Introduction

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “an unpleasant experience that may or may not be linked to actual tissue damage”. In the case of chronic pain, the currently most accepted definition refers to pain that lasts longer than the expected time for tissue healing, that is, more than 3 months. The most common causes for the onset of chronic pain in the musculoskeletal system, which generates severe disabilities, are osteoarthritis (OA) and back and neck pain. Best clinical practices recommend self-management strategies for this type of patient, including pain education and exercises with the patient’s active participation in a lifestyle change, always encouraging shared decision-making between physicians and therapists 1.

Notably, conservative care administered in a clinical setting is expensive, and ongoing monitoring is often unfeasible. In this sense, telehealth is a promising option to deliver self-management strategies, using related technologies and services to enable synchronous or asynchronous interactions between healthcare professionals and patients. Telehealth interventions add important value to chronic pain management and treatment programs as they overcome geographic barriers between patients and physicians 2.

One of the most affected segments with the highest prevalence of chronic musculoskeletal pain is the knee joint. OA is one of the main causes of chronic knee pain, considered a public health problem in people over 45 years old, affecting approximately 10% of men and 18% of women over 60 years old due to muscle weakness 3. Without immediate action, the increasing prevalence of OA becomes an unsolved challenge for health systems and society worldwide 3-5.

However, conventional delivery of rehabilitation with exercises requires patients to participate actively and face-to-face in clinics, which involves a commitment of time, motivation, and financial cost. Another option is the practice of supervised exercises, which requires patients to perform exercises with access to limited resources, which can lead to low adherence and/or clinical evolution 5.

In face of these difficulties, in recent years, telehealth has gained prominence in the field of health rehabilitation. The term “telerehabilitation” has been widely used and is defined as “the provision of rehabilitation services through communication and information technologies.” For the World Health Organization (WHO), telehealth means the provision of healthcare-related services in cases where distance is a critical factor, expanding assistance and coverage 6.

This initiative allows the development of actions to support care, health, and continuing education in health areas. In the case of speech therapy, for example, the practice of telehealth is considered the exercise of the profession through the use of communication and information technologies, with which health services such as teleconsultation, second opinion, telecounseling, telediagnosis, telemonitoring, and tele-education can be provided 7.

Telerehabilitation follow-up may overcome one of the barriers to face-to-face treatment in clinics and offices, which includes financial and transportation difficulties, as well as access to professionals, which ends up generating low adherence to treatment 8. Telerehabilitation has become a relevant modality, in which the barriers to accessing information technology and remote connection have been overcome with the diversification of ways of delivering content to patients, with the use of smartphones for videoconferencing being one of the preferred ways to provide services to people outside the rehabilitation clinics 8-10.

The decision between the two rehabilitation options can be based on patient and healthcare professional preference, which is associated with high patient satisfaction due to reduced transportation and treatment expenses, in addition to time saving. This approach may empower patients to take a proactive role during treatment and to self-manage chronic pain symptoms 4,11,12.

The literature investigating the use of telerehabilitation for the control of chronic musculoskeletal conditions continues to grow. A clinical trial evaluated the effectiveness of telerehabilitation services compared to daily face-to-face physical therapy sessions and demonstrated there is no difference in effectiveness, at least in terms of short-term results 13. Clinically, telerehabilitation within physical therapy encompasses a range of rehabilitation services, including assessment, monitoring, prevention, intervention, supervision, education, consultation, and counseling. In addition, professionals can still monitor exercise parameters and provide necessary changes or progressions of therapy 14.

The Internet as an efficient means is an option to deliver health content remotely administered by the physical therapist, as it allows educational material to be accessed online by people with chronic pain, such as knee OA. This combination of treatments is in line with the biopsychosocial approach to managing chronic diseases, and technology support increases the accessibility and attractiveness of exercise programs to treat knee OA 15.

This systematic review was justified by the little scientific production on this subject to date. Thus, the purpose was to verify the barriers to the implementation of telerehabilitation in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal diseases compared to face-to-face rehabilitation.

Methods

This review has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under No. CRD42022316488. The PRISMA guidelines 16 were applied to the PICO question (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Result), and the purpose was to verify the barriers to the implementation of telerehabilitation in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal diseases compared to face-to-face rehabilitation, as follows: the population was composed of older people with knee OA; the intervention was telerehabilitation; the comparison was face-to-face rehabilitation; and the primary outcome was physical function assessed with the WOMAC score (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index).

