Background

Food skills are an essential set of skills for life 1 and they are defined as a complex, interrelated, and person-centred set of skills that are necessary to provide and prepare safe, nutritious, and culturally acceptable meals for all members of one’s household 1),(2. Food skills are a component of food literacy, which is defined as the set of skills and knowledge that facilitates informed choices regarding eating habits, considering the impact that these choices have on health and economic, social, and environmental sustainability 1),(3)‒(5.

Among the diversity of skills included in food skills, we can identify the following: the ability to access and interpret the nutritional information on food labels; the ability to plan meals and manage the budget; the ability to conceptualize food, including adjusting recipes and using leftovers; ability to use mechanical techniques, including chopping, mixing, and following recipes; and ability to safely store and prepare food 1), (6), (7. According to the current literature, higher food skills (FSks) are associated with healthier eating habits 4, including a higher intake of vegetables and fruits and a lower intake of fats, sugars, and ultra-processed foods 2), (4), (8),(9),(10. Also, higher FSks seem to be associated with better health, mainly by preventing the development of excessive weight 11), (12.

Cooking skills are defined as the organization and transformation of ingredients to produce a meal, involving a variety of skills and competencies related to the technical act of preparing food and the ability to plan, cook, and deliver food within the food environment, time, and budget constraints. Cooking skills include some of the competencies from FSks that allow individuals to decide, prepare, and produce meals 13.

In general, university students have low FSks, which is one of the identified barriers to compliance with healthier eating habits 14), (15. University admission is characterized by an increase in unhealthy eating habits, like the low consumption of fruits, vegetables, pulses, whole grains, and fish, a high intake of snacks, red meat, and sugars, and the habit of skipping breakfast 16. By promoting the development of FSks among university students, we may counteract the presented tendency and promote healthier eating habits among this population 2), (17), (18.

Many intervention programs, targeting FSks, have been developed 4; however, methodological limitations have been identified, such as the use of non-validated assessment tools 4), (11), (19. Two of the main barriers to the development of measuring tools are the lack of standard references 4), (20 and the non-recognition of FSks as an autonomous set of skills, leading to the non-inclusion of important elements 21), (22. Some other limitations found in previous tools include the reference to specific foods, the targeting of specific intervention groups, and the absence of short definitions of the measured skills 21)‒(23. Besides the limitations identified during the development of the measuring tools, other issues have also been found in their validation, including the use of small, highly educated, and mainly female samples, the use of test-retest biased samples, and the existence of self-selection bias 22)‒(24.

According to our research, only one study assessed the cooking skills (CSks) of Portuguese students, using a 6-item questionnaire 25. No study has been found regarding the development and validation of an assessment tool for the evaluation of FCSks, or their promotion among young Portuguese adults.

In response to the need for the evaluation and promotion of food and cooking skills (FCSks) in young Portuguese adults, the present study intends to validate for this population, the FCSks questionnaire of Lavelle et al. 22, which considered all the barriers previously addressed. Also, we intend to characterize the FCSk as being of the same population.

Objective

The purpose of this research was to validate the questionnaire to assess the FCSk for the young Portuguese adult population through the assessment of psychometric properties. Several goals were pursued: (a) questionnaire validation and (b) characterize the FCSk in the evaluated sample and identify possible differences among different groups using sociodemographic variables.

Methodology

This research was a cross-sectional study among university students from Portuguese Higher Education Institutes.

Questionnaire Development

The development of the questionnaire started with a review of the scientific literature regarding the FCSk among young adults and its impact on food choices and health status. The availability of tools for assessing FCSk was also analysed. Researchers found a study from Brazil 26 and another from the USA 22 that developed and validated different questionnaires to evaluate individuals’ FCSk. After careful analysis of both tools, researchers decided to develop a Portuguese version of the questionnaire from Lavelle et al. 22 since it included more broad questions about FCSk and because it clearly separated food skills from cooking skills. To proceed with this adaptation, authorization was obtained from the authors.

The original questionnaire evaluates FCSk as separate dimensions: the CSks block, with 14 questions, and the FSks block, with 19 questions. Each question is rated on a scale from 1 to 7, where 1 means “not confident” and 7 means “highly confident.” An option for “never/rarely do it” is also included in the scale (scored as 0). The total confidence score results in the sum of the points given to each question. This process is applied separately for the CSks block and FSks block, resulting in two independent scores 22. The questionnaire was initially designed to evaluate these skills separately, but researchers may use these two scores to calculate a global score for FCSk.

