Introduction

Infection still represents the main cause of graft failure within 1 year of liver transplant (LT), despite improvements in the surgical technique, organ support, infection control, and immunosuppression regimens [1]. Nosocomial infection, occurring mainly in the first month after LT, may contribute further to morbidity and mortality [1]. The rising prevalence of multidrug-resistant micro-organisms (MDRs) worldwide may make it more difficult to treat nosocomial infections, as effective antimicrobials remain limited [2]. Strategies to prevent infections from such difficult-to-treat microorganisms frequently include institutional protocols for colonization studies.

Factors such as cirrhosis-related gut dysbiosis, exposure to prolonged courses of antimicrobials, or post-LT complications may increase the risk of MDR colonization among LT recipients [3]. Colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium has been associated with a higher risk of infections among LT recipients [4, 5]. The impact of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) colonization on the outcomes of LT recipients has been poorly studied [6, 7]. Accordingly, we hypothesized that CRE colonization may negatively impact these patients’ outcomes. Therefore, this study’s objectives were the following: (1) determine the prevalence of CRE colonization and infection among LT recipients; (2) study the association between CRE colonization and infection with clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The Central Lisbon University Hospital Center (CLUHC) Ethics Committee approved the study’s protocol and waived the individual informed consent due to its observational character (INV_447). The study’s conduct followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [8]. The study’s reporting followed the STROBE guideline [9].

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational retrospective cohort study included all adult (age ≥18 years) patients who underwent LT between January 2019 and December 2020 at Curry Cabral Hospital (CCH), CLUHC.

Definitions, Exposures, and Endpoints

Since 2018, there has been a prospective CRE surveillance protocol in the Transplant Unit at CCH as a tool to prevent cross-contamination among patients in the ward. All patients admitted for LT, whether elective (in the ward) or urgent (in the ICU), performed the first CRE rectal swab <24 h before transplantation. All patients who underwent LT were admitted to the ICU after the surgery. Following that index swab, patients were due to repeat the CRE rectal swab before ICU discharge to the ward or weekly until hospital discharge.

The CRE rectal swab was performed by the nursing staff using a specified kit (COPAN®): the humid swab was rubbed (360°movement) in the patients’ anal canal, stored in a predefined involucrum, and sent within 2 h to the CCH laboratory. Afterward, a real-time polymerase chain reaction test was performed to search for 4 genes associated with carbapenemases’ production by Gram-negative bacteria in the gut (GeneXpert®, Cepheid®): OXA48, KPC, NDM, or VIM (the IMP1 gene was only added after the study’s inclusion period, so it was not considered) [10, 11].

Patients with a CRE-positive rectal swab were placed under contact precautions in a single room or were positioned within a CRE-positive ward cohort, including patients with the same colonizing gene. Contact precautions ceased only once there were 2 consecutive (1 week apart at least) negative rectal swabs. Overall, the following patients’ data were collected from their electronic records: age, sex, LT indication, site before LT, urgent LT, comorbidities pre-LT, disease severity scores (model for end-stage liver disease with sodium correction [MELDNa] and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA]), immunosuppression post-LT (the local protocol is detailed in online suppl. Table S1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000539690), body fluids’ cultures (blood, urine, ascites, or bile as in online suppl. Table S2), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) serum viral loads (quantification limit of 34.5 × 107UI/mL) requested at clinicians’ discretion, known standard risk factors for MDR colonization or infection (hospital stay, MDR colonization or infection, and antibiotics) within 1 year prior to the index hospital admission, and CRE colonization and infection within 1 year following the index LT.

The standard LT antibiotic prophylaxis at CCH was cefotaxime (1 g every 8 h) and ampicillin (2 g every 6 h) for 24 h. There was no decontamination strategy in place for CRE-colonized patients. CRE infection empirical antimicrobial therapy was at clinicians’ discretion based on local antibiograms. Antimicrobial therapy was then adjusted at the earliest possible time based on available sensitivity tests.

Primary exposures were CRE colonization and infection within 1 year of index LT. Primary endpoint was graft failure within 1 year of the index LT. This endpoint was selected to better characterize both organs’ and patients’ morbidity and mortality during the first year post-LT. Additional outcomes considered were all-cause mortality within 1 year of the index LT and index ICU and hospital length of stay. The follow-up time period ended in October 2022.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analysis used absolute frequency (%) and median (interquartile range [IQR]) for categorical or continuous variables, respectively. Missing data across all variables were 0.2%, and no multiple imputation was performed.