The electronic databases searched on March 1, 2022, were Pubmed, Scopus, Virtual Health Library (VHL), Cochrane, and Web of Science. The search was expanded by reviewing the references to the studies included to identify other relevant publications. The strategy was not limited to publication time, and there was no language restriction.

The search strategies followed the descriptors in health sciences (DeCS/MeSH), with the following terms in English: (“Osteoarthritis” OR “Knee joint” OR “Patellofemoral Syndrome” OR “Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome” OR “Anterior Knee Pain”) AND (“Physiotherapy” OR “Physical Therapy Specialty” OR “Physiotherapy Specialty” OR “Specialty Physical Therapy” OR “Specialty Physiotherapy” OR “Physical Therapy” OR “Physical activity”) AND (“Telemedicine” OR “Telehealth” OR “Telerehabilitation” OR “Tele rehabilitation” OR “Tele-rehabilitation” OR “Virtual Rehabilitation” OR “Virtual Rehabilitations” OR “e-Health”).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

As inclusion criteria, randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were selected that underwent treatment of knee OA, patellofemoral pain, telemedicine, telerehabilitation, telehealth, and e-health using intervention protocols based on physical exercises for the treatment of OA with a control group, telemedicine, and face-to-face care, following the principles of clinical assessment and reassessment through questionnaires and/or clinical tests. Articles from systematic reviews, published RCT protocols, pre- or post-operative knee or hip protocols, telemedicine interventions in areas other than physical rehabilitation and physical therapy, studies with athletes and young populations, or drug interventions were excluded.

Data Extraction

Two blinded authors (J.B.F. and A.A.V.) used a standardized form to independently extract data on study characteristics, such as details of the telerehabilitation exercise programs compared to face-to-face rehabilitation and statistical data. The results obtained included physical function, barriers, and facilitators of the intervention protocols for telerehabilitation and face-to-face rehabilitation, where an attempt was made to identify the data collection tools used in the control and intervention groups.

The articles were exported to an electronic data sheet and grouped by search platform with the following data: title, authors, year of publication, journal, abstract, and keywords. Individually, the two authors analyzed the eligibility of each article according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria already described. After the analysis, discrepancies were verified, and, by consensus, the authors excluded the studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria. These selected articles were again analyzed through the reading of the full scientific text and classified according to the objectives of this systematic review, following the research question. In case of discrepancy between reviewers (J.B.F. and A.A.V.), a third blinded author (W.Q.B.) would intervene.

Analysis of the Risk of Bias

For the analysis of the risk of bias in the articles selected, the Review Manager program (RevMan) was used and, as a source of information, the Cochrane Manual for the Development of Systematic Intervention Reviews, version 5.1.0 (Cochrane Handbook), which is a two-part tool containing seven domains, namely: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and professionals, blinding of outcome evaluators, incomplete outcomes, reports of selective outcomes, and other sources of bias. The first part is the description of what was reported in the study being evaluated, with sufficient details for a judgment to be made based on this information. The second part is the judgment of the risk of bias for each domain analyzed, which can be classified into three categories: low risk of bias, high risk of bias, and uncertain risk of bias. The random sequence generation, allocation concealment, and report of selective outcome domains should be considered in one single judgment for each study. As for the blinding of participants and professionals, blinding of outcome evaluators, and incomplete outcomes domains, two or more judgments can be used, as judgments usually need to be made separately for different outcomes or the same outcome at different times 17.

Analysis of the Quality of Evidence

The quality of evidence for the primary outcome of each study was evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach. For each outcome, the quality of evidence was downgraded by 1 high-quality level for each serious issue found in the risk of bias, inconsistency, indirection, imprecision, and publication bias domains 18.

