Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Portuguese Journal of Public Health

versão impressa ISSN 2504-3137versão On-line ISSN 2504-3145

Port J Public Health vol.37 no.2-3 Lisboa 2019

https://doi.org/10.1159/000506261

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Expanding Primary Care to Pharmaceutical Patient Care in Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 through the European Union’s Community Pharmacies, between 2008 and 2018: A Systematic Review

Expandindo os cuidados de saúde para os cuidados farmacêuticos na diabetes mellitus tipo 2 através das farmácias comunitárias da União Europeia, entre 2008 e 2018: Revisão Sistemática

Ângela Maria Vilaça Pereira de Araújo Pizarro a, b Maria Rosário O. Martins a, b Jorge Almeida Simões a, b

a Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, International Public Health and Biostatistics Unit, New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal;

b Global Health and Tropical Medicine, Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, International Public Health and Biostatistics Unit, New University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

ABSTRACT

Background: The analysis of the European Union (EU28) health systems’ intervention for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) reports an insufficient combination of legal support, prevention, and early diagnosis. This fact compromises the patient’s health outcomes. The inclusion of pharmacy services oriented to T2DM (PS-T2DM) in strategic primary care network’s programs could be a solution. However, the different regulatory frameworks that include good pharmaceutical practices and clinical guidelines for T2DM in each EU28 country may be a limitation. Health systems need to know the evolution of these community services and to analyze their operational and regulatory base, both in time and space. - Methods: A systematic review was carried out on a qualitative and quantitative approach to the expansion and upgrading of PS-T2DM provided in EU28 pharmacies between 2008 and 2018. - Results: The implementation of PS-T2DM in EU28 has increased sharply since 2009 and 2010. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is regulated in 5 countries (Bulgaria, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, and Portugal) and T2DM in 3 (Austria, Latvia, and Romania). Also, in 3 countries (Latvia, Poland, and Spain), pharmacists are involved in implementing guidelines for DM and T2DM, but there is no evidence on the regulation of PS-T2DM. Twenty-two countries showed detailed studies for the PS-T2DM’s provision. The type of PS-T2DM implemented in the highest number of EU28 countries was “promoting the rational use of medicines,” and the specific subtype T2DM-related more commonly reported was the “glucose measurement.” - Discussion/Conclusion: Pharmacy disease-oriented services contributed to improving the accessibility, proximity, and equity of primary care for T2DM provided in community pharmacies across the EU28 in recent decades. This promising strategy for improving health outcome sets may be a call to the action of health systems due to its impact consistent with some objectives of universal health coverage for the eradication of DM and T2DM.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus type 2 Community pharmacy services Outcome sets monitoring European Union

RESUMO

Introdução: A análise da intervenção dos sistemas de saúde da União Europeia (UE28) para a diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (T2DM) relata uma combinação insuficiente em termos de apoio jurídico, prevenção e diagnóstico precoce da doença, o que compromete os resultados de saúde. A inclusão de serviços de cuidados farmacêuticos orientados para a T2DM (PS-T2DM) nos programas estratégicos da rede de cuidados de saúde primários pode ser uma solução. No entanto, a diferente estrutura reguladora, que inclui as boas práticas farmacêuticas e as diretrizes clínicas para T2DM de cada país da UE28 podem ser uma limitação. Os sistemas de saúde devem conhecer a evolução conjunta desses serviços e analisar a sua base operacional e regulatória, tanto no tempo quanto no espaço. Métodos: Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática, numa abordagem qualitativa e quantitativa, da expansão e atualização da prestação de PS-T2DM nas farmácias comunitárias da UE28 entre 2008 e 2018. Resultados: Houve um aumento do número e tipo de PS-T2DM na UE28 desde 2009-2010. A diabetes mellitus (DM) encontra-se regulada em 5 países (Bulgária, Espanha, Itália, Lituânia e Portugal) e a T2DM em 3 (Áustria, Letônia e Romênia). Além disso, em 3 países (Letônia, Polônia e Espanha) os farmacêuticos estão envolvidos na implementação das guidelines para a DM e T2DM, embora não haja evidências sobre a regulamentação dos PS-T2DM. Vinte e dois países mostraram estudos concretos para a prestação de PST2DM. O tipo de PS-T2DM implementado num maior número de países da UE28 foi “promoção do uso racional de medicamentos” e o subtipo específico para a T2DM mais comumente relatado foi a “medição de glicose”. Discussão / Conclusão: A crescente contribuição para a melhoria da acessibilidade, proximidade e equidade dos cuidados primários para T2DM prestados em farmácias comunitárias em toda a UE28 nas últimas décadas deve-se à disponibilidade crescente de serviços orientados para a doença. Essa estratégia promissora do melhoramento dos resultados de saúde mostrou a possibilidade de ter um impacto positivo e consistente com alguns objetivos da cobertura universal de saúde para a erradicação da DM e da T2DM, assim como atuar como um apelo à ação dos sistemas de saúde.

Palavras Chave: Diabetes mellitus tipo 2 · Cuidados farmacêuticos · Monitorização dos resultados de saúde · União Europeia