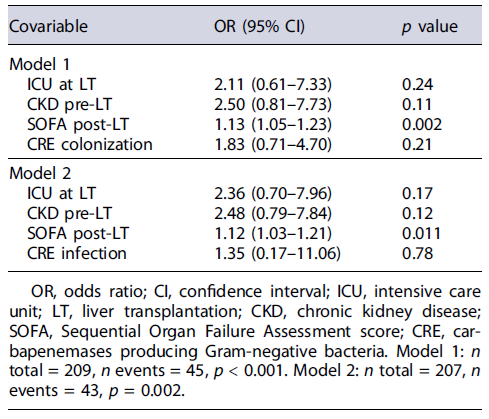

Univariable comparisons used the χ2 or Mann-Whitney tests where appropriate. Adjusted associations between CRE colonization or infection and graft failure within 1 year of index LT were studied using logistic regression. Variables were initially included in the models if deemed clinically significant and with a p < 0.10 on univariable analysis. A stepwise backward selection process was applied to build the final models. To avoid overfitting, the number of covariables admitted was restricted to one covariable per 10 events. The models’ fitness was assessed using the χ2 test. Statistical significance was defined by p < 0.05 (2-tailed). IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Between January 2019 and December 2020, there were 239 LT procedures performed in 209 patients at CCH. Thus, there were 30 retransplants during this time period (25 within 1 year of index LT).

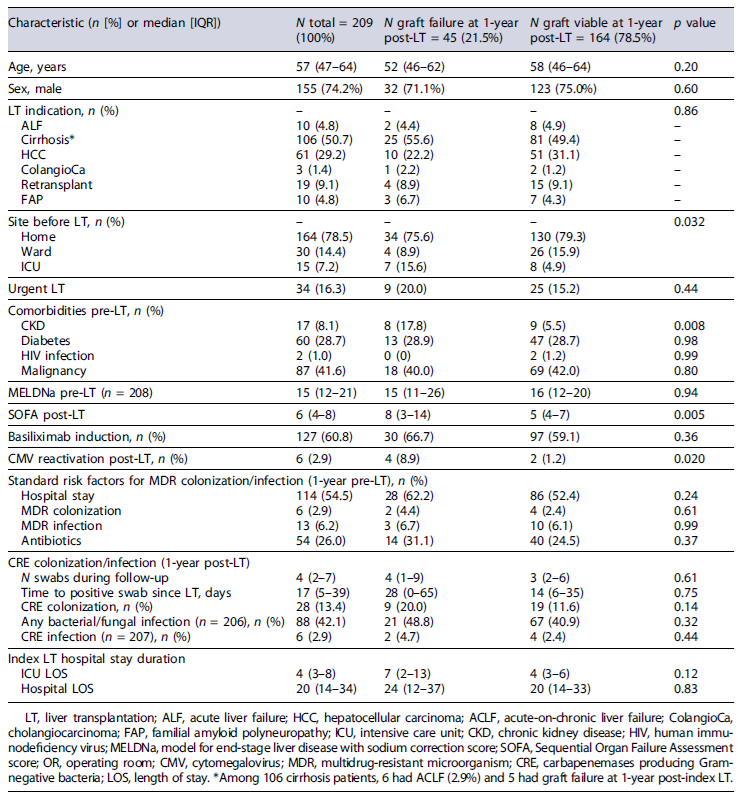

Median (IQR) age was 57 (47-64) years, and 155 (74.2%) patients were males. Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma were the leading causes of LT in 106 (50.7%) and 61 (29.2%) patients, respectively (Table 1). Etiologies of cirrhosis in the absence of hepatocellular carcinoma are presented in online supplementary Figure S1. Elective LT was performed in 175 (83.7%) patients.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent liver transplantation from January 2019 to December 2020 stratified by 1-year post-liver transplantation graft failure

Median (IQR) MELDNa pre-LT and SOFA scores upon the end of LT surgery were 15 (12-21) and 6 (4-8), respectively. Immunosuppression induction with basiliximab (antagonist of IL2 receptor) was used in 127 (60.8%) patients. All baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 1.

