Introduction

On December 8, 2019, a pneumonia outbreak of unknown etiology was first identified in Hubei City, Wuhan province, China. Chinese CDC reports the occurrence to the World Health Organization (WHO) China Country Office on December 31, 2019 (1, 2).

WHO names the disease COVID-19, an acronym for coronavirus disease 2019, on February 11, 2020 (3). The agent causing the infection was a novel coronavirus designated SARS-CoV-2 by the Coronavirus Study Group (4, 5).

The disease spreads fast across the country and, soon after, across the world leading the WHO to declare the COVID-19 outbreak as a global health emergency, on January 30, 2020 and as a global pandemic on March 11, 2020. The last time had been in 2009 for the H1N1 influenza pandemic (6, 7). Infections from SARS-CoV-2 are now widespread (8).

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans, the third that can cause severe disease, but the first and only human coronavirus with pandemic potential (9-11). There is an equal likelihood of contagion for any person or worker. When we consider healthcare workers, namely, the ones dedicated to the diagnosis, treatment and care of infected patients, or laboratory professionals that directly manipulate biological products containing the virus, one could say that they have a specific risk that bears a higher probability of infection, which necessarily determines the need for specialized protection measures (12). Similar to the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2003-2004 and the MERS outbreak in 2012, there were early reports of frequent transmission to healthcare workers (HCW), including several with fatal outcome (13). They are expected to be one of the groups most exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and surveillance of the proportion of seropositive HCW is an important indicator of the spread of the virus (14).

Our hospital center identified its first COVID-19 confirmed case on March 9, 2020, in a 6-day hospitalized patient. The first confirmed COVID-19 in a HCW happened 3 days later, in a nurse with a probable epidemiological link related to the first confirmed patient. The Occupational Health Department (OHD) started its follow-up program of risk contacts and suspected cases evaluation that ended up with the development of a new dashboard, which allows daily reports to each involved department or ward supervisor, hospital directors and Portuguese Health Authority.

The health information system includes the standardization of criteria and the dissemination of data processing methodologies in order to allow the comparison of health indicators that will provide information on best practices (15, 16).

Our goal is to ensure the transparency of the entire COVID-19 prevention process in the OHD, fundamental for HCW management decisions (17).

Objectives

Our study’s first goal is to describe and characterize the impact of the first 3 months of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte (CHULN) quantified in the total number of cases identified, number of suspected cases officially reported to the OHD and their clinical and epidemiological characteristics.

Our second objective is to report the performance of the CHULN OHD and the impact of the pandemic on the CHULN HCW and its adaptation across national, regional, and institutional epidemiological evolution.

Materials and methods

In order to answer our first objective, we developed a cross-sectional study, involving all 7,220 workers of the CHULN, between March 11 and June 12. Our inclusion criteria were: (1) being a CHULN HCW; (2) with symptomatology suspicion of CO VID-19; (3) having a high-risk or low-risk contact with a known COVID-19 patient or colleague. No exclusion criteria were listed. Participation was voluntary. To meet our second objective, we carried out a narrative analysis of the OHD performance, during the evolution of the pandemic, and its adaptation effort by developing a software application (dashboard) to help gather, process, study and provide all data to all relevant partners.

In accordance with the Portuguese Health Authority, ECDC and the WHO, we use the following definitions: (i) symptomatology suspicious of COVID-19, we (18) included any HCW with at least one of the following symptoms: cough, fever, shortness of breath, sudden onset of anosmia, ageusia or dysgeusia (additional less specific symptoms included headache, chills, muscle pain, fatigue, vomiting and/or diarrhea); (ii) high-risk exposure (close contact), we considered any HCW providing care to a COVID-19 confirmed case or handling specimens from a COVID-19 case, without recommended Personal Protective Equipment (or with a possible breach of PPE) or having had face-to-face contact with any COVID-19 case within 2 m for >15 min (18-20); (iii) low-risk exposure was defined as any healthcare worker providing care to a COVID-19 case, or laboratory workers handling specimens from a COVID-19 case, wearing the recommended PPE or having had face-to-face contact or been in a closed environment with any COVID-19 case within 2 m for <15 min (18-20).

