Introduction

Indonesia is facing a crucial demographic shift, with an increase in the number of older people (i.e., 60 years and over), transforming the demographic structure into an ageing population 1,2. Based on the 2010 population census, the number of elderly individuals in Indonesia was 18.1 million (7.6% of the total population), and it is projected that the number will increase to 33.7 million (11.8%) and 48.2 million (15.8%) by 2020 and 2035, respectively 2. In terms of life expectancy, Indonesia has made progress in prolonging the population’s life; however, the shifting age structure toward higher-age groups has led to consequences regarding the availability of health services for such populations, including healthcare financing and expenditures required 3.

The introduction of the universal health coverage insurance scheme in 2014 was another milestone regarding the government’s commitment to securing a healthcare financing system as a policy option that can help address the challenge of future ageing populations in Indonesia 4,5. This program has influenced the readiness of health services that respond to ageing populations. With a comprehensive benefits scheme that covers most outpatient and inpatient care, enlists public and private health providers, and has enrolled almost 225 million people (i.e., 85% of the total population) by the end of 2019, the program has significantly contributed to healthcare provisions for the majority of Indonesian people, including the elderly 5,6. However, the lack of long-term care facilities has also affected the access and quality of services, particularly in resource-poor settings such as rural and remote areas 7.

Currently, the increasing number of older adults in Indonesia has not been addressed by specific programs for the elderly. The healthcare system continues to focus on an agenda to address infectious diseases such as dengue fever, tuberculosis, malaria, and diarrhoea. Thus, resource allocations have not kept pace with the rising rate of non-communicable diseases (e.g., stroke, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and cancer) among older adult populations 7, 8. Moreover, the Indonesian social insurance program, which is intended to cover all populations, is not designed for an ageing population 7,9. The lack of a sufficient healthcare system based on a community setting increases the vulnerability of the elderly to poor health and quality of life, mostly due to the threat of chronic illness from non-communicable diseases, and the lack of financial support for accessing quality health services, especially in rural areas 5,10,11.

Healthcare services for elderly populations in Indonesia have been arranged in both institutional and community services 12. Residential aged care homes or social nursing homes managed by the government and private nonprofit institutions are institutional services that are mostly available in urban areas 13. However, only a small number of elderly individuals reside in this residential aged care home setting because of cultural norms in Indonesian communities that support elder adults living with their families 13. Private caregivers may provide care for older adults residing with their families; however, only upper-class families can afford this type of care 13,14. For other rural families, providing healthcare for older adults in their care is challenging due to limited resources 7,15. Community health centres that offer primary healthcare providers access to healthcare providers for rural populations, and about 10,134 community health centres spread all over Indonesia in 2019 16. Community-based initiatives for health programs for community-dwelling elderly, also known as integrated health posts for the elderly (Posyandu lansia), are also available and accessible health programs 13,17. According to a Ministry of Health report, there were about 80,353 Posyandu lansia in Indonesia in 2017 18. Poor health infrastructure is still the main constraint; however, rural communities have the adequate social capital to deal with restrictions, for example, through initiating community participation for providing Posyandu lansia by using their resources 15,19. With a higher proportion of elderly individuals (57%) in rural areas as opposed to urban areas 2,15, it is important to explore the existing implementation of healthcare services for elderly populations in rural Indonesia to shed light on appropriate policy interventions.

An initial preliminary search had been conducted to identify similarities in the literature review topic through several sources such as PubMed, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), the Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, and the Cochrane Library, and there were no literature review studies either published or underway that considered this from the perspective of implementing healthcare for community-dwelling elderly in rural areas. Therefore, this systematic review was aimed at identifying and synthesizing relevant evidence in Indonesia regarding the barriers and enablers of healthcare services for this population.

Methods

The review was conducted following the JBI methodology for qualitative evidence synthesis by using a meta-aggregative approach 20,22. Meta-aggregation concentrates on the original syntheses from findings of individual studies to generate cross-study generalizations that lead to recommendations for practitioners and policymakers 22. Even though the meta-aggregative approach reflects the processes of quantitative review, it is sensitive to the nature of qualitative research and its tradition 20. Meta-aggregation aims to balance the complexity of the research material from original qualitative studies with the utility of outcomes for practical action 21. The process of synthesis is provided as follows.

