Introduction

The demand for a healthy condition depends largely on the individual’s ability to understand what is around us, which is a determinant for our global wellbeing 1. This capacity is entailed in the concept of health literacy that becomes known in the 1970s 2 and has been discussed until now 3 regarding its recognized complexity and multidimensionality. The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed one of the most cited definitions of health literacy, which states that “cognitive and social skills” are essential to determine the individuals’ “motivation and ability to gain access to understand and use the necessary information to promote and maintain good health” 4.

Health literacy is a dynamic concept, relying on a complex set of interactions regarding health and disease that result from people’s knowledge, perceptions, and behaviours, depending on socioeconomic and cultural conditions as well as embracing different skills (writing, reading, listening, speaking) 5. Three major dimensions are commonly referred to as functional (oral and writing comprehension and numeracy skills); interactive (seeking health information); and critical (the use of health information to promote health and wellbeing) 6,7.

Individuals with low literacy levels are expected “to have a poor health status, a lower quality of life, and a shorter life expectancy. Research indicates that low health literacy levels could increase poor health outcomes, higher risk of disease and disability, higher use of healthcare services (especially the emergency services), and a higher risk for hospitalization, which increases the costs for healthcare systems” 8.

The growing concern shown by the institutions and organizations related to health and healthcare around the world highlights the importance of evaluation and measurement of health literacy levels in populations as well as the promotion of health literacy programmes and initiatives in the communities reinforcing a public health-driven approach 9. The importance given to the assessment of health literacy represents a growing trend reinforcing the importance of a priority issue in the health literacy research field. The number of validated instruments has significantly increased in the last years, as referred by Nguyen et al. 10, with over 150 different measures. Despite this advance, there is not a consensual standard measure for health literacy. The complexity of this social construct and multidimensionality of the available definitions associated with the respective measures that ensure the assessment of health literacy has become a challenge that concerns the comparison of results across studies or populations 10,11.

Despite the convergence of the main results in revealing low health literacy levels, the diversity of instruments evidences the use of different approaches and operationalizations 12, including the focus on different dimensions such as functional, communicative, or critical 13, and aspects of measurement: individual or personal versus population; objective versus subjective; performance-based versus self-reported; general health literacy versus disease or condition-specific measures as indicated in several review studies 10,12,14-19 making it difficult to compare results obtained from different instruments. In sum, research suggests that health literacy measurement should be better aligned with health literacy definitions as well as the context where the measures are applied, thereby justifying the need to analyse the existing measures as intended in this study.

Bearing in mind the international efforts to prioritize health literacy and its measurement, Portugal is not an exception 20,21. Different studies using the Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU PT) to measure health literacy in the Portuguese population revealed an overall limited health literacy at the individual and the community levels: 79% of the population with “inadequate” and “problematic” levels in 2014 22; 61% of the population surveyed with “inadequate” or “ill-health” levels in 2016, contrasting with the average of other European countries surveyed (49%)1 23. These results are in line with a sociocultural enclosure anchored in high illiteracy levels of the Portuguese population for many decades 24,25.

The above-mentioned results highlight the importance of the implementation of national programmes to improve health literacy aiming for a significant reduction in the burden of diseases through adequate healthcare use, the implementation of prevention strategies, and health promotion. To date, the research in this field made in Portugal is still insufficient, and the same happens with initiatives and programmes that are available to raise awareness about the importance of health literacy as well as the measurement of health literacy levels in the Portuguese population. It passed 20 years, 1994-2014, between the first national study of literacy conducted in Portugal and the first studies on health literacy assessment in our population as already referred to 22.

Despite that, in the last decade, there has been a growing concern of the national health authorities to include health literacy in the picture through the launch of the National Health Literacy and Self-Care Program in 2016 26 and the National Health Literacy Action Plan for 2019-2021. In this sense, the primary goal of this research is to conduct a systematic literature review to identify the existing measurement instruments adapted or developed to evaluate health literacy in different groups of the Portuguese population as well as the studies that were involved in the adaptation or development of those instruments. Discussion on limitations and future directions and implications for health literacy research in Portugal will also be presented according to the results obtained in this research.

