Introduction

Men’s vulnerability in the sexual health context involves the social conditions that structure individual behaviors, effective public policies, and access to and use of health services. According to the International Planned Parenthood Federation and the UN Population Fund 1, sexual and reproductive health needs of boys and men are not met in health care. Epidemiological data have consistently shown that men have experienced marked disadvantages concerning health care, which has been illustrated by rates of sexually transmitted infections and morbidity 2 and mortality associated with prostate cancer. Difficulties in accessing care have consequences for men’s vulnerability to sexual diseases and impact their sexual partners, families, and communities 3.

Social representations about what sexual health is are produced, transformed, and reconfigured routinely by the actions of individuals and their experiences in their relationships with others, as well as over time by social relations and interactions in several contexts mediated by social norms and roles. They are understood as practical social theories, which organize the symbolic relationships between social actors 4 since they are the basis of communication logic 4-6 and shape these actors’ beliefs and stereotypes regarding what is meant by sexual health and being a man 7.

Social representations about sexual health are socially formulated and shared modalities of knowledge and contribute to the construction of a reality that is common to a social set. Production of meaning about what is understood as sexual health shapes action modes and practices, not only of ordinary citizens but also of health professionals when these develop their professional activities. Men’s access to sexual health care is influenced by the symbolic universe of nurses, translated into maps of signification and normative idealization that structure their practices.

For analyzing nurses’ social representations regarding men’s sexual health, taking into account the barriers to and possibilities of access to health care, language (centrality) was considered a builder of social reality itself in the following levels: micro (centered on experiences shared by nurses), meso (practice contexts and available means and resources), and macrosocial (training, institutional, and policy spheres).

Material and Methods

Study Type

Descriptive study with a qualitative approach was used. The technique used to collect data was a focus group, which consisted of discussion group prepared with the objective of gathering data about nurses’ social representations regarding men’s sexual health by considering the barriers to and possibilities of access to sexual health care. Interaction between the participants was promoted, and they were encouraged by the nondirective figure of the moderator to share their experiences and opinions 8. Carefully planning the focus group implied planning and executing all its steps, before, during, and after the meeting 8, which included general planning, recruiting, moderating, and data analysis.

Participants Selection

Nurses who developed their activities in primary health care and distinct types of differentiated care services were invited to participate, to obtain a heterogeneous group. Gender, context, and length of professional practice were also considered when trying to guarantee diversity. The inclusion criteria were nurses who worked in health services, had experience delivering care to men, and whose length of professional practice was longer than 5 years in health institutions in the Lisbon metropolitan area. The potential participants were contacted by e-mail or phone.

Ethical Guidelines

Data collection was carried out in 2021, after approval by the Ethics Committee at the Nursing School of Lisbon. Before the focus group, the participants signed written informed consent forms, and data confidentiality and pseudonymization were ensured. At the beginning of the recording of the focus group, information about the study context, objective, and method was reiterated, and permission for recording sound and images and publishing excerpts and results was requested again. The possibility of interrupting participation in the study was reaffirmed.

Data Collection and Study Variables

Data were obtained through an online focus group, and the Zoom platform was used to video record. Nine nurses participated in the 1-h and 53-m focus group, conducted by the main researcher and one of the members of the project. Data were obtained by analyzing the professionals’ interaction and their engagement in the discussion 8,9. The key questions were as follows: What possibilities/difficulties are there in the access of men to sexual health care and what do they seek? What are the paths of the search for sexual health care by men? To what professional groups do they resort? What expectations do they have? Do the obtained answers meet the care needs of men? Do men see nurses as resources? How do nurses characterize the interaction between nurses and men in the access to sexual health care? What are the possibilities/difficulties in the interaction and nursing care delivery to men in the sexual health area?

Data Analysis and Treatment

The interview was transcribed, and a text corpus was prepared for lexicographic analysis. Descending hierarchical classification (DHC) and similarity analysis were applied by using Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRaMuTeQ) software 10,11. Analysis results were interpreted and discussed by the researchers who participated in the focus group and two experts in the methodology used 11. The participation of the latter contributed to elucidating the relationship between the classes and inferring and interpreting the results.

The guidance provided by the checklist of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research was followed to report important aspects of research teams, study methods, study contexts, conclusions, analyses, and interpretations 12. IRaMuTeQ allows users to run statistical analyses of a text corpus. The authors opted to apply DHC and similarity analysis to treat the data. In its lexical analysis of the text corpus, the software cut 40-character excerpts, which were the analyzed text segments 10.