A search was conducted using the following electronic databases: PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL, by employing keywords and index terms. Keywords related to the topics of “health services,” “health care,” “elderly,” “older,” and “rural area,” with the geographical notion “Indonesia,” were applied to facilitate the search strategy of articles. Moreover, the review was limited to the published studies in English from 2010 to 2020.

Participants were elderly individuals with their families, health volunteers or cadres, community members, village administration officers, and healthcare providers (i.e., health staff, midwives, etc.). The review included studies that focused on healthcare services in Indonesia for rural-dwelling older adults related to health promotion, prevention, and clinical care. The phenomena of interest were participants’ perceptions of enablers and barriers based on their understanding, experience, beliefs, and aspirations in the context of healthcare for elderly populations. Qualitative studies with a clear description of methods and results were included. In addition, mixed-method research studies that comprised a qualitative component were also included. Unrelated studies that were not relevant to the subject matter of the review were excluded.

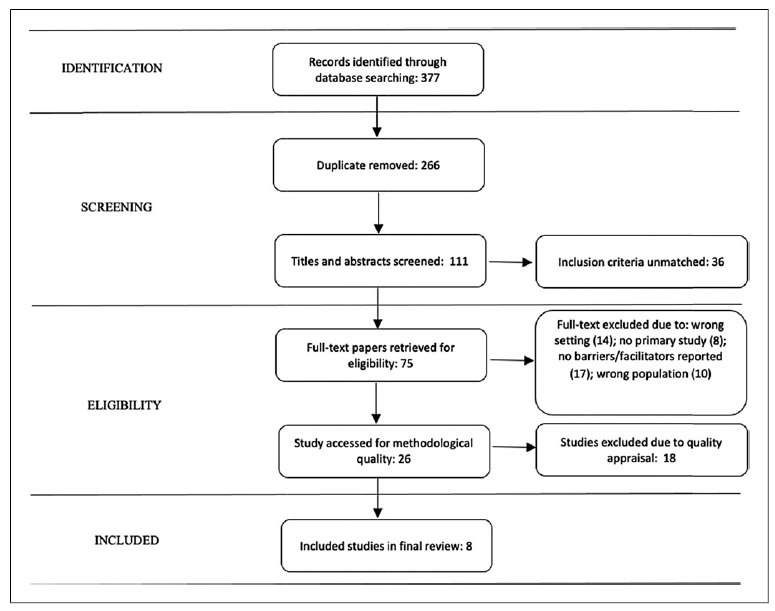

The procedure for article selection was conducted by two independent reviewers using the inclusion criteria of the study. Any disagreements between reviewers regarding each stage of the article selection process were decided through discussion and involved the third reviewer. This process was facilitated by applying the Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI) software 23,24. Overall, the article selection process was reported and presented by employing a flow diagram of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 25,26.

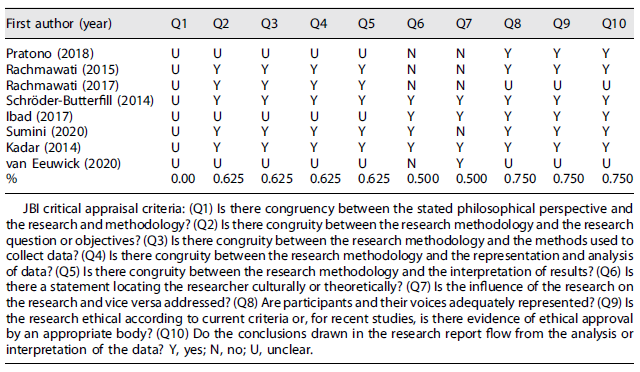

All relevant articles included in the synthesis were critically appraised for methodological quality by applying the JBI critical appraisal tool 21,22,27. This tool includes a 10-item standardized JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies and critical appraisal criteria 20. Then, the study findings of the articles were graded according to the ConQual approach for assessing credibility using three levels of evidence: unequivocal, credible, and unsupported. This also reflected the availability of reported themes in the articles through citations or interview excerpts 21,28. “Unequivocal” means that articles provide statements beyond a reasonable doubt. “Credible” means that statements are open to challenge and interpretation. “Unsupported” refers to a lack of directly reported evidence; thus, it should be read with caution.

A meta-aggregation approach was used to pool qualitative study findings, employing JBI SUMARI software 23,24. This approach synthesized study findings to create a set of statements reflecting the aggregation. The process was facilitated by categorizing study findings based on similarity in meaning. The resulting categories were then meta-aggregated to create a comprehensive set of synthesized findings. Then, these findings were used as a basis for evidence-based practice.

