Introduction

During the fourth month of 2020, the Latin American region was ranked as the epicentre of COVID-19 infections globally, aggravating the already existing inequity and precariousness in healthcare in most countries 1. The pandemic has been a threat to children and youth in Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC), affecting their correct development; one of the reasons is the decrease or alteration of protection programs and the increase in other diseases under control 2.

The marked social inequalities in the region and the weakened health services in some countries have hindered the effective implementation of containment measures, which has been reflected in high infections, added to the chronic diseases present in the regions like obesity, which further complicates a good prognosis for many infected 1. Due to the containment and control measures of the pandemic, children and young people have lost spaces of protection and interaction, such as schools or parks, among others, which has led to the detriment of their physical, mental, and socio-emotional well-being 3. Children and young are mainly considered vulnerable populations and sensitive to sudden changes, mainly in less favoured countries 4.

Years will be necessary to correctly assess the impact of the pandemic on the mental health of children and young people, even if the virus diminishes its power and strength, the damage to family stability, school failures, the lack of resources to maintain services, the experience of living more than 2 years with negative emotions, make medium and long-term sequelae not only in those infected but in all spheres of life in which children and young people live and develop. Sixteen million adolescents live with some mental disorder in LAC; suicide is also the third cause of death 5.

It is essential to know how the coverage of child services has been disrupted during the pandemic because when schools and public spaces are closed, children and young people have been at home for a long time, a place where they do not necessarily have the necessary nutritional support and environmental tranquillity, added to the increase in violence and aggression suffered in some homes during the pandemic 6-8, for which social assistance becomes more relevant.

Faced with this adverse scenario, our main objective was to identify which protective factors could be associated with the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 and to determine its dynamism with the secondary aim of highlighting them as social resources in a health crisis as the pandemic for a vulnerable population such as children and young people. Since these are subsequently derived in hospitalizations and deaths. Like most of the world, Latin America has registered cases in children under 14 years of age, which seem few compared to older age groups but are relevant since the child and youth population have been indirectly receiving the strongest impact of the pandemic. Ensuring protection for this age group is essential; these are the key questions that will be addressed in this study.

Methods

This is an ecological study of 10 LAC countries to study protecting children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. The countries were selected due to the important variations among them in incidence for this age group and the availability of updated data.

Data sources

Global Health 50/50; Covid-19-project, from University College London, the African Population and Health Research Center, and the International Center for Research on Women 9.

Ourworldindata.org; dataset uses updated official numbers from governments and health institutions 10.

School Closures Database by income and region downloaded from UNICEF. The definition of school closure aligns with UNESCO's methodology 11.

World Bank 12.

Ministry Of Health and Wellness of Jamaica 13.

Monitor the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women and children, UNICEF 14.

The government Effectiveness Index refers to aggregate and individual governance indicators 15.

We used as outcomes the coverage of protection programs and services for children and adolescents during three time periods during the pandemic (Coverage of programs on social service visits, helplines, mental health, psychosocial assistance, and violence prevention); and the confirmed cases of COVID-19 by 100k, <14 years; last report (Jan 2022).

Predictors

School closing weeks by country are calculated by the number of students from pre-primary education to upper secondary education per region/globally based on March 2020 to November 2021.

COVID-19 stringency and Health Response index, which is based on policies response metrics (Cancel public events, restrictions, close public transport, public information campaigns, stay at home, restrictions on internal movement, international controls, school recommendations, testing, contract tracing, face coverings, vaccination, workplace closures: rescaled from 0 to 100 (100 = strictest)).

Healthcare access score 2021, 0 to 100 (100 better performance).

Rapid response score (rapid spread mitigation), 0 to 100 (100 better performance).

Early detection score 2021 (early detection and reporting epidemics), 0 to 100 (100 better performance).

Public health vulnerabilities score 2021, 0 to 100 (100 better performance).

Statistical Analysis

Coverage

To describe whether the coverage of programs and services for the protection of children and adolescents in the ten countries have been maintained, decreased, or increased during the pandemic, we only used the indicators referring to children and adolescents, not those of their parents; and according to the coverage percentage was reported, was attributed a value symbol as follows: ? - increase; ? - reduction; ? - without changes; ? - not applicable or uncertain. The first period compares to pre-COVID status, the second compares to 30 January 2020, and the three corresponds to pre-COVID level.

