Introduction

Portal hypertension (PHT) is the main clinical manifestation of advanced chronic liver disease. Clinically significant PHT (hepatic venous pressure gradient - HVPG ≥10 mm Hg) [1] predicts complications like variceal bleeding, ascites, jaundice, and encephalopathy [2-4]. These can occur in the absence of cirrhosis (Table 1) [4, 5].

Porto-sinusoidal vascular disease (PSVD) is a rare cause of PHT and is characterized by absence of liver cirrhosis and detection of specificornon-specific histological findings, irrespective of PHT [4, 7]. The presence of other causes of liver disease does not rule it out [4]. The pathogenesis remains poorly understood. Drugs, hematologic and infectious diseases, prothrombotic and immune disorders, and genetic factors have been associated [4, 8]. Imaging and non-invasive tests like liver (LSM) and spleen stiffness measurements (SSM) have a diagnostic role, but hemodynamic study with transjugular liver biopsy (TJLB) is crucial to assess HVPG and obtain liver tissue for histopathology [4].

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), characterized by elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) (>25 mm Hg), is most commonly idiopathic, but may be associated with PHT (porto-pulmonary hypertension-PoPH). PAH and PoPH are histologically indistinguishable [9-11].

PAH can be associated with increased central venous pressure [12], which can rarely lead to downhill varices in the proximal esophagus [13]. Blood flows from the superior vena cava to the esophageal venous plexus [14]. It is a rare etiology for hematemesis (0.1%) [13], due to their localization in the proximal esophageal submucosa [14]. Treatment should be directed at the vascular obstruction’s underlying cause [15, 16].

Case Report

A 53-year-old-woman presented with a 3-day history of melena, epigastric pain and hematemesis. Medical history included obesity (BMI 34 kg/m2) and peripheral vascular disease treated with bioflavonoids. She denied fever, jaundice, choluria, alcohol consumption, and liver disease. She also denied taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anti-platelets, or anticoagulants.

Physical examination was unremarkable except for bilateral peripheral edema of the legs. Laboratory findings included severe iron deficiency anemia (hemoglobin 4.1 g/dL), platelet count 188 × 109/L, INR 1.13, albumin 4.6 g/dL, normal hepatic enzymes, and raised NT-proBNP (1,748 pg/mL).

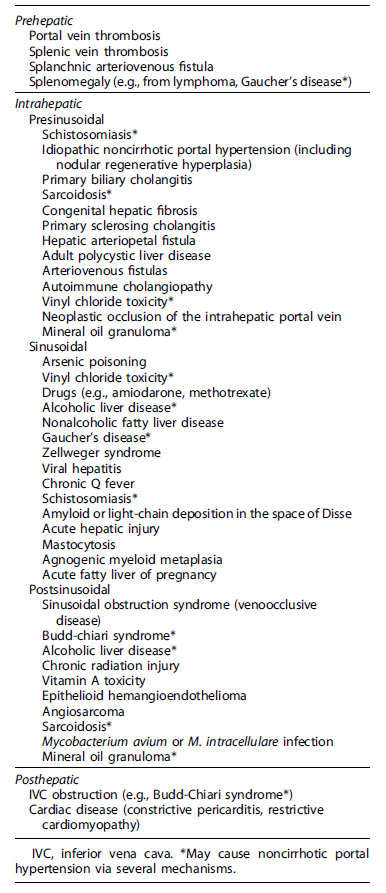

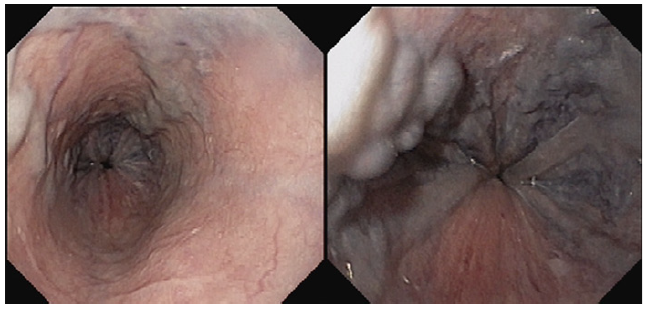

Endoscopy showed large proximal esophageal varices, without red spots, and mild portal hypertensive gastropathy (shown in Fig. 1). Abdominal ultrasound revealed slight hepatomegaly with irregular liver surface; no focal lesions; marked echogenicity of the fibrovascular axes and hilum; ectasia of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and hepatic veins; no portal vein abnormalities; mild splenomegaly (14 cm). A comprehensive chronic liver disease etiology panel was negative.