Methods

A comprehensive search that aims to systematize and understand the available knowledge about health literacy measurement in Portugal was conducted to identify assessment tools and studies developed for the different target groups. PRISMA guidelines were followed whenever applicable to conduct this study (online suppl. Material 1; see Https://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000525890 for all online suppl. material) 27.

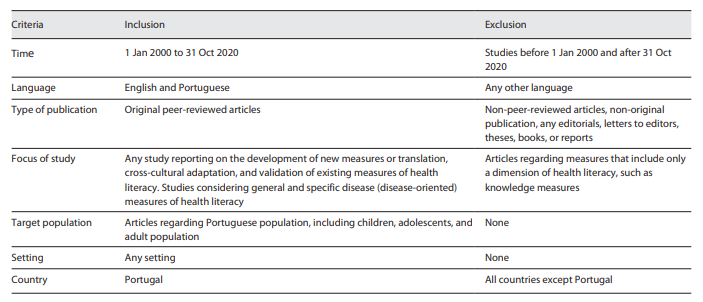

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined, as presented in Table 1, in English and Portuguese language original peer-review articles from 1 January 2000 to 31 October 2020. The time frame set for this search did not consider publications before 1 January 2000 once the concept of health literacy was not yet quite disseminated or identified as a priority in the national health promotion scenario. Articles including the development of new measures or translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of existing measures of health literacy were considered. Studies considering general and specific disease measures of health literacy were also included to broaden the insight of this field. Assessment tools that include only a dimension of health literacy, such as knowledge, were excluded from the scope of this work since we intend to study the evaluation instruments that embrace a comprehensive concept of health literacy dimensions.

Comprehensive Search

The search was carried out on digital databases through different platforms that are available in our host institution: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science (Medline; SciELO Citation Index), and EBSCOHost (Academic Search Ultimate; APA PsycArticles; APA PsycInfo; Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection; Education Source; ERIC; Fonte Acadêmica; Sociology Source Ultimate). The digital search was complemented with a review of the bibliographic references of the included studies.

Search and article selection were conducted between May and October of 2020. Keywords used in the search included health literacy; assessment or evaluation; and Portugal, in English and Portuguese language. Detailed information about the search strategy for each database can be found in online supplementary Material 2 27. The selection process includes the identification of the records, their screening, and at last the selection of studies to be included in the analysis.

The literature search and the selection of the studies to be included in the analysis were conducted by a team of three researchers with backgrounds in health and social sciences research. Differences and discrepancies that were found during the process were solved through discussion by the team involved in the process.

Analysis of the Selected Publications

The selected publications were analysed regarding different content aspects that provide an overview of the Portuguese context regarding health literacy measurement including the aim of the study to determine whether it is the development of a new measure or the translation and/or adaptation of an existing measure as well as the domains and dimensions of the instruments according to different health literacy definitions. The number of items for each instrument and scoring (minimum and maximum score) as well as cut-offs when they are available was also analysed. Information regarding high or low literacy scores was also included when available. The target population of the studies was assessed regarding age, geographic location of the study (Portugal (mainland and/or autonomous regions], one or several regions, counties, or cities), and if it is a general measure or if it is targeted to a specific group of the population. Information on sampling methods (probabilistic or non-probabilistic) and techniques used, when available, was also described, as well as the sample size of the validation study. Data collection time or period; mode and time of administration; target of the instrument to a specific disease or group of diseases; and the instrument availability in the publication were also included in the analysis of the publications. The information extracted from the publication concerning the different characteristics stated above will allow an overview of the existing measures as well as the establishment of possible comparisons for other studies that use the same instruments.