Results

Five nurses were women (55.6%) and four were men (44.6%). Two of them worked in primary health care, and the others worked in differentiated care: four were in the fields of emergency, external appointments, and hospitalization, and three in day hospitals and in the areas of hospitalization and intensive care.

The average age of the participants was 41.8 years, with a minimum of 27 years, a maximum of 56 years, and a standard deviation of 10.4 years. Two participants (22.2%) had been working for less than 10 years, three (33.3%) had between 10 and 20 years of experience, and four (44.5%) had been nurses for over 21 years. All the nurses had professional experience in differentiated care, and three were also experienced in primary health care.

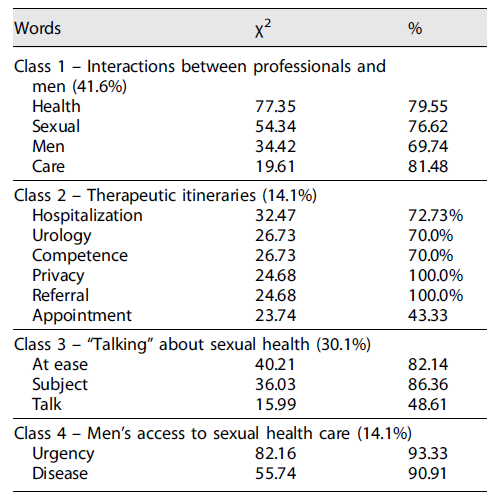

Text analysis resulting from the focus group indicated 11,254-word occurrences distributed over 1,054 forms, with an average of 11 words per form. The criterion used to define the threshold for inclusion of the elements in the classes of the dendrogram showed twice the average frequency (11 × 2 = 22) in the corpus and an association with the class with χ2 ≥ 3.84, with a level of significance of 95%. The selected words should predominantly have an χ2 higher than the reference value and p < 0.0001. However, it was not possible to observe the threshold criterion of twice the average frequency in classes 2 and 4, in which word significance was also used as a criterion.

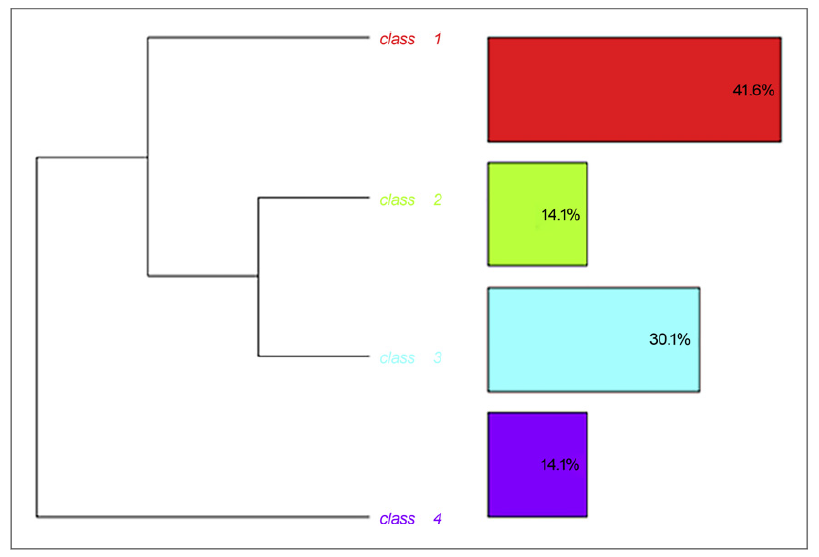

By applying DHC, 269 text segments were analyzed (out of a total of 317), which accounted for 84.86% of the corpus, from which four classes related to nurses’ social representations about men’s sexual health emerged, as shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The DHC dendrogram (Fig. 1) allowed the understanding of the expressions and words used by the nurses through an analysis of the paths of these elements and the places they occupied in the contexts of care delivery where the interactions with men occurred. Figure 1 shows the interclass relationships and must be read from top to bottom. This schematic representation indicated that classes 1 and 3 had a lower level of relationship or proximity with class 2.

Class 1 was entitled “Interactions between professionals and men,” and the vocabulary that stood out in it accounted for 41.6% of the text segments analyzed in the corpus. The words health, sexual, men, and care, whose χ2 are shown in Table 1, characterized with more significance the processes and contexts in which the interactions between professionals and men occurred. The existence of alterations in men’s sexual health triggered the search for health care, and primary health care was the setting in which men’s protagonism as care recipients was more evident.

(…) basically in family planning appointments, women’s health after menopause, and pregnant women. Men are always forgotten, for sure (P8).

