Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic condition characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas, and its exact cause remains unknown. Among the various organs it can affect, the liver stands out as one of the most commonly involved [1, 2].

The clinical presentation of hepatic involvement in sarcoidosis can exhibit a broad spectrum, ranging from asymptomatic cases to severe complications and cirrhosis, potentially necessitating liver transplantation. In hepatic sarcoidosis, the majority of patients display mild cholestasis. Elevation in AST and ALT are lesson common.

The authors present a case of Hepatic Sarcoidosis (HS) with an unusual laboratory pattern, characterized by a pronounced elevation on liver enzymes. This case sheds light on the intricate challenges associated with diagnosis and management.

Case Presentation

A previously healthy 35-year-old Congolese female was ad-mitted to the Gastroenterology ward with a 7-month history of progressive jaundice and pruritus. Seven months prior, she had sought emergency care in Congo due to sudden dyspnea, vomiting, and decreased visual acuity, suspected to be related to poisoning. During her hospital stay, she developed generalized mucocutaneous jaundice and abdominal pain. She denied the use of medication, herbal supplements, alcohol or recreational drugs, prior blood transfusions and her family history was unremarkable. Following an inconclusive initial study, she was discharged on cholestyramine and a statin due to severe hypercholesterolemia. Over the next 7 months, she experienced a 15 kg weight loss (21%of the previous body weight), hair loss and worsening jaundice and pruritus, for which she sought medical care at our institution. Notably, upon presentation, she exhibited neither vomiting nor reported any visual or respiratory symptoms.

Upon physical examination, she exhibited generalized mucocutaneous jaundice and multiple yellowish scaly patches, primarily around the eyelids, consistent with xanthomas. No chronic liver-related signs, ascites, splenomegaly, or other relevant findings were noted.

Admission laboratory work revealed a cholestatic pattern of liver injury, with elevated total and direct bilirubin levels (16.4 mg/dL and 13.1 mg/dL, respectively), gamma-glutamyl-transpeptidase (GGT: 481 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP: 1,093 U/L). Liver transaminases were also elevated, 3-4 times the upper limit of normal (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] 141 U/L, alanine transaminase [ALT] 179 U/L). These abnormalities were associated with low 25-hydroxyvitamin D (7 U/L - normal range: 30-100 U/L) and severe hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol 735 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein 165 mg/dL, low-density-lipoprotein 55 mg/dL, triglycerides 299 mg/dL). Notably, liver function tests were within the normal range.

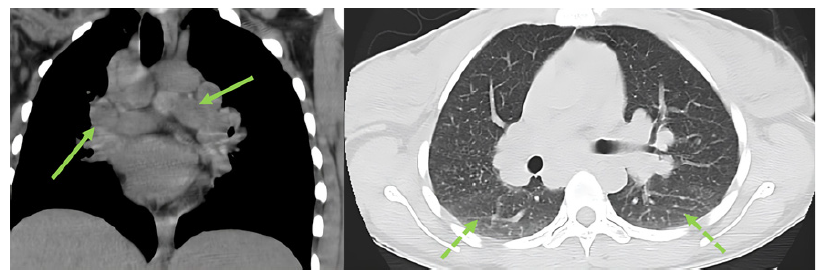

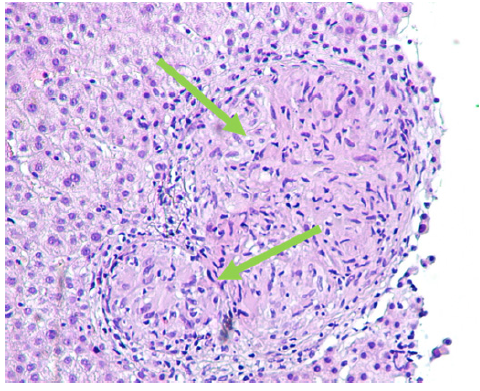

Abdominal ultrasound, contrasted tomography, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed mild hepatomegaly with a homogeneous liver and no other significant findings. Comprehensive study results were negative for infections, auto-immunity, heavy metal poisoning, metabolic diseases, and plasma cell dyscrasia (shown in Table 1). Despite the absence of respiratory symptoms, angiotensin-converting enzyme was elevated (200.7 U/L - normal range: 20-70 U/L). In this context, a chest radiological study was performed, revealing mediastinal and peribronchial adenopathies and a diffuse interstitial densification pattern in lung bases on computed tomography (shown in Fig. 1). Additionally, bronchoscopy identified whitish micronodules on the left lateral wall of the trachea and left main bronchus, with biopsies confirming non-caseating epithelioid granulomas. Immunophenotyping of bronchoalveolar lavage showed a CD4+/CD8+ lymphocyte ratio greater than 3.5. A liver biopsy was then performed (shown in Fig. 2), revealing multiple epithelioid granulomas located periportally and in the lobular areas, without necrosis. The histochemical study showed no evidence of microorganisms, including acid-fast bacilli (Ziehl-Nielsen) or fungal structures (PAS and Grocott); there was an absence of hyaline globule deposits, hemosiderin (Perls), and copper (rhodanine). In the immunohisto-chemical study, rare bile ducts were observed, and periportal he-patocytes exhibited an intermediate cell phenotype, suggesting chronic cholestasis. These findings were suggestive of HS.