All selected cases whether, self-reported or reported by the wards, underwent a detailed medical interview in order to discriminate any associated symptoms and to scrutinize the nature of the contact with the aim of classifying the associated infection risk. All symptomatic HCW underwent an immediate nasopharyngeal swab to determine the presence of SARS-CoV-2 through a Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test. All asymptomatic high-risk contacts performed a nasopharyngeal swab to determine the presence of SARS-CoV-2 through a RT-PCR 4-5 days after the suspicious contact. All laboratory-positive cases begun sick leave and were reported to the national CO VID-19 patient registry. All laboratory-negative persons as well as all asymptomatic low-risk contacts begun an active daily symptom surveillance until the 14th day after the suspected contact and were reported to the OHD in case of any symptomatology. Any set of HCW being surveyed from one common COVID-19 patient were grouped in a cluster. Data were gathered from the CHULN OHD digital archive.

Results

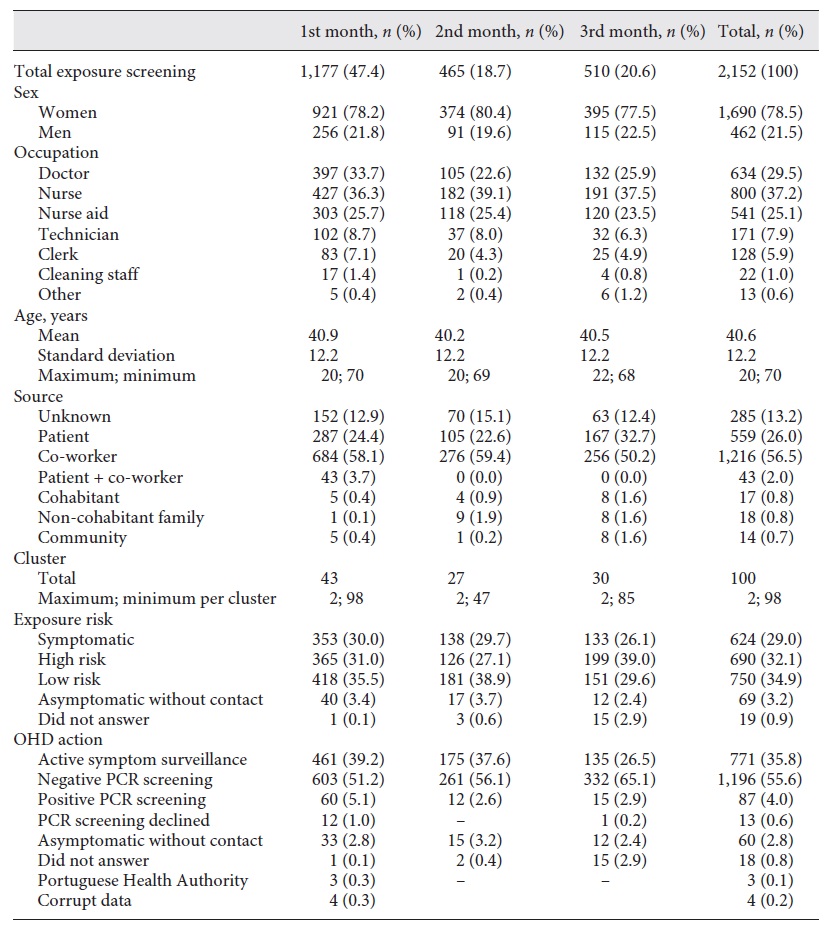

Over the first 3 months, 2,152 HCW were screened (which represent 29.8% of the total HCW population), grouped in 100 separate identifiable clusters, each one ranging from 2 to 98 HCW.

Our screened population (Table 1) had a mean age of 40.6 years and was composed mainly of females (n = 1,690; 78.5%). The most prevalent occupations screened were nurses (n = 800; 37.2%) followed by doctors (n = 634; 29.5%) and nurses aid (n = 541; 25.1%). Technicians and clerks had a minor impact (n = 171; 7.9% and n = 128; 5.9%, respectively).

One relevant fact uncovered was that the main source of potential infection and cluster generating screening procedures was co-worker related (n = 1,216; 56.5%). A patient source or a combined patient co-worker source was only accountable for 559 (26%) and 43 (2%) of cases, respectively. In 285 of the situations screened (13.2%), no source was identified. Familial and community sources had residual influence on the cases screened. The relative proportions of all variables identified remained constant throughout the 3 months of screening.

Risk classification was evenly distributed with an overall prevalence of 29.0, 32.1 and 34.9% for symptomatic HCW, high-risk and low-risk exposure, respectively.