Reliability and validity were also described to analyse the quality of the publications that were included in the study. Regarding reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was described as a measure of internal consistency categorized from questionable to very good (Cronbach’s α: <0.7 = poor; 0.7-0.8 = acceptable; 0.8-0.9 = good; >0.9 = very good) 28. Test-retest (performed or not performed) was also used as a reliability measure. Other measures of reliability were described when performed in the studies that were analysed (e.g., intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]). Validity was analysed regarding the type of validity used in the study (content, construct, and criterion-related) 29.

Results

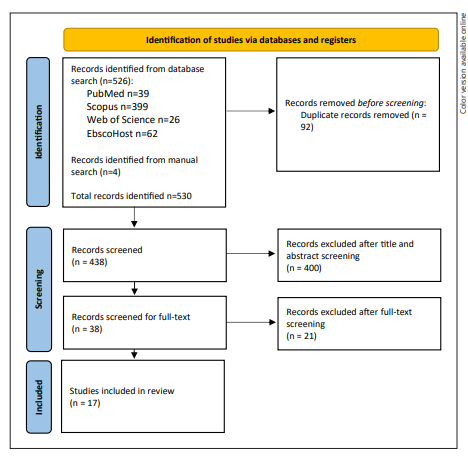

This comprehensive review is focused on the existing literature about health literacy measurement in Portugal, including generic and specific disease context health literacy measures. The search process identified a total of 526 publications matching the search criteria (PubMed n = 39, Scopus n = 399; Web of Science n = 26; EBSCOHost n = 62) and the manual search led to the identification of an additional n = 4 articles, so the total number of articles identified was 530 as described in the adapted PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1) 27. After the screening process described above and shown in Figure 1, 400 records were rejected, and 38 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. In the end, 17 studies were analysed 23,30-45.