When men’s sexual health is approached, it already has a lot to do with a problem. It may not necessarily be a disease, but it is faced as a problem and makes men talk about it (P9).

Although some words did not show reference values for statistical purposes, analysis of their semantics indicated that they reinforced statistically significant words. This occurred for the words primary and answer, which were identified in 100% of the text segments in class 1, and for problem, only, and women.

Men do not talk about their sexual health; either they are questioned directly about it, or do not talk much about it, or do if they have a problem (P5).

I believe that men’s sexual health is important, but I stress that they seek some type of help only when the problem has already begun, they do not care much about prevention or future complications that may exist (P2).

Class 2, “Therapeutic itineraries,” encompassed 14.1% of the analyzed text data. The words hospitalization, urology, competence, privacy, and referral were related to the aspects that, in the participants’ opinion, were valued by men in their therapeutic paths, and the χ2 of these terms (Table 1) reinforced this idea. Urology emerged as the privileged context in which men found ways to ask for help when they faced signs or symptoms of alterations, as well as privacy, seen as a fundamental condition in these situations.

I believe that, in the urology inpatient units or appointments in which they describe a dysfunction identified by the wife, the partner, or themselves, a problem already exists; it has to be talked about (P1).

I think that they do not seek help in hospitalizations, and this can be related to the lack of privacy that exists there; in appointments, there is more privacy; there is a moment just for the man and the doctor who is providing care (P9).

The words old and new were associated with the lexical conception of the class with a significance of p < 0.0001. The vocabulary that emerged in class 3, “Talking about sexual health,” accounted for 30.1% of the text data. The words at ease, subject, and talk stood out in this class, with χ2 ranging from 15.99 to 40.21 (Table 1). It grouped the professionals’ and men’s requirements to address sexual health in health care.

Some family doctors do not feel at ease, unless they are experts. They say “This is for the urology sector,” so they pass the buck to someone else (P8).

Many times there is also the question of virility, which is something hard for men to verbalize and talk about in general (P4).

Class 4, “Men’s access to sexual health care,” had 14.13% of the analyzed text data according to the dendrogram (Fig. 1). Lexical analysis of this class carried out by IRaMuTeQ software allowed a logical understanding of the forms of access and use of sexual health care by men. The most significant words in this class were urgency (χ2 = 82.16) and disease (χ2 = 55.74). The remaining words showed a level of significance for lexical connection of p < 0.001 and a percentage of 100%.

I can assure you that many times what happens is that the patient gets back to an urgency care context and does not come back to seek help; that is, there is no follow-up of any type (P1).

Sometimes we pay more attention to diseases and symptoms, the part of diseases that is more physical, and we do not have such a great knowledge in this area to contribute much more than by giving the pills that the doctor might prescribe or one solution or another (P4).

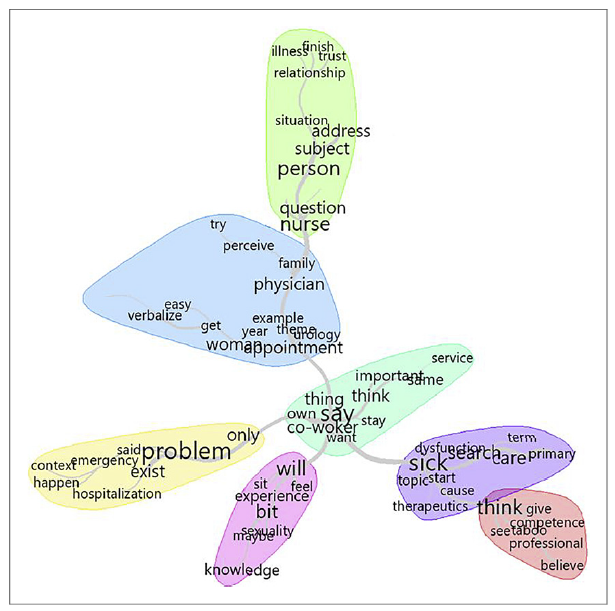

Similarity analysis (Fig. 2) showed that the main co-occurrences and connexity between the terms found in the corpus allowed the identification of three central nuclei, represented by the words problem, say, and sick. This analysis made evident the graphic centrality of the word say and its strong connexity with the branches represented by the nuclei problem, sick, and nurse.

In the problem nucleus, the branches with the highest connexity were those of the terms only and exist. These referred to classes 1, 2, and 4 and supported the idea that the search for and access to sexual health care was limited to the existence of symptoms recognized by men and nurses as requirements for access to health care.