Results

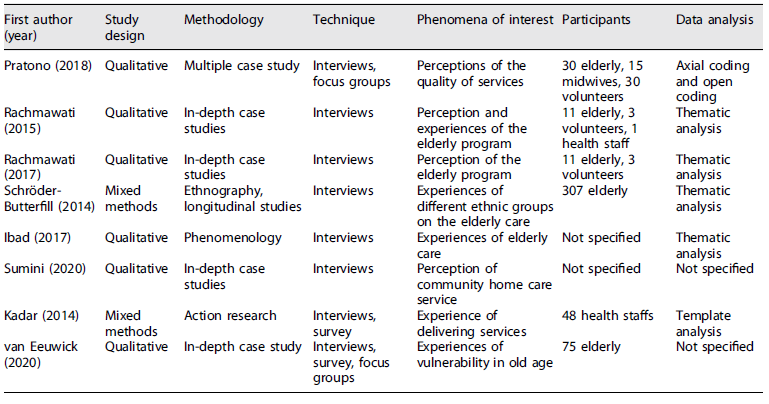

The initial search identified 377 unique citations based on congruency with the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Following the removal of duplications, the search strategy resulted in a total of 111 articles. Based on a review of titles and abstracts, 36 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. A full-text review resulted in the exclusion of 75 additional studies based on inclusion criteria. The remaining 26 studies were assessed for methodological quality, which resulted in the exclusion of 18 studies. The final sample for the meta-synthesis was 8 studies. A critical appraisal was conducted for the included article, which found that the quality of the articles was moderate, particularly due to the less adequate methodological procedure (Table 1). The characteristics of the studies are described in Table 2.