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus(DM) is a complex heterogeneous metabolic disorder considered to be one of the world’s worst noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) 1 ,2 . DM was the leading cause of hospitalization in the European Union (EU) in 2015. Current global data estimates that there are around 463 million adults with DM (2019), and it will increase to 700 million in 2045 (20–79 years old) 2 ,3 . Also, around 232 million cases of DM are undiagnosed, and the annual global expenditure on DM is estimated at 760 billion – regarding its treatment and prevention of complications, around 150 billion EUR were spent in total and about 4.6 billion EUR per adult/year 2 -5 . The most heterogeneous and common type of DM is the “type 2” (T2DM), which corresponds to about 90% of DM cases worldwide 2. It is characterized to manifest chronic hyperglycemia that can damage blood vessels and nerves, causing long-term irreversible complications that represent >50% of the mortality in people with T2DM 6 ,7 . Also, the other disorder closely related to DM is “prediabetes” which signifies a risk of the future development of T2DM and its complications. This is a term increasingly used to designate the impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) and the impaired fasting glucose (IFG) 2 ,3 . In order to respond to the DM burden’s grow in a global health perspective, world health systems have been working together over the last decades, expressing common concerns about DM eradication and seeking to implement effective interventions to reduce its impact, mainly on the economic and social level 4 ,5 , 8 - 11 . In 2008, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed an action plan focused on reducing the global burden of 4 chronic diseases that included DM 10 ,12 ,13 and its latest report – the WHO Global Report on DM (2016) – declared that DM should be included in all NCD’s policies 13. In parallel, some of the most influential international health entities and pharmaceutical sciences organizations from most EU countries (International Federation of Pharmacists, Pharmaceutical Group of European Union [PGEU], Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe, professional associations, and pharmacy associations) have taken joint initiatives to make the community pharmacy and the pharmaceutical care practitioners (the community pharmacist, CPH) more collaborative with primary care and involved in its networks and projects, beyond the dispensing of medicines to the community (started in 1950) and the practice of handling pharmacy (started in 1910–1920). Thus, today, community pharmacy and CPH are centered on clinical pharmacy practice and primary care. CHP is focused on disease management, giving priority to making early diagnosis and pharmacovigilance. This kind of pharmaceutical patient care is realizedthrough services that are called“pharmacy services” (PS) 11 ,14 . The study aimed to explore evidence of implementing pharmaceutical care in T2DM in EU28 community pharmacies over 10 years (2008–2018). Besides, it sought to explore the diversity, complexity, and the existence of regulation for PS-T2DM.

Methods

The main objective of this study was to analyze the implementation of pharmaceutical care in T2DM in community pharmacies of EU28 countries, as pharmacy services, with the evidence available between 2008 and 2018. The research question was elaborated based on the methodology Participants, Interventions, Control, Outcomes, Study design 15, and it was as follows: What type of pharmacy services for T2DM has been implemented in EU28 community pharmacies between 2008 and 2018 and which guidelines were supporting this?

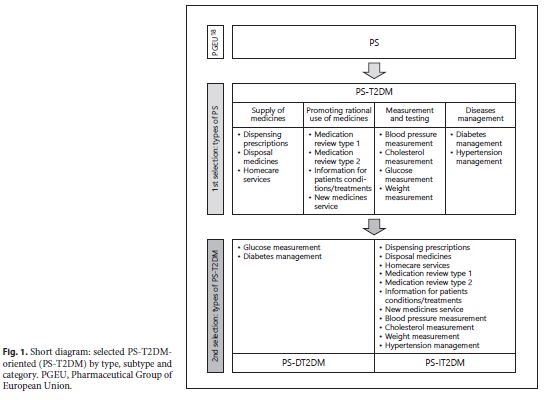

A systematic review of the literature was the research methodology selected because it is a precise and reliable way that allows synthesizing a substantive set of information with scientific evidence. Then, the Prisma statement ® methodology followed the elaboration instructions referred by Liberati et al. 16. According to the PGEU Annual Report 2010 17 and 2017 18, all types of PS (4) selected to be studied, and its subtypes (13) were summarized in figure 1 to organize the research and its results. The 4 types of PS were designated as “pharmacy services T2DM-oriented” (PS-T2DM) and divided into 2 categories. These categories are: (i) “pharmacy services directly oriented toward T2DM” (PS-DT2DM), which includes 2 PS subtypes: (a) glucose measurement , that consists of the measurement of plasma glucose levels and can be calculated either in fasting or in postprandial phase and (b) diabetes management, that consists of a pharmaceutical patient consultation to manage health status and monitoring health outcomes (T2DM or prediabetes); and “pharmacy services indirectly oriented towards T2DM” (PS-IT2DM), which includes the following 11 subtypes of PS related to DM’s treatment adherence and parameters monitoring, and the management of its risk factors: (a) dispensing prescriptions , that consists of checking the medication in terms of dose and dosage, frequency, form, treatment duration, and appropriated instruction for each patient; (b) disposal of medicines , that consists of a service for the safe disposal of expired or unused medicines; (c) hope care services/homecare services , that consists of a support for patients with chronic diseases in tertiary care, in their homes; (d) medication review type 1 , that consists of a mandatory dispensing process (checking the medication, dose and dosage, frequency, form, treatment duration, and appropriated instruction for each patient); (e) medication review type 2 , that consists of structured and private consultation between the pharmacist and patient, where the “medication review type 1” happens simultaneously with the verification of treatment adherence and the safe, effective, and rational use of medicines; (f) information to patients on conditions/treatments , whose information is related to the disease and the current treatment prescribed to patients; (g) new pharmacy service , also known as “new medicines service” that consists of a medication review specifically provided to patients starting a new medication which aims to support adherence in the first month(s) of treatment; (h) blood pressure measurement ; (i) weight measurement , which may or may not include comparison with height and it results in the calculation of “body mass index”; (j) cholesterol measurement , by standard measurement of total cholesterol; and (k) hypertension management , which consists of a pharmaceutical patient consultation to monitoring the blood pressure values obtained at rest, over time, of the person whose disease (arterial hypertension) was diagnosed previously 17 ,18 .

The identification of the relevant literature followed 2 ways. It was based on a search in the PubMed, Web of Science, B-On, Health Policy, The Lancet and IndeX databases (R1); and by Google Scholar, other official documents of health (national and international) repositories, pharmaceutical legislation, and health and statistical data (R2). The research descriptors were limited to the variables resulting from the research question referred to above, which was as follows: “pharmacy services” OR “pharmaceutical care,” “community pharmacy” OR other expressions associated with pharmaceutical sciences (community pharmacist OR pharmacy), DM (diabetes mellitus type 2 OR diabetes type 2 OR T2DM), pharmaceutical legislation (clinical guidelines/guidelines for pharmaceutical care for diabetes/DM/diabetes type 2/T2DM), health policies for DM (public health diabetes/DM/T2DM-related), protocols for the implementation of pharmaceutical care for diabetes/DM/T2DM management in community pharmacies, pharmaceutical care in community settings, European Union, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom.

