Introduction

Hemorrhoidal disease (HD) is a common health problem, whose associated symptoms such as bleeding, pain, prolapsing, and mucus soiling can cause a significant impact on patients’ quality of life [1]. Internal HD can be classified into four degrees according to Goligher’s classification. Grade I hemorrhoids are non-prolapsing hemorrhoids. In grade II hemorrhoids, prolapse can occur during straining but is spontaneously reduced, while in grade III manual reduction is required. Last, grade IV includes irreducible hemorrhoids [1].

The incidence of HD in cirrhotic patients is similar to that in the general population, ranging from 21% to 79%[2], apparently with no correlation with hepatocellular function or portal hypertension [3]. HD in these patients is challenging for physicians because of the need to discern the bleeding originating from HD or anorectal varices [4]. Also, the unique hemostatic balance of each patient can lead to a decompensation of liver function and subsequently increase the anesthetic risk, due to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes [5]. As there is few evidence about HD treatment in cirrhotic patients, the data regarding the magnitude of adverse events risk in this special population (in comparison with general population) are also scarce [6]. Thus, an individualized assessment is crucial in these patients.

Despite the high prevalence of the disease and demanding therapeutic approach of cirrhotic patients, there are few published articles addressing this issue. Some of the studies point injection sclerotherapy (IS) as a safe and effective procedure, while contraindicating rubber band ligation (RBL) due to the potential risk of post-procedural bleeding [1, 7]. Hemorrhoidectomy is advocated as the preferred approach when bleeding hemorrhoids prove refractory to other approaches [1].

The aim of this study was to carry out a systematic review to assess the efficacy and safety of either office-based or surgical procedures in the management of HD in cirrhotic patients. To our knowledge, there are no published systematic reviews addressing this topic.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed (Medline), Scopus (Elsevier), and Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) databases was performed for papers available on October 2, 2023. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the most recent PRISMA guidelines [8] and is registered in PROSPERO database under the following code: CRD42024489679.

The search was carried out according to the following search query: ((Cirrhosis) or (“chronic liver disease”)or(“portal hypertension”)) AND ((hemorrhoid) OR (haemorrhoid) OR (“hemorrhoidal disease”)OR(“haemorrhoidal disease”)OR (sclerotherapy) OR (“rubber band ligation”)OR(“Infrared coagulation”) OR (cryotherapy) OR (“radiofrequency ablation”)OR (“laser therapy”)OR(“diathermy”)OR (“hemorrhoidectomy”) OR (“hemorrhoidopexy”)OR (“PPH”)OR(“HAL-RAR”)) AND NOT ((varices) OR (carcinoma) OR (gastric) OR (scar)).

After duplicates were excluded, all titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (S.B.P. and J.O.) for relevance and consideration of further review. Full texts were assessed by both authors for consideration of inclusion. Then, the back-search on the articles’ references was conducted, selecting two additional ones not previously captured by our query. In case of disagreement in study inclusion, the author “P.S.” performed the review.

Eligible studies included any English language primary research study published between 2003 and 2023, referring to adult patients with liver cirrhosis and reporting office-based or surgical treatments of symptomatic HD, as well as efficacy and/or safety outcomes. Review articles, systematic reviews, single case reports, and meta-analysis were excluded. Studies regarding dietary/lifestyle measures or medical therapies or conducted in pediatric or animal populations were excluded from the analysis.

Data were extracted using a defined spreadsheet and included study design, inclusion criteria, overall number of patients and percentage of those with liver cirrhosis, baseline characteristics of all included patients (age, sex, hemorrhoidal degree according to Goligher’s classification, liver cirrhosis etiology and Child-Pugh staging, applied intervention characteristics (pre-procedure preparation, procedure and adjuvant medical treatment post-procedure), follow-up period, and evaluated outcomes. Regarding efficacy outcomes, the variables considered were symptomatic improvement, patient satisfaction, and improvement in quality of life, disease recurrence/need for surgery, and/or hemorrhoidal prolapse reduction in anoscopy. As for safety outcomes, the reported adverse events were analyzed for each intervention, such as bleeding, pain, ulceration, abscess, tenesmus, local edema, and fever. Most of the studies only reported the presence or absence of each post-procedural adverse event, with the exception of Pirolla et al.’s [9] study, where pain was graded according to a scale from 0 to 10 [10], and Awad et al.’s [11] study, where rebleeding was defined as anal bleeding with two separate bowel movements or massive bleeding that required further treatment occurring 1 month after the procedure [12].