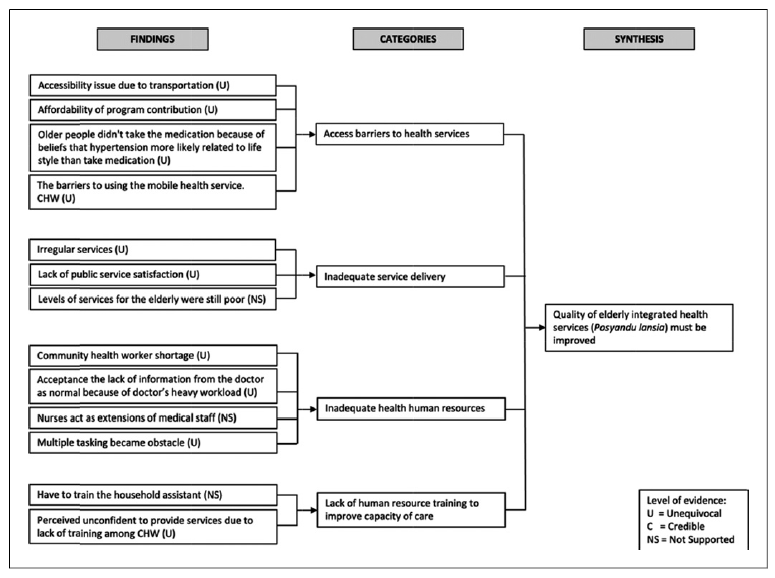

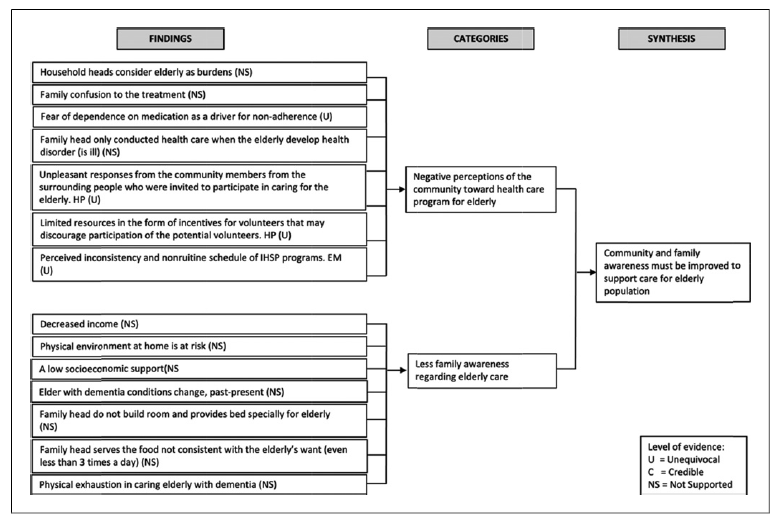

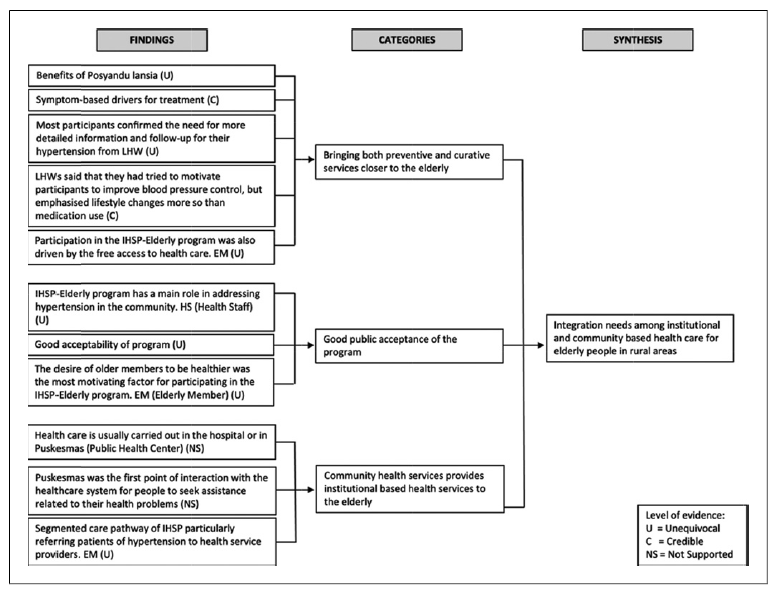

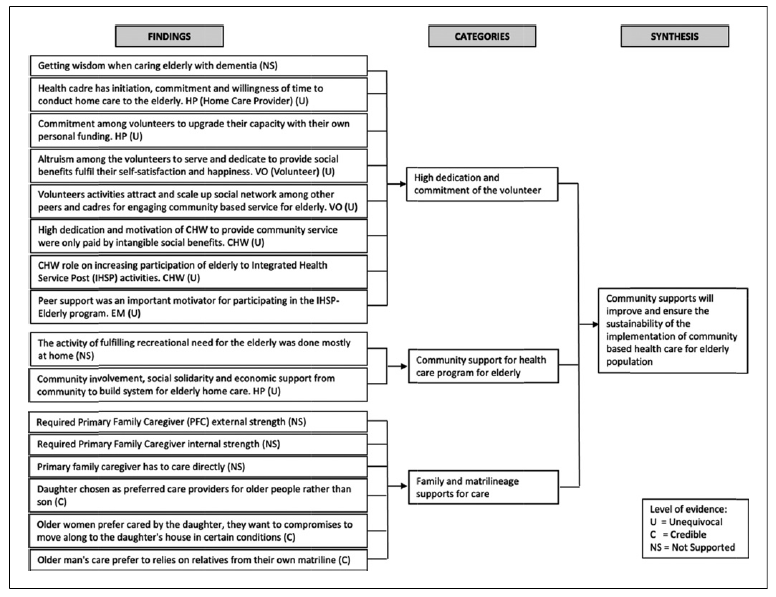

Fifty-four different findings were obtained and presented in the first column of Figure 2-5. The column offers specific information regarding the findings in the particular articles reported and also contains its level of evidence. Twelve categories were identified: (1) bringing both preventive and curative services closer to the elderly, (2) good public acceptance of the program, (3) community health services providing institution-based health services to the elderly, (4) access barriers to health services, (5) lack of quality services, (6) inadequate health and human resources, (7) lack of human resource training to improve the capacity of care, (8) high dedication and commitment of volunteers, (9) community support for healthcare programs for elders, (10) family and matrilineage support for care, (11) negative community perceptions toward healthcare programs for elders, and (12) less family awareness regarding elderly care. These categories (shown in the second column of Fig. 2-5) were then analysed to generate four synthesized statements (column 3 of Fig. 2-5) described in the following sections.

Fig. 2 Integration needs among institutional and community-based healthcare for elderly people in rural areas.