Exposures and Endpoints

Overall, risk factors for MDR colonization or infection identified within 1 year prior to LT were the following: previous hospital stay in 114 (54.5%), MDR colonization in 6 (2.9%), MDR infection in 13 (6.2%), and antibiotics use in 54 (26.0%) patients (Table 1). With the CRE surveillance program at CCH, 28 (13.4%) patients who underwent LT were diagnosed with CRE colonization during the first year posttransplant. During that time period, the median (IQR) number of CRE rectal swabs performed per patient was 4 (2-7). Moreover, the median (IQR) time to CRE positive rectal swab was 17 (5-39) days post-LT; in fact, 6 (21.4%) patients had a positive test since the day of index LT.

The following CRE resistance genes were identified: OXA48 in 8 (3.6%) patients, KPC in 19 patients (67.9%), and VIM in 1 (3.6%) patient. The NDM gene was not identified in this cohort. Only 1 patient showed colo-nization with 2 different CRE genes (OXA48 and KPC, with 98 days of interval). Among the 28 patients with CRE colonization, 6 (21.4%) eventually had at least 2 consecutive negative rectal swabs during the follow-up time period. The median (IQR) time between the first positive and negative CRE rectal swabs was 213 (82-530) days.

During the first year post-LT, any bacterial/fungal and CRE infections were diagnosed in 88 (42.1%) and 6 (2.9%) patients, respectively. Abdominal and blood-stream infections accounted for 33.9% (38/112) and 27.7% (31/112) of all diagnosed infections, respectively. The foci of these infections are detailed in online supplementary Table S3. The most prevalent bacteria causing these infections were Klebsiella pneumoniae (17.4%), Enterococcus faecium (12.8%), and Escherichia coli (10.5%). Among CRE infections, 4 were blood-stream infections, one was pneumonia, and another one was a urinary tract infection. Among fungal infections, 5 Candida spp. isolates (5.9%) were identified - 3causing cholangitis, one peritonitis, and another one a bloodstream infection. A complete list of microorganisms isolated is depicted in online supplementary Table S4. Finally, CMV reactivation was detected in 6 (2.9%) patients during the first year post-index LT.

MDR colonization (14.3 vs. 1.1%; p = 0.003) or infection (17.9 vs. 4.4%; p = 0.006) within 1 year prior to LT was associated with a higher frequency of CRE colonization 1-year post-LT. Also, MDR colonization (33.3 vs. 2.0%; p = 0.010) within 1 year prior to LT was associated with a higher frequency of CRE infection 1-year post-LT, but MDR infection prior to LT was not (16.7 vs. 6.0%; p = 0.33).

Among all patients included, 26 (12.4%) died within 1 year of LT. Furthermore, 19 (9.1%) required a re-transplant but survived that same time period. Therefore, graft failure within 1 year of index LT was 21.5% (45/209 patients). Median (IQR) index ICU and hospital length of stay were 4 (3-8) and 20 (14-34) days, respectively. Overall, the median (IQR) follow-up time period post-index LT was 1,079 (859-1,236) days. All exposures and endpoints are detailed in Table 1.

Association of CRE Colonization and Infection with Graft Failure

Based on univariable comparisons, patients with CRE colonization were more likely to develop any bacterial/fungal (20.5 vs. 8.3%; p = 0.011) or CRE (83.3 vs. 11.4%;

p < 0.001) infections during the first year post-LT than non-colonized ones. Furthermore, patients with graft failure within 1 year of index LT were more likely on ICU before LT (15.6 vs. 4.9%; p = 0.032), had more often CKD pre-LT (17.8 vs. 5.5%; p = 0.008), had a higher median SOFA score posttransplant surgery (8 vs. 5; p = 0.005), had more often positive blood cultures in the OR (24.4 vs. 7.9%; p = 0.002), and had more often CMV reactivation during the first year post-LT (8.9 vs. 1.2%; p = 0.020) than those alive without retransplant (Table 1).

Based on multivariable logistic regression, after adjusting for significant confounders, namely, ICU at LT, CKD pre-LT, and SOFA score post-LT, CRE colonization was not associated with graft failure within 1 year of index LT (Table 2: model 1: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) [95%CI] = 1.83 [0.71-4.70]; p = 0.21). In a similar adjusted analysis, CRE infection was also not associated with graft failure within 1 year of index LT (aOR [95% CI] = 1.35 [0.17-11.06]; p = 0.78).