Two researchers (C1 English level) translated the questionnaire. After completing the Portuguese translation, respective retro-translation was carried out by another two researchers (C1 English level) and reviewed by an English proficiency professional. This version was sent to be validated by the original authors. Along this process, researchers added two more questions in the CSks block, one for “cooking soup” and another for “cooking pulses,” two culinary practices that are very popular and traditional in Portugal 27. The third block regarding sociodemographic factors (e.g., gender, age, height, weight, degree, cooking frequency, and type of food pattern) was added for correlation purposes.

The final questionnaire was composed of 3 blocks: (1) CSks (16 questions); (2) FSks (19 questions); and (3) sociodemographic data (15 questions). Researchers used the same 1-7 scale as the original article, resulting in a total confidence score range of 16-112 points for the CSks and 19-133 for the FSks. Additionally, by calculating the theoretical quartiles of scores, a classification was established for the confidence level of CSks (≤32 low, 32-64 moderate, 64-96 high, and >96 very high) and FSks (≤38 low, 38-76 moderate, 76-114 high, and >114 very high). The Portuguese version of the questionnaire is presented as online supplementary Material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000530672).

Participants

University students from Portuguese Higher Institutes in Portugal, ages above 17 years old, could fulfil the questionnaire and be part of the sample. Researchers obtained a convenience sample through the dissemination of an online link to the questionnaire among all the university students from three different universities in the cities of Lisbon and Coimbra. No exclusion criteria were applied.

The questionnaire was filled out anonymously and autonomously by the students. Before filling out the questionnaire, participants signed written informed consent. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saúde de Lisboa (CE-ESTeSL No. 11-2022). Data collection occurred from January to May 2021.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the Statistical software R version 4.0.3. The results were considered significant at the 5% significance level.

Questionnaire Validation

Questionnaire validation included several steps: (1) internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire measures; (2) exploratory analysis to assess if described measures of CSks and FSks were related but distinct (two different factors); and (3) confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the model that resulted from the second step. For the first step (internal consistency and reliability), Cronbach’s alpha was used, considering a value above 0.75 as highly reliable and consistent 28. For step two, principal component analysis (PCA) was used to verify that items under each dimension of FCSks matched the ones from the original questionnaire. An oblimin rotation was performed. The overall Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were examined and returned a value of 0.89, which is good for the analysis 29.

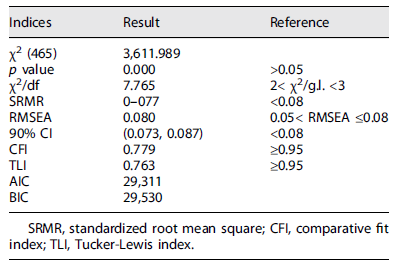

Finally, CFA was performed. A structural equation model, using the variables and loadings from PCA was analysed, considering an overall model fit using fit indexes (χ2 (p > 0.05), standardized root mean square (≤0.08), comparative fit index (≥0.95), and Tucker-Lewis index (≥0.95)) 30), (31. Raykov’s rho was used to evaluate the reliability of the CFA, considering a value above 0.7 as reliable 32.

Researchers perform all the statistical analyses for the original measures and the final version of the questionnaire 22. No differences were found in the psychometric properties, so only results relating to the final version of the questionnaire are presented.

Characterisation of FCKs

For the characterisation of the sample, frequency analysis was used (n, %), for qualitative data and for quantitative data, mean ± standard deviation was used. Due to the absence of a normal distribution of the data, as well as the presence of ordinal and scale variables, non-parametric analysis was deemed as the best choice, and Spearman’s correlation and the Mann-Whitney U test for comparisons among two different groups 28.