Fig. 4 Community supports will improve and ensure the sustainability of the implementation of community-based healthcare for elderly populations.

Synthesis 1: Integration Needs among Institutional and Community-Based Healthcare for Elderly People in Rural Areas (Based on Categories 1, 2, and 3)

Three categories explain the perception of health services among the elderly regarding institutional and community-based programs related to integrating services: (1) bridging services closer to the elderly, (2) elderly acceptance of programs, and (3) characteristics of institutional-based services in community health centres. These three categories indicate a positive response to elderly healthcare at the community level, with the additional expectation of unsegregated service provision 29,30. “Being examined is exciting, you know, as an elderly people, what a great opportunity we have to get an examination for free…” 30. “…Posyandu lansia merely provided basic health check-up, such as taking my blood pressure, asking some questions and weight to make sure whether they need to send me to the hospital for further tests…” 29. This synthesis also identifies the benefits of promotive, preventive, and curative blended programs for community-dwelling elderly in rural settings 31. “Belonging to the community provides benefits, such as health services once a month, religious activities, dancing, and recreation once a year…” 29. Medical support for home care visits and interventionist care is supported by health staff at community health centres 31,32.

Synthesis 2: The Quality of Elderly Integrated Health Services (Posyandu lansia) Must Be Improved (Based on Categories 4, 5, 6, and 7)

This synthesis reveals that the service quality of elderly integrated health services (Posyandu lansia) in rural areas should be improved due to several inadequate aspects of stewardship, resources, and service provision. The fourth category addresses the issue of barriers to accessing Posyandu lansia. As expressed by elderly participants, “the integrated services are for the elderly, but only a few of them can access the services. Those who stay nearby will be able to join the activities…” 29. “Elderly families here, sorry to say, can’t pay for the treatment and care because they’re still lacking in fulfilling the needs for daily food costs, especially to request home medical personnel…” 32.

The fifth category highlights several problems with service delivery. Irregular services and participant satisfaction have become challenging issues for long-term care services in Posyandu lansia. “It is not a routine program. If I am not mistaken, the last blood pressure checks other than the one today were done last month or 2 months ago. It would be lovely if they could make it weekly” 30. “I experienced delayed services and long waiting times. Sometimes, there were no paramedics and only some volunteers…” 29.

The sixth category identifies challenges in health and human resources. Limited resources cause inadequate support in delivering services to the elderly in the community, as described in the following quotes, “…We find it difficult to get volunteers for Posyandu lansia…” 29. “Sometimes we can’t do activities such as home visits because we lack health staff here in community health centres…” 31. “No, health workers didn’t tell me anything, there was no advice. I need more suggestions actually” 33.

The seventh shows the lack of training to improve care skills. As one community health worker clarified, “She (the other community health worker) did not come for a while… During that time, I could not take over her task (to measure blood pressure) as I am not skilful yet” 30.

Synthesis 3: Community Support Will Improve and Ensure the Sustainability of the Implementation of Community-Based Healthcare for Elderly Populations (Based on Categories 8, 9, and 10)

Three categories address enabler aspects that support the implementation of healthcare for elderly populations in rural communities: (1) dedication and commitment of volunteers to provide services to community-dwelling elderly, (2) social capital support for healthcare programs for elders, and (3) family role for proving self-care for their elderly, as exemplified by the following participants’ narrative: “I knew from the beginning that being a volunteer means that I’m not paid… It does not matter to me (not paid), it’s a kind of worship” 32. “Our village leader is very charismatic and powerful. We follow, especially when Posyandu lansia provided health information during the religious speech, and she encouraged all of us to participate in it…” 29. “With a daughter…I need not feel like a stranger, nor awkward about asking her to do my laundry or cook my favourite food” 34. “We have worked together with merchants and shops. We said, “If the elderly come to buy household needs like sugar and tea, please let them take it for free.” They know that elderly customers should not ask for money. Even the travelling meatball vendors, if they are in front of a senior’s home, they will give them a bowl of meatballs” 32.