Echocardiograms revealed good systolic function; dilated right heart cavities; mild aortic and mitral insufficiency; moderate tricuspid and pulmonary insufficiency; severe PAH. Furosemide and spironolactone were instituted, with clinical improvement. Perindopril and carvedilol were introduced but the latter was suspended due to intolerance (symptomatic hypotension, lipothmia, platypneia).

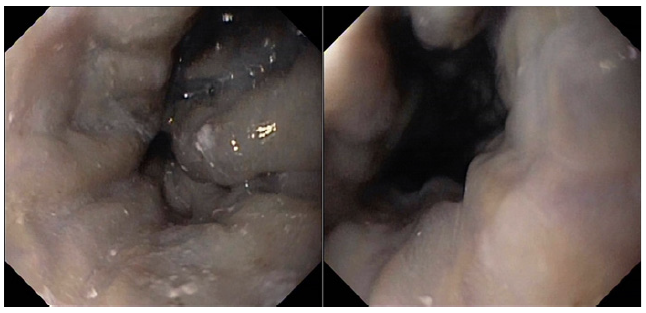

Coronary angiography ruled out coronary disease. Thoraco-abdominal computed tomography angiography showed enlarge-ment of the pulmonary artery with no evidence of thrombus, as well as absence of porto-systemic collateralizaion, portal vein thrombosis, and structural lung disease. A re-evaluation endos-copy showed large but reduced esophageal varices, without red spots (shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Large esophageal varices, reduced in size in comparison to the previous eval-uation, without red spots.

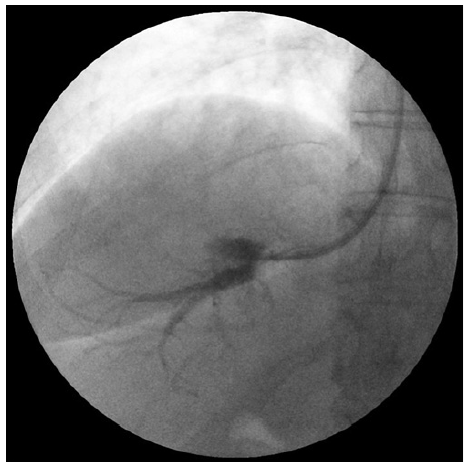

Cardiopulmonary and hepatic hemodynamic (HH) study re-vealed moderate PAH (mean PAP 40 mm Hg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure 5 mm Hg) and HVPG of 6 mm Hg, which was suggestive of non-clinically significant sinusoidal PHT (shown in Fig. 3). There were no hepatic vein-to-vein communicants detected during the HH study.

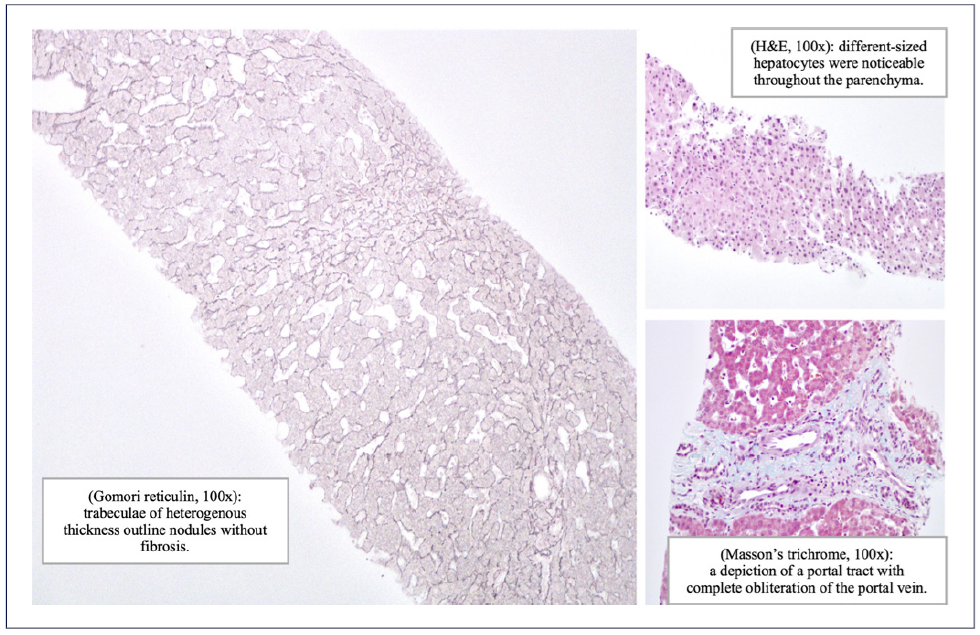

The biopsy fragments obtained with TJLB measured 48 mm in length. Histopathological evaluation revealed nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH) and obliterated portal veins, without fibrosis, suggesting PSVD (shown in Fig. 4). She was discharged on diuretics, with improvement of peripheral edema. Additionally, she was medicated with macitentan and tadalafil. She underwent variceal bleeding prophylaxis with endoscopic band ligation.