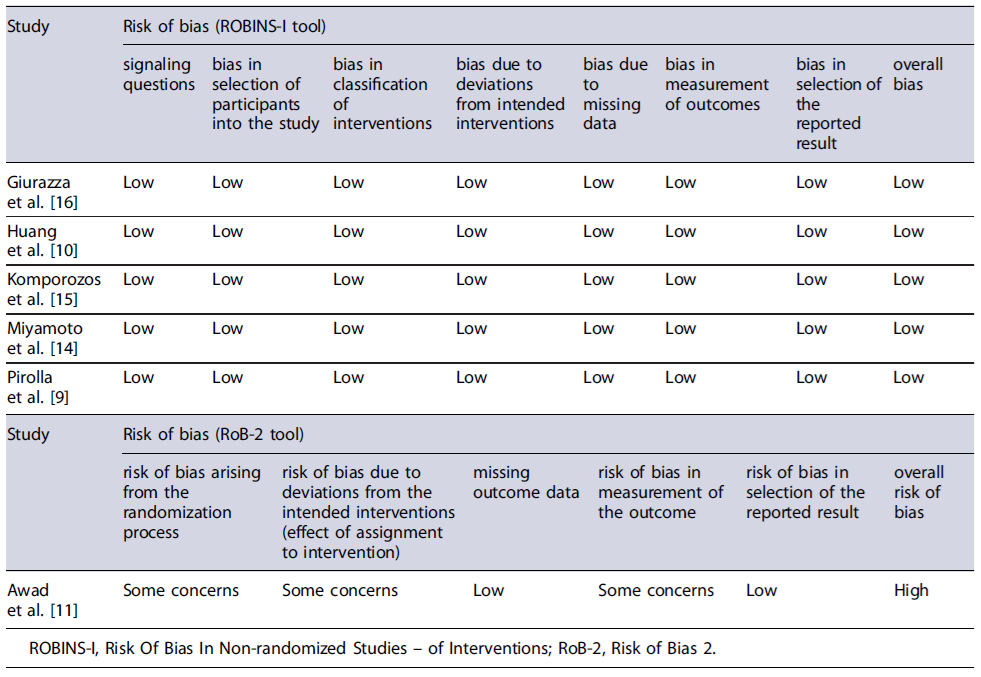

The selected studies underwent a quality assessment using either Risk of Bias 2 (RoB-2) tool [13] for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or Risk Of Bias In Nonrandomized Studies - of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool [12] for nonrandomized studies. The RoB-2 tool is divided into five potential sources of bias: bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and bias in selection of the reported result. After applying the tool, an overall risk of bias is determined, and the study is classified as Low risk of bias, Some concerns, and High risk of bias. The ROBINS-I tool evaluates studies across seven domains: bias due to confounding, in selection of participants into the study, in classification of interventions, due to deviations from intended interventions, due to missing data, in measurement of outcomes, and in selection of the reported result. A final risk of bias judgment is achieved and categorizes each study as Low, Moderate, Serious, Critical,or No information.

First, the studies were divided into two groups: office-based procedures and surgical treatments. Within these, data from each study were described individually, focusing on mean values. Subsequently, when multiple studies examined the same procedure, a descriptive comparative analysis was conducted. Meta-analysis was precluded due to the heterogeneity of outcome measures.

The primary objective of this study was to review all the current therapeutic modalities for the management of HD in cirrhotic patients. The secondary objectives were to assess the efficacy and safety of either office-based or surgical procedures in HD mangement in cirrhotic patients.