Correlation Analysis

We were interested in the relationship between the maintenance of coverage of protection programs for children and adolescents during school closure. There is a lack of face-to-face classes and being at home.

Using the information from the previous coverage analysis, a new variable score was proposed where if the program had increased, it was given a value of 3; if the program did not change a value of 2; if it decreased a value of 1; and if it did not apply or was uncertain a value of 0. The score was elaborated using only period 3 (Oct 2021). The Pearson correlation test with significance was used to analyse this correlation with the number of weeks of total closure of educational places during the pandemic until October 2021.

Multiple Linear Models

A multiple linear regression model was fit to evaluate the relationship between confirmed cases by 100k of COVID-19 (0-14 years population) and the performance of the countries and some key indicators like stringency index, healthcare access, rapid response, and early detection and public health vulnerabilities (Brazil and Uruguay were not considered in this sub-analysis because they did not report data on cases in the age group studied). The model’s adjustment variables were selected considering correlations patterns and their possible relationship with cases plausibility within a context where there are few studies on the topic (other health systems variables were considered and tested previously, but due to their low correlation and data availability, were not included in the final model).

The model shows (F test p = 0.009; adjusted R-squared = 98.7%), VIF = 4.9, and the residuals testing (Shapiro-Wilk test >0.05) for all variables. The analyses were performed with Stata (StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15.1. College Station, TX, USA: StataCorp LLC).

Results

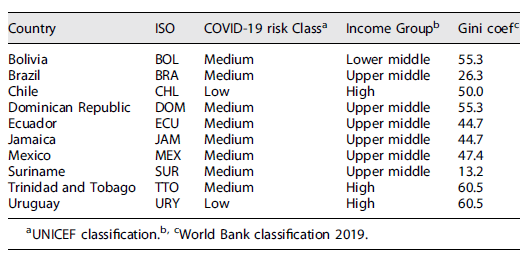

The sample characteristics are presented in Table 1; ten countries are under investigation from LAC understudy, with four economic levels, risk classification for COVID-19, and Gini coefficient. Most countries are classified as the medium risk for COVID-19, upper middle income, and variation in the Gini coefficient.

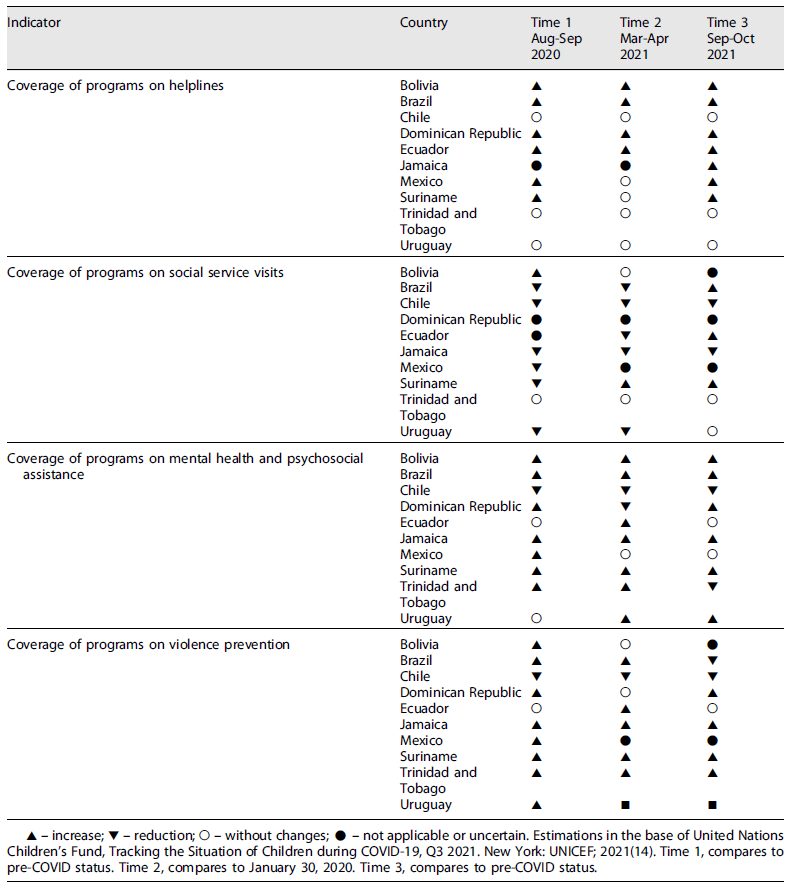

Table 2 describes the four child protection indicators by country. The symbols of these increased due to the pandemic, decreased, remained the same, or are uncertain during the three time periods since the pandemic’s start. Regarding the coverage program of helplines for children and adolescents, we highlight that except for Jamaica, all countries reported active coverage in the 3 time periods without changes or an increase. Bolivia, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador reported a similar rise in all three time periods.