Results

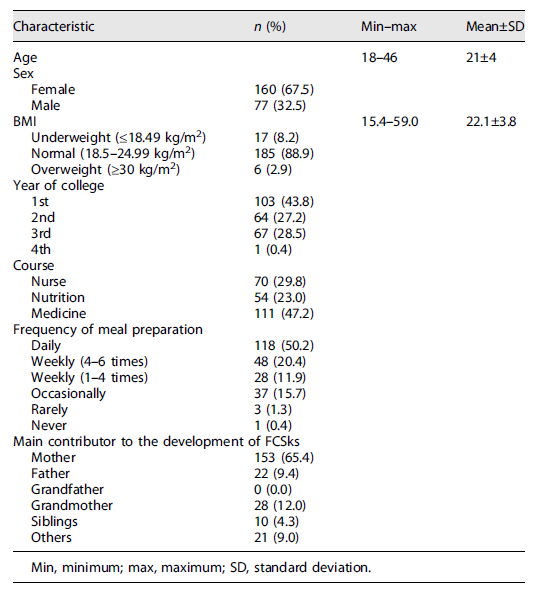

The questionnaire was answered by 275 university students from three Portuguese public institutions. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Most of the respondents were female (67.5%), and the average age was 21 ± 4.2 years old. Most of the sample (88.9%) presented a normal body mass index (BMI) and prepares meals daily. The mother is referred to as the major contributor to the development of FCSk.

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics of the studied sample (n = 275)

Min, minimum; max, maximum; SD, standard deviation.

Questionnaire Validation

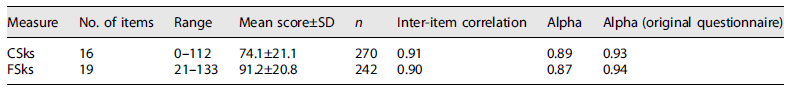

The internal consistency reliability was 0.89 for cooking skills and 0.87 for food skills (Table 2). The inter-item correlation mean was 0.91 for cooking skills and 0.90 for food skills. A moderate positive correlation 33 was found between FCSk confidence (r = 0.658, p < 0.01), indicating that the two measures are related.

Table 2 Internal consistency reliability of the CSks and FSks confidence measures: number of items, range, mean, and standard deviation (SD), inter-item correlation mean, Cronbach’s alpha

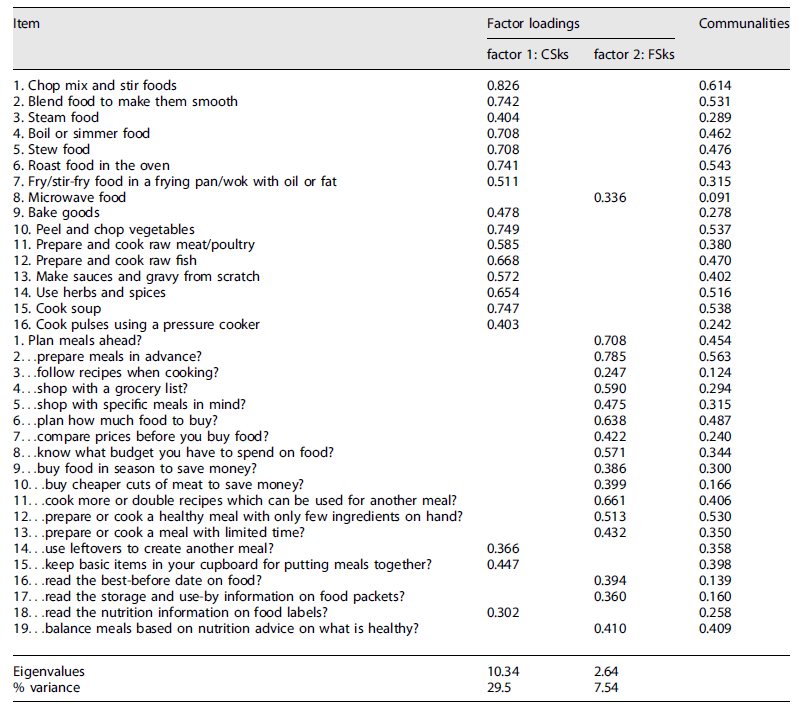

Regarding PCA, Bartlett’s test of sphericity and KMO returned an overall MSA = 0.89. PCA resulted in two factors, both with eigenvalues over 1 (Table 3). The first component accounts for 29.5% of the variability and the other for 7.5%. The loadings for each variable indicate that most of the CSks and FSks fall into their original component, with some exceptions. One CSks item (c8. Microwave food) had a higher loading for FSks (factor CSk = −0.176, factor FSk = 0.336), and three FSks (f14. Use leftovers to create another meal; f15. Keep basic items in your cupboard for putting meals together; and f18. Read the nutrition information on food labels) had higher loading for CSks (F14. factor CSk = 0.366, factor FSk = 0.339; F15. factor CSk = 0.447, factor FSk = 0.290; F18. factor CSk = 0.302, factor FSk = 0.296).