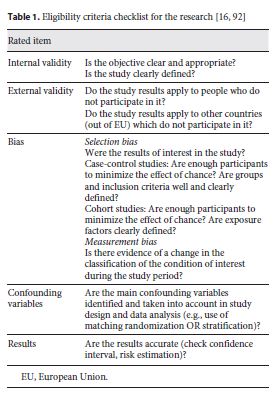

The search started exploring the PubMed database according to the Medical Subject Headings . The same strategy was subsequently done in other databases. Studies conducted in the last 12 years (period January 2008 – February 2020) were written in English, Portuguese, French, German, and Spanish. The selection of studies was made in 2 stages: screening and an evaluation of the quality of the studies. The screening was carried out through a checklist of the research question elaboration criteria – Intervention (exposure): pharmacy services for management of T2DM Control (group of): EU28 countries (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom); and Study design: ecological time-series study. Then, it was evaluated the quality of the studies also applying a PRISMA checklist 16 that met the eligibility criteria (table 1 , online suppl. Table S1; see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000506261 for all online suppl. material). Also, a validated tool (ROBIN-I, online suppl. Table S2) is used to assess some bias in the selected studies of the way research R1 could be seen on online supplementary Table S3.

“Introduction” and “Methods” were written with the support of the literature found between 2001 and 2020, to approach the theme from a temporal perspective. From the totality of the studies, the inclusion criteria were: empirical study reports referring to all interventions focused on the provision of PS to people with DM or T2DM, with available references, published in scientific and indexed databases; studies that included individuals aged 18 years or more; full-text articles with a clear theme and objective related to the research question. Exclusion criteria refer to studies with animals, not adults (<18 years old), specific studies for DM type 1 or gestational DM, studies related to other non-diabetes complications, studies not related to EU countries, studies inconclusive and lack of access to the full text of the studies. Studies that dealt with the subject but had variations, such as studies in a hospital/hospital pharmacy environment, were also excluded. The selection of the studies considered eligible included 2 stages: screening and non-categorical evaluation of study quality. In the first stage, the criteria for the elaboration of the research question were validated: participants/countries, interventions/community pharmacy and health systems, results and study design; in the second step, the full text of the articles considered relevant, using the same criteria, was analyzed to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the review. The total of documents collected was tracked following the 2 research paths mentioned above, R1 and R2. These studies were selected after repeated studies, and they were excluded in the 2 series (R1 and R2). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and read in full. The data collected were systematized in tables, which included all the most relevant elements of each study, namely: year, country, PS, PS-T2DM, PS-DT2DM, and PS-IT2DM, and guidelines and legal framework for DM/T2DM in each EU country, when available.

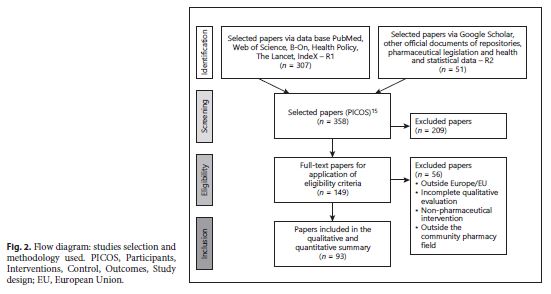

The analysis of the studies was predominantly interpretive and qualitative with a comparative approach. The final set of studies selected should describe pharmacy services not specific for T2DM, but applicable to T2DM and DM-related varying from country to country, and therefore differing in terms of social and demographic context, not considered as variables in the present study. A systematic review of the literature helped us to organize data/information found accurately, synthetically, and with evidence, because it was very dispersed either in R1 either in R2. figure 2 illustrates the dynamics of the identification and selection process of articles for analysis.

Results

Our study tracked 358 documents, 307 articles by R1, and 51 by R2. After a new selection, 93 articles were retained in total. This set was the study’s documentary core. Forty-nine studies related to the implementation of PS-T2DM in EU28, were selected and then organized in table 2 by country, by type, and subtype of PS-T2DM.

The PGEU Annual Report 2010 17 and PGEU Annual Report 2017 18 were the most noteworthy documents found by R2, in terms of results’ integrity, informative cooperation, and feasibility of data collection. Both documents classify pharmaceutical care as community pharmacy services. The PGEU Annual Report 2010 data supported the first phase of the research . In this document, it found 3 levels of pharmacy services’ classification: “core services,” “basic services,” and “advanced services.”The other reports (PGEU 2013– PGEU 2017) have the description and the categorization of pharmacy services, as it was mentioned in “Methods” 17 -22 . Besides, PGEU recognizes the CPH as the responsible person for the implementation and provision of all these community pharmacy services, as through patient counseling and dispensing medicines and health products (including or not in prescriptions) as pharmacovigilance and referral people with health conditions/diseases to the general practitioner (GP). It was also reported the benefits of a set of PS for disease management to improve health outcomes and the expansion in number and type of PS in EU28 community pharmacies 17 -24 . This last fact is also related to the appearance of a new PS – the “new medicines service” – that was highlighted in some PGEU annual reports 18 ,25 . However, no accurate records of protocols or guidelines specifics for PS-T2DM’s implementation or provision were founded. This fact is an essential barrier to a complete understanding of the strategic planning of health systems in the EU28 for the eradication of T2DM supported by the collaboration of pharmaceutical care in primary care.

Analysis of PS-T2DM Provided in EU22 Countries: By Type, Subtype, and Category

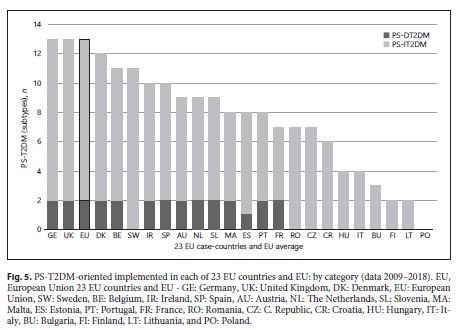

A set of detailed studies for all categories of PS-T2DM was found. They are related to a total of 22 EU countries – the “data set of case countries” (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, The Netherlands, and United Kingdom). Their correspondent studies were organized in table 2 and reorganized in a quantitative and qualitative approach in tables 3 and 4 , respectively. The remaining countries were excluded from this analysis due to the lack of data related to PS-T2DM implementation and/or provision between 2008 and 2018, and they are Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovakia, and Poland. The countries that presented the first concrete studies on the existence/implementation/provision of PS-T2DM were Malta, The Netherlands, and Denmark, in 2009. However, the United Kingdom was the country that published more studies about PS-T2DM (12 of 46).