Results

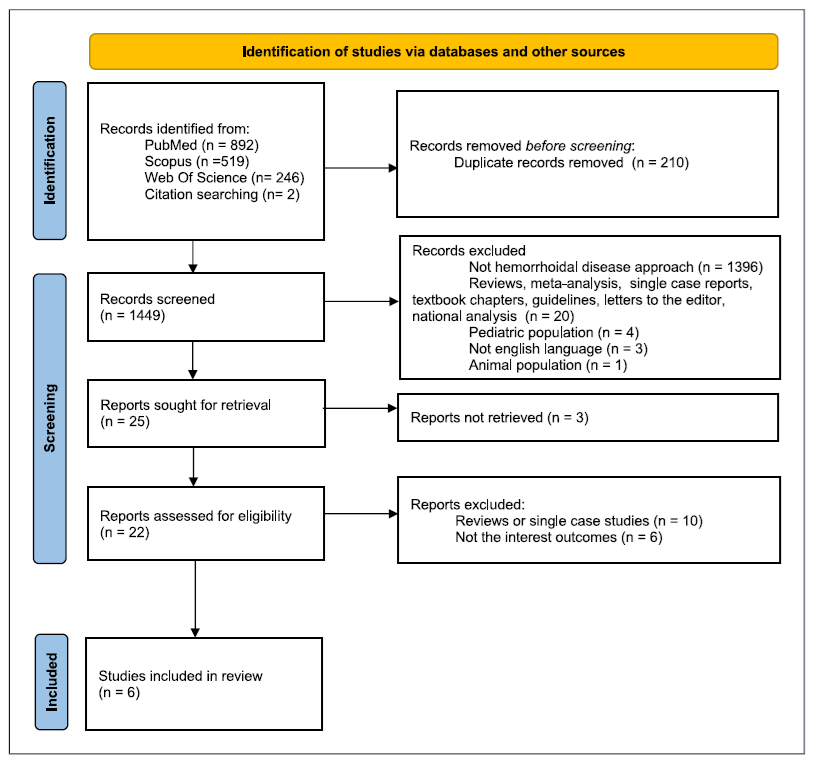

A total of 1,659 records were initially identified across PubMed (n = 892), Scopus (n = 519), Web of Science (n = 246), and citation searching (n = 2). Of these, 1,449 remained after duplicate removal. Initially screening based on title and abstract led to the exclusion of 1,424 articles and the remaining 25 were sought for retrieval. Finally, 6 studies met the inclusion criteria. The flowchart illustrating the process of study selection is described in Figure 1.