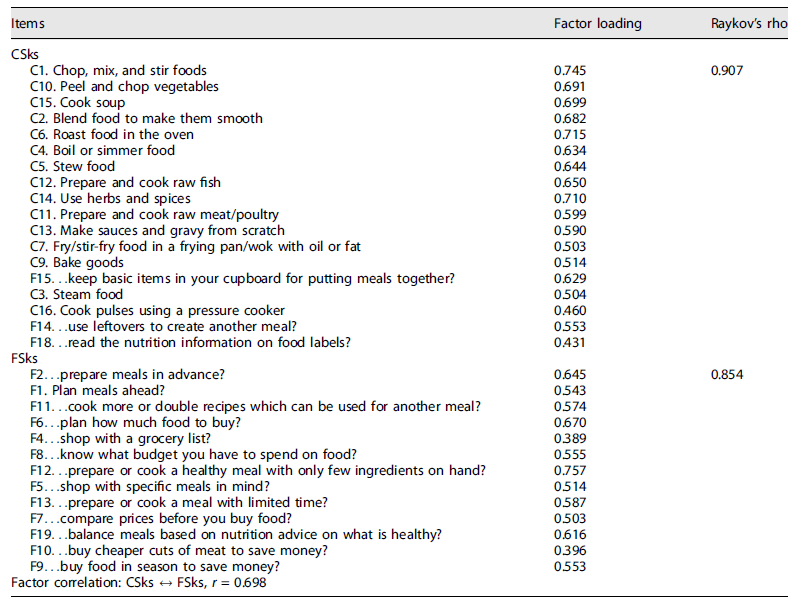

A model based on the PCA was used for the confirmatory analysis. Results are presented in Tables 4 and 5, showing a good adjustment model for most of the fit indices. The factor correlation between the two confidence measures is r = 0.689, p < 0.01.

Table 4 Fit indices of models

SRMR, standardized root mean square; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis index.

FCSks in University Students

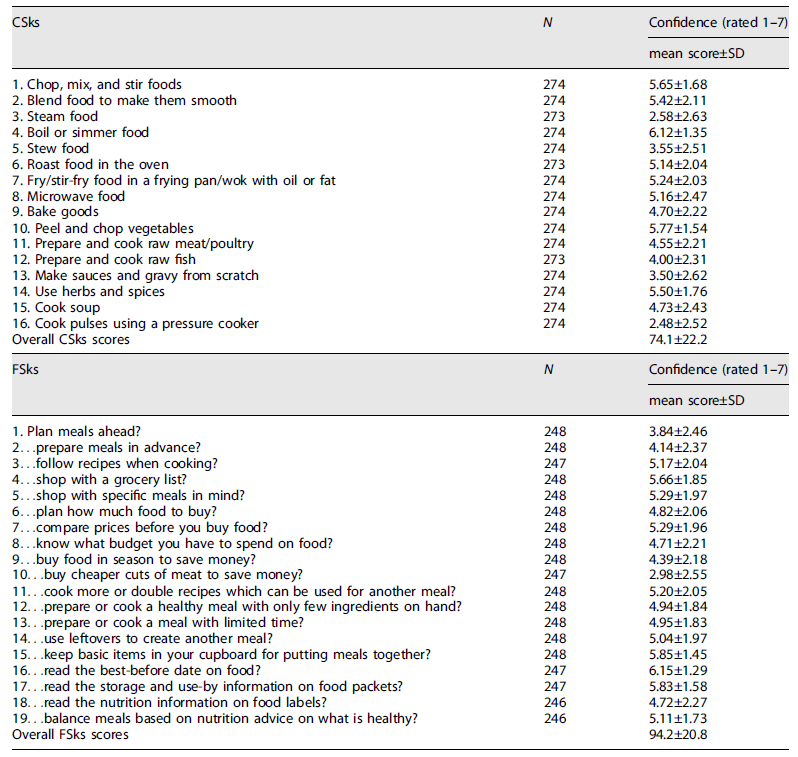

Table 6 presents the mean scores for FCSk confidence measures. The overall score is 74.1 (moderate) for CSks and 94.2 (high) for FSks. Cook pulses using pressure cooking (x¯FS = 2.48 ± 2.52), steaming food (x¯FS = 2.58 ± 2.63), and making sauces from scratch (x¯FS = 3.50 ± 2.62) are the CSks with the lowest score, while boil or simmer food (x¯FS = 6.12 ± 1.35), chop and peel vegetables (x¯FS = 5.77 ± 1.54), chop, mix and stir food (x¯FS = 5.65 ± 1.68) are the ones with the highest score.