Fig. 1. Thoracic computed tomography revealing multiple mediastinal and peribronchial adenopathies and diffuse interstitial densification pattern at the lung bases (see arrows).

Fig. 2. Liver biopsy revealing multiple epithelioid granulomas located periportally and in the lobular areas, without necrosis (see arrows) immunohistochemical study revealing rare bile ducts, and periportal hepatocytes with an intermediate cell phenotype, suggesting chronic cholestasis.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis work-up was negative, and the hepatic granuloma etiological study was negative for syphilis, toxoplasmosis,rubella, leptospirosis, Q fever, Schistosoma, brucella, leishmaniasis and histoplasmosis. A diagnosis of hepatic and pulmonary sarcoidosis with vanishing bile duct syndrome, hypothetically related to a toxic trigger, was assumed.

Itching was managed symptomatically with escalating doses of hydroxyzine (up to 25 mg four times daily), ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA; up to 15 mg/kg daily), cholestyramine (up to 4 g twice daily), and naltrexone (up to 50 mg daily). Targeted therapy with gradually increasing doses of prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg to 0.8 mg/kg maximum) was added to UDCA. The patient demonstrated slightly improvement in hyperbilirubinemia throughout the hospitalization, but it is noteworthy that this trend was already observed before the initiation of corticosteroid therapy. Hepatic encephalopathy was absent, and coagulation remained consistently normal. However, there was no significant improvement in ALP (809 U/L before therapy; 715 U/L on day 12 of corticosteroid), and transaminases exhibited a worsening trend during hospitalization (AST: 200 U/L before corticosteroid; 289 U/L on day 7 of corticosteroid; 236 U/L on day 14, and ALT: 232 U/L before corticosteroid and 411 U/L on day 12 of corticosteroid). Despite the lack of improvement, a decision was made on day 12 of corticosteroid therapy to escalate the dose from 25 (0.5 mg/kg) to 40 mg/day (0.8 mg/kg), resulting in a further exacerbation of transaminase levels (see online suppl. Fig. 1 at https://doi.org/10.1159/000539226). Faced with this deterioration, the corticosteroid was subsequently tapered and ultimately discontinued, leading to an improvement in the cytolysis pattern to the initial ranges. MELD score was 16 points.

Acknowledging the potential resistance to corticosteroid therapy, the medical team considered the prospect of second-line intervention. Following discussion with a tertiary center and a com-prehensive review of the literature, it was determined not to intensify the current therapy. Recognizing the hypothetical progressive course of the disease, the patient was referred to a tertiary transplant center.

At 12-month outpatient follow-up, the laboratory values and pulmonary findings remain stable. In addition to UDCA, she is currently under medication for pruritus, including optimal doses of naltrexone, hydroxyzine, and cholestyramine with a satisfactory response.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis, a condition of uncertain etiology, manifests as a granulomatous inflammation primarily affecting the lungs and, to a lesser extent, the lymphoid system. Among the organs involved, the liver ranks as the third most commonly affected organ, observed in approximately 50-65% of cases [1, 2]. This systemic disorder is characterized by non-caseating epithelioid granulomas, leading to disruption of normal tissue architecture and histology [3].

The diagnosis of hepatic sarcoidosis requires a compatible biopsy histology. It is crucial to exclude alternative causes of hepatic granulomas, such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), infectious diseases, drug reactions, and malignancies. Notably, up to 36% of granulomas may have an unknown etiology [3, 4]. In our case, differential diagnosis was even more challenging, as endemic infectious agents of Central Africa had to be excluded.

While liver involvement is common in sarcoidosis, it frequently remains asymptomatic and undiagnosed [5]. Clinical signs and symptoms become apparent in only 5-30% of individuals with hepatic involvement [3]. Approximately 15% of patients may experience pruritus due to chronic cholestasis, and abdominal pain has been reported in the same proportion [6]. Jaundice is rare, occurring in less than 5%, while fatigue is a common symptom in hepatic sarcoidosis [6, 7].