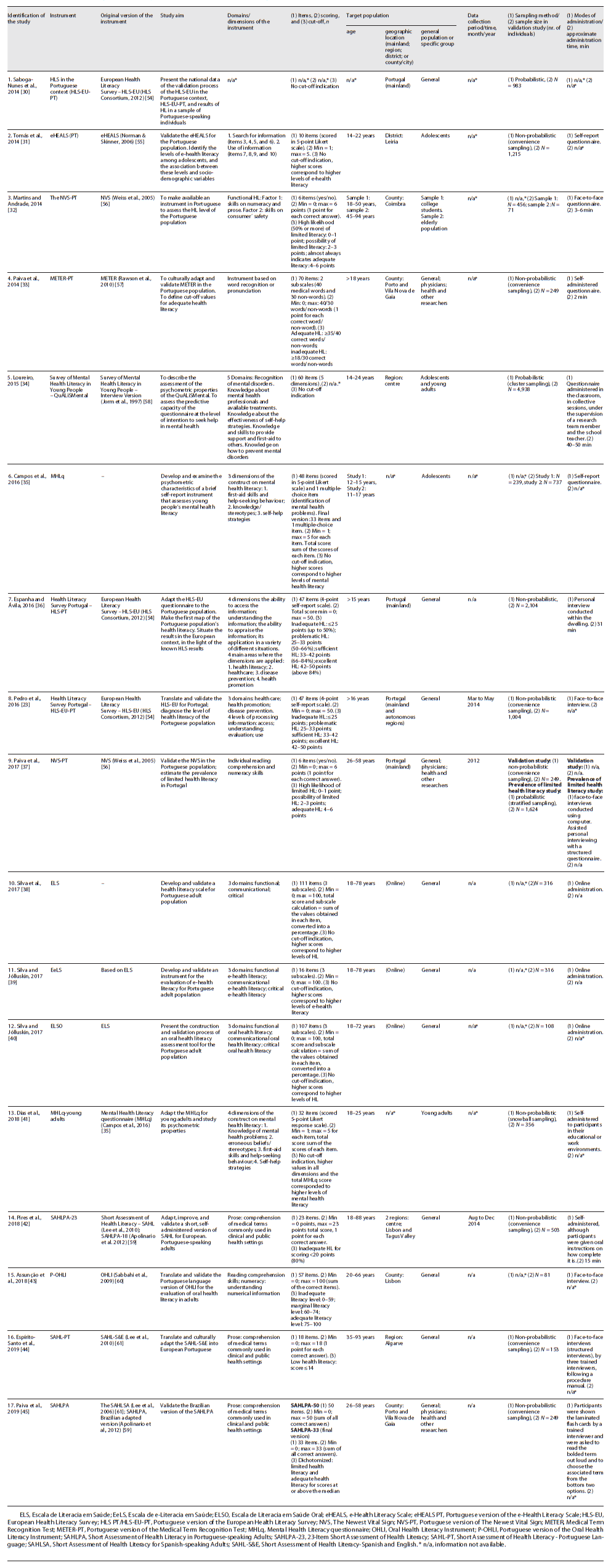

Table 2 presents the results of the analysis that integrated this review regarding a set of criteria that the authors considered relevant to the purpose of this study. A total of 17 publications were analysed, and 11 different instruments to measure health literacy in different groups of the Portuguese population were identified, comprising: 7 general measures of health literacy, including e-health literacy 23,30-33,36-39,42,44,45; 2 instruments focused on mental health 34,35,41; and 2 focused on oral health literacy 40,43. Four instruments are the object of study of more than one publication: 3 publications are related to the HLS 23,30,36 and the Short Assessment of Health Literacy (SAHL) instruments 42,44,45; 2 publications are related to the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) 32,37; and other 2 focused on the Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire (MHLq) 35,41.

The selected publications were further analysed regarding different content aspects, as detailed in Tables 2 and 3: the aim of the study; domains and dimensions of the instruments; the number of items, scoring, and cut-off; target population including age, geographic location, and general or specific group of the population; sampling and sample size; data collection; mode of administration; reliability and validity of the instrument; target to a specific disease or theme; and the instrument availability. All the publications analysed were published between 2014 and 2019. The majority of the publications (12 out of 17) were published in international journals and only 5 were in national publications. Also, 12 out of 17 publications analysed refer to instruments that have been previously developed to measure health literacy in other countries and populations, so they refer to the translation and/or cross-cultural adaption and validation of the instruments to measure health literacy in specific groups of the Portuguese population 23,30-34,36,37,42-45. Only 5 publications target instruments that were specifically developed for the Portuguese context 35,38-41. Furthermore, the analysis of the publications selected for the study revealed that 5 publications refer to the aims of the study, the assessment of health literacy levels, beyond the translation and adaptation of the instruments 23,30,31,36,37.

The domains and dimensions of health literacy of the different instruments were analysed regarding the different models and definitions that were adopted by the authors of the instruments to assess health literacy. Several studies are focused on basic skills such as reading, writing, pronunciation, comprehension, and numeracy. In this category, we included 7 publications concerning 4 instruments: NVS 32,37; the Medical Term Recognition Test (METER) 33; SAHL 42,44,45; and the Portuguese version of the Oral Health Literacy Instrument (P-OHLI) 43.

Other 3 publications 23,30,36 are grounded on the HLS and the conceptual model proposed by Sørensen et al. 3 that establishes an association between three domains ‒ healthcare; disease prevention; and health promotion ‒ and four dimensions regarding information relevant to health: access/obtain, understand, process/appraise, and apply/use. Three other publications, such as those using the Health Literacy Scale, e-Health Literacy Scale (EeLS), and the Oral Health Literacy Scale (ELSO), are focused on three domains: functional, communicational, and critical 38-40, following Nutbeam 4.

The 3 publications regarding instruments to assess mental health literacy 34,35,41 are focused on specific knowledge of the construct of mental health literacy that includes the ability to recognize mental disorders, seek help, prevent and provide first-aid as well as prevent mental illness. The publication of the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) (PT) 31 is focused on the search and use of information.