Results

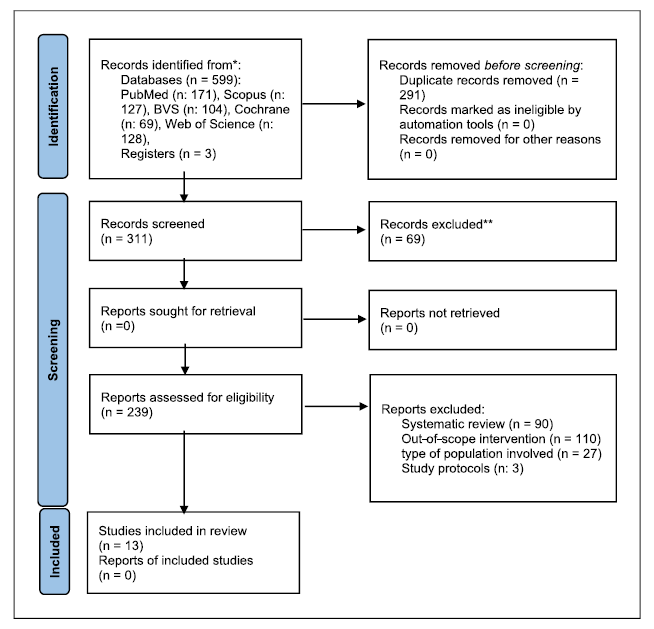

After applying all criteria, thirteen articles (n: 2616) were selected for this systematic review (shown in Fig. 1). According to PRISMA guidelines, 599 articles were found: PubMed (n: 171), Scopus (n:127), VHL (n: 104), Cochrane (n: 69), Web of Science (n: 128); and three other articles referenced in the studies and identified in the search were included in this review. The filter to remove duplicate articles was applied, which reduced the total to 311 articles.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the study selection process. This chart provides information on the number of studies identified, included, and excluded throughout the phases of the systematic review following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines 16.

Subsequently, 69 articles were excluded from the review conducted by humans due to inconsistencies such as, for example, title or abstract outside the scope of this review. A total of 227 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, as well as three other articles that were study protocols for a randomized controlled trial and that, therefore, did not present results and data.