Synthesis 4: Community and Family Awareness Must Be Improved to Support Care for Elderly Populations (Based on Categories 11 and 12)

This synthesis also highlights several constraints regarding the implementation of healthcare for the elderly in a rural area, such as the elderly being perceived as a family burden, a negative perception toward volunteers and their services, discouraging aspects of incentives, and less attention dedicated to caring for the elderly 29,32,35. For example, some participants stated, “Elderly families here, sorry to say, can’t pay for the treatment and care because they’re still lacking in fulfilling the needs for daily food costs, especially to request home medical personnel…” 32. “In my village, no one is interested in initiating the service. It involves much time and high-stress level…” 29. “They (community health workers) should be smarter than us, so they can give us solutions when we have health problems” 33. “Of course, there were those who refused. It was social work, and unpaid, so if they didn’t feel drawn to the issue, why would they do it? Taking care of the elderly…it was hard…” 32.

In addition, specific needs for the elderly regarding specific health conditions caused families to feel incompetent when attempting to provide adequate care 34,36. These categories constitute an overall synthesis regarding community and family aspects that should be improved to serve the elderly properly.

Discussion and Conclusion

The review has shown that the implementation of healthcare for community-dwelling elderly in rural areas faces several challenges and obstacles related to its service provision. However, enablers and facilitating aspects were identified, which support the success of its practice, particularly those related to community and social capital support. The barriers identified from this synthesis regard the problems, lack, and difficulties of implementing health services for the elderly in rural Indonesia. Conversely, the enablers reflected commitment, dedication, and public solidarity to facilitate healthcare for the elderly at the community level 29,36. The barrier and enabler issues related to the emerged synthesis findings from meta-aggregation are specifically discussed below.

Integration of Healthcare

Continuous and comprehensive health services from community-based care (Posyandu lansia) and community health centre to provide preventive and curative care were needed to enhance the performance of health services for elderly people in rural areas. Posyandu lansia already performs mostly promotive and preventive care that receives positive public acceptance. On the other hand, a community health centre, which has at least one location per sub-district, provides more professional healthcare, such as general practitioners, nurses, and other health staff, and offers extensive medical facilities for curative care, which older persons can access more easily. The arrangement of these two services was different and carried out separately. Posyandu lansia relied on community-owned resources and was run by volunteers. Moreover, it was supported by neighbourhood associations and village administrations. The management of Posyandu lansia was simple, and the services offered depended on the liveliness, creativity, and initiatives of volunteers or health cadres, as well as local community support and resources 29,32. Basic health check-ups like blood pressure checks, weight and height measurements, physical exercise, and health promotion activities became routine services provided by Posyandu lansia and volunteers. Elderly people who require medical attention are referred to the community health centre for further professional health treatment. The community health centre has a role as a gatekeeper for all healthcare services provided by general practitioners, dentists, and nurses. If patients need specialist treatment, they are referred to secondary facilities such as district hospitals, which have the capacity for medical speciality services. However, in terms of services, the community health centre is the nearest healthcare facility for elderly populations and is also the easiest to reach from their residences by using private vehicles or public transportation 37,39.

The integration of health services to provide elderly care, from Posyandu lansia to community health centre, must be improved due to differences in program management. The current integration is still in the form of a continuum of services from community-based to institutional care, where Posyandu Lansia conducts early screening and monitoring of diseases at the community level and the community health centre receives referrals of the elderly who need further treatments from Posyandu Lansia29. However, lack of coordination, ineffective communication systems, resource gaps, and geographical barriers became major issues of service integration 30, 40. Regional disparities regarding Posyandu lansia performance, such as quality, availability, and capacity of services, are also major challenges for health service improvement for community-dwelling elderly in rural areas.

Strengthening social capital by enhancing community capacity and volunteer capabilities with local government and sub-district administration support may be the key to the program’s success 33. The community health centre has an important role in providing guidance, supervision, and capacity building for Posyandu lansia through innovative models. The integrated, community-based healthcare approach to primary care that entails the collaboration of professional health staff and volunteers, or health cadres, may be possible. Home health assessment visits, mobile services, developing m-health and telemedicine, and integrated health hubs are examples of innovative models that have been implemented in both developing and developed countries to overcome disparities and fragmentation in providing healthcare for rural communities 41-44.

