Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry defines persons with special health care needs as those who have any impairment or limiting condition that requires medical management, health care intervention, and/or use of specialized services or programs 1. Impairments or conditions may be developmental or acquired and may require modifications in the provision of adequate care in dental settings 2. Persons with special health care needs have an increased risk of poor general and oral health and have a high prevalence of oral diseases throughout their lifetime 3,4. Moreover, patients with special needs are among the most underserved population groups, primarily due to ongoing issues with access to care 5,6. Dental health is the most common unmet health care need for children with special needs 7.

Until recently, the dental management of patients with special needs who have developmental conditions was accepted as the purview of the specialist care of pediatric dentists using either conscious sedation or general anesthesia, as part of interprofessional teams involving medical specialists such as anesthesiologists. In 2004, the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) issued a new standard for the training of dentists and dental hygienists in the USA. This standard states that professional programs must ensure that graduates of such programs must be competent in assessing the dental treatment needs of patients with special needs 8. In a review of US dental schools, following this change in standards Clemetson et al. 6 investigated the changes required of US dental schools to ensure the fulfilment of the CODA standards. Many surveyed schools (80%) stated that more time was required to teach students how to treat special needs patients.

Robust didactic and clinical curricula, in which students are trained both theoretically and clinically, to treat and manage patients with special needs can positively affect the preparedness and comfort level of dental graduates in subsequently managing such patients 9,10. This is due to dentistry being an experiential field that requires not only knowledge but chairside skills that can only be gained through the clinical training of undergraduate students.

The comfort level and preparedness of graduates can mitigate the large unmet dental needs associated with such patients as the burden of care is then shared between specialist teams and well-trained general dental practitioners 11. While US dental schools have made strides toward enhancing curriculum in special needs dentistry, underpinned by mandates in accreditation standards there still exist differences in the levels of clinical exposure to and management of patients with special needs in international dental schools 11,12. Alumran et al. 13 in a review on the preparedness of dental graduates in Saudi Arabia to treat patients with special needs discussed a lack of education and clinical training at the dental undergraduate level, which may result in hesitation to treat this group of patients by dentists upon graduation.

Trinidad and Tobago is a twin-island, English-speaking, state located in the Caribbean comprising a population of 1.4 million, of which 52,243 persons live with a disability 14. As the only school of dentistry (SoD) on the island, which provides training for local and regional students, training in special needs dentistry is included in the competency-based curriculum. Didactic components are included in courses in gerodontology and special needs in the fourth year of training as well as pediatric dentistry that students receive in the third, fourth, and fifth years of training. In year 4 of clinical training, students rotate through a stand-alone special needs dental clinic. Students are exposed to the clinical management of special needs patients once weekly in blocks of 3 hours. At this clinic, students observe, assist chairside, or treat patients who have physical, mental, developmental, and cognitive disabilities and those who are also medically compromised such as oncology patients. Students in the fifth year are encouraged to comprehensively manage patients with physical disabilities in the general clinics of the SoD. Interns spend a 6-week rotation in the special needs dental clinic as part of their postgraduate clinical training in general dentistry. Finally, not-for-credit elective courses are run throughout the year in sign language to facilitate communication between deaf-mute patients and dental students in the dental clinics.

This study aimed to examine the knowledge and attitudes of dental students at the University of the West Indies, SoD, toward the treatment of patients with special needs. An interrogation of these attributes of students within the program could give insight into the shortfalls of the curriculum. Dental curricula must be robust in providing training and clinical experiences for all types of patients, inclusive of patients with special needs as part of developing clinical competencies.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University’s Ethics Committee (University of the West Indies, St. Augustine Ethics Committee, CREC-SA.0139/12/2019), and written consent for the study was obtained from each participant. The sampling frame for the student population in this study comprised all students in the clinical years of dental school (years 3, 4, and 5) as well as those completing a 1-year postgraduate clinical training in general dentistry (dental internship) at the University of the West Indies, SoD, St. Augustine (UWI-SoD).