During this first trimester, 1,283 RT-PCR were prescribed, which diagnosed 87 cases of COVID-19 among HCW (6.8%) which represent 4.0% of screened HCW and 1.2% of the total HCW. By the end of June, Portugal counted 42,171 confirmed cases (about 0.41% of the Portuguese population) (21, 22). During the course of our study, Portugal had a 14-day incidence rate average of 48.94 per 105 (reaching a 103.4 peek by week 15) (8).

Discussion

The 1.2% infection rate among HCW and the 6.8% of positive results obtained from all swabs prescribed in our study during the first 3 months of the pandemic were considerably lower than the ones found in the literature.

Wu and McGoogan (2) found an incidence of CO VID-19 among HCW of 3.8% (n = 1,716 HCW confirmed cases out of 44,672 total confirmed cases). Within the same time span, but in a Tertiary Hospital in Wuhan, China, Lai et al. (23) found an infection rate of 1.1% (110 of 9,684) among hospital HCW.

In Lombardy, Italy, one study found 8.8% (n = 139/1,573) of positive results (24). Although we could not find a concrete regional 14-day incidence rate per 105 data, by the time of the study, Lombardy was the most affected Italian region (25). In Verona, a total of 11,890 specimens collected in a combined mass screening and contact tracing strategy targeting close contacts, 238 positive swabs were obtained, yielding a cumulative incidence of 4.0% (25). The higher results could be explained because Italy reported a much higher incidence of disease in the community (128,948 confirmed cases which account for about 0.2% of the total population) (8).

In a Madrilene hospital 11.6% (n = 791) of all hospital HCW tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (38%) (26). This result is higher than ours because a high 14-day incidence rate was observed (8).

In Newcastle, researchers found 14% (n = 240) positive tests for HCW (27). At the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, 282 HCW were positive for SARS-CoV-2, which represents a 1.65% cumulative incidence out of the 17,000 employed staff (28).

In the Netherlands, a study involving 1,653 symptomatic HCW, 6% (n = 86) had a positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test (1%) (29).

In our OHD CHULN, we chose to classify and stratify the risk of exposure (18-20) and to identify the most probable source of infection rather than to infer the risk and source of infection by relying on the characteristics of specific HCW activities such as working in the first line versus non-first line of care, or working in a COVID versus non-COVID dedicated ward or ICU, or yet dealing directly or not with patients as some of the cite authors do (2, 23-29). By doing so, we found that 56.5% of potential HCW infection and cluster generating screening procedures were co-worker related. Regardless of the specific activity, a patient source or a combined patient/co-worker source was only accountable for 26 and 2% of cases, respectively and in 13.2% of the situations screened, no source was identified. As familial and community sources had residual influence on the cases screened, our data point to the fact that in the first 3 months of pandemic in our hospital centre, HCW mainly infecting each other during meals, break periods or in locker rooms.

Since early January, CHULN OHD became involved in the adaptation effort to the new reality through: (1) articulation with other hospital sectors in the design of a contingency plan; (2) development of training and information actions for HCW; (3) design and implementation of a surveillance plan of HCW with exposure to COVID-19 patients and early diagnosis of positive cases; (4) identification of HCW considered to have greater sensitivity to the development of disease with greater severity, that allow ending with a dashboard that help OHD managing HCW health and prevention strategies.

Conclusions

Our preliminary results demonstrate a lower infection rate among HCW than the ones commonly found in the literature. The main source of infection seemed to be co-worker related rather than patient related. New preventive strategies would have to be implemented in other to control SARS-CoV-2 spread.

The generalized use of the software application developed in our hospital would be beneficial not only to optimize human resources, but also to standardize data upload to regional and national authorities and to provide common ground to scientific pandemic impact comparison.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank nurses Ana Furtado, Isabel Pereira, Regina Rocha and Graça Temudo and our clerk Marina Xavier. The authors also would like to acknowledge the effort carried out by Dr. Francisco Caridade and all his H2ST crew that relentlessly worked in the development of our healthcare management software.

Statement of ethics

This research complies with the guidelines for human studies and was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki receiving the scientific ethical approval of the Lisbon’s Medical Academical Center and the Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte Ethics Committee. Gathered data were based on SCHULN OHD clinical records and were previously anonymized, thus informed consent was not required.

Author contributions

L.M.-G. is accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. L.M.-G. and E.S.-L. were responsible for data acquisition, design, analysis, and interpretation of data. J.R., D.F., A.C., R.L., J.S., C.A., and O.S. were responsible for data acquisition. E.S.-L., F.S., and A.S.-U. were re- sponsible for revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.