For FSks, the ability to buy cheaper cuts of meat to save money (x¯FS = 2.98 ± 2.55) and plan meals ahead (x¯FS = 3.84 ± 2.46) score the lowest value, while reading the best-before date on food (x¯FS = 6.15 ± 1.26) and reading the storage and use by information on food packets (x¯FS = 5.83 ± 1.58) score the highest value. Upon analysing the FCSk level by variable, no difference was found among sex (pCSk = 0.576; pFSk = 0.158), age (pCSk = 0.566; pFSk = 0.130), class of BMI (pCSk = 0.903; pFSk = 0.320), or course (pCSk = 0.169; pFSk = 0.126). Significant differences were found for interest in gastronomy and frequency of meal preparation (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to validate a Portuguese version of the tool to assess FCSks, developed by Lavelle et al. 22. Internal consistency reliability returned a Cronbach’s alpha within the desirable values, although slightly lower than the ones obtained by the original authors 22.

As for the PCA performed, the significance of Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the excellent KMO index confirmed the executability of this procedure and the adequacy of the factor structure. Most of the items presented a factor loading that fell within the expected category. An exception was found for c8. Microwave food presented a higher loading for food skills instead for cooking skills. In the original validation, item c8. Microwave food also fell out of the CSks component into a third factor 22. This may be because microwaving may be considered not a real culinary competence, as mentioned by other authors 22.

Three items from FSks presented higher loadings in the Cooking Skills category and three items from the Food Skills - f14. Use leftovers to create another meal; f15. Keep basic items in your cupboard for putting meals together; and f18. Read the nutrition information on food labels. The first two also presented this behaviour in the original questionnaire validation. The authors argue that these skills have been identified as FSks in the previous literature, supporting the choice of leaving them in the Food Skills component 22.

The results from the CFA showed that the measures that indicated a good fit is within or close to the ranges, suggesting an acceptable fit of the model to the data with good psychometric properties. Therefore, researchers decided to keep the structure of the questionnaire, following the methodology used by the original authors 22.

The student sample showed a high level of Cooking Skills (x¯CSk = 74.1 SD ± 22.2). Different results were found among the student sample of the Lavelle et al. 22 study (x¯CS = 58.83, SD ± 16.45), which indicates that Portuguese students have better skills. The CSks with the highest score (c4. Boiling and simmering food; c10.Chopping and peeling vegetables, along with c1. Chopping, mixing, and stirring food) were the same as the ones identified in the Lavelle et al. 22 study. Nevertheless, contrary to our sample, Lavelle et al. 22 also scored high values for microwaving, frying/stir-frying, and using herbs and spices, which might indicate that our sample may have lower consumption of fried food and pre-prepared meals or that meals are not eaten at home. The Cooking Skills with the lowest scores were the following: c16. Cook pulses using a pressure cooker, c5. Steam food, and c13. Make sauces and gravy from scratch. These skills also had the highest variability, which may indicate that the ones who do not feel competent with these CSks do not feel competent at all, and the ones who do are completely comfortable. This also highlights the importance of developing CSks not only from an early age but also mostly during this period of life, in which many young people leave home and become more independent, developing lifelong skills.

Regarding Food Skills, our population showed a high level of skills (x¯FS = 94.2, SD ± 20.8). Like Cooking Skills, we also found higher results when compared to the Lavelle et al. study 22. The Food Skills with the highest scores were the following: c16. Read the best-before date on food and c17. Read the storage and use-by information on food packets. When compared to the results of Lavelle et al. 22, only reading the best-before date also had a high score, along with following a recipe, keeping basics in the cupboard and planning meals ahead 22. Interestingly, in our study, “planning meals ahead” had the second-lowest score, which may be consistent with the cultural difference between the two countries.

The FCSk with the highest and lowest scores reflect the eating habits of our sample. According to the literature, regarding the eating habits of children, adolescents, and Portuguese adults, there is a low consumption of pulses 34), (35, the food group which our sample found harder to cook. Due to their nutritional composition (fiber, complex B vitamins, iron, zinc, magnesium, phosphorus, and antioxidants), pulses consumption is associated with better health status 36), (37.

