Introduction

Aortoesophageal fistula (AEF) is a rare but catastrophic cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding that occurs due to an abnormal communication between the aorta and the esophagus [1, 2]. The diagnosis should be suspected when upper GI bleeding occurs in the context of aortic disease, since the main etiology is secondary to aortic interventions, followed by native aortic aneurysm [2, 3]. Diagnosis is made based on clinical findings, upper endoscopy, and computed tomography angiography (CTA) [4-6]. The authors describe a rare case of an elderly patient who presented with intermittent bleeding and endoscopic findings suspicious of Dieulafoy disease, which were subsequently identified as an AEF.

Case Report

An 86-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to melena and hematemesis with hemodynamic instability. His medical history includes arterial hypertension, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and prostate cancer under surveillance. The patient had a hospitalization 2 months prior for an ischemic cardioembolic stroke complicated by hematemesis of unknown etiology after initiation of anti-coagulation, which prompted its cessation. He was discharged home on aspirin. After hospitalization, there were several visits to the ED due to melena, hematemesis, and symptoms related to anemia, requiring red blood cell transfusions and multiple upper endoscopies showing blood in the gastric lumen or no abnormal findings. Chronic medication also included bisoprolol, amlodipine, metformin, sitagliptin, esomeprazole, enzalutamide, and goserelin. He denied intake of alcohol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

On admission, the patient was hypotensive, pale, and had cold extremities. His hemoglobin was measured at 6.1 g/dL; the remaining blood count was normal. There were no alterations in renal function, liver profile, and coagulation. He had hyperlactatemia (4.9 mmol/L) and troponin elevation (446 pg/mL) without chest pain or ischemic electrocardiographic changes. He received two units of packed red blood cells, fluid resuscitation, and intravenous esomeprazole, leading to hemodynamic stabilization in the ED. Upper endoscopy revealed a giant non-mobilizable clot in the gastric fundus, with no hemorrhagic lesions found throughout the exam. An abdominal CT angiogram showed no evidence of active GI bleeding. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit, and next-day reassessment esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was normal. He remained clinically stable and without visible blood loss.

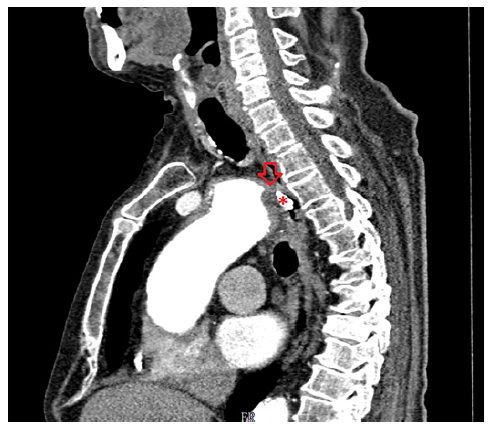

On the eighth day of hospitalization, the patient was readmitted to the intensive care unit in hemorrhagic shock due to new-onset hematemesis. He was intubated and treated with aggressive resuscitation and transfusion of red blood cells. EGD revealed an esophageal 10-mm non-ulcerated mucosal depression with a visible vessel at 20 cm from the incisors (shown in Fig. 1), closed with 3 hemoclips. Thoracic CT angiography showed a brachiocephalic trunk aneurysm with aortoesophageal fistulization (shown in Fig. 2). The vascular surgery department at our hospital and the cardiothoracic surgery department at a tertiary center were consulted, but the patient was deemed unsuitable for endovascular or surgical treatment given the anatomical characteristics of the fistula and his general condition. He subsequently recovered and was able to be discharged home. About 2 months later, the patient was admitted to the emergency room in cardiorespiratory arrest following an episode of hematemesis at home.

Discussion

An AEF is an uncommon and potentially fatal cause of upper GI bleeding. As the name suggests, this condition arises from an abnormal communication between the aorta and esophagus, which allows high-pressure arterial blood to enter the esophagus [1, 2]. The middle portion of the esophagus is the most common site for aortoesophageal fistulization [3, 7]. This disease should be considered in patients who have a history of aortic intervention since most cases are secondary to vascular procedures. It can also originate from the native aorta, arising from thoracic aortic aneurysms, as in our patient, but also after ingestion of foreign bodies, or from tumor invasion [2, 3].

Although the first case of AEF was reported in 1818, the classic triad of symptoms was described by Chiari almost a hundred years later [8]. Patients may experience midthoracic pain, sentinel arterial hemorrhage, followed by a symptom-free interval, and finally a massive bleeding [7-9]. In a minority of cases, bleeding is intermittent, presumably due to the formation of a blood clot that temporarily seals the opening of the fistula [9, 10]. Our patient did not have known risk factors for the disease, such as previous aortic intervention, and presented with less typical symptoms, which may have contributed to a low index of clinical suspicion.

EGD plays an important role in the evaluation of upper GI bleeding; however, its sensitivity for AEF diagnosis is low. The diagnosis can easily go unnoticed in endoscopy if there is no active bleeding and because the typical endoscopic findings, such as submucosal tumor-like protrusion or pulsating arterial bleeding, are rarely found [3, 4, 10].

CTA is recommended as a first-line noninvasive examination in the suspicion of AEF and is diagnostic in most cases [4, 6]. In our case, the findings on EGD associated to intermittent bleeding raised the hypothesis of Dieulafoy lesion, which was not confirmed by CTA. In fact, the CTA was essential to establish the definitive diagnosis of AEF, as the clinical history and endoscopy findings were not suggestive. We emphasize the significance of performing a thoracoabdominal CTA when investigating the etiology of upper digestive bleeding. This is highlighted by the fact that the initial CTA was abdominal and unremarkable, while the subsequent thoracic CTA revealed the final diagnosis.

The management of AEF should involve a multidisciplinary approach and a therapeutic strategy individualized with consideration of both esophageal and aortic defects. A combination of surgery for the aorta (endovascular or open surgical repair) and esophagus (esophagectomy, esophageal stent, or repair) is usually adopted [2, 11]. In cases where correction of the aorta is not possible, as in our patient, the endoscopic treatment aims to palliate new episodes of bleeding, since the aortic defect and fistulous tract remain intact. The literature is scarce regarding the positioning of the different endoscopic interventions for palliation probably because cases of successful vascular treatment appear overwhelmingly more likely to be reported than cases of unfavorable clinical outcomes. Our therapeutic approach was chosen based on the location (20 cm of the incisors), the probable cause (Dieulafoy’s lesion), as well as the difficult access and stabilization of the endoscope that precluded other therapeutic options. We considered that a subsequent change in the endoscopic therapeutic strategy could precipitate a new episode of bleeding, and none of the endoscopic options allows definitive treatment of AEF.

Perhaps there may be a role for combining other endoscopic techniques in cases similar to ours, with only an indication for endoscopic treatment, such as the injection of sclerosants or tissue adhesives, if the diagnosis of AEF is known from the beginning.

In conclusion, the case highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic complexity of AEF. A low threshold for performing a CTA is recommended, particularly when there are frequent symptoms of upper digestive bleeding and clear signs observed during endoscopy. Endoscopic treatment not only allows hemostasis in the episode of acute bleeding but also may become the main therapy of AEF in patients without indication for vascular intervention for palliation of new bleeding episodes.