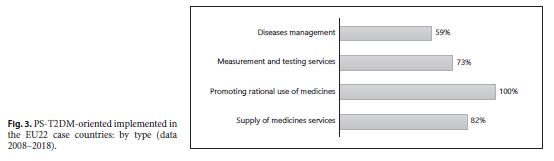

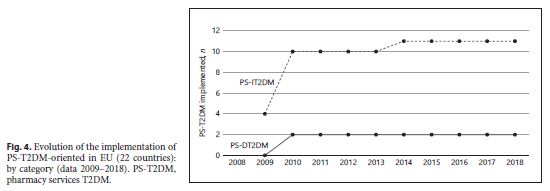

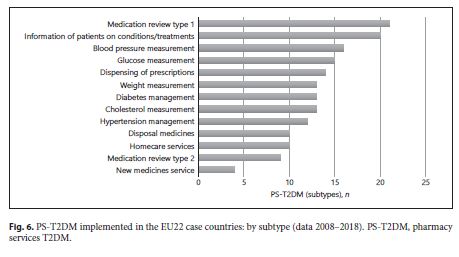

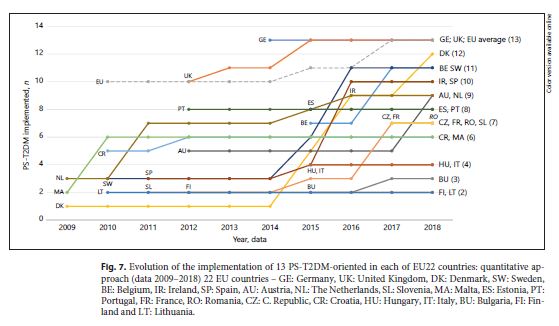

An increase of type and number of PD-T2DM, in general, was observed in all 28 case-countries, especially between 2009 and 2010. A strong influence of some countries in the results – Germany and the United Kingdom – was observed. They contribute to the T2DM implementation’s growth during the decade studied because they were the only 2 of 28 EU countries that implemented all 13 subtypes of PS-T2DM of the 2 categories (PS-DT2DM and PS-IT2DM). The type of PS-T2DM implemented in all EU22 case-countries was the “promoting rational use of medicines” service, and the least frequent was the “diseases management” service (59%) (Fig. 3 ).Regarding the implementation of 13 PS-T2DM subtypes, it was observed that: 21 countries implemented the “medication review type 1” service, 20 countries implemented the “information on patients on conditions/treatments” service, 16 countries implemented the “blood pressure measurement” service, 15 countries implemented the “glucose measurement” service, 14 countries implemented the “dispensing of prescriptions” service, 13 countries implemented the “weight measurement” and “diabetes management” services, 12 countries implemented the “cholesterol measurement” service and the “hypertension management” service, 11 countries implemented the “disposal medicines” service, 10 countries implemented the “homecare services” service, 9 countries implemented the “medication review type 2” service, and 4 countries implemented the “new medicines service” service (Fig. 4 - 6 ). Thus, between 2009 and 2018, there was an increase in the number of PS-T2DM implemented in the 22 countries, namely the PS-IT2DM (Fig. 6 , 7 ).

Evolution of the implementation of 13 PS-T2DM-oriented in each of EU22 countries: quantitative approach (data 2009–2018) 22 EU countries – GE: Germany, UK: United Kingdom, DK: Denmark, SW: Sweden, BE: Belgium, IR: Ireland, SP: Spain, AU: Austria, NL: The Netherlands, SL: Slovenia, MA: Malta, ES: Estonia, PT: Portugal, FR: France, RO: Romania, CZ: C. Republic, CR: Croatia, HU: Hungary, IT: Italy, BU: Bulgaria, FI: Finland and LT: Lithuania.

Analysis of the Existence of Regulation and Clinical Guidelines for DM or T2DM in EU28

In table 5 , it could be observed that the extent to which the different governments have embraced pharmaceutical care varies between EU countries. In some of them (e.g., Portugal and Spain), pharmaceutical care is officially recognized in the legislation, but it does not mean that pharmaceutical care is understood as an advanced service exclusively provided by CPH. Most of the countries have been involved in the fight against NCDs in the last decade and developed health policies and guidelines for DM and/or T2DM. However, only 3 countries reported regulation for T2DM (Austria, Latvia and Romania). Also, most of the countries (21 out of 28) have an entity attached to the Ministry of Health or equivalent, that was responsible for NCDs. In Belgium, for example, there are specific guidelines for T2DM, adopted from international and relative guidelines for prevention and treatment, applicable at local, regional, and national levels.

On the other hand, only 8 out of 28 countries have a multisectoral national operational, strategic, or action plan that integrates several NCDs and its associated risk factors. However, in 19 of the 28 countries, it was observed a multisectoral national policy cluster, as well as strategies or action plans, to discourage unhealthy diets and/or promote physical activity. Belgium is again relevant. Latvia as well due to its records of the existence of guidelines for T2DM, and its regulation. In addition, in most countries (23 of 28), there were evidence-based national guidelines/protocols/standards for the management of NCDs through a primary care approach. In this case, Latvia and Romania, which have records of the existence of guidelines for T2DM, and their regulation, are relevant. Regarding vigilance and monitoring programs for NCDs that allow the communication of information on the overall NCDs’ goals, it is recorded in 7 of the 28 countries, and Latvia is distinguished for the same reasons as mentioned above.

Discussion

Few studies address a concrete interaction between community pharmaceutical services and people with T2DM’s health outcome sets monitoring during the study period (2008–2018). The found evidence demonstrated both the benefit of DM management by CPH through these pharmacy services and the success of their implementation in terms of adherence to treatment and correct use of medicines 3 ,26 - 28 . Thus, the application of this close and permanent set of T2DM care services has become an essential model of qualified pharmacy practice for policy considerations 1 ,4 ,5 ,28 . The lack of evidence about the EU as a whole implies the detailed study of each country. Therefore, the European Union’s average was not a comparative factor, but only one of the observational units recorded the results in tables and figures.