Risk of Bias

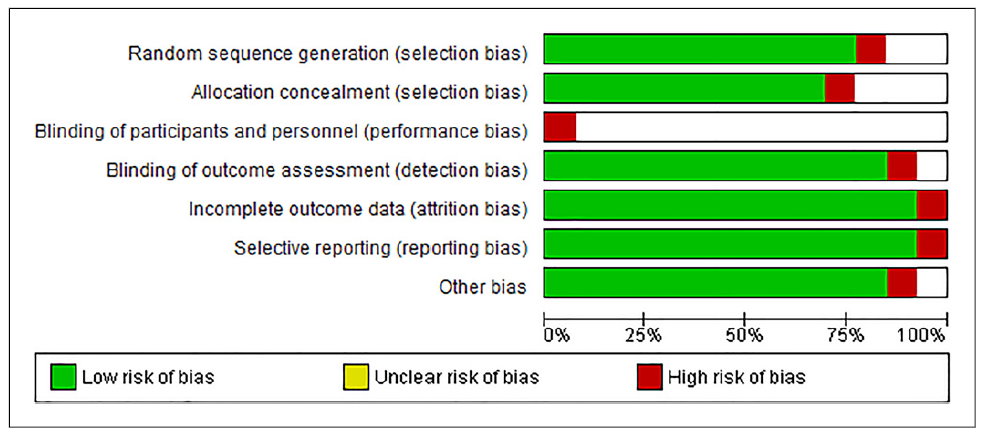

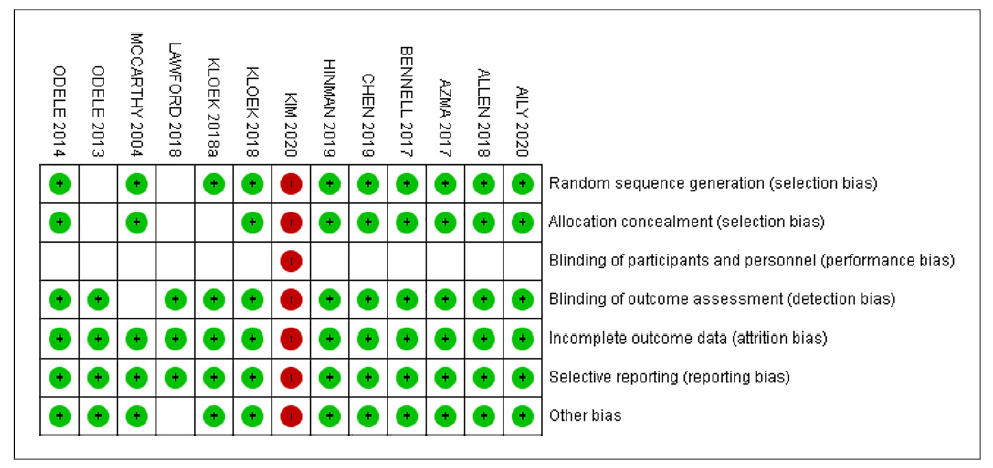

The results of the risk of bias assessment are shown in Figures 2 and 3. For the analysis of the risk of bias, the Review Manager program (RevMan) was used and, as a source of information, the Cochrane Manual for the Development of Systematic Intervention Reviews, version 5.1.0 (Cochrane Handbook) 19.

Fig. 2 Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments on each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Fig. 3 Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

According to the judgment of the authors of this review, only one (7.7%) of the studies 20 had a high risk of bias for all items evaluated due to a lack of control data. Details of random sequence generation were not reported in two (15.24%) studies 21,22. It was unclear whether allocation concealment was adequate in three studies (23.1%) 21-23.

No or partial blinding of participants and healthcare professionals was identified in 13 (100%) studies, and it was unclear whether outcome evaluators were blinded in three (23.1%) studies 21,24. Reports and other sources of bias were not identified in any of the 13 studies selected for this review.

Characterization

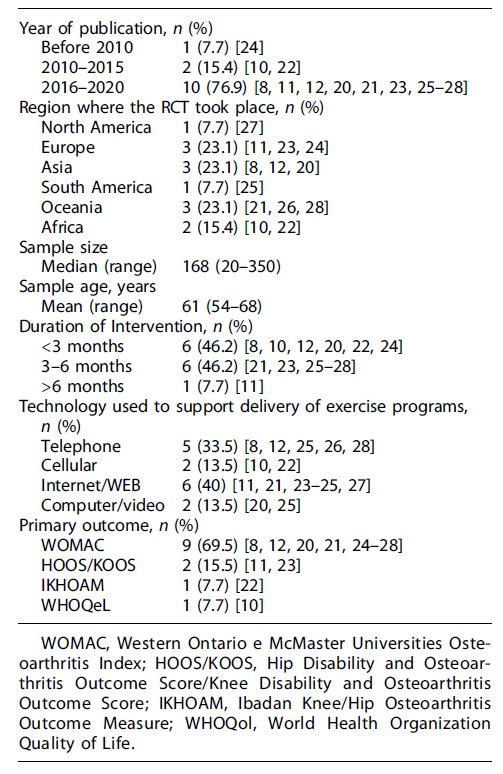

The characteristics of the 13 studies are summarized in Table 1. All RCTs implemented technology-supported exercise programs compared to face-to-face care for patients with knee OA for a variable period (6 weeks-12 months). During the protocol period, participants in the intervention group were encouraged to exercise, on average, three times a week. In the control groups, participants received face-to-face physical therapy associated with educational materials for OA management.