There is an alternation between increases and decreases regarding the social service visits program coverage. Brazil and Chile stand out, where a reduction in coverage was reported in the three period-times, and Trinidad and Tobago did not report changes in coverage in the three periods (Table 2).

Regarding the coverage of mental health and psychosocial assistance programs, we highlight that all the countries have active programs in the 3 time periods; Bolivia, Brazil, Surinam, and Trinidad and Tobago reported increases in the three periods (Table 2). Finally, regarding the coverage of protection programs against violence, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago reported an increase in all three time periods; there is variation at different times for the other countries (Table 2).

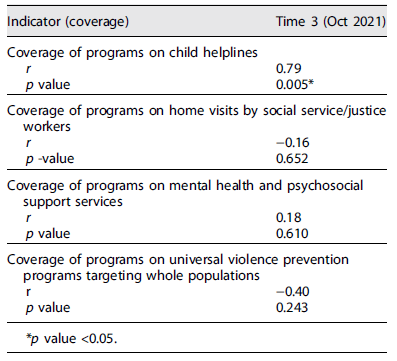

Table 3 shows the correlation between the coverage of the protection indicators and the number of weeks of schools completely closed during the pandemic. We highlight the strong and statistically significant correlation (r = 0.79; p value 0.05) between the increased coverage of child helplines and a greater number of school closures.

Table 3 Correlation between proposed coverage score of protection indicator and number of weeks of schools closed (n = 10 countries), 2021

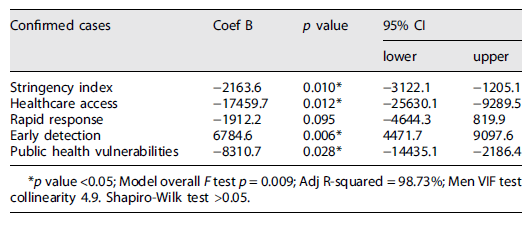

Regarding the multiple linear regression analysis (Table 4), we highlight the association between confirmed cases by COVID-19 and some predictors; cases and stringency index with a coef B = -2163.6, [CI -3122.1-1205.1]; p value = 0.010. Cases and healthcare access with a coef B = -17459.7, [CI -25630.1-9289.5], p value = 0.012. Also, the association between cases and public health vulnerabilities with a coef B = -0.8319.7, [CI -14435.1-2186.4]; p value 0.028.

Discussion

This study presents an approximation of ten countries in LAC in terms of coverage of child protection programs, COVID-19 incidence, and possible factors associated, with children and young populations from 0 to 14 years of age during the COVID-19 pandemic across an ecological framework.

The COVID-19 pandemic began as a health crisis in LAC but is now considered a humanitarian crisis 16. We found substantial differences between countries and variations in protection coverage for children and young people, the performance of health services, and their relationship with confirmed infections.

To highlight the scarcity of public information available on the status of minors during the pandemic, few updated reports on mortality, morbidity, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions for COVID-19 in minors in the countries of the region show the great lag in health monitoring in LAC 17. We have considered the countries that have reported information on coverage of programs for children and adolescents during the pandemic; it is striking how difficult it is to find data for this age group in Brazil, Uruguay, and Bolivia.

The Gini coefficient of the countries studied shows great income inequality in LAC. This region has been hit hard by the global economic crisis that has impacted poverty and precariousness 18,19. Violence prevention programs, telephone support lines, mental health, and social services are essential for the well-being of children and young people during the harshness and multiple changes in their lives throughout the more than 2 years of the pandemic.

In LAC, each country has prioritized the coverage of its programs in different ways throughout the pandemic stages 20. Ideally, these programs should have been increased or maintained during the pandemic, but the results show that this was not necessarily the case and that the coverage was sometimes reduced (Table 2). This could indicate that coverage was prioritized for older age groups with more significant comorbidities, affected to a greater extent by the virus, or due to failures in welfare services for minors.