Quality of Services

The quality of community-based healthcare services for the elderly in rural areas must be improved due to the issues of access difficulties, irregular services, poorly maintained equipment, and lack of human resource competence. These occur as a result of a substantial shortfall in stewardship, resources, and service provision. Geographic isolation is a major issue among elderly populations who live in rural areas 45,47. Community outreach, such as Posyandu lansia, with its basic health service on one specific day of a month, might be the nearest healthcare that a rural elderly individual could have as part of their long-term care. However, due to their physical limitations, some elderly individuals also experience barriers to attending such services. In some cases, Posyandu lansia services are sometimes carried out irregularly, thus increasing the perception of the services being of low quality to the elderly 29. Moreover, limited resources that rely on community self-reliance have caused medical devices to not be properly maintained (e.g., problems regarding equipment calibration). Human resource competencies are another challenge due to the lack of capacity building 30. All of this makes Posyandu lansia the main outreach health service for the elderly in rural areas, and it needs significant improvement. The community health centre has a strategic role in empowering and supporting the Posyandu lansia program by involving other stakeholders such as village offices, NGOs, and people who are concerned about healthcare for elderly populations in rural areas.

Government policies about village fiscal transfers note that village governments have the authority to manage and provide their public services. This is an opportunity for Posyandu lansia to be developed with sufficient resources 48,49. Ever since the decentralization policy was implemented in Indonesia, the development of health services has undergone significant changes (e.g., the increasing number of Posyandu lansia per 1,000 citizens) 50. However, the progress varies due to different management capabilities and program priorities in various villages. Human resources are the main challenge to providing public services at the village level. In the context of health services, health human resource shortages, insufficient capacity training, and limited infrastructure produce low-quality services 31,51. Budget allocation from village funds and guidance from the community health centre to Posyandu lansia are alternative solutions to overcome problems related to the low quality of services.

Community Supports

Social capital is the key to the successful implementation of health services for community-dwelling elderly in rural areas. Local networks, volunteer altruism, and a sense of kinship among people are substantial factors that influence health program sustainability in communities 15,35. Community participation as a social concern for the elderly in rural areas has strengthened the implementation and sustainability of the program. This review has explored the existing forms of community support that underpin health services for the elderly in rural communities, such as volunteering to manage Posyandu lansia, self-funded training for upgrading skills, peer support for maintaining regeneration and participation, and funding. The supports have several benefits due to the nature of community involvement which relies on local resources to implement the program, fosters bottom-up initiatives to better identify problems faced by the elderly which encourages real action to overcome them, empowers the community to get involved, and encourages donations, grants, and volunteers’ contributions for sustaining the program. This finding is consistent with previously published works that found that public participation and engagement in community-based healthcare optimized health program intervention and yielded positive public health impacts 52,54. Moreover, social capital and community involvement are essential to enhancing community-based healthcare governance, in which organizational partnerships and trust become the foundation for its implementation and ensuring program sustainability.

In rural communities, the role of the family is also a determining factor for elderly healthcare. Elderly individuals rely on matrilineal kin to obtain care from health programs 34. Posyandu lansia services are sometimes difficult to access for the elderly, particularly those with poor health status. Thus, families should take them to Posyandu lansia. If elderly individuals require more intensive treatment, then the family will take them to the community health centre or hospital 55. For families who have elderly relatives in poor health, which influences their ability to perform daily living activities (e.g., dementia), the family burden to provide special personal care will be increased 36. Caring for the elderly with dementia requires careful and intensive treatment and monitoring, which also causes financial, social, physical, and psychological consequences 56,57. The physical and mental health of caregivers can be adversely affected; however, they often feel like they must take care of their parents or relatives in the hope that their health will improve 36. Insufficient healthcare infrastructures in rural areas for dealing with the elderly under specific circumstances leave families as the primary option 55,58,59.

Community and Family Awareness

Barriers to implementing health services for the elderly also come from within families and communities themselves. Challenges faced include a lack of family and community awareness of the health of the elderly such as the perception that the elderly are an economic burden to the family, unpleasant responses from the community members to cadre activities, and lack of financial rewards. This condition occurs because of the inadequate social protection policies for the elderly and insufficient managerial support from the community health centre to Posyandu lansia. The presence of elderly individuals in the family can be perceived as a financial and economic burden for the head of the household, as the elderly are no longer economically productive and require medical treatments 32,55. In developing countries, including Indonesia, where social protection (e.g., income benefits) for the elderly is limited and segmented, the burden of their presence will become an intergenerational family responsibility 34,60. Policies focussing on care provisions for the elderly under a social security system may be a substantial solution for dealing with the welfare of older people in Indonesia 61,63.