Physical Function

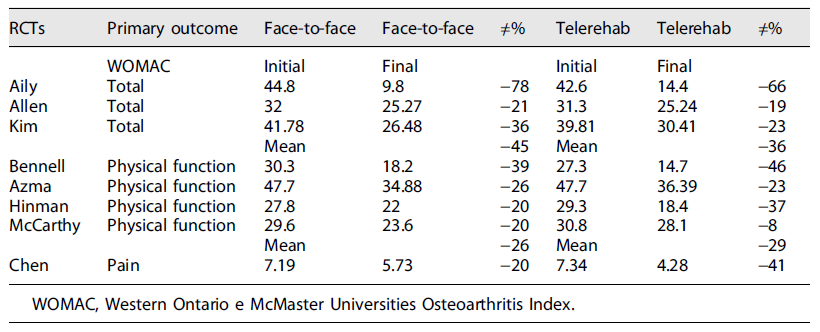

Improving functional conditions is the goal of rehabilitation for patients with knee OA. In nine of the thirteen RCTs 8,12,20,21,24-28, the most used score to assess physical function comparatively between groups was the WOMAC score (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index). This questionnaire consists of 24 items, divided into three subscales: pain (5 items), joint stiffness (2 items), and physical function (17 items). The total score ranges from 0 to 96 following a Likert scale, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for WOMAC should be 16 points 19. Two other studies 11,23 used the KOOS (Knee Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score), which is a self-administered questionnaire to assess the patient’s functional status in relation to knee issues on a 5-point Likert scale. One study 22 used the IKHOAM (Ibadan Knee/Hip Osteoarthritis Outcome Measure), which is an instrument to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in individuals with knee OA, for the assessment of the primary outcome. One study 10 used the WHOQoL (World Health Organization Quality of Life), which has four domains: physical, psychological, social, and environmental, with positive scores; that is, higher scores indicate better quality of life.

The results obtained in eight (62.5%) of the 13 RCTs included in this systematic review, regarding the primary outcome, when using the total WOMAC or its fractions, demonstrate that in all of them, there was a MCID (Table 2). None of the thirteen studies indicated harm to patients when undergoing physical therapy and/or health education through follow-up means such as the Internet, telephone, electronic messages, leaflets, videos, or applications, which characterize telerehabilitation care.

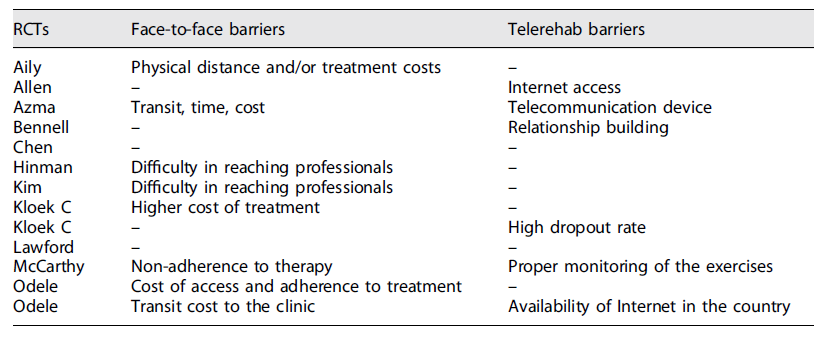

The analysis of this systematic review focused on the barriers found in the rehabilitation process, both via telerehabilitation and face-to-face, as shown in Table 3. In the telerehabilitation modality, the most mentioned barriers were Internet access and availability, adequate telecommunication devices, adequate monitoring of the rehabilitation program, difficulty in building the therapist/patient relationship, and high rates of program dropout. In the face-to-face modality, barriers to the implementation of therapy were also found, with emphasis on physical distance and treatment costs, travel time and travel cost, difficulty in accessing specialized professionals, especially in geographically more distant areas, non-adherence to therapy, or drop out due to difficult access.

Discussion

Getting patient involvement in telehealth interventions becomes essential to achieve positive results, but it can be extremely challenging due to various cultural, social, and economic barriers 29. This systematic review analyzed 13 RCTs regarding the effects on the physical function of patients with knee OA, in the short and medium term, less than 3 months (46.2%), and from 3 to 6 months of intervention (46.2%), through technology-supported exercise programs compared to face-to-face care.

According to the description of the results of this review, these programs were shown to be related to significant and clinically important improvements in physical function. The benefits of therapeutic exercise for people with knee OA are well established, with similar efficacy to analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but with fewer side effects and fewer risks than joint replacement surgery 30. Less sedentary people with knee OA have better physical function, regardless of time spent in moderate or vigorous physical activity 5,19,27.

The positive effects observed in telerehabilitation may be due to technological tools that provide more access to health resources make participants aware of the importance of health and exercise management, promote daily physical activity and exercise adherence, and may lead to better health-related results 27,31. The diversification of technology means for delivering exercises was a characteristic found in this review, which certainly facilitates the access and use of this resource, with the Internet/WEB being the most used means, corresponding to 40%. Approximately 250 million individuals suffer from OA worldwide, and the knee is the most affected joint, with an incidence of 16-17% in a population aged between 50 and 75 years 32. These data justifies the search for the telerehabilitation intervention model proposed by the studies included in this review to facilitate the access of this population to treatment aimed at controlling the predisposing factors to the pathology 30,33. The mean age of the population affected by knee OA found in this review was 61 years old, which is in line with the literature 34.

