Introduction

A pelvic abscess is a life-threatening condition that might occur either as a complication of an abdominopelvic surgical procedure or spontaneously as a consequence of an underlying medical condition, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, diverticulitis, appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, sexually transmitted diseases [1-3].

Abscess management has evolved considerably over time from surgery to minimally invasive techniques. Pelvic abscesses should be managed conservatively with antibiotic treatment when possible. However, due to the thickness of the abscess wall, antibiotic treatment often fails to reach appropriate concentrations within pelvic fluid collections (PFCs). Therefore, drainage should be considered for individuals who present with abscesses larger than 3 cm or in the presence of sepsis [2]. PFCs are routinely drained surgically or via computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound (US)-guided procedures [4]. CT-guided percutaneous drainage may be performed through a transabdominal or transgluteal route [1], which requires a catheter placement that may need to remain in situ for weeks or months. This is not only uncomfortable and potentially painful but is also associated with an increased risk of fluid and electrolyte loss, catheter dislodgement and cutaneous fistula formation [1, 5]. Nowadays, surgery is usually reserved for patients with perforation or those unresponsive to minimally invasive CT or US-guided drainage procedures [1].

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided pelvic abscess drainage offers an alternative to CT and US-guided percutaneous and transanal drainage procedures. This method was first described in 2003 as a minimally invasive alternative for PFCs located adjacent to the rectum and left colon [6].

The use of lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMSs) was first reported in 2011 [7]. LAMSs were originally developed for the management of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections, such as pancreatic pseudocysts and walled-off necrosis [5, 7-9]. However, novel off-label indications for their use include the management of gallbladder and bile duct drainage, gastrointestinal strictures, creation of gastrointestinal and enteroenteric anastomoses, management of patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy and drainage of intra-abdominal and pelvic abscesses [5, 9]. EUS-guided drainage with LAMS has been shown to be a minimally invasive, efficient and safe alternative treatment for pelvic abscesses [3, 4], especially for those collections less than 1 cm from the gastrointestinal lumen and more than 6-8cmfromthe anal verge[8].Furthermore, it avoids the complications associated with percutaneous drainage and has been proven to improve the quality of life [5].

Methods

We conducted an observational retrospective study involving 6 patients referred to our hospital for EUS drainage after a PFC was identified on cross-sectional imaging studies. The PFCs were deemed too large for conservative antibiotic therapy and were associated with septic complications. Due to their location, they were not considered manageable by percutaneous drainage and surgery was avoided due to patients’ comorbidities and the aim to prevent increased morbidity and mortality associated with a more invasive surgical procedure. Patient records were reviewed to identify the etiology, size of the collection, number of endoscopic procedures required until complete PFC resolution, stent indwelling time, concomitant surgical or percutaneous associated procedures, successful LAMS removal and PFC resolution.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the procedure. All procedures were performed under anesthesiologist-monitored deep sedation and by the same experienced interventional endoscopist using a lineararray PENTAX® echoendoscope and a Hitachi HI VISION Preirus ultrasound platform.

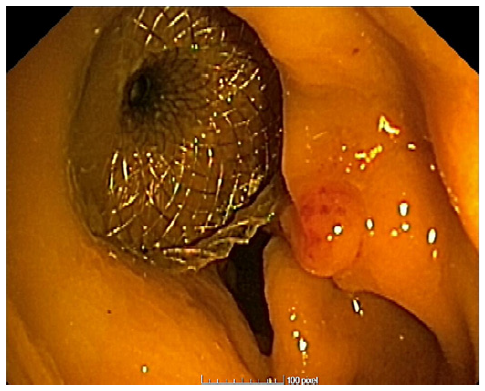

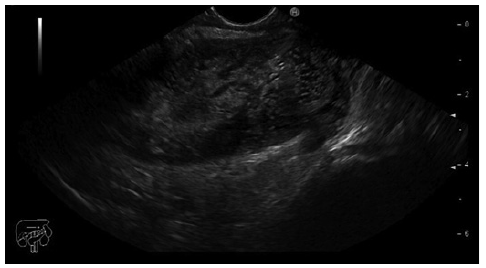

Prior to the puncture, the PFC was carefully evaluated for size and location, ensuring the collection was within 1 cm from the rectosigmoid wall and that no intervening blood vessels would impede the procedure. An electrocautery-enhanced LAMS delivery system (Hot-Axios®; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) with a stent diameter of 15 or 20 mm was used based on the endoscopist’s discretion and availability at the time of the procedure. The ERBE VIO 200D electrosurgical unit, using AUTOCUT mode, effect 5, power 100 W, was employed for the transrectal puncture with the Hot-Axios® system. The direct puncture technique was performed under EUS guidance alone (without fluoroscopic assistance). The distal phalanx deployment was executed under ultrasound visualization, while the proximal phalanx release was conducted with endoscopic or/and ultrasound view (Fig. 1, 2).

The primary endpoint was clinical success, defined by successful LAMS deployment followed by PFC resolution based on endoscopic evaluation, clinical and biochemical improvement and no need for additional drainage intervention. Secondary endpoints included adverse events; reintervention; PFC recurrence and need for surgery.

Given the limited literature regarding this use for LAMS, the collection was evaluated endoscopically during follow-up. The decision to remove LAMS was based on evidence of a residual collection covered by granulation tissue without purulent drainage, alongside evident clinical and biochemical improvement. LAMS removal was performed using alligator foreign body forceps with a 2.3 mm diameter and 230 cm working length, with spontaneous tract closure and complete abscess resolution confirmed via a follow-up CT scan. The time of follow-up varied according to the case. A descriptive analysis of the results was conducted.