On the community level, the implementation of health services for community-dwelling elderly in rural areas sometimes receives a pessimistic response from community members, particularly to home care volunteers 32. Unpleasant feedback from community members toward the kindness and sincerity of health cadres causes psychosocial burdens for the cadres themselves; however, this does not discourage the enthusiasm of cadres to serve communities. Previously published works found that community health volunteers experienced burdens related to their social awareness activities, but these activities also had a positive impact on life satisfaction. Still, they negatively affected happiness 64,65. In many cases, unfamiliarity with health volunteers caused people to have a lack of interest in cooperating with community-based health programs 66. Therefore, managerial support from healthcare institutions and other stakeholders requires additional attention because community health volunteers have significantly contributed to primary healthcare services 65,67.

Further, health cadres encounter barriers concerning incentives 32. Payment models for health cadres have become a global discourse with a variety of approaches. Community-based health services for the elderly are not business-oriented without any commercial purpose. “Altruistic capital” may have an important role in health cadres’ motivation to serve communities 68,69. Although evidence shows that the remuneration of community health volunteers in several developing countries is potentially effective in improving work performance and motivation, the design depends on the context in which it operates, the availability of funding, and government commitment 70. Maximizing community appreciation and grassroots support through donations and grants for health program implementation may also be a realistic way to enhance motivation and program success because the issue of payment requires more complex bureaucracy and systems 32,70,71.

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, this synthesis focused on published evidence with rigorous search strategies using common database platforms for literature reviews to find papers that covered the implementation of community-based health services for the elderly in rural Indonesia. It is possible to leave out any relevant studies that could not be analysed from this synthesis. In addition, the review proposed to evaluate the interventions carried out in all regions of Indonesia; however, most studies were conducted in Java, where the vast majority of citizens live, while the other two studies were from Sumatera and Sulawesi. Moreover, because Indonesia has multiple ethnicities with a variety of cultures and traditions, as well as a disparity in healthcare provision among regions, this synthesis may not be able to identify this diversity. However, the study has contributed perspectives on the health service praxis for elderly people in the Indonesian healthcare context.

Secondly, the review covers not only papers with quotes from original studies but also those without any supported quotes. The decision to include all of these studies was made because of the assumption that publication requirements limit the number of words for manuscript submission. Thus, authors tend not to present quotes in their study results. However, it was emphasized that all included papers for this review were based on existing evidence that supports the main purpose of the study. This effort had been conducted by identifying the appropriateness and alignment of study objectives, methodological quality (e.g., the accuracy of informants, data collection, and data analysis), and qualitative findings from the included papers. To increase the degree of trustworthiness in selecting the papers and reducing the risk of errors and bias in the review process, a comprehensive check from different reviewers was conducted by using a standard critical review 23,24.

Thirdly, the studies included in the review were not merely focused on qualitative evaluations of interventions related to community-based programs for the elderly. The review also covered studies that explored participant perspectives, practices, and experiences toward healthcare from both sides of the elderly and stakeholder views. This approach enriched the angle of the situation of the healthcare system for rural elderly populations at the community level. Moreover, in terms of research design, different qualitative methods, such as phenomenology, ethnography, action research, and other study approaches that were included in the review may have provided a variety of perspectives and insights that require strict categorizing processes to generate robust synthesized findings or themes. This effort has the advantage of producing a more comprehensive interpretation of the findings.

In conclusion, the review has been able to highlight important findings about enablers and barriers to health services for community-dwelling elderly in rural Indonesia. Four main findings - the integration of healthcare, quality of service, community support, and community and family awareness - were identified to influence the implementation of healthcare for the elderly. These concepts provide substantial insights that can be used to address the key challenges of existing programs and improve the system by considering specific features of enablers and barriers. Evidence suggests that collaboration between communities, healthcare institutions, families, and government authorities can support program success and maintain service sustainability, which will result in adequate healthcare for elderly populations and improved health overall, as these services are intended to provide.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jenderal Soedirman University, Indonesia, for providing the research grant and IPSR Mahidol University, Thailand, for supporting the collaboration.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Funding Sources

This study was financed by Jenderal Soedirman University under International Research Collaboration grant.

Author Contributions

The conception or design of the work: B.A., S.M., and D.A. Data acquisition: B.A., A.D.I., and D.A.W. Analysis and interpretation of data: B.A. and D.A. Drafting the paper: B.A., S.M., and A.D.I. Critical revision of the intellectual content: D.A. and D.A.W. Study supervision: D.A.W.