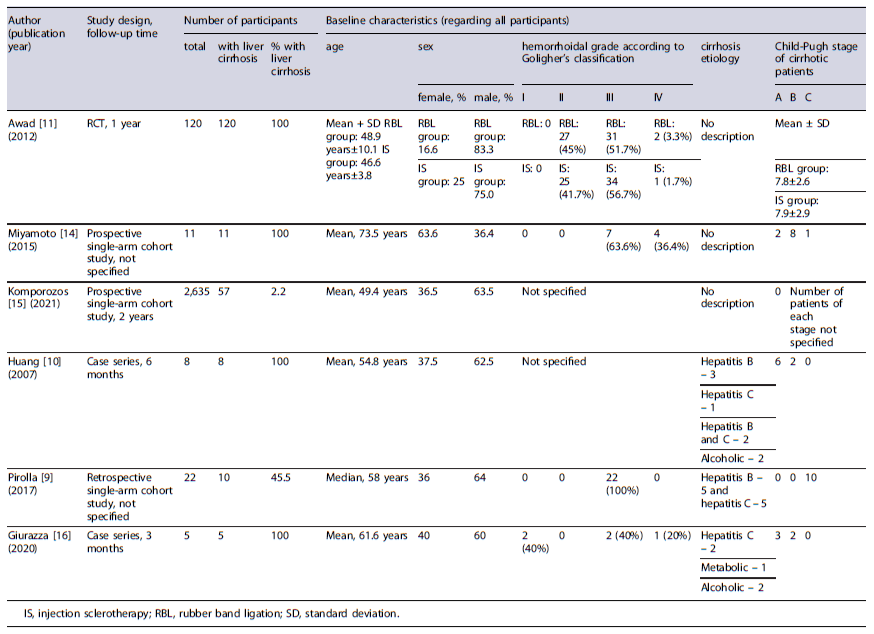

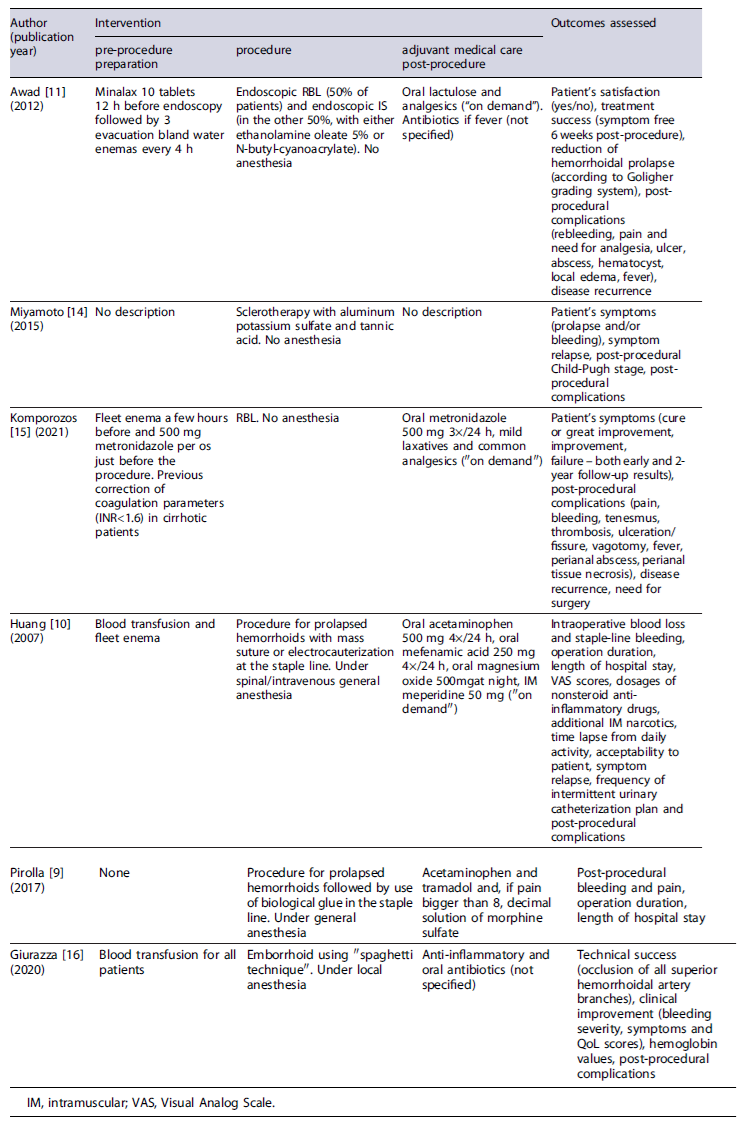

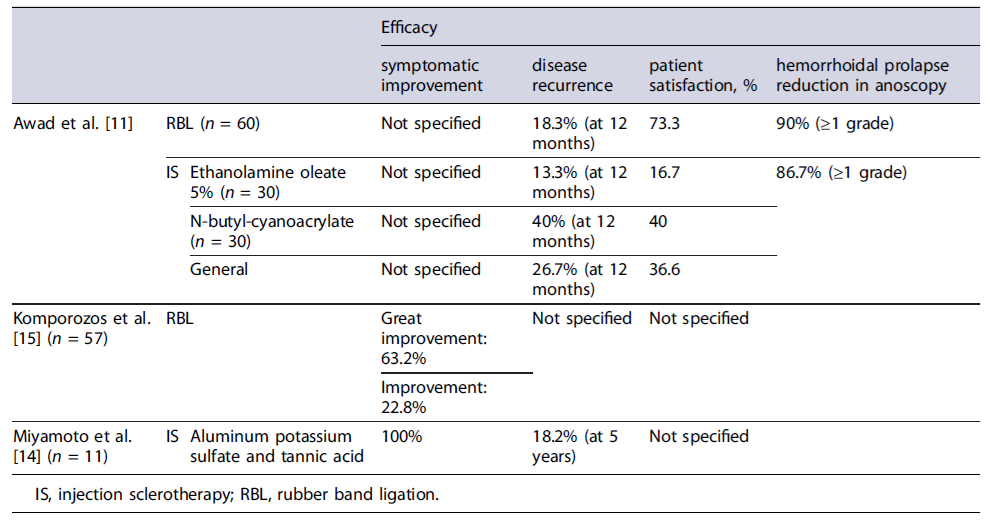

Tables 1 and 2 delineate the characteristics of the included studies. Table 3 present the results of risk of bias evaluation. Table 4 refers to efficacy outcomes.

Fig. 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews that included searches of databases and registers only.

Results of Individual Studies

Office-Based Procedures

Concerning office-based procedures, 3 articles were identified evaluating the use of RBL or IS in the treatment of HD in cirrhotic patients. The first article was an RCT by Awad et al. [11] involving 120 adult patients with liver cirrhosis aiming to compare the efficacy and adverse events of endoscopic band ligation (EBL) versus IS (ethanolamine oleate 5% - EAO - or N-butyl-cyanoacrylate).

The participants were randomly allocated into two equal groups, each undergoing one of the specified interventions, followed by a 12-month follow-up period. Both techniques allowed adequate bleeding control - demonstrated by a low rebleeding rate (10% in EBL vs. 13.3% in IS, p = 0.754) - and a decrease in disease recurrence (18.3% in EBL vs. 26.6% in IS, p = 0.530), with no significant difference observed between groups. A reduction of at least one grade in Goligher’s grading system was obtained in most cases. There were no significant differences in adverse event rates between EBL and IS, except for pain score and need for analgesia, which were higher in the IS group (1.0 ± 1.9 vs. 2.9 ± 2.1, p < 0.001 for pain and 20% vs. 61.6%, p < 0.001 for analgesia need). Comparing both sclerosing agents, EOA was associated with a significantly lower rebleeding rate (0.0% vs. 26.7% with cyanoacrylate, p = 0.010) but with a higher pain score (3.5 ± 2.0 vs. 2.3 ± 2.1 with cyanoacrylate, p = 0.025). Child-Pugh score exhibited a positive correlation with rebleeding, recurrence, and abscess formation, but only in the IS group. Overall patient satisfaction was higher in the EBL group (73.3% vs.36.6% in the IS group, p < 0.001).