Despite being mostly benign, hepatic sarcoidosis can lead to severe complications, including severe cholestatic jaundice, portal hypertension, Budd-Chiari syndrome and cirrhosis, ultimately progressing to end-stage liver disease [5]. Abnormalities in liver tests are observed in 20-40% of cases, typically manifesting as a cholestatic pattern [8]. Elevated ALP, GGT, bilirubin (usually <5 mg/L), and slightly increased aminotransferase levels are the typical laboratory findings [8]. Elevations in AST and ALT are less common, generally remaining less than twice the upper normal limits and less severe than ALP and GGT elevations [9]. In our patient, however, a departure from the conventional pattern was observed, with a pronounced elevation of AST and ALT that exceeded the commonly observed levels in hepatic sarcoidosis. This unusual laboratory profile accentuates the heterogeneity of hepatic sarcoidosis presentations. Notably, in our case, the diagnosis was corroborated by pulmonary findings.

Hepatic sarcoidosis is distinguishable from other granulomatous disorders by the location and distribution of granulomas [10]. In sarcoidosis, the classic granuloma is predominantly situated in the portal triads, characterized by a cluster of large epithelioid cells, often accompanied by multinucleated giant cells [11]. It is worth noting that chronic intrahepatic sarcoidosis can present in a manner that mimics PBC and primary sclerosing cholangitis, and these conditions can coexist. The chronic intrahepatic cholestasis observed in sarcoidosis appears to result from progressive destruction of the bile ducts by portal and periportal granulomas. This differs from PBC and primary sclerosing cholangitis, where nonsuppurative bile duct destruction is responsible for cholestasis, and the granulomas in PBC are secondary to duct damage [3]. Histology also plays a role in differentiating between liver sarcoidosis and drug-induced liver injury (DILI). In DILI, granulomatous hepatitis is characterized by small intralobular granulomas with periportal inflammation [12].

Data for the management of liver sarcoidosis are primarily derived from small trials and case reports. Treatment is warranted in patients with symptomatic liver disease, cholestasis, or those at risk for hepatic complications [13].

Glucocorticoids are classically administered as first-line therapy, but large controlled studies conducted to date do not support the efficacy and long-term benefits of gluco-corticoids and other immunosuppressive agents [14, 15]. While steroid treatment can effectively alleviate clinical symptoms, lower liver enzyme levels, and reduce hepatomegaly, such interventions may not alter the natural course of the disease [9, 16, 17]. Notably, although a majority of patients exhibited biochemical improvement with corticosteroid therapy, with some cohorts reporting normalization of ALP and significant reduction in transaminases in almost 50% of cases, Kennedy et al. [16, 17] found that 12.5% showed no biochemical response and 8% (3/24) progressed to cirrhosis despite biochemical. In our case, it is noteworthy that, to the best of our knowledge, is the first case documented in the literature where the patient experienced an unexpected worsening of transaminase levels and ALP, highlighting the uncertainties about the optimal management of hepatic sarcoidosis, particularly in the setting of an unusual biochemical profile.

Another first-line option described in the literature for hepatic sarcoidosis is UDCA. Data demonstrate improve-ments in liver tests with the use of UDCA, although there is currently no evidence supporting its impact on long-term prognosis [7]. In contrast to the findings in a small study where UDCA demonstrated superiority to prednisone in ameliorating cytolysis syndrome, pruritus, and fatigue [18], such clear benefits were not evident in our scenario. The UDCA safety profile was also taken into account.

Second- and third-line treatments should be reserved for cases where there is a deterioration in the disease course, taking into consideration the potential hepato-toxicity and side effects. In our case, the patient has achieved a laboratory plateau, influencing our decision to watch-and-wait. Also, pruritus, the most severe complaint, has gradually receded. Despite the reported success of medications such as cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate, thalidomide, pentoxifylline, and infliximab in other cases, the limited supporting evidence regarding their efficacy and safety has led us to uphold the current treatment strategy [7, 17].

In spite of therapeutic interventions, a considerable number of patients with sarcoidosis progress to a chronic and progressive form, with 10-20% experiencing long-term complications and a mortality rate estimated at 6-7% [19]. Notably, the challenges persist even with advanced treatments, prompting consideration of liver transplantation as last resort. Posttransplant survival rates for HS patients, with 1-year and 5-year survival rates at 78% and 61%, respectively, are less favorable compared to other cholestatic liver diseases [20].

This case serves as a poignant reminder of the intricate nature of sarcoidosis and its treatment. The rarity of published data underscores the pressing need for a more comprehensive understanding of sarcoidosis to enhance diagnostic accuracy and refine therapeutic approaches.