The analysis of the publications that integrate this study also shows diversity in terms of the number of items, scoring, and cut-off to classify and identify health literacy levels in individuals. The number of items of the instruments in the selected publications varies from 6 32,37 to 111 items 38.

The publications focused on the Portuguese version of the NVS (NVS-PT) 32,37 show that it is the shortest instrument, only with 6 items to assess health literacy. Two instruments, Health Literacy Scale 38 and the OHLS 40 have 111 and 107 items, respectively, and they are fully addressed in the studies. The 3 publications regarding the SAHL instrument 42,44,45 revealed different versions of the instrument which concern the number of items of the instrument, a version with 18 items 44, another with 23 items 42, and a long version with 33 items 45. Scoring and cut-off information were not available in 2 publications 30,34, the other publications reported minimum and maximum scores according to the characteristics of each instrument, cut-off information, and/or scoring and relation to high or low/limited health literacy.

The age of the target population of the selected studies can be categorized into three categories: adolescents (12-18 years); young adults (18-25 years), and adults (>25 years). However, the majority of the studies (13 in 17) were conducted on young adults and/or adults 23,32,33,36-45.

In which concerns to the geographic location where the studies were implemented, only 1 study covered the entire Portuguese territory (mainland and the autonomous regions) 23, 3 studies covered Portugal’s mainland 30,36,37, and the remaining studies were implemented in specific regions, districts, or cities of the mainland. It was also noted that 3 were implemented online 38-40.

In more than half of the studies, 9 targeted the general population 23,30,36,38-40,42-44, while others included specific groups of the population such as adolescents and young adults. Only 3 studies 23,37,42 reported data collection period/time, so differences in the time frame between data collection time and publication date were not analysed.

Regarding the sampling method, 2 studies 30), )34) used a probabilistic method, and 9 23,31,33,36,37,41,42,44,45 a non-probabilistic including convenience, or snowball sampling. Sample sizes are variable in the publications that were analysed, with a minimum of N = 81 43 and a maximum of N = 4,938 individuals 34 regarding the P-OHLI and the Questionnaire for Assessment of Mental Health Literacy (QuALiSMental), respectively.

Moreover, which concerns the mode of administration of the instruments, 5 publications refer that the instruments were self-administered or self-report 31,33,35,41,42 and 6 publications identify face-to-face interviews as the technique to collect the data 23,32,36,37,43-45. “Online administration” to perform data collection was mentioned in 3 publications 38-40.

Regarding the information available about the approximate time of administration of the different instruments, it varies between 2 and 50 min. The NVS-PT and METER-PT are quick to use 32,33,37. On the other hand, the HLS and the QuALiSMental need more time to be completed, between 30 and 50 min 34,36. At last, the time of administration of the SAHL stands within the time of the instruments referred above, and it takes 15 min to be completed 42.

