Introduction

Gastric pathologies, including gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, are frequently encountered in clinical practice, with well-established causes such as Hp infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. However, there is growing recognition of drug-induced gastrointestinal diseases related to medications not traditionally associated with such effects, including angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB). ARBs are a widely used class of antihypertensives known for their cardiovascular benefits, but recent reports have high-lighted potential links between their use and gastrointestinal complications.

Olmesartan, a commonly prescribed ARB, has been implicated in causing conditions such as enteropathy and gastropathy. The clinical presentation of ARB-induced gastropathy can be subtle and nonspecific, often delaying diagnosis. Symptoms may persist despite conventional treatment for gastritis or peptic ulcers, and standard etiological investigations, including Hp testing, may be negative. In such cases, medication-related causes should be considered.

Case Presentation

An 85-year-old man with arterial hypertension, treated with olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide for the past 12 years, presented to the emergency department with epigastric pain that had developed gradually over several months. He reported no associated symptoms such as vomiting, blood loss, diarrhea, or weight loss. There was no history of NSAID use, and he had no family history of gastric cancer.

Physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory studies and computed tomography revealed no changes. The patient’sfamilydoctorhadpreviously ordered an UGE, which showed congested mucosa in the distal body, gastric notch, and antrum, with a firm consistency, irregular erosions, and friable areas that appeared suspicious. There were no other findings of note. The patient was treated with lansoprazole and sucralfate. Histology showed severe intestinal metaplasia with low-grade dysplasia in the gastric antrum, chronic gastritis with moderate inflammation, and severe atrophy. No signs of Hp or granulomas were found. He was discharged with twice-daily 40 mg esomeprazole, and a gastroenterology consultation was requested.

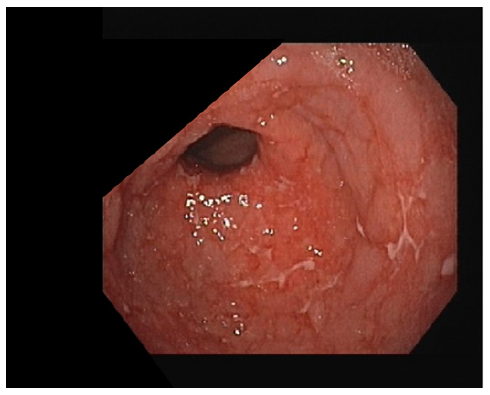

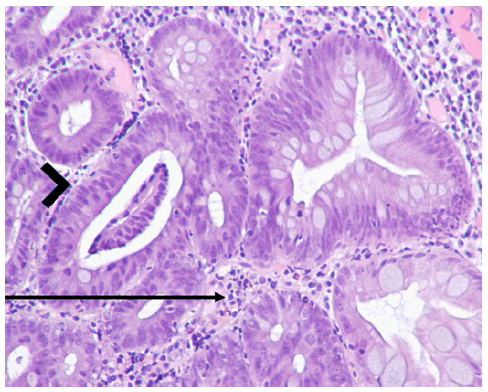

Three months later, a follow-up UGE showed per-sistent erosions and ulcers in the gastric antrum (shown in Fig. 1), despite good adherence to esomeprazole. Histology revealed moderate chronic gastritis with severe inflammation and abundant eosinophils (20 eosinophils per high power field), severe intestinal metaplasia with low-grade dysplasia, and marked atrophy (shown in Fig. 2). No granulomas, giant cells, or signs of malignancy were found, and Hp was not detected. Hp serology was performed, and it was positive, so quadruple therapy with bismuth was prescribed. Post-eradication urea breath test was negative.

Fig. 2 Histopathological findings of gastric mucosa prior to discontinuing olmesartan, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), at ×100 magnification. Inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria (arrow), indicative of gastritis, and low-grade dysplasia (arrowhead) were present.

Six months later, a repeat UGE still showed multiple superficial ulcers in the distal body and antrum. Histology revealed diffuse chronic gastritis without active inflammation, along with intestinal metaplasia, but no dysplasia, giant cells, or granulomas. At this point, the possibility of olmesartan-induced gastropathy was considered, and olmesartan was replaced with lisinopril.

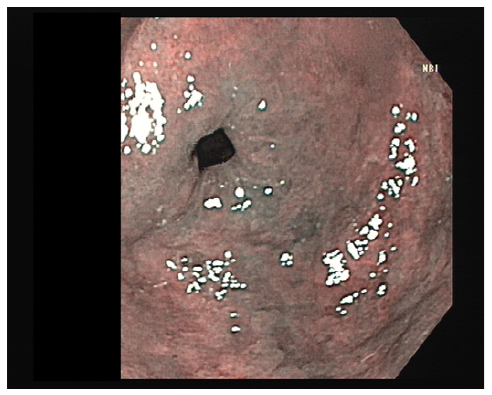

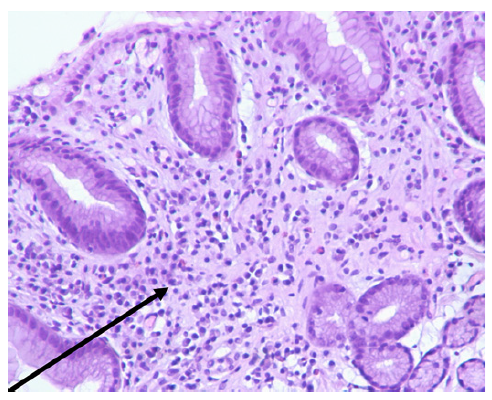

Another UGE, performed 6 months after changing antihypertensive therapy, showed areas of atrophy and metaplasia in the antrum and notch but no ulcers or erosions (shown in Fig. 3). Biopsies demonstrated a reduction in inflammatory infiltrate and an absence of dysplasia, indicating histological improvement (shown in Fig. 4). Olmesartan-induced gastropathy was assumed to be the cause of the initial symptoms.