The comparison between exercise protocols supported by technology and face-to-face physical therapy demonstrated that both bring benefits to patients with OA, which was confirmed by the results of the average WOMAC score used in the assessment of the primary outcome in 69.5% of the studies included in this review. We know that the MCID considered is 16% and was reached by eight studies, two of which 19,28 obtained the best percentage results for both groups. These two studies have in common the protocol time until the primary outcome, which was 3-6 months, and the technology used to deliver the protocol, which was the telephone together with the Internet/WEB, due to the ease of access and use by users.

The means for the delivery of rehabilitation observed in the 13 clinical studies included in this systematic review indicate that there are barriers that may affect the result of the patient’s rehabilitation. For face-to-face rehabilitation, the main barriers mentioned were travel costs and travel distance, access to specialized professionals and clinics, and the difficulty in adhering to therapy. These barriers could be more easily overcome with greater coverage of health services, especially in more remote locations. The barriers to telerehabilitation are usually related to accessing the Internet and telecommunication devices, building personal relationships, and properly monitoring the exercise protocol. According to the literature, the diversification of the means of communication for the delivery of the rehabilitation protocol and the various possible ways of monitoring these patients at a distance, such as, for example, therapy sessions carried out synchronously and the scheduling of face-to-face assessments and reassessments to help build the therapist/patient relationship, are mechanisms that facilitate and remove barriers to this therapeutic modality.

The results presented in this review indicate that the barriers to the implementation of treatment protocols were overcome, leading to clinical results that demonstrated that there were no differences between the telerehabilitation and face-to-face rehabilitation groups for the clinical condition investigated in this review.

Limitations

Any systematic review of the literature is inherently limited by the number and quality of studies included in the review, and this research is no exception. In general, the literature on the use of telerehabilitation and the reach of this modality requires greater methodological rigor and conceptual focus. Additional research is needed to maintain greater standardization of the data collected and instruments used, with stratification of randomization for more homogeneous groups, more robust samples, and standardized exercise protocol, allowing a better understanding of the data collected with less interference or risk of bias, which also made the meta-analysis of this study unfeasible.

In this review, for example, few clinical studies considered randomization by OA severity, which certainly affects the understanding of the data collected, as well as the lack of gender segregation, as men and women have different coping strategies for this issue. The means of delivering technology seem to have been overcome, as several means were used in the studies included in this review and none reported difficulties regarding this aspect, the inclusion criterion being that the participant had access to the type of technology chosen for that research. Despite the limitations, this review provided a comprehensive summary of the trend and current state of telerehabilitation applications for this specific pathology, of high incidence in orthopedics, validating the review and bringing more light to the subject.

Conclusion

Telerehabilitation can be implemented and proves to be a promising strategy for patients with knee OA to have access to therapeutic exercise protocols, health education, and monitoring of the rehabilitation program at home, improving physical function, not being harmful, but compatible with face-to-face rehabilitation. This review demonstrated, mainly through the WOMAC score, positive results for telerehabilitation methods and face-to-face physical therapy. The barriers to telerehabilitation, which were more related to accessing the Internet and telecommunication devices, building personal relationships, and properly monitoring the exercise protocol, were overcome through the diversification of the means of communication for the delivery of the rehabilitation protocol; the various possible ways of monitoring these patients at a distance, such as, for example, therapy sessions carried out synchronously and the scheduling of face-to-face assessments and reassessments to help build the therapist/patient relationship, are mechanisms that facilitate and remove barriers to this therapeutic modality. More high-quality studies with large samples are needed, focusing on group stratification, uniform primary outcomes, and the long-term results of Internet-based rehabilitation for patients with knee OA.

Author Contributions

J.B.F. prepared the systematic review project, carried out the bibliographic survey and selection of articles, and wrote the review article. L.P.M. acted as a reviewer of the article and assisted in the writing and improvements of the methodology. L.L.B.S. acted as a reviewer of the article, elaborating and describing points for improvement and corrections. B.C.A. worked on drafting and researching the methodology and took part in selecting the articles used in the paper and writing the requested corrections. W.Q.B. acted in the orientation of the article, actively participated in the bibliographical review and selection of articles, and acted in the writing and corrections of the article.