Discussion

Main Findings and Comparisons with Previous Literature

In a large Portuguese cohort of LT recipients subjected to a standardized protocol of CRE screening, CRE colonization and infection rates within 1 year of index transplant were 13.4% and 2.9%, respectively. In an Italian cohort of 553 LT recipients, CRE colonization and infection rates were 25.7% and 10.3%, respectively, figures higher than what has been observed in our cohort [7]. Both country-level and institutional-level features may help explain such differences. While overall CRE prevalence may vary widely with geography, Portugal has been experiencing outbreaks, but rates reported have been lower than in neighboring Southern European countries, such as Spain, Italy, or Greece [10, 11]. Additionally, at our center, strict contact precautions have been enforced in the ICU and ward to help mitigate the risk of cross-contamination among admitted patients. Thus, we speculate that CRE colonization rates may have also benefited from this strict institutional policy.

We also found that CRE-colonized patients were more likely to develop any bacterial/fungal or CRE infections than non-colonized ones during the follow-up period. Previous literature reported on the association between CRE colo-nization and infection [7, 12]. In fact, post-LT complications, such as biliary leaks or strictures, with often difficult source control and requiring prolonged courses of anti-microbials, as well as multiple-week hospital stays, may create the ideal environment for CRE infection, especially in previously colonized patients. Given the small number of patients with CRE colonization prior to LT, we could not address the association between colonization at such timing and post-LT outcomes. Interestingly, not all CRE-colonized patients ended up developing an infection; therefore the colonization-infection relationship is far more complex than may be clinically perceived. Among other factors, post-LT evolving gut dysbiosis may play a role in this patho-physiological process [3, 12]. Namely, factors such as gut inflammation related to surgery or critical illness, antimicrobials’ pressure, or immunosuppression effects may all contribute to altering the gut microbiome.

In our cohort, almost two-thirds of LT recipients got induction immunosuppression with an anti-IL2 drug (basiliximab) and steroids; following that, almost all patients required maintenance immunosuppression with a calcineurin inhibitor (mostly tacrolimus) and steroids (tapered gradually until eventual discontinuation). Each patient’s immune status is very difficult to properly characterize at any sequential time point. Moreover, the association between immunosuppression and clinical outcomes following non-opportunistic infections remains doubtful [13]. Additionally, how clinicians adjust immunosuppressive regimens once there is an infection varies widely [14]. Therefore, it remains unclear how the immune status of these patients may have influenced CRE colonization and infection rates.

Finally, we found that neither CRE colonization nor infection was associated with graft failure within 1 year of index LT. While some studies have reported CRE infection to be associated with higher mortality, the impact of CRE colonization on mortality remains unclear [6, 15]. We speculate that lower rates of both CRE colonization and infection in our cohort may have contributed to the lack of an independent association between these factors and graft failure (an outcome more frequent than mortality). As our sample seemed somewhat comparable to other LT cohorts, in terms of demography, liver disease etiologies and severity, comorbidities, and risk factors for MDR colonization or infection, other factors may have influenced our CRE colonization and infection prevalence. For example, we speculate that our own locally implemented CRE surveillance program, in combination with enforced antibiotic stewardship and infection management protocols, may have helped reduce CRE colonization and infection prevalence and its impact on graft failure.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

Our results need to be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, this was a Southern European single-center observational cohort study, therefore prone to selection bias. However, our consecutive enrollment of patients, with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, may have helped to minimize such bias and strengthen the study’s internal validity. Second, we could not capture data on pre-LT immunosuppressive medication use or on the prescription of antimicrobials during the post-LT period, including transplant-related prophylaxis. Such data could have provided more insights regarding the risk factors for CRE colonization and infection in this context. Third, the study was designed to assess the impact of CRE colonization and infection on graft failure. Thus, while we can speculate about how our CRE surveillance program may have impacted CRE colonization and infection prevalence, this was not actually the purpose of our study [16].

Despite these limitations, our study adds to the lit-erature by documenting the recent CRE colonization and infection prevalence and its impact on clinical outcomes among Portuguese LT recipients in the context of an operational CRE surveillance program. Further studies from other jurisdictions could improve knowledge on the evolving CRE epidemiology and how it affects LT recipients’ outcomes [17, 18]. Moreover, further studies dedicated to how CRE colonization and infection affect clinical outcomes may help establish specific thresholds to locally adjust LT-related antimicrobial prophylaxis and CRE infection empirical therapy [19, 20]. Finally, further studies are needed to test how different digestive decontamination strategies could potentially modify gut dysbiosis, CRE colonization and infection prevalence, and clinical outcomes post-LT [21].