steroids, there was progressive worsening of cholestasis (total bilirubin 30 mg/dL,ALP 359U/L,AST 137UI/L,ALT359UI/L,PT11.3s)and persistence of severe thrombocytopenia (30 × 109/L/uL). On D+142, a hepatic hemodynamic (HH) study was performed by the bedside in the ICU, and it revealed a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) of 10 mm Hg. The transjugular liver biopsy (TJLB) revealed canalicular cholestasis, bile duct injury, and focal hepatocellular necrosis suggestive of GVHD, as well as features suggesting injury to centrilobular veins and centrilobular necrosis, which are observed in SOS (shown in Fig. 2a, b). There was extensive hemosiderosis. Mycophenolate mofetil (1,000 mg 12/12 h) was started. However, due to chronic GVHD and consequent septic shock, the patient died on D+195 (timeline and laboratory values shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1, respectively).

Fig. 2 Histological features of TJLB. a Features of GVHD: liver tissue biopsy with canalicular cholestasis (arrow), small bile duct injury (arrowhead), and focal hepatocellular necrosis (circle). b Features of SOS: liver tissue biopsy with central vein narrowing and extravasated erythrocytes.

Fig. 3 Timeline of patient evolution. D, day; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HH, hepatic hemodynamic; HVPG, hepatic venous pressure gradient; ICU, intensive care unit; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; SOS, sinusoidal obstruction syndrome; TJLB, transjugular liver biopsy; US, ultrasonography.

Discussion

This case exemplifies the crucial role of HH studies and TJLB in determining the etiology of post-HSCT cholestasis with the rare coexistence of GVHD and SOS. The patient had risk factors for SOS and GVHD which were mainly transplant related (allogenic transplant, unrelated, and HLA-mismatched donor) [3, 10].

The revised European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) criteria in adults include: classical SOS (≤21 days after HSCT with bilirubin ≥2mg/dL and two of the following: painful hepatomegaly, weight gain, ascites); late-onset SOS (>21 days: the same features as classical, histologically proven, and two of four criteria for classical SOS plus hemodynamic /US evidence of SOS) [4, 7].

US and Doppler US can be useful in distinguishing hepatic GVHD from SOS [3, 4] and can reveal non-specific abnormalities (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, gallbladder wall thickening [>6 mm], ascites, periportal cuffing, signs of portal venous flow abnormalities) [3, 4, 7]. The reversal of portal venous flow is more specific but often occurs late during the course of SOS [7]. CT features suggestive of SOS include periportal edema, ascites, and a right hepatic vein diameter <0.45 cm [3].

In GVHD, radiologic imaging is important for early diagnosis and treatment [2, 3]. Imaging findings are frequently non-specific and include enhancement of the biliary tract, gallbladder wall thickening, dilatation of the common bile duct, pericholecystic fluid, and biliary sludge [2, 3].

The histologic confirmation of SOS is limited to some centers and is rarely performed early after HSCT due to concerns regarding the potential complications of percutaneous liver biopsy [4, 10]. This limitation also explains why the diagnosis of acute GVHD of the liver is often one of exclusion [10]. Due to its sensitivity and specificity, liver stiffness measurement can be useful for a preclinical diagnosis of SOS and in monitoring response to treatment [4, 7].

However, HH study with TJLB is the gold standard and is safe even in patients with thrombocytopenia. It can be performed by the bedside in severely ill and unstable patients in the ICU, as was the case with our patient. It allows the measurement of HVPG and adequate histology for diagnosis [4, 6, 10, 11]. A HVPG ≥10 mm Hg defines clinically significant portal hypertension [3, 4, 6, 7]. The prognosis is especially poor when the HVPG is ≥ 20 mm Hg [3].

The typical histopathological features of GVHD include bile duct damage which may be severe, active hepatitis, and venulitis [2, 4, 10]. Liver histology may also be evaluated for drug toxicity, bacterial, viral, and fungal infection, and iron overload [3].

HSCT patients often have iron overload due to ineffective erythropoiesis coupled with increased intestinal absorption and multiple transfusions [2, 12]. It may mimic GVHD exacerbation, resulting in unnecessary continuation/intensification of GVHD immunosuppressive therapy [12, 13].

In conclusion, this case highlights the importance of HH study and TJLB in a patient who developed cholestatic hepatitis and severe thrombocytopenia after HSCT. The TJLB performed by the bedside in the ICU revealed the rare coexistence of SOS and GVHD as the causes of the cholestatic hepatitis after HSCT.