A second research by Miyamoto and colleagues [14] investigated the efficacy and safety of ALTA sclerotherapy in the treatment of symptomatic hemorrhoids among 11 liver cirrhotic patients. Three-dimensional power Doppler angiography (3D-PDA) was also performed to evaluate blood flow differences in the hemorrhoidal tissue of these patients. Results showed clinical improvement for all patients. However, after 5 years, 2 cases experienced relapsing of prolapse. Post-procedural adverse events included mild bleeding (n = 2) in patients with concomitant hypervascularity in hemorrhoidal tissue in 3D-PDA evaluation, and sustained ascites (n = 3). The 3D-PDA tool has shown to predict posttreatment bleeding.

A more recent prospective single-arm cohort study by Komporozos et al. [15] assessed the efficacy and safety of RBL in the treatment of grades II to IV symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. The study enrolled 2,635 patients, including 57 with liver cirrhosis. Cirrhotic patients underwent synchronous multiple ligations in a single session. Follow-up examinations were conducted after 2 months and 2 years. Although RBL exhibited overall symptomatic improvement in the early follow-up period for the majority of cirrhotic patients, the rate of success was significantly lower when compared to non-cirrhotic patients: healing or great improvement in 63.2% (vs. 86.8%, p < 0.05), improvement in 22.8% (vs. 8.9%, p < 0.05), and treatment failure in 14.0% (vs. 4.3%, p > 0.05). The adverse event rate was not significantly different from non-cirrhotic patients, with preventive hospitalization being required in only 4 cirrhotic patients.

Endovascular Nonsurgical Procedures

Through a case series, Giurazza et al. [16] evaluated efficacy and safety of embolization of the superior hemorrhoidal artery using a novel coiling method described as “Spaghetti technique” (consisting of releasing oversized coils in a stretched fashion), in 5 liver cirrhotic patients with chronic anemia due to hemorrhoidal bleeding. All patients required transfusion prior to the intervention. Technical success, defined as the occlusion of all superior hemorrhoidal artery branches above the pubic symphysis, was achieved in all cases. At the 3-month follow-up, 4 patients (80%) mentioned clinical improvement, but there was no improvement in the Goligher grade. Symptomatic recurrence was reported in 2 patients, after 10 and 15 days, leading to a second session. No major adverse events were described. Hemoglobin levels remained stable or increased in all patients.

Surgical Treatment

Two articles were identified that evaluated stapled hemorrhoidopexy in patients with liver cirrhosis. In 2007, Huang and coauthors [10] conducted an analysis of 8 liver cirrhotic patients undergoing stapled hemorrhoidopexy (6 patients categorized as Child-Pugh A and 2 as Child-Pugh B). All patients experienced clinical improvement, although symptom relapse with mild bleeding was reported by 2 patients at 2 and 4 months. As for safety, 25% of the patients described postoperative bleeding during hospitalization, which was managed conservatively. Additional adverse events included fecal impaction (62.5%), dysuria (25%), and urinary retention requiring catheterization (37.5%). Pain was a common adverse event, evaluated using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 0 to 10 at postoperative 6 h (mean 5.5), 24 h (mean 4.3), 7 days (mean 1.8), and 21 days (mean 0.8). Additional assessed outcomes comprised median operation duration (38 min), mean intraoperative blood loss (approximately 111.3 mL), mean time lapse from daily activity (12.3 days), and median length of hospital stay (3 days). Patient’sacceptability was also reported, with 62.5% expressing it as good and 37.5% as fair.

A research led by Pirolla et al. [9] investigated the surgical outcomes of the same technique when combined with the application of biological glue in patients with grade III internal hemorrhoids and high risk of bleeding. The study comprised 22 patients, from which 10 had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. This study focused on assessing only the safety of the procedure, evaluating the presence or absence of bleeding and pain in the postoperative period. Despite the occurrence of postsurgical bleeding in 1 of the 22 patients, none of the cirrhotic patients experienced it. All patients reported pain levels below 3 on a VAS from 0 to 10. Other reported outcomes included a median operation duration of 55 min and a median length of hospital stay of 3 days.