Community Pharmaceutical Care Services for DM: Operational and Human ResourcesThe emergence of a new set of pharmacy services has emerged over the last decade to harmonize the different interpretations of its definition – the disease-oriented pharmaceutical care services (e.g., DM treatment, hypertension treatment, and treatment of asthma). Nevertheless, it has raised some questions within European health systems as to whether or not it is ethically permissible to limit pharmaceutical care only to groups of people with specific diseases, as DM 2 ,13 . However, studies report that, in the case of DM/T2DM, this care is undisputed and fundamental because it is a disease/set of diseases that needs a specific, close, and permanent assistance to provide: the diagnosis, even early (e.g., undiagnosed cases detection); the optimization of therapy; and monitoring/measurement of biochemical parameters. Moreover, EU community pharmacies have shown that they have invested in implementing these care services to assist health needs like DM 23 ,29 -31 . Also, CPH is responsible for providing this care. PGEU recognized CHP as the responsible person to prevent the reduction of the high risk of nonadherence, especially before and during the start of a new pharmacological treatment. Also, the WHO recognizes his role in pharmacotherapeutic’s patient follow-up in cooperation with GP and nurse 17 ,25 , 32 - 47 .

Community Pharmaceutical Care Services for DM: Legal Resources (Guidelines)In order to support human and operational resources, the implementation of pharmaceutical care for DM/T2DM depends on legal resources. Some studies and table 5 show not only the lack of evidence about the existence of guidelines, goals, and strategies for the practice of this care in community pharmacy but also in the primary care field, in general. Moreover, this is important for this discussion, because an effective response by a health system to health needs, considering the predictions of an increased disease burden, requires 2 essential tools: health planning and a robust multifactorial resource structure. In other words, these results led us to conclude that the failure of health systems to solve public severe health problems like DM is not only due to erroneous strategies for the development and implementation of primary health care services but also to planning failures. We found that health goals and strategies varied from country to country, meaning that some countries choose to develop independent policies or strategic plans, others include DM in an integrated NCDs’ policy, and other regions choose both.

Community Pharmaceutical Care Services for DM: Implementation in Each EU CountryOnly 16 of the EU28 countries implemented the 2 categories of PS-T2DM (PS-DT2DM and PS-IT2DM), and 22 of the EU28 countries implemented 1 subtype of PS-T2DM, at least. That is, all countries have implemented pharmaceutical care for DM in their community pharmacies, although in a service (e.g., medication review type 1) that can be used for other diseases (chronic or acute). Also, it is essential to note that the PS-DT2DM services are implemented in more than half of the countries, and the number of acceding countries has increased over time in the period of study (2008–2018) (tables 2 - 4 ). Furthermore, it could be a future trend of pharmaceutical patient care upgrading in terms of number and quality of the services provided in community pharmacies. It occurs because these services are included in the set of services classified in PGEU as “advanced services” 17. It signifies an extension and enhancement of primary health care provided for T2DM in community settings. We also observed an increase in the number of countries that implemented PS-T2DM over time, mainly between 2009 and 2010. Germany and the United Kingdom were the only countries that match the EU average, with the implementation of the total of selected PS-T2DM (13 in total) for the study. However, no evidence was found for PS-T2DM guidelines in these countries. In its turn, Lithuania had the lowest number of PS-T2DM implemented. However, it was the only country whose participation of pharmacists is mentioned in the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of T2DM besides Poland and Spain, both for DM.

There is a collective political and legal will on some EU countries to develop and implement adequate resources (human, operational, financial, and legal) for the provision of pharmaceutical services in community pharmacies to reduce the disease burden at local, regional, and global level. The contribution for the improvement of the accessibility, proximity, and equity of primary care provided in community pharmacies throughout the EU28 comes up with a new generation of T2DM primary care in community pharmacies – the professional PS-T2DM-oriented. This promising strategy for improvement of health outcome sets showed that they could have a consistent impact with some objectives of universal health coverage for DM/T2DM eradication. This fact was shown through the increase in specificity and number of PS-T2DM that were implemented, developed, and provided in community pharmacies since 2010. Nevertheless, T2DM has prevailed in the last decade at the regional level (EU28), so it is still insufficient to cover health needs related to this disease. So, it is necessary to develop new health policies that contribute to: expand the operational and legal structures of pharmacy services; to include community pharmacy as a mandatory element in primary care; to create an effective connection between the GP/nurse and the patient to perform the primary diagnosis with or without subsequent screening and pharmacotherapeutic follow-up over time; and to promote self-management of health as a way to involve the patient, making him responsible for the evolution of disease. Also, we need further studies to assess the impact of this new generation of pharmacy services on the global burden of this disease and to analyze the feasibility of developing uniformed PS-T2DM protocols/guidelines in harmony with the health care structure of each EU country. In Sweden, for example, health policies are highly focused on health determinants such as social and physical environment of the individual; whereas in The Netherlands and Denmark, priority is given to risk factors such as tobacco and alcohol and serious diseases such as DM and cardiovascular disease 5 ,10 ,11 ,48 ,49 . These two countries did not show evidence on the existence of official pharmaceutical care guidelines for T2DM and PS-T2DM, but almost all PS-DT2DM were implemented. Furthermore, here emerges the question, “How is pharmaceutical care implemented without legal support?” 23 ,48 ,50 . This fact should be part of the future evidence and put in practice by health systems.

Limitations of the StudyThe selected studies on the supply of pharmacy services for DM in the EU28 countries between 2008 and 2018 were heterogeneous in several aspects, such as target groups/age groups, health care providers (pharmacists, nurses, and other healthcare providers), disease or target disorder considered in the study, as well as means/strategies to evaluate outcomes and their approach. Also, the studies have shown to be unclear in terms of the organizational and operational strategy of implementing PS (of methodology/protocol/practitioners) and their adaptation to individuals or populations. Besides, the study found that the structure of these PS varies according to the legislation of each health system with regard to community pharmacy, pharmacist, and pharmaceutical care provision. Also, the type of DM of the most of studies explicitly referred to a type of DM, but somewhat generalized to the designation of “diabetes mellitus” or “diabetes.” This is one of the main limitations in the selection of study materials, and it implied that the analysis had to be reorganized, in studies with information on the new categories PS-DT2DM and PS-IT2DM.

Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes mellitus implies multimorbidity and polypharmacy, so people with this disease or at risk to develop it (prediabetes) should have a close, frequent, and rigorous monitoring of their health outcomes sets (e.g., parameter values and treatment adherence). EU28 community pharmacy services for T2DM have assumed this role in primary care networks over the last decade. This pharmaceutical patient care has been provided by the CPH. He manages the disease at a core, basic and advanced level. That is, CHP performs the diagnosis, the patient referral to the GP, and the pharmacotherapeutic follow-up at the community pharmacy. This is realized in the form of 13 subtypes of T2DM-oriented pharmacy services: 2 of them specific for T2DM and 11 for T2DM’s risk factors. The present study concluded that the implementation of this pharmaceutical care upgrading was increasing over the period of the study (2008–2018) in 22EU countries, at least. In addition, more evidence was found about these 13 subtypes in the United Kingdom, besides it being the country which gave more recognition to the CPH and pharmacy for the provision of advanced care services (“diabetes management”). However, most EU 28 countries do not have legal support (guidelines, targets, and strategies), and this can condition effective pharmaceutical assistance collaboration in the primary care network.

References

1 International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Brussels: IDF Publishing; 2016. [ Links ]

2 International Diabetes Federation. IDF Atlas. 9th ed. Brussels: IDF Publishing; 2019. [ Links ]

3 International Diabetes Federation. About diabetes 2017. Brussels: IDF Publishing; 2017. [ Links ]

4 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance: Europe 2018: state of health in the EU cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2018. [ Links ]

5 Mackenbach J, McKee M, editors. Successes and failures of health policy in Europe: four decades of divergent trends and converging challenges. Maidenhead (Berkshire): Mc- Graw Hill Education. Open University Press; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt125.002. [ Links ]

6 American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40(Suppl 1):S64-74. [ Links ]

7 Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013 Jan; 93(1): 137-88. [ Links ]

8 Marks L, Hunter D, Alderslade R. Strengthening public health capacity and services in Europe: a concept paper. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2011. [ Links ]

9 Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, et al.; Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 2009 Jun; 373(9679): 1993-5. [ Links ]

10 World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes. Geneva: WHO Publications; 2016. [ Links ]

11 Richardson E, Zaletel J, Nolte E; Joint Action CHRODIS. National diabetes plans in Europe: what lessons are there for the prevention and control of chronic diseases in Europe? Ljubljana: National Institute of Public Health; 2016. [ Links ]

12 McDaid D, Sassi F, Merkur S, editors. Promoting health, preventing disease: the economic case. Maidenhead (Berkshire): Mc- Graw Hill Education. Open University Press; 2015. [ Links ]

13 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2009. [ Links ]

14 Hughes JD, Wibowo Y, Sunderland B, Hoti K. The role of the pharmacist in the management of type 2 diabetes: current insights and future directions. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2017 Jan; 6: 15-27. [ Links ]

15 Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [ Links ]

16 Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Oct; 62(10):e1-34. [ Links ]

17 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. PGEU Annual Report 2010: Providing quality pharmacy services to communities in times of change. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2010. [ Links ]

18 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. PGEU Annual Report 2017: Measuring health outcomes in community pharmacy. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2017. [ Links ]

19 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. PGEU Annual Report 2013: Community pharmacy: the accessible local healthcare resource. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2013. [ Links ]

20 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. PGEU Annual Report 2014: Promoting efficiency: improving lives. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2014. [ Links ]

21 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union GEU. PGEU Annual Report 2015: Pharmacy with you through life. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2015. [ Links ]

22 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union PGEU. PGEU Annual Report 2016: Community pharmacy: a public health hub. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2016. [ Links ]

23 Mil J, Schulz M. Review of pharmaceutical care in community pharmacy in Europe. Harvard Health Policy Rev. 2006; 7(1): 155-68. [ Links ]

24 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. PGEU Annual Report 2017: providing quality pharmacy services to communities in times of change. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2017. [ Links ]

25 Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union. The community pharmacy contribution to sustainable health systems: opinion paper. Brussels: PGEU Publishing; 2018. State of Pharmaceutical Patient Care for Diabetes in EU28 Port J Public Health 2019;37:100-118 117 DOI: 10.1159/000506261 [ Links ]

26 Miksa MJ, Kalo I, Soares MA. PharmaDia?: improved quality in diabetes care: the pharmacist in the St. Vincent team: protocol and guidelines. In: 10th Annual Meeting of Euro- Pharm Forum: report on a WHO meeting, Dubrovnik, Croatia 12-14 October 2001. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2002. EUR/01/5036342.

27 Clement M, Bhattacharyya O, Conway JR. Is tight glycemic control in type 2 diabetes really worthwhile? Yes. Can Fam Physician. 2009 Jun; 55(6): 580-2. [ Links ]

28 Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990 Mar; 47(3): 533-43. [ Links ]

29 World Health Organization. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system: Part I and Part II. Copenhagen: WHO; 1994. WHO/ PHARM/94.569. [ Links ]

30 Funnell MM, Anderson RM. MSJAMA: the problem with compliance in diabetes. JAMA. 2000 Oct; 284(13): 1709. [ Links ]

31 Gallant MP. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Educ Behav. 2003 Apr; 30(2): 170-95. [ Links ]

32 Eades CE, Ferguson JS, O'Carroll RE. Public health in community pharmacy: a systematic review of pharmacist and consumer views. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jul; 11(1): 582. [ Links ]

33 McCann L, Hughes CM, Adair CG. A self-reported work-sampling study in community pharmacy practice: a 2009 update. Pharm World Sci. 2010 Aug; 32(4): 536-43. [ Links ]