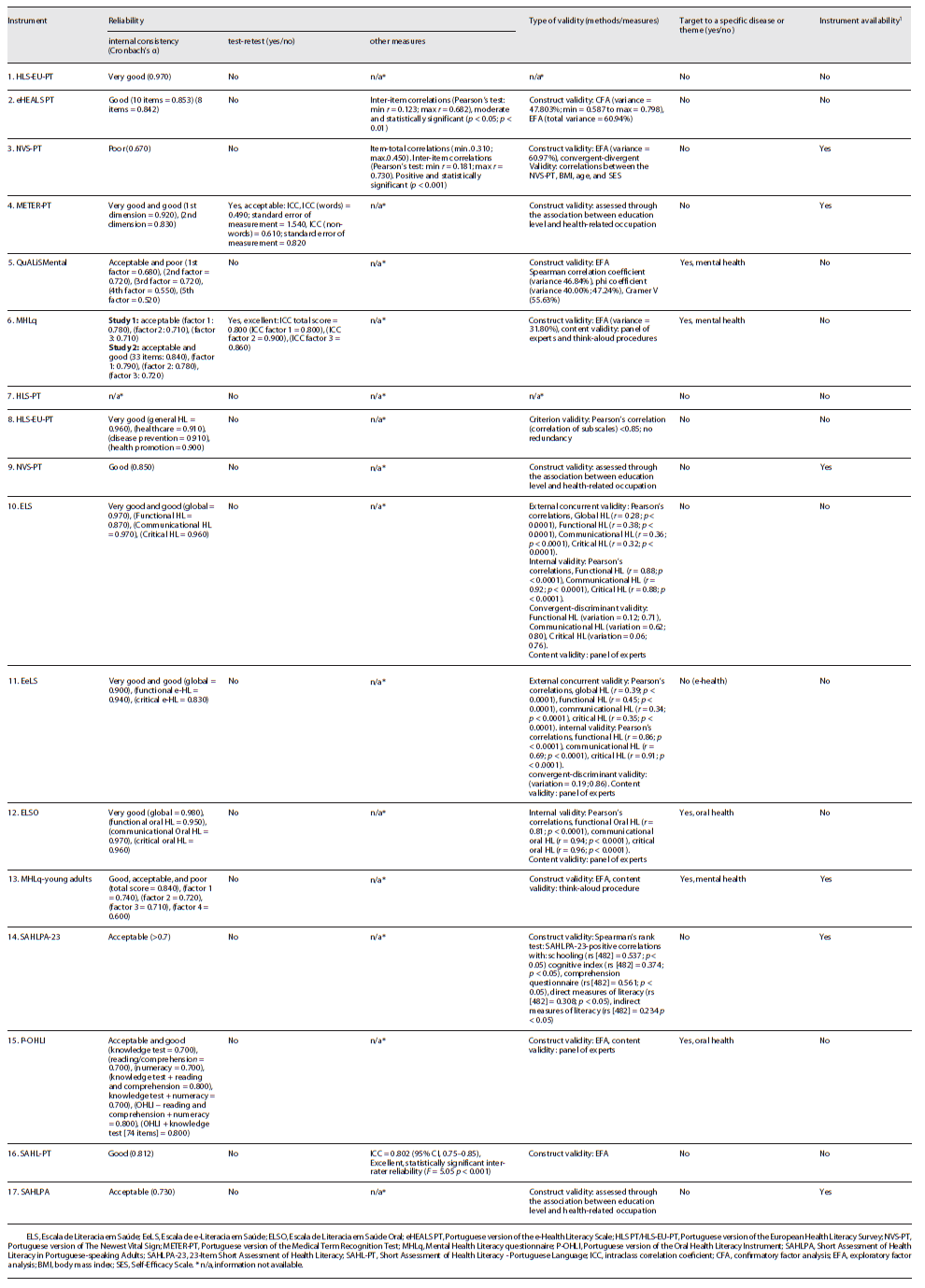

In which concerns to reliability, 16 out of 17 publications presented Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.520 34 and 0.980 40 to assess internal consistency. The results observed for Cronbach’s alpha including scale and subscale values vary from poor to very good. Poor internal consistency was just observed in 1 study and a particular subscale of that instrument 34 Indicating that almost all studies selected for this analysis are reliable.

Test-retest was also used to analyse reliability; however, test-retest was only reported in 2 publications 33,35. In these publications, test-retest was assessed using ICC, and the values presented vary from 0.490 to 0.900, indicating an acceptable to excellent reliability. In 3 publications 31,32,44, other measures were used to assess reliability including inter-item and item-total correlations (Pearson’s test) and ICC as detailed in Table 3.

The validity of the instruments was analysed regarding the type and measures/methods used to assess it. Results show that 14 publications report construct validity, and 7 of those publications 31,32,34,35,41,43,44 describe it through exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Other types of validity and measures or methods including content and criterion validity were also reported as detailed in Table 3. Publications regarding HLS 23,30,36 do not report construct validity. Only 6 out of 17 of the publications analysed have the instrument fully available 32,33,37,41,42,45.