Discussion

As previously stated, diagnosis of PSVD requires histological confirmation and exclusion of liver cirrhosis [4, 17]. HH study with TJLB is often performed due to thrombocytopenia, and was key in the diagnostic process [18]. In PSVD, HVPG is normal/slightly elevated and often <10 mm Hg, due to pre-sinusoidal PHT [4, 17, 19] and presence of vena-vena communications [4, 19]. Hence, HVPG is often not correlated with events like variceal bleeding/ascites [17].

Specific histologic features include obliterative portal venopathy, NRH (present in this case) and incomplete septal cirrhosis/fibrosis [4, 17]. NRH is a nodular parenchymal transformation with hyperplastic hepatocytes surrounded by atrophic hepatocytes without fibrosis [20].

Abdominal ultrasound features of PSVD include normal/inhomogeneous liver with irregular surface; right hepatic lobe atrophy/hypotrophy; caudate lobe hypertrophy; marginal atrophy; compensatory central hypertrophy; features of PHT (splenomegaly, portosystemic collaterals, portal venous dilation); portal vein abnormalities (portal atypical thickening, hyperechoic walls, and portal vein thrombosis [PVT]) [4, 19], some of which were identified in the abdominal ultrasound performed, as is stated above.

LSM are usually normal/slightly elevated, and SSM are increased [4, 19]. LSM <10 kPa as a cut-off value has good diagnostic performance and low LSM values should prompt a biopsy [21]. A higher spleen-to-liver stiffness may be suggestive of PSVD and should indicate a HH study and TJLB to rule it out [4, 19].

Patients with PSVD and PHT are usually asymptomatic until they develop complications. Thrombocytopenia is common and transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltransferase are normal/slightly elevated, but hepatocellular function is relatively preserved (normal serum albumin and bilirubin) [4, 19].

Gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to ruptured varices is a presenting symptom in 20-40% [4, 5, 19]. Esophageal varices are frequently large and gastric varices are more common than in cirrhosis [18]. In our patient, the varices were in the proximal esophagus, a vascular territory less influenced by PHT, raising the possibility of downhill varices. Although the ultra-sound showed an irregular liver surface, hyperechoic walls of the fibrovascular axes and splenomegaly (compatible with PSVD), the IVC, and hepatic veins ectasia suggested a cardiovascular disorder. Furthermore, the patient had peripheral leg edema without ascites and the echocardiogram revealed significant cardiac valve and cavity abnormalities and severe PAH. In this case, the cardiopulmonary and HH study and TJLB were essential in confirming both PSVD and PAH.

The risk factors linking PSVD and PoPH are unknown [4], and few cases have been reported. PoPH has a multifactorial pathogenesis (genetic predisposition; pul-monary vascular wall shear stress; dysregulation of vasoactive, proliferative, angiogenic, and inflammatory mediators) [10, 11]. Patients may be asymptomatic but often present with exertional dyspnoea and may have clinical signs of right heart failure when moderate to severe disease develops [22]. In this case, the patient presented with peripheral edema. It is unclear if the level of portal hypertension is correlated with the severity of PoPH [23]. The treatment includes general measures, such as diuretics, which can reduce volume overload, and specific treatment for PAH, such as endothelin receptor antagonists (caution is advised due to hepatic impairment), phosphodiesterase subtype-5 inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogues [22, 23]. Our patient was intolerant to beta-blockers, but even if this was not the case, withdrawal of beta-blocker therapy (in the context of esophageal varices) may help to increase cardiac output and thereby help exertional dyspnoea [22, 23]. Cohort studies have demonstrated that patients with PoPH have a worse prognosis compared with patients with idiopathic PH [23].

The initial management of PSVD includes treatment of underlying conditions. Complications of PHT should be treated according to cirrhosis recommendations. Patients should be screened regularly for varices and adequate prophylaxis of variceal bleeding with endoscopic band ligation/beta-blockers should be implemented. The indications for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts and transplantation are the same as for cirrhosis [5, 7].

PVT, a frequent complication (13-45%) during follow-up [7] (increased incidence if history of bleeding and HIV infection) [4], is an indicator of worse prognosis [5]. Anticoagulation is reserved for prothrombotic disorders or PVT [4, 5, 7].

Long-term outcome in PSVD is better than in cirrhosis, given the relatively preserved hepatocellular function [4, 7]. Despite higher frequency of variceal bleeding, mortality is lower than in cirrhosis [4]. In conclusion, this case il-lustrates the uncommonly reported association between PSVD and PoPH and the importance cardiopulmonary and HH study with TJLB to confirm both.