In the sick nucleus, the branches with the highest connexity were search, care, primary, start, cause, and dysfunction. These seemed to emphasize primary health care as a gateway to health care in the case of sexual problems and referred to classes 1 and 4.

The nurse nucleus stood out by occupying a central position between two branches with relevant connexity. In one of them, the prominent words were person, question, and subject (referring to class 3), and in the other, the words that stood out were physician and appointment (referring to class 2). This positioning suggested that nurses were the mediators of men’s access to medical appointments.

In contrast to what was found in DHC, the branching between these nuclei indicated a strong connection between the interactions between professionals and men, therapeutic itineraries, and nurses’ representations about the sexual health issue, affecting the possibilities of access for men to sexual health care. Graphic analysis showed nurses’ social representations about men’s sexual health and how they are expressed in care practice.

Discussion

In “Interactions between professionals and men,” the participants who worked in primary health care highlighted two dimensions: interaction spaces and the circumstances that originate them. Regarding the former, the professionals stressed the lack of spaces intended for general and men’s sexual health and the fact that schools are privileged spaces to address adolescents’ sexual health. The circumstances that originated the interactions emphasize the appearance of symptoms or the fear of having contracted a sexually transmitted infection after unprotected sexual contact. In this area, the number of elderly men infected with the human immunodeficiency virus stood out, which according to Cardoso 13 is related to an attitude by professionals and men of avoiding addressing the subject of sexual health.

Lack of knowledge, myths, and fallacies that fill the social fabric combine with negligence, lack of time, and personal difficulties that health professionals have in addressing the subject, which results in collective avoidance that includes those who are concerned. If society disseminates the idea of sexuality that has little inclusivity for elderly people, and if “experts” do not formulate the question that this public patiently awaits for years - “How is your sex life going?” - there is a tendency for resignation and conformism to set in. In other situations, the attempt to escape conformism clashes with prejudice and discrimination, giving rise to shame and guilt 13.

Still regarding circumstances that lead to the search for sexual health care, the participants from differentiated care emphasized the increase in the number of aging-related sexual alterations, as well as those resulting from chronic disease therapies. The participants were unanimous in pointing out professionals’ prejudice and taboos related to sexual health as two of the most relevant barriers to the interaction between men and nurses. Additionally, they mentioned the overvaluing of women’s reproductive health in public policies and health care organizations, in which men’s invisibility as care recipients is identified 14,15. In this context, the study by Persson et al. 16 stands out. It analyzed the culturally prevailing and stereotyped notions of masculinity among health professionals as a barrier to adequate health care. The authors considered that professionals’ different gender notions can influence care delivery and stressed the need to address masculinity from a shared professional perspective.

In the interactions in which the terms health, sexual, man, and care were linked together, the participants also mentioned lack of training of physicians and nurses as a barrier. By studying health professionals in men’s sexual health, including nurses, Persson et al. 16 identified, in addition to lack of training in sexual health, lack of training in masculinity, and considered they influenced each other.

In this respect, what emerged from the data were the barriers to addressing men’s sexual health and their implications. Regarding the latter, there is also the fact that some of them, including sexual satisfaction, can be indications of other types of health problems, such as cardiovascular diseases, whose identification can lead to timely diagnosis and prevention of complications 17.

Men’s “Therapeutic itineraries” are delineated according to what makes them seek help, the places where it is received, and who they resort to. Old and new emerged as characteristics that influenced the closeness between men and nurses. Regardless of nurses’ gender, men seem to see being with older nurses as the proper setting for confiding about and exposing intimate problems. This can have implications for their itineraries and their access to and use of sexual health care.

Lack of privacy, which is especially relevant in inpatient services, was one of the barriers considered. Although nurses stay with patients over prolonged periods, the privacy offered by consultation rooms, where physicians are, ends up facilitating the exposure of issues of a sexual nature. However, this exposure is not always carried out by men; sometimes it is the women who accompany them to the appointments who mention the problems. Banks and Baker 18 considered that men are discouraged from using health care because many of them perceive it as incompatible with the masculine “norms” of strength and self-confidence and for fear of seeming “vulnerable,” dependent, and weak. The same authors added that men who share these beliefs can also be less aware than women of the symptoms that trigger the search for health care.

Mantiere et al. 19 identified a lack of knowledge about sexual and reproductive health as the most common barrier to men’s access to this type of care. They also concluded that religious beliefs, economic resources, and cultural gender roles, ranging from the individual to the community level, influence men’s demand for health care.