A modified version of a previously validated survey instrument was used - Dental Students Attitudes’ Towards the Handicapped Scale (DSATHS) 15. The terminology “handicapped patient” was replaced with “patients with special needs.” A face validity exercise was completed to assess the appropriateness of use in the local setting of this modified instrument. The instrument, composed of 20 closed-ended items, explored the themes of demographics, educational experiences, and personal attitudes. Five out of the six items on the instrument utilized negative attitudes. Respondents answered along a 5-point Likert scale (highly disagree to highly agree) for the latter two themes. Statistical analysis of data was performed using the program “Statistical Package for Social Sciences” (Version 27; IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Frequency distributions were used to analyze data. Responses were generally aggregated into disagreement (highly disagree and disagree) and agreement (highly agree and agree). Crosstabulations and likelihood ratios were used to examine attitudes between different year groups at an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

There was a response rate of 85%, with a total of 102 clinical students and interns returning completed survey instruments. The mean age of respondents was 25.23 (SD ± 3.784). Most respondents (81.4%) were female. The largest group of respondents (34.3%) were in their final year (year 5), 20.6% were interns, 17.6% were in their fourth year, and 27.5% were in their third year.

Educational Experience

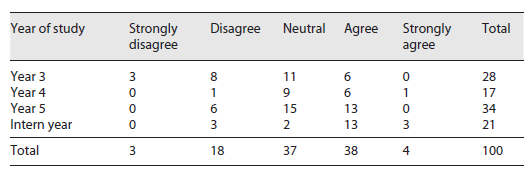

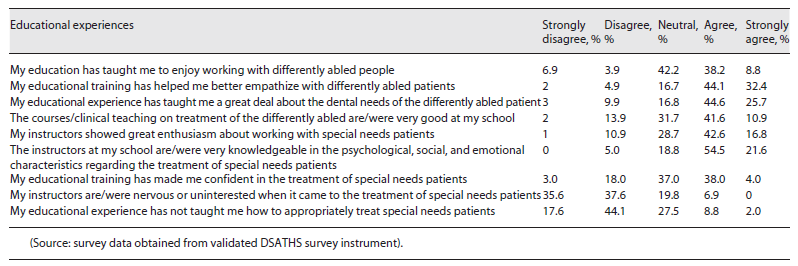

Table 1 gives a synopsis of the descriptive statistics associated with educational experiences. The majority (76.5%) of participants generally agreed that their educational training helped with empathizing with patients with special needs. Most (69.6%) of the participants agreed that their education had taught them about the specific requirements of patients with special needs. Almost half (52%) of the respondents agreed that the quality of teaching provided on managing special needs patients, by lecturers and instructors at the SoD, was good. Less than half (41.2%) of respondents believed that they were confident enough to treat patients with special needs on graduation. When likelihood ratios were used between cross-tabulated items on the educational items (Table 2), there was a statistically significant association between the year group and the confidence to treat special needs patients (p = 0.001).

Table 1 Primary data showing frequency distributions of perceived dental educational experiences regarding patients with special needs

Personal Attitudes

Generally, the personal attitudes of the surveyed respondents were good concerning special needs persons and associated dental management (Table 3). Only 18.6% of all respondents agreed that special needs patients should only be treated by specialists and 23.5% agreed that special needs patients needed to have dental treatment in a hospital setting only. An even smaller percentage (10.8%) indicated they were not interested in learning about the dental management of special needs patients. Conversely, 82.4% of all respondents indicated that they were concerned about the future dental treatment of special needs patients. There were no significances reported when gender was cross-tabulated with any of the items on attitude. When crosstabulations and likelihood ratios were used to look for significant associations between year group and attitudes, none were found to be statistically significant except the item dealing with the provision of care to patients with special needs by specialists only (p < 0.001). Interns (95.2% of intern respondents) disagreed that dental management of patients with special needs should be carried out by specialists only (Table 4).

Table 3 Primary data showing frequency distributions of personal attitudes toward patients with special needs

Discussion

Current country-wide statistical information for Trinidad and Tobago is devoid of the relative types of disabilities or special needs patients in the local population. This is important since not all persons with disabilities require special health care 16. Special needs dentistry is defined as “a speciality concerned with the oral health care of patients with special needs for whatever reason including those who are physically or mentally challenged” 17. It has been shown that most persons requiring special care dentistry should be able to access treatment in a local, primary care setting 18. Only patients with severe cognitive impairment may require general anesthesia sedation for dental management. It is important for dentists graduating from dental school to understand the role they can play in the management of such persons.