The correlation analysis focused on the logic that the higher increase or maintenance of coverage of protection programs during the pandemic, the better, since minors due to closed schools would need that support and accompaniment more than before since they would lose a safe space with benefits such as educational centres. In the ideal scenario, it would be expected that the greater the number of weeks of closed schools, the greater the coverage of the protection programs should be. This was only true for the helpline programs, with a high and statistically significant correlation (Table 3), different from what happened with the other programs where the correlation was low and even, as schools closed for longer, the protection programs will decrease; it is a sign of a critical problem in the safety and protection of this population. On the increase in the use of helpline programs, it is to be expected that the telephone guidance lines have been used more due to the limitations of movement. However, the most relevant thing is that most of the countries studied made available and expanded this resource, which was essential not only in terms of young people’s concerns about their physical health or their families but also their mental health. The form of use of this resource varies from person to person and will surely be the subject of future research. Still, the essential thing is that it is an effective use that is real support, especially in times of real crisis, as it was for young people during the pandemic. A health system can offer much if the helpline resources are optimized and expanded 21.

Regarding the closure of schools and their relationship with confirmed cases, it is now possible with robust scientific accuracy to indicate that educational centres are not and nor were niches for uncontrolled infections and that adults transmit the virus to children more than children to adults; in many scenarios and countries, the closure of schools was applied more as an empirical measure than based on solid scientific evidence 22-29.

The regression model (Table 4) shows us that containment measures, access to healthcare, and public health vulnerabilities in the countries studied are statistically associated with the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19; that is, the higher the score and performance in these indicators, which indicate better performance, the fewer cases of contagion in this age group. This information is very relevant to preventing current and future pandemics. Also, the higher the score in the rapid response, the lower the cases of contagion, although this association did not show statistical significance. But something very relevant is the early detection indicator. The better the performance, the greater the number of confirmed cases, supporting the importance of surveillance systems and mass testing. Finally, we highlight the result on the public health vulnerabilities variable; it is also fundamental since the higher the country’s score in this variable, that is, the less vulnerable it is, the fewer cases of contagion, and this association is statistically significant (Table 4); all these estimates when adjusted for the other variables.

We must report some limitations; as this is an ecological study, we cannot ensure a causal association between the number of cases confirmed by COVID-19 and the predictors considered. One of the limitations that may also occur is that confirmed infection in children and adolescents is still not as common as in older ages. Therefore, there may not be enough variability to detect these associations.

Another possible limitation not only of this study but in general of all studies on COVID-19 that use the “Cases” as a variable is that the number of confirmed cases could be underestimated since it depends on the testing policies of the countries. However, the cases reported by governments are vital to understanding the virus’s transmission level and speed of circulation.

This study also has strengths, like the use of the stringency index in the multiple linear models 10, since despite being considered a guide to evaluating the measures on the spread of COVID-19 cases by country, it considers the nine most important actions that governments have implemented, from mobility and internal and external restrictions, among others, already detailed in the methods section.

Therefore, this study adds relevant evidence on the state and services that children and adolescents have during the pandemic; the scientific community and the health systems of the countries must not remain stuck in the initial trends of the virus; it is clear that the dynamism of transmission, containment, vaccination, vulnerabilities has changed and that will allow for guiding the actions of the health systems more precisely.

This study also obtains results consistent with other studies, where the closure of schools (not necessarily synonymous with protection), physical and mental well-being and government decisions are key to the safety of children and young people 30-33. We must not also forget two key points in LAC; the higher poverty has induced a faster spread of the virus 34, and the current scenario where the omicron variant has triggered infections in all age groups almost without control; fortunately, deaths have not skyrocketed to the same extent. Experts say other pandemics will come, and this emergency must be turned into an opportunity 35; it is vital to strengthen protection programs for the population, especially for vulnerable people, such as children and young people.

Acknowledgments

This paper was made possible with funds from the FCT e a Unidade de I&D CHRC - Comprehensive Health Research Centre (UI/BD/150908/2021).

Statement of Ethics

Databases are anonymous, guaranteeing data confidentiality. Our analyses were based on public available secondary data. An ethics statement was not required for this study type as it is based exclusively on data from public secondary data.