Results

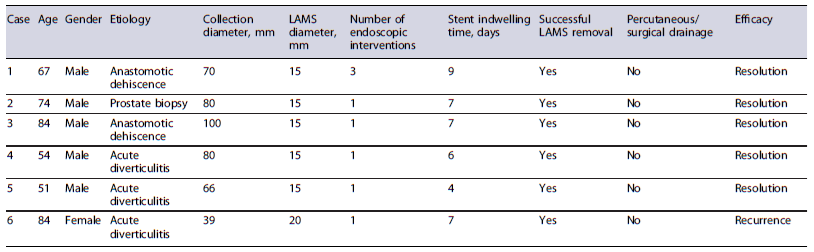

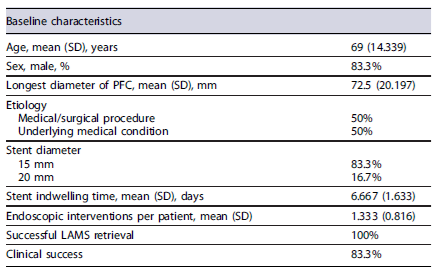

The characteristics of individual cases are shown in Table 1, while the sample’s baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Six patients were included in this study, five of whom were male, with ages between 51 and 84 years (average age of 69 years).

Regarding the etiology of the PFCs, three cases were related to acute diverticulitis, two were due to anastomotic dehiscence and one case followed a prostate biopsy (Fig. 3). The size of the PFCs rangedfrom 39 to100 mm.

In all cases, a 15 mm stent diameter was used, except in one case where a 20 mm stent diameter was utilized. Only the first procedure performed at our department required more than one endoscopic session prior to stent removal for cleansing, washing and debris removal. All other stents were removed during the subsequent endoscopic reevaluation. The stent indwelling time ranged from 4 to 9 days, with the first case having the longest duration.

No patients required additional percutaneous or surgical drainage procedures for PFC resolution. However, 1 patient (16.7%) underwent a diversion colostomy following LAMS placement to expedite the clinical resolution of a concomitant Fournier’s gangrene.

All patients (100%) experienced successful PFC drainage following LAMS placement. Nonetheless, 1 patient (16.7%) had an immediate recurrence (less than a week) after LAMS removal. This same patient not only had a recurrence at the original site but also developed a new PFC in a different location related to complicated acute diverticulitis. As both PFCs were smaller than 3 cm no reintervention was performed and the patient was considered unsuitable for surgery due to concomitant comorbidities. No adverse events related to LAMS placement were reported during the follow-up period.

Discussion

Our six-case study suggests that EUS-guided drainage with LAMS is an effective and relatively safe treatment option for PFCs. The large stent diameter facilitates rapid drainage, enables endoscopic access for cleansing and direct evaluation of the collection, and minimizes the risk of stent obstruction. Additionally, the dumbbell shape of LAMS reduces the risk of migration. Given the limited literature on the use of LAMS for PFCs, we propose that endoscopic evaluation might suffice for fluid collections without necrotic tissue, as observed in our study. However, radiological follow-up may be necessary for more complex collections. Spontaneous tract closure after stent removal can be confirmed via follow-up CT scans.

Several particularities of our study merit consideration. The first case performed at our institution required more endoscopic procedures and a longer stent indwelling time, which can only be partially attributed to the PFC characteristics. However, this was also likely influenced by thefactthat itwas the first procedure performed at our institution, with the endoscopist exercising extra caution regarding PFC resolution before stent removal.

Another noteworthy case involved a female patient with a 39-mm PFC. Early recurrence in this case was likely due to a complicated acute diverticulitis. This patient had a history of multiple episodes of acute diverticulitis, with the current episode complicated by a pelvic abscess unmanageable by percutaneous drainage due to its location. Antibiotics were ineffective and the patient was not a candidate for surgery. EUS-guided drainage was considered the last resort for PFC resolu-tion. Consistent with the existing literature, patients with diverticulitis pose significant challenges due to the extent and recurrent nature of the disease. These patients are also more prone to procedure-related complications, such as perforation. As with all endoscopic procedures, patient selection is critical.

While CT/US-guided percutaneous drainage remains the gold standard approach for managing pelvic abscesses, EUS-guided LAMS drainage has proven to be more efficient and safer compared to other methods [3, 7]. The wider diameter allows for transmural drainage and direct passage of the endoscope through the stent for inspection and debridement. However, its placement is not devoid of complications, such as stent obstruction, stent migration and bleeding. The larger diameter reduces the risk of obstruction and the dumbbell shape minimizes the risk of migration compared to plastic stents [9, 10]. The use of LAMSs should be considered in immuno-compromised patients, when percutaneous drainage is technically challenging or when surgical drainage is not feasible [8].

Conclusions

EUS-guided drainage of PFCs with LAMSs is a safe and minimally invasive technique that allows rapid PFC resolution without the need for percutaneous or surgical drainage interventions. However, since our study did not include a comparative analysis with other methods (percutaneous or surgical), no comparative results can be drawn. Additionally, a formal quality-of-life assessment was not performed, so we cannot make conclusions about quality-of-life parameters. Further and larger prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings and to evaluate the impact on quality of life, hospitalization time and cost-effectiveness.