34 Willis A, Rivers P, Gray LJ, Davies M, Khunti K. The effectiveness of screening for diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk factors in a community pharmacy setting. PLoS One. 2014 Apr; 9(4):e91157. [ Links ]

35 Nazar H, Nazar Z, Portlock J, Todd A, Slight SP. A systematic review of the role of community pharmacies in improving the transition from secondary to primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015 Nov; 80(5): 936-48. [ Links ]

36 Atkinson J, Pozo A, Rekkas D, Volmer D, Hirvonen J, Bozic B, et al. Hospital and Community Pharmacists' perceptions of which competences are important for their practice. Pharmacy (Basel). 2016; 4(2):e21. [ Links ]

37 Atkinson J, Paepe K, Pozo A, Rekkas D, Hirvonen J, Bozic B, et al. Does the subject content of the pharmacy degree course influence the Community Pharmacist's views on competencies for practice? Pharmacy (Basel). 2015; 3(3): 137-53. [ Links ]

38 Omboni S, Caserini M. Effectiveness of pharmacist's intervention in the management of cardiovascular diseases. Open Heart. 2018 Jan; 5(1):e000687. [ Links ]

39 Atkinson J, De Paepe K, Sánchez Pozo A, Rekkas D, Volmer D, Hirvonen J, et al. How do European pharmacy students rank competences for practice? Pharmacy (Basel). 2016 Jan; 4(1):e8. [ Links ]

40 Kwint H, Faber A, Gussekloot J, Bouvy L. Completeness of medication reviews provided by community pharmacists. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014; 39: 248-52. [ Links ]

41 Hogg G, Ker J, Stewart F. Over the counter clinical skills for pharmacists. Clin Teach. 2011 Jun; 8(2): 109-13. [ Links ]

42 International Diabetes Federation. Integrating diabetes evidence into practice: challenges and opportunities to bridge the gaps. Brussels: IDF Europe Publications; 2017. [ Links ]

43 George PP, Molina JA, Cheah J, Chan SC, Lim BP. The evolving role of the community pharmacist in chronic disease management: a literature review. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010 Nov; 39(11): 861-7. [ Links ]

44 World Health Organization on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Facets of public health in Europe. Organization 2014. Maidenhead (Berkshire): Open University Press; 2014. [ Links ]

45 Campos A, Simões J. O percurso da saúde: Portugal na Europa. Coimbra: Almedina; 2011. [ Links ]

46 Johnson JM, Carragher R. Interprofessional collaboration and the care and management of type 2 diabetic patients in the Middle East: A systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2018 Sep; 32(5): 621-8. [ Links ]

47 Rutter P, Brown D, Howard J, Randall C. Pharmacists in pharmacovigilance: can increased diagnostic opportunity in community settings translate to better vigilance? Drug Saf. 2014 Jul; 37(7): 465-9. [ Links ]

48 Allin S, Mossialos E, McKee M, Holland W. Making decisions on public health: a review of eight countries. Brussels: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2004. [ Links ]

49 Tamayo T, Rosenbauer J, Wild SH, Spijkerman AM, Baan C, Forouhi NG, et al. Diabetes in Europe: an update. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014 Feb; 103(2): 206-17. [ Links ]

50 World Health Organization. Joint FIP/WHO guidelines on good pharmacy practice: standards for quality of pharmacy services. Geneva: WHO; 2011. (WHO Technical Report Series; 961). [ Links ]

51 European Association of Employed Community Pharmacists in Europe. EPhEU: employed community pharmacists in Europe. [Internet]. Vienna: EPhEU Publishing; 2019. Cited 2019-02-12. Available from: https://epheu.eu/about-us/. [ Links ]

52 Langer T, Spreitzer H, Ditfurth T, Stemer G, Atkinson J. Pharmacy practice and education in Austria. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018 Jun; 6(3): 55. [ Links ]

53 Lemmens-Gruber R, Hahnenkamp C, Gössmann U, Harreiter J, Kamyar MR, Johnson BJ, et al. Evaluation of educational needs in patients with diabetes mellitus in respect of medication use in Austria. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012 Jun; 34(3): 490-500. [ Links ]

54 Martins SF, van Mil JW, da Costa FA. The organizational framework of community pharmacies in Europe. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015 Oct; 37(5): 896-905. [ Links ]

55 L'Office des Pharmacies coopératives de Belgique. "Pharmacien de reference": un nouveau service pour un meilleur suivi des patients chroniques. Bruxelles: OPHACO; 2017. [ Links ]

56 Petkova V, Atkinson J. Pharmacy practice and education in Bulgaria. Pharmacy (Basel). 2017 Jun; 5(3):e35. [ Links ]

57 Jonjic D, Grdinic V. Pharmacy in Croatia. Zagreb: Croatian Chamber of Pharmacists; 2010. [ Links ]

58 Mestrovic A, Stanicic Z, Hadziabdic MO, Mucalo I, Bates I, Duggan C, et al. Individualized education and competency development of Croatian community pharmacists using the general level framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012 Mar; 76(2): 23.

59 European Association of Employed Community Pharmacists in Europe. EPhEU: employed community pharmacists in Europe: more about pharmacy in Croatia. [Internet]. Vienna: EPhEU Publishing; 2019. Cited 2019- 02-12. Available from: https://epheu.eu/croatia-more-about-pharmacy/. [ Links ]

60 Deloitte Access Economics. Department of Health. Remuneration and regulation community pharmacy: literature review. Canberra: Deloitte Publishing; 2016. [ Links ]

61 Haugbølle LS, Herborg H. Adherence to treatment: practice, education and research in Danish community pharmacy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2009 Oct; 7(4): 185-94. [ Links ]

62 Søndergaard B. Implementation of pharmacy services in Denmark. Copenhagen: Association of Danish Pharmacies (Apotek); 2018. [ Links ]

63 Horvat N, Kos M. Contribution of Slovenian community pharmacist counseling to patients' knowledge about their prescription medicines: a cross-sectional study. Croat Med J. 2015 Feb; 56(1): 41-9. [ Links ]

64 Horvat N, Kos M. Slovenian pharmacy performance: a patient-centred approach to patient satisfaction survey content development. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011 Dec; 33(6): 985- 96. [ Links ]