Fig. 3 Gastric antrum visualized using narrow band imaging (NBI) during upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, after stopping olmesartan.

Fig. 4 Histopathological findings of gastric mucosa after discontinuation of olmesartan, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), at ×100 magnification. A reduction in the inflammatory infiltrate (arrow) was observed, indicating histological improvement.

Duodenal biopsies were not performed as there was no clinical suspicion of malabsorption syndrome. The patient’s condition improved following the change in antihypertensive therapy, with a resolution of symptoms

and stabilization of gastric histopathology.

Discussion

This case involved an 85-year-old man with a 12-year history of olmesartan/hydrochlorothiazide therapy for hypertension, who presented with progressive epigastric pain over several months. Despite treatment with proton pump inhibitor and successful eradication of Hp infection, UGE revealed persistent gastric erosions and ulcers. Histological findings included severe chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and abundant eosinophilic infiltration. After olmesartan was discontinued and replaced with lisinopril, follow-up endoscopy and histology showed significant improvement, with resolution of ulcers and reduced inflammation. This suggested that olmesartan-induced gastropathy was a probable diagnosis, although it remained non-definitive, as there are no pathognomonic features specific to this condition.

In this case, the differential diagnosis of refractory peptic ulcer disease must consider several possibilities. Initially, Hp infection was a likely cause, especially given the patient’s histological findings of chronic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Although the initial biopsies were negative for Hp, the positive serology warranted a trial of eradication therapy. Post-eradication urea breath test confirmed successful Hp eradication. Despite this, the persistence of ulcers on follow-up endoscopy suggested a non-Hp-related cause of the refractory disease. The absence of NSAID use ruled out one of the most common causes of drug-induced peptic ulcers. Other less common conditions that could be considered include Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, although this was unlikely given the absence of significant weight loss or diarrhea. Autoimmune gastritis was also considered in the differential diagnosis; however, it typically affects the gastric body, where parietal cells and intrinsic factor are produced, rather than the antrum, which appears to be the predominant site of gastritis in this case. Crohn’s disease was another possibility, but there were no accompanying symptoms such as diarrhea, and multiple biopsies revealed no typical pathology findings. The resolution of the patient’s ulcers following the discontinuation of ol-mesartan strongly supports olmesartan-induced gastro-pathy as the most likely diagnosis.

ARBs are a pharmacological class widely used as antihypertensive therapy. By inhibiting angiotensin II activity in type 1 angiotensin receptors, ARBs decrease vasoconstriction and aldosterone production and con-sequently reduce blood pressure. Recently, a relationship between these agents and gastrointestinal disease has been described, namely, enteropathy, gastropathy, and microscopic colitis [1, 2].

The most common symptoms associated with the disease are abdominal pain, weight loss, and diarrhea [3]. However, weight loss and diarrhea are likely more closely related to ARB enteropathy, given the high cooccurrence of both conditions. That said, some patients with probable ARB gastropathy and normal duodenal histology have also experienced weight loss [3].

Few studies have been conducted on the gastric involvement of ARB. The most common endoscopic findings in the stomach are nonspecific and include er-ythema, mucosal nodularity, friability, and erosions/ulcers, both in the antrum and on the body [3]. Histological findings are often heterogeneous and nonspecific, including lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with eosinophils, as seen in this case, and other features such as glandular atrophy, occasional intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial lymphocytes, subepithelial collagen deposition, and epithelial surface lesions [1, 3]. These findings may involve the entire mucosa or the intermediate region (unlike Hp gastritis, where inflammation predominantly affects the surface of the mucosa). The presence of dysplasia has not been reported in other cases of ARB-induced gastropathy in the literature.

Olmesartan is the most frequently involved ARB [3], but there are also cases described with telmisartan and irbesartan. The mechanism is unknown, but it is thought that a cell-mediated immune reaction is involved and does not appear to be a class effect [3]. There may be gastric disease without duodenal disease [3, 4], but the co-occurrence of both varies between 15 and 50% [3]. The latency period between the initiation of the drug and the onset of symptoms can range from 6 months, as reported in the literature [3], to several years, as observed in this case. For other ARB-related conditions, such as enteropathy, the time between starting ARB treatment and the onset of symptoms can also span several years [3, 5]. Symptoms are variable with weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting being the most common. Treatment consists of stopping the drug and rechallenge can confirm the diagnosis.

It is important to note that the initial two UGE did not report clear margins for any lesions, and the severity of the endoscopic findings appeared inconsistent with low-grade dysplasia. This raised the possibility that the findings could have been a misinterpretation of severe inflammation or as a sampling error indicative of diffuse gastric cancer. Consequently, a strategy of close surveillance was adopted, considering both low-grade dysplasia and diffuse gastric cancer as potential diagnoses.

In this specific case, the observed low-grade dysplasia could have been associated with a concurrent inflammatory process resulting from a long-standing chronic Hp infection. Furthermore, distinguishing between low-grade dysplasia and inflammation can be particularly challenging in the context of severe inflammation, especially given that only one pathologist examined the histological results in this instance.

Importantly, the UGE conducted after the discontinuation of olmesartan revealed improvements in the endoscopic appearance of the gastric mucosa, alongside a reduction in histological inflammation and no evidence of dysplasia. This strongly suggests that the initial findings were likely misinterpreted as inflammatory changes. This case emphasizes the need for heightened clinical awareness of drug-induced gastrointestinal disorders, particularly when standard treatments fail to resolve symptoms, and highlights the importance of considering ARB-related gastropathy as part of the differential diagnosis.