Synthesis Results

Office-Based Procedures

Two selected studies focused on the use of RBL for treating symptomatic hemorrhoids: one by Komporozos et al. [15], which was considered to have a low risk of bias, and the other by Awad and his colleagues [11], assessed as having a high risk of bias. Both studies included data from non-cirrhotic population [15] or non-RBL treatments [11] that were dismissed from this part of synthesis (aside from adverse event rates in the Komporozos study).

The average age (mean + SD) of cirrhotic patients managed with RBL was 64.0 ± 12.5 years in Komporozos’s study and 48.9 ± 10.1 years in Awad’s article. In both studies, treated patients were predominantly male (from 83.3% to 91.2%). Exclusion criteria included colorectal carcinoma in Komporozos’s study and thrombosed hemorrhoids, anal fistulas, or perianal abscesses in Awad’s study.

To assess efficacy, the two studies applied different outcome measures. Komporozos et al. [15] divided the patients into 3 groups based on their symptoms at a 2-month follow-up visit: asymptomatic (healing or great improvement) - 63.2%, minimized symptoms (improvement) - 22.8%, or no improvement (failure) - 14%. Meanwhile, Awad and coauthors evaluated efficacy through 3 outcomes: patient satisfaction rate (73.3%), recurrence rate (18.3%), and hemorrhoidal prolapse severity reduction according to Goligher’s grading system (90% of the patients developed at least one-grade reduction after the first session).

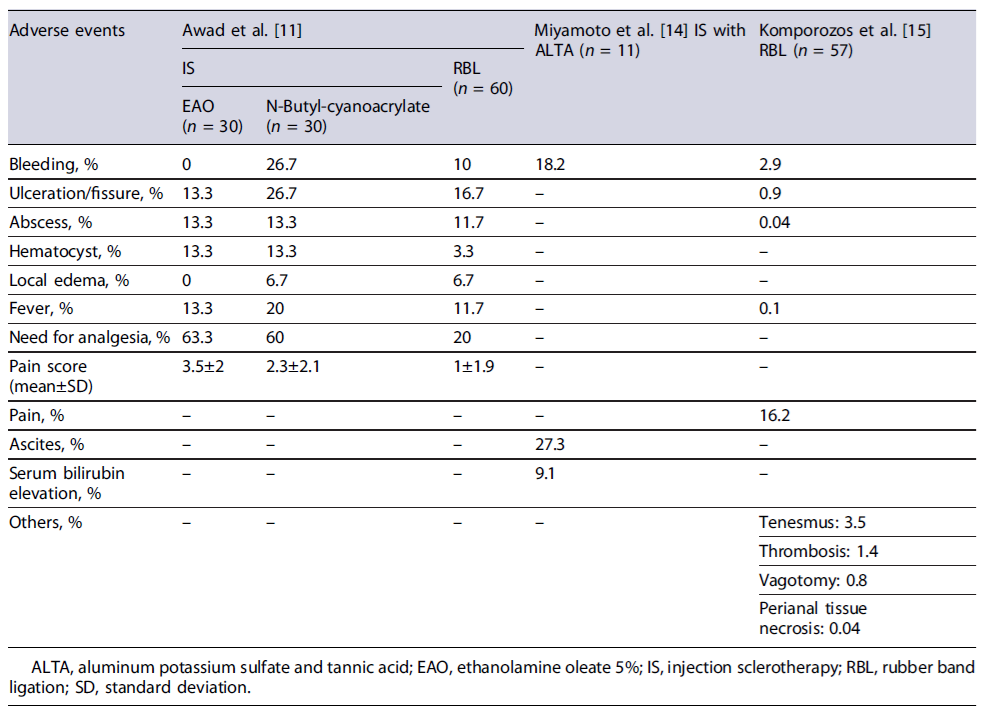

Adverse events from both studies are summarized in Table 5. Noteworthy, although Komporozos’sarticle does not address specifically the results for the cirrhotic population, these are stated as similar as those in non-cirrhotic. Therefore, the results incorporated in Table 5 include both cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic individuals.

The treatment of symptomatic hemorrhoids through IS was explored in two studies: one by Miyamoto et al.[14], with a low risk of bias, and the other by Awad and coauthors [11], with a high risk of bias. Awad’s study included information on non-IS treatments, which were excluded from this synthesis section. In Miyamoto’s study, patients had a mean age of 73.5 years and were mostly female (63.6%), while in Awad’s article, the mean age was 46.6 ± 3.8 years and the patients were predominantly male (75%).