Discussion

The analysis conducted in the 17 studies included in this review has found 11 different instruments that were adapted or developed to measure health literacy in different groups of the Portuguese population, mainly adults, adolescents, and young adults, focusing on general (including e-health) and specific (mental or oral) health literacy. The analysis performed shows that concerning the focus of health literacy measures described in the selected publications, the majority of the articles (N = 11 ‒ 23,30-33,36-39,42,44,45) revealed the instruments are general measures of health literacy, including the assessment of e-health literacy. Only 5 publications refer to instruments that intend to assess specific subjects of health literacy, mental health literacy (N = 3 ‒ 34,35,41), and oral health literacy (N = 2 ‒ 40,43). These results emphasize the lack of instruments to assess health literacy in specific contexts of disease, such as chronic conditions or non-communicable diseases with high mortality rates in the world, Portugal not being an exception 46.

Regarding the aims of the study, we consider two main categories: one regarding the development of new measures, exclusively designed to meet the characteristics of a specific group of the Portuguese population, and another one that is focused on the adaptation of measures previously developed in other countries. As already stated in the results section, the majority of the publications (N = 12) are dedicated to the adaptation of existing measures 23,30-34,36,37,42-45, and only 5 publications are dedicated to the development of new measures 35,38-41. Regarding the aims of the study presented in the publications analysed, some publications (N = 4) also specify as an aim the study of psychometric properties and the assessment of health literacy levels (N = 5). So, the publications that were considered for this review were not exclusively dedicated to the development or adaptation of health literacy measures.

This point is quite relevant. On the one hand, the adaptation of existing measures allows the comparison and correlation with other studies, for instance, with similar studies, and always considering the necessary limitations on generalizations 47. On the other hand, the use of translated or adapted versions of existing measures could not reflect the whole social and cultural context where the adapted instrument will be used. So, it is necessary to consider the advantages and disadvantages of using an existing tool or developing a new one, which is a time-consuming process, bearing in mind the goal and the target population of the study and what is intended to be achieved to deepen the knowledge in this field of research.

Regarding the dimensions and domains that each instrument used to measure health literacy, the analysis revealed some diversity. The majority of the publications analysed are focused on one or more basic skills such as comprehension (that includes reading and writing), pronunciation and numeracy 32,33,37,42-45, and more advanced skills in communication and use and application of the information 23,30,31,36,38-40, concerning not only general health literacy but also mental health literacy 34,35,41. As a multidimensional construct, health literacy measures that were analysed in this review show that there is not a single instrument that can assess health literacy in all domains and dimensions which is itself a limitation. The selection of an instrument will rely on different aspects that meet the study aims, but each instrument should match the health literacy definition from which it is derived 10.

The studies analysed revealed that 13 out of 17 23,32,33,36-45 have a young adult and/or adult population as the target of the instrument compared to publications 31,34,35 that targeted adolescents and/or young adults. This result evidences that there are no validated instruments available to measure health literacy in other groups such as children, the elderly, or patients with chronic diseases, neither regarding general health or disease-oriented literacy. Children and adolescents are an important target of health literacy skills because they are active learners in a phase of transformation and building, so it will be easier to see a change in their attitudes and behaviours regarding health if they improve their health literacy 48,49. The elderly are a vulnerable group that is more likely to use healthcare services as well as patients living with chronic diseases; thus, health literacy plays an important role in improving the access and use of healthcare 50,51. Instruments targeted to these specific groups can be important tools to design tailored and impactful interventions such as chronic disease management.

The publications analysed also show that only 1 study covered the entire Portuguese territory (mainland and the autonomous regions) 23 and 3 other studies covered Portugal’s mainland 30,36,37 which suggests that generalization of the results and the extensive use of tools in Portuguese population has to be carefully conducted. Regarding reliability and validity which are crucial for the quality of the publications reviewed, the results available evidence that the studies that reported internal consistency and construct validity are reliable and valid. However, the heterogeneity and specificity of the instruments require the use of different methods and measurements to ensure reliability and validity. Moreover, the publications analysed, when necessary, point out the limitations and are referred to further steps to improve the quality of the analysis performed.