When comparing the ability to cook and prepare meat and fish, our sample had more difficulty cooking fish. This difference also seems to reflect the eating habits of Portuguese young adults, where meat consumption is higher than fish consumption 34. This fact may reflect in health status since fish consumption is associated with health benefits, like the prevention of cardiovascular diseases 38, while high meat consumption is associated with the development of chronic diseases, namely, cancer 39), (40, which states the importance of FCSks interventions to promote good eating habits and health. Moreover, reducing meat consumption is widely recognized as an important factor towards sustainability, which along with increased consumption of pulses and nuts is quite relevant towards plant-based food patterns. Investing in the ability to cook pulses could help this necessary change and approach young people to the Mediterranean diet.

Similarly, to Lavelle et al. 22, the FCSk with the highest score reflected a preference for quick and easy meals, characteristic of the university student’s diet. Developing the FCSk that will allow young people to create healthy and sustainable meals that are tasty and quick to prepare may lead to better food habits and better health.

Our data showed that individuals with a liking for cooking and having a higher frequency of meal preparation had higher levels of FCSk. Similar outcomes have been found in other studies 2), (41), (42. These results come as no surprise since the more we practice a certain skill the more we develop and enjoy the skill. In addition, the more we like to do a certain activity, the more we practice it. Future FCSk interventions should focus on creating positive experiences and integrating these skills into the daily routine.

Unlike some studies 2), (41, where a higher FCSk level was found among women, our study showed no differences among different sex. Traditionally, women have been responsible for attending to household tasks, including preparing and cooking meals 43. However, in recent years, while women have been dedicating less time to house chores and meal preparation, men have been spending more time on these activities 2), (43. Our data reflect this evolution of “gender roles.”

No differences were found between age and the student’s degree, which also contradicts the findings of most studies, where older individuals and individuals with a nutrition degree tend to have higher FCSk levels 41. These results may be so because our sample is very close in age and most students are taking a nutrition or health-related course.

Finally, no differences were found in the BMI classification among the FCSk level. A recent study also found similar results 44. Weight gain is influenced by multiple factors, being one of them the level of FCSk 45. Nevertheless, there is a diversity of factors involved in weight gain, which may explain why no difference was found among the BMI classification.

Limitations and Strengths

The present study had some limitations, namely: (1) the use of a self-field questionnaire which may lead to the overestimation of the participants’ FCSk level; (2) the self-assessment of height and weight, leading to a possible underestimation of BMI; (3) the evaluation of the FCSk on university students from health degrees, which could explain the high level of FCSks found. Also, researchers are aware that this is not representative of Portuguese university students since it included only health degrees and two Portugal regions. However, some strengths can also be identified as follows: (1) the proximity between the results of these studies and the Lavelle et al. 22 study, showing positive reliability on the developed questionnaire; (2) the characterisation of the level of FCSk among Portuguese adults, being one of few studies presenting these analyses.

Conclusions

This research successfully validated a Portuguese version of the questionnaire to measure the FCSks of the young adult population. Although the validation was performed among a group of young adults, researchers consider that it can be applicable to older adults and teenagers over 15 years old, in future research relating FCSk and eating habits. The questionnaire identified lower competencies on FCSk associated with healthy foods and cooking procedures, such as cooking pulses and vegetables. This may compromise the adoption of healthy eating behaviours, so promoting FCSk in young adults may pose a strategy for nutrition and public health in reducing diet-related diseases. More studies are needed, involving a larger and more diverse sample, for a better characterization of FCSk and studying their relation to eating patterns.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Fiona Lavelle and all authors from the original questionnaire for authorizing the Portuguese translation. Authors thank Joana Sousa from Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa for the support in this research. Authors would also like to thank Maria José Pires from Escola Superior de Hotelaria e Turismo do Estoril for the English and grammar review.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saúde de Lisboa, with the approval number CE-ESTeSL-No. 11-2022. Informed consent was obtained from participants to participate in the study.

Author Contributions

Vânia Costa, Rute Borrego, Cátia Mateus, and Cláudia Viegas prepared the questionnaire. Cátia Mateus, Elisabete Carolino, and Cláudia Viegas analyse the data. Cátia Mateus and Cláudia Viegas wrote the first draft with contributions from Elisabete Carolino. All authors reviewed and contributed to the subsequent drafts of the manuscript.