In the Miyamoto et al. [14] study, exclusion criteria were not specified, while Awad’s study excluded patients with thrombosed hemorrhoids, anal fistulas, or perianal abscesses. Miyamoto and colleagues [14] used ALTA as the sclerosing agent, while Awad et al. [11] divided patients into two subgroups using either EAO or N-butyl-cyanoacrylate.

In Miyamoto’s study, all patients exhibited symptom improvement, but 2 patients reported disease recurrence after 5 years (18.2%). Awad’s study evaluated efficacy outcome by examining patient satisfaction rate (16.7% for EAO vs. 40% for N-butyl-cyanoacrylate), recurrence rate at the 12-month follow-up visit (13.3%for EAO vs. 40% for N-butyl-cyanoacrylate), and reduction in the severity of hemorrhoidal prolapse according to Goligher’s grading system (86.7% showed at least a one-grade reduction after the first session). Post-procedure adverse events from both studies are detailed in Table 5.

Endovascular Nonsurgical Procedures

The singular study discussing the emborrhoid technique for treating symptomatic hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patients is authored by Giurazza et al. [16], and it was previously described in this review.

Surgical Treatment

Two of the chosen research studies focused on em-ploying stapled hemorrhoidopexy for treating symp-tomatic hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patients - one authored by Pirolla et al. [9] and the other by Huang and collaborators [10]; both were assessed as having a low risk of bias. The age of the included patients was 58 years (median) in Pirolla’s study and 54.8 years (mean) in Huang’s article. In both, most patients were male (from 62.5% to 64%). Pirolla’s exclusion criteria were not specified, while Huang’s study excluded patients with concomitant anal fissure, abscess, fistula, and/or prominent external component.

Both studies evaluated safety outcomes assessing post-procedural bleeding rate and pain levels. Pirolla’s research reported a nil post-procedural bleeding rate, while Huang’s article documented a 25% bleeding rate. In Pirolla’s study, all patients experienced pain levels below 3 in a VAS score from 0 to 10, although the timeframe for evaluation was unspecified.Conversely,Huang’s study assessed pain at four distinct postsurgery intervals (6 h, 24 h, 7 days, and 21 days). During the initial 6 h, the mean VAS score was approximately 5.5, decreasing to about 1.8 at 7 days post-procedure.

Discussion

With regard to office-based procedures, specifically RBL, research on cirrhotic patients indicates that this intervention is effective, achieving cure rates of 63.2% [15], closely resembling the approximately 70% cure rates reported in the general population [17]. In the cirrhotic population, this technique has also demonstrated a 12-month recurrence rate of approximately 18.3%, which is notably lower than the 37.5% recurrence rate reported in the HubBLe trial for the general population [18] where there was a need for multiple ligation sessions within the period of 1 year. Concerning safety, the most commonly reported adverse events across the included studies were pain, bleeding, ulceration/fissure, fever, abscess, and local edema - which aligns to those documented in the general population [19]. When assessing adverse event rates in both studies addressing the use of RBL in cirrhotic patients, Awad et al. [11] showed higher adverse event rates than those documented by Komporozos et al. [15]. Several factors could account for this difference, including that adverse event rates were not specifically provided for the cirrhotic population in Komporozos’s study, and can possibly be slightly higher, although not significantly different. One of the major differences between the results achieved by the two studies was the post-procedural bleeding rates (2.9% in Komporozos vs. 10.0% in Awad). Although this difference may initially appear to result from the pre-procedural correction of coagulation parameters based on INR in cirrhotic patients in Komporozos’sstudy, recent clinical evidence showed that correcting any coagulopathy or platelets levels before a high bleeding risk procedure in cirrhotic patients does not preclude or reduce the rate of clinically significant procedure-related bleeding [20]. In fact, in most cases, laboratory evaluation of hemostasis for this purpose is not indicated, since the post-procedural bleeding risk cannot be accurately predicted [20]. In summary, when managing liver cirrhotic patients with concomitant HD, RBL proves to be a safe and successful technique, yielding a patient satisfaction rate of 73.3% [11].

When assessing IS as a treatment for HD in cirrhotic patients, the studies included explored the use of three sclerosing agents - ALTA, EAO, and N-butyl-cyanoac-rylate. All agents demonstrated clinical improvement, yet with varied recurrence rates. At 12 months, recurrence rates ranged from 13.3% for EAO to 40% for N-butyl-cyanoacrylate, and the 5-year recurrence rate with ALTA was reported at 18.2%. Comparatively, the recurrence rates at 12 months for the general population, when employing polidocanol foam sclerotherapy, vary between 12% [21] and 16% [22], depending on the studied population. This rate does not differ significantly from the documented with the EAO agent in cirrhotic patients. Regarding safety outcomes, the most reported issues include bleeding, ulceration, pain, and ascites. Overall, EAO appears to be associated with fewer adverse events compared to N-butyl-cyanoacrylate, with both agents having similar rates of abscesses and hematocyst formation. However, EAO is linked to higher pain levels and a higher need for analgesia, leading to lower satisfaction rates. On the other hand, ALTA sclerotherapy carries a higher bleeding risk than EAO but lower than N-butyl-cyanoacrylate.