Limitations and Further Recommendations

As already stated, this review intends to present the current scenario on health literacy measurement in Portugal; however, some limitations should be considered. Only 6 out of 17 publications 32,33,37,41,42,45 analysed have the instrument fully available, which is important to carry a more accurate and specific analysis of the full content of the instruments. The non-identification or at least the partial identification of the items does not allow an accurate assessment of the construct and how it is operationalized.

It is also important to refer as a limitation that there are several instruments and tools developed or adapted to measure knowledge about different diseases that were not included in this review because they only refer to knowledge and not to the other skills that integrate, for instance, the different definitions of health literacy. The most common ones are diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, or cancer 52. These instruments cannot be used per se to measure health literacy itself, but their inclusion would allow broadening the scope of this work as knowledge is an important dimension of the health literacy construct.

Another limitation of this study is the assessment and characterization of health literacy levels that were not addressed in this review. The analysis of health literacy levels that were performed in several publications that were included in the analysis would be an important indicator to broaden the knowledge on low or limited health literacy regarding the different constructs of health literacy that are used in the different instruments that are validated to be implemented in Portugal.

These results obtained in this review address further recommendations to improve the Portuguese context of health literacy research. It highlights the need to develop and/or adapt health literacy measures focused on specific diseases or disease-oriented which will be an essential asset to improve health literacy and consequently health outcomes, e.g., in non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, diabetes, asthma, and other respiratory conditions.

There is also an evident need to develop or adapt instruments to evaluate health literacy, and general or disease-oriented measures in specific groups of the population, for instance, in children and adolescents as well as in the elderly. At last, the contexts, settings, and target groups where these instruments can be used should be a key point of the studies.

General measures are more suitable for comprehensive studies that can be carried out longitudinally, not only on individuals but also on population-level providing insights on the evolution of health literacy levels and how interventions should be shaped. Specific settings and target groups should also be a priority, so disease or condition-specific instruments that can be used in clinical settings are more adequate, e.g., to design and implement interventions in patients to help to cope and manage chronic diseases 53. This is the first review report on health literacy measurement in Portugal, as far as the authors know now that evidences the important achievements that have been made in health literacy measurement in Portugal as it is analysed here; however, there is still room for improvement, particularly which refers to the focus of the instruments, the settings, and its target groups.

Conclusion

This first review on health literacy measurement in Portugal shows that this is a recent field, with studies related to health literacy measurement starting to be published in 2014. Despite the recognized evolution in the last decade regarding the development and implementation of several instruments and tools that allow portraying the Portuguese reality on health literacy, there is still a long way to implement systematic studies that will produce a robust core of data. A nationwide consistent strategy is critical to understand the needs and barriers and propose innovative solutions to improve national health literacy practice.

There is evidence that this field currently faces high fragmentation making it difficult to acknowledge what and how has been developed and achieved, and this has negative consequences for the crucial articulation of scientific knowledge with professional and “laypeople” practices. There is a need to promote collaboration between researchers across institutions and between researchers and health educators, most of the time health professionals. The exchange of results and practices could contribute to reducing redundancy (e.g., development or adaptation and validation of the same tool by different researchers) increasing our knowledge in this field, and being more efficient and less time and resource-consuming.

In sum, this study presents the first general overview of health literacy measurement in Portugal and clearly shows that to deepen our knowledge of health literacy in different groups of the Portuguese population it is essential to broaden the scope and the target of health literacy assessment to have a comprehensive understanding that will allow transforming our reality regarding health and disease. As a determinant of health, health literacy must be a priority in health policies and systems, especially when dealing with unique challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Prevention is the key to overtaking current and future global health emergencies with populations’ health literacy playing a crucial role.