65 Gmeiner T, Horvat N, Kos M, Obreza A, Vovk T, Grabnar I, et al. Curriculum Mapping of the Master's Program in Pharmacy in Slovenia with the PHAR-QA Competency Framework. Pharmacy (Basel). 2017 May; 5(2):E24. [ Links ]

66 Olave Quispe SY, Traverso ML, Palchik V, García Bermúdez E, La Casa García C, Pérez Guerrero MC, et al. Validation of a patient satisfaction questionnaire for services provided in Spanish community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011 Dec; 33(6): 949-57. [ Links ]

67 Sepp K. Critical pathways: the role of pharmacies in Estonia today and tomorrow. Tallinn: The National Institute for Health Development (Eestiapteek); 2015. [ Links ]

68 Leikola S, Tuomainen L, Peura S, Laurikainen A, Lyles A, Savela E, et al. Comprehensive medication review: development of a collaborative procedure. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012 Aug; 34(4): 510-4. 118 Port J Public Health 2019;37:100-118 Pizarro/Martins/Simões DOI: 10.1159/000506261

69 Svensberg K, Sporrong SK, Björnsdottir I. A review of countries' pharmacist-patient communication legal requirements on prescription medications and alignment with practice: comparison of Nordic countries. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015 Nov-Dec; 11(6): 784-802. [ Links ]

70 Supper I, Bourgueil Y, Ecochard R, Letrilliart L. Impact of multimorbidity on healthcare professional task shifting potential in patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care: a French cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov; 7(11):e016545. [ Links ]

71 Urbonas G, Jakusovaite I, Savickas A. Pharmacy specialists' attitudes toward pharmaceutical service quality at community pharmacies. Medicina (Kaunas). 2010; 46(10): 686-92.

72 Vella E, Azzopardi LM, Zarb-Adami M, Serracino- Inglott A. Development of protocols for the provision of headache and back-pain treatments in Maltese community pharmacies. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009 Oct; 17(5): 269- 74. [ Links ]

73 Wirth F, Tabone F, Azzopardi L, Gauci M, Adami M, Serracino-Inglott A. Consumer perception of the community pharmacist and community pharmacy services in Malta. JPHSR. 2010; 1(4): 189-94. [ Links ]

74 van Geffen EC, Philbert D, van Boheemen C, van Dijk L, Bos MB, Bouvy ML. Patients' satisfaction with information and experiences with counseling on cardiovascular medication received at the pharmacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2011 Jun; 83(3): 303-9. [ Links ]

75 Hugtenburg J, Borgsteede S, Beckeringh J. Medication review and patient counselling at discharge from the hospital by community pharmacists. Pharm World Sci. 2009; 31: 630-7. [ Links ]

76 Martins S, Costa F, Caramona M. Implementação de cuidados farmacêuticos em Portugal, seis anos depois. Rev Port Farmacoter. 2013; 5: 255-63. [ Links ]

77 Nachtigal P, Simunek T, Atkinson J. Pharmacy practice and education in the Czech Republic. Pharmacy (Basel). 2017 Oct; 5(4):e54.

78 Taylor J, Krska J, Mackridge A. A community pharmacy-based cardiovascular screening service: views of service users and the public. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012 Oct; 20(5): 277-84. [ Links ]

79 Twigg MJ, Poland F, Bhattacharya D, Desborough JA, Wright DJ. The current and future roles of community pharmacists: views and experiences of patients with type 2 diabetes. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013 Nov-Dec; 9(6): 777-89. [ Links ]

80 Twigg MJ, Desborough JA, Bhattacharya D, Wright DJ. An audit of prescribing for type 2 diabetes in primary care: optimising the role of the community pharmacist in the primary healthcare team. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2013 Jul; 14(3): 315-9. [ Links ]

81 Morton K, Pattison H, Langley C, Powell R. A qualitative study of English community pharmacists' experiences of providing lifestyle advice to patients with cardiovascular disease. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2015 Jan-Feb; 11(1):e17-29. [ Links ]

82 Longley M, Riley N, Davies P, Hernández- Quevedo C. United Kingdom (Wales): Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2012; 14(11): 1-84. [ Links ]

83 Twigg MJ, Wright DJ, Thornley T, Haynes L. Community pharmacy type 2 diabetes risk assessment: demographics and risk results. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015 Feb; 23(1): 80-2. [ Links ]

84 Andreassen LM, Kjome RL, Sølvik UØ, Houghton J, Desborough JA. The potential for deprescribing in care home residents with Type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016 Aug; 38(4): 977-84. [ Links ]

85 Lowrie R, Mair FS, Greenlaw N, Forsyth P, Jhund PS, McConnachie A, et al.; Heart Failure Optimal Outcomes from Pharmacy Study (HOOPS) Investigators. Pharmacist intervention in primary care to improve outcomes in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Eur Heart J. 2012 Feb; 33(3): 314-24. [ Links ]

86 Ridge K. The review of specialist pharmacy services in England. London: NHS England; 2014. [ Links ]

87 Ayorinde AA, Porteous T, Sharma P. Screening for major diseases in community pharmacies: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013 Dec; 21(6): 349-61. [ Links ]

88 Sandulovici R, Mircioiu C, Rais C, Atkinson J. Pharmacy practice and education in Romania. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018; 6(1): 5. [ Links ]

89 Montgomery AT, Kettis Lindblad A, Eddby P, Söderlund E, Tully MP, Kälvemark Sporrong S. Counselling behaviour and content in a pharmaceutical care service in Swedish community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci. 2010 Aug; 32(4): 455-63. [ Links ]

90 International Pharmaceutical Federation. Pharmacy at a glance 2015-2017. The Hague: FIP Publishing; 2017. [ Links ]

91 World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases: country profiles 2014. Geneva: WHO Publishing; 2014. [ Links ]

92 Sterne J, Hernan M, Reeves B, Savovic J, Berkman N, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMC. 2016;355:i4919. [ Links ]

93 World Health Organization. Clinical Guidelines for Chronic Conditions. Geneva: WHO Publishing; 2013. [ Links ]