Overall, only 41% of the surveyed students felt confident enough to deal with patients with special needs upon graduation. This the authors attributed to the amalgamation of all the respondents at various levels of training - both didactic and clinical among the students. Interns who primarily complete clinical training and have a dedicated rotation of special needs care generally agreed (76.2%) that they were confident to treat patients with special needs. This contrasts with only 21.4% of third-year students who agreed to be confident to treat such patients. The favorable attitudes of the respondents in this study are in keeping with the work of Holzinger et al. who assessed the attitudes of dental students concerning patients with special needs before and after a didactic course in special needs dentistry in the fourth year of training 2.

The UWI-SoD didactic and clinical training in the management of special needs patients is ongoing from the third year to the internship. This didactic component of education, starting in the third year, aids in the preparation of students for clinical training; however, the clinical component is imperative to ensure confidence to treat this population of patients upon graduation. Reinforcement of clinical experiences is particularly relevant when developing competencies in managing patients with special needs 19. Further, dentists have cited inadequate experience with patients with special needs as a reason for them being unable to treat this group of patients upon graduation. This underscores the need to have clinical training for undergraduate students with patients with special needs 20.

Attitudes or the mental stance of students in dental education is important since they form an important feature of professional life and the metamorphosis of students into professionals is dependent on the changes in attitudes of students 21. This is consistent with the findings of Dao et al. 22 where when dental education in the field of special needs dentistry was taught at the undergraduate level those dentists were more likely to provide treatment for this special group, compared to those who were not educated to treat patients with special needs.

While changes in attitudes could be purposefully brought about by working on beliefs, thoughts, and feelings, increasing knowledge, deepening understanding, and improving levels of technical competence can also cause positive shifts in student attitudes in professional programs such as dentistry 21. Frequent, continuous, and cumulative exposure to such patients, throughout clinical training, may have had a positive overall effect on the personal attitudes of students. This augurs well for the curriculum at the SoD since clinical exposure to special needs patients during dental training is inadequate in many international dental schools 11,23,24.

Limitations

While the results of this study provided useful insight into the perceived educational experiences and attitudes of students at the SoD, there are concerns about external validity due to the non-probability sampling framework - a small population at a single dental school - used in this study. Also, the results of this study are static and only represent a limited snapshot of the perceptions of educational experiences and attitudes of dental students. These drawbacks make the findings of such research not broadly generalizable, but it provides useful insight into how curricular changes can be affected to bring about improved attitudes of dental students in dealing with patients with special needs in a Caribbean setting.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, the authors would recommend earlier exposure of students to patients with special needs in the clinical curriculum. Third-year students are introduced to the clinical management of patients in the second semester of the third year. At this time, they can be initially introduced to patients with physical challenges such as blind, deaf-mute patients, older, or medically challenged patients. As clinical training progresses, they can be introduced to patients who have more complex challenges where behavior management techniques or sedation can be utilized. Additionally, the authors recommend that students and interns be strongly supported to comprehensively manage patients with special needs within the competency-based curriculum framework. Such comprehensive patient management strategies should include preventive treatment which can reduce the incidence of future oral disease and the associated burden of care.

A curriculum that includes both didactic components and increased clinical exposure to patients with special needs during undergraduate dental education may lead to an improvement in the attitude of dental students as well as their confidence in treatment. Increased time and clinical exposure of dental students to patients with special needs increase confidence and the future likelihood of treatment of this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Steven Moore and Professor Giuliano Pereira de Oliveira Castro of the Universidade Federal de Goiás, Brazil, for assistance with the translation of the abstract into Portuguese.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Approval Number: CREC-SA.1039/19/2019. Written informed consent was gained by all respondents before they participated in the study.

Author Contributions

Trevin Hector and Shivaughn M. Marchan conceptualized the research, completed the initial literature review, and collected data. Shivaughn M. Marchan and Ramaa Balkaran submitted the proposal for ethical approval. Author Shivaughn M. Marchan completed the statistical analysis. Ramaa Balkaran provided the initial draft of the written work. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final draft of the work.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this work can be found at Harvard Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VZ8SBL.