IS emerges as an effective approach for treating hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patients, demonstrating recurrence rates comparable to the general population, although with a low patient satisfaction rate of 36.6% [11]. The sclerosing agent must be carefully chosen with EAO being associated with less adverse events, but higher pain levels, N-butyl-cyanoacrylate with higher satisfaction rates but increased recurrence rates, and ALTA with ascites as a potential adverse event. Although the pathophysiological mechanism is not certain, ascites following ALTA treatment might happen due to the inflammatory response that originates after the injection of a sclerosing agent, with a subsequent increased capillary permeability in a susceptible population.

Comparing RBL and IS performed in the cirrhotic population, both techniques demonstrated effectiveness and exhibited similar adverse event rates. However, pa-tient satisfaction rates were higher with RBL, likely attributed to the reduced associated pain [11].

The emborrhoid technique showed a clinical improvement rate of 80% with a reported bleeding relapse of 40%. No major adverse events were documented. However, these findings appear less promising compared with those previously published for generic patients with high surgical risk. In those, a clinical improvement rate of 100% was reported and a recurrence rate and an adverse event rate of, respectively, 14.3% for each were reported [23].

Regarding surgical treatment modalities, namely stapled hemorrhoidopexy, the reviewed studies highlighted this technique as an attractive method for managing HD in cirrhotic patients, due to its relatively brief mean operation duration, short hospitalization period, and reduced time to return to daily activities. Adverse events include post-procedural bleeding, manageable with the application of biological glue (reducing to 0% vs. 25%without glue application), pain (with mean VAS scores ranging from 5.5 at 6 h postoperative to 0.8 at 21 days postoperative), fecal impaction (62.5%), dysuria (25%), and urinary retention needing catheterization (37.5%). Comparing to the general population, bleeding rates are similar (from 0% to 68% in non-cirrhotic population)[24], while rates of fecal impaction (from 1.9% to 6%)[25-29] and urinary retention (from 0 to 22%) [24] are higher.

While it appears to be a favorable method with high patient acceptability (62.5% with good satisfaction), there is symptomatic recurrence at 4 months, in line with the high recurrence rates reported for the general population. This aligns with the general population’s high recurrence rates reported in previous studies [30].

This review has some limitations that we should underscore: first, the restricted pool of included studies, which emphasizes the paucity of research on this subject; second, the design of the included articles, with one single RCT assessed with a high risk of bias. Most of the remaining studies are single-arm investigations, valued primarily for their role in hypothesis generation and initial insights, yet generally regarded as weaker in evidence. Furthermore, the heterogeneity observed in both pre-procedural and post-procedural medical therapy, as well as the lack of a standard definition for each in outcome, precluded a comprehensive comparison of techniques. Finally, it is important to refer a major limitation in interpreting and comparing data when directly comparing percentages from different studies, particularly those using different therapies and with small sample sizes (e.g., Komporozos et al. [15] and Miyamoto et al. [14] studies), as this can lead to variability and weak statistical power.

Despite the mentioned drawbacks, this review represents a valuable and pioneering work in this field, aiming to fill the gap in the preexisting literature by thoroughly investigating the efficacy and safety of the available treatment modalities for HD in liver cirrhotic patients. These findings can lead to clinical practice change, as they challenge previous assumptions. Namely, those outlined in guidelines [31-33], regarding the feasibility of some office-based or surgical interventions in cirrhotic patients, such as the perception that RBL was unsuitable for cirrhotic population. Thus, this comprehensive systematic review allows to set up a fundamental framework of evidence-based medicine and provides rationale for future research.

Conclusion

All treatment methods assessed in the included studies appear to be effective and safe for use in patient with liver cirrhosis, although with variations in success rates and adverse event profiles. This challenges previous assumptions, consequently reshaping the paradigm concerning HD management in cirrhotic patients.

Future studies must focus on RCT to thoroughly assess the efficacy and safety of managing HD in cirrhotic patients. Incorporating newer and promising treatment modalities, such as polidocanol foam sclerotherapy, a minimally invasive technique that has already proven to be more effective than RBL in the general population and at least as effective and safe in patients with bleeding disorders, is an imperative research demand in this setting.