In the paths reported by the participants, nurses and family physicians emerged at times as means for men to be referred to urologists, who take on protagonism in the process of the search for care. Regarding “Talking about sexual health,” the participants considered that “having sexual health” is a state recognized by men and their sexual partners as a “good sexual performance.” From this perspective, the need to keep an image consistent with the social expectations about what being a man is, may translate into avoidance of health care supported by an alleged unwavering health condition.

Feeling at ease, or not, about addressing aspects related to sexual health, which applies to both men and nurses, was emphasized by the participants, who declared that the possibilities for men to discuss sexuality are closely connected with nurses’ training in sexual health and include their initiative in addressing the subject, as well as the availability of time and spaces for this to happen. Seymour-Smith et al. 20 added that health professionals’ stereotypes and representations about masculinity become frameworks that can restrict opportunities for men in the health care area. Robertson 21 stressed that the way health professionals understand masculinity can be as relevant as the way men do, which can imply limitations on sexual health being addressed in primary health care.

The starting point of the need to “talk” about the “subject” can be sexual problems recognized by men themselves or their sexual partners. In this scenario, women can be an important mediation element in access possibilities because they promote the link between the care, seek, sick, and appointment nuclei, facilitating closeness between men and professionals.

From the participants’ perspective, lack of privacy and intimacy were barriers to the search for care by men, usually carried out only when a problem or disease occurs. Davies 22 suggested that some men had concerns about seeking help as soon as a problem came up but preferred to resort to the Internet and telephone helplines to obtain information, which allows anonymity.

The class “Men’s access to health care” showed that men did not consider primary health care a special resource and that when sexual problems with more marked symptoms appeared, they resorted mostly to urgent care. The participants also stressed that lack of knowledge about forms of access and men’s distance from care services may be related to the absence of family doctors and delays in getting their appointments scheduled. The mentioned aspects corroborated what was described by Banks and Baker 18, who mentioned a lack of extended hours, appointment schedule systems that are difficult to use, unpredictable waiting times on appointment days, and perception of care spaces and environments as feminine as additional barriers.

Gender issues in health have received increasing attention, and scientific evidence has indicated that men and women have different sexual and reproductive needs 23, as well as different beliefs, which influence their attitudes to seek help. Despite the variations in men’s needs, it is important to mention a study by Grandahl et al. 24, which considered that promoting men’s access to sexual and reproductive health care implies a convergence of efforts by the state, health systems, and health professionals. Another relevant aspect pointed out by these authors was the need for men to be considered a target of this type of care and not be excluded from it by normative attitudes that favor women’s reproductive health.

Men’s sexual health is not grounded ideologically, clinically, or in nurses’ training, and ends up being considered “In everybody’s interest but no one’s assigned responsibility” 24, p. 1. In this context, it is important to emphasize the need for clear guidelines that make men’s access to and delivery of sexual health care intelligible to nurses. All services of primary and differentiated care can have an important and shared role in the improvement of men’s access to care and the achievement of better health results. But for this goal to be met, men must be trained to use health services and integrated into programs oriented toward preventing and diagnosing problems.

Conclusions

Sexual health is a complex and multidimensional concept. The representations influence and manifest themselves in the interactions between men and institutions, so it is fundamental to identify how they are present in professionals’ training, their practices, and the organization of health services, particularly sexual health services.

These preliminary results highlight that sexual health does not have a formally recognized space and that prevention is not considered a possibility in the circumstances that originate the interactions between men and health professionals. The barriers to these interactions mentioned by the participants were men’s and nurses’ taboos regarding addressing sexual health, lack of training of professionals in sexual health, overvaluing reproductive health, and feminization in the structuring of services, which excludes men.

Regarding therapeutic itineraries, nurses stressed possibilities in the process of seeking help: older nurses, the privacy of physicians’ offices, and the monitoring offered by partners. Men’s and professionals’ taboos related to sexual health, beliefs about masculinity, and social expectations about masculinity that condition speech stood out. Lack of space, privacy, and time for addressing aspects related to sexual health was also mentioned. Regarding men’s access to sexual health care, primary health care is not valued by men and barriers to access at this care level seem to be related to the absence of family physicians and delays in scheduling appointments.

Policies and health services show hegemony of women’s reproductive health, together with sexual health invisibility, for both men and women. In this scenario, creating alternatives for the use of sexual health care by men to become a reality, implies turning sexual health into a clear care goal and placing it unequivocally in schedules, spaces, and health professionals’ practices, including different kinds of masculinity in sexual health care, and considering different needs, beliefs, and attitudes in the process of seeking help. Addressing men’s sexual health from a positive perspective requires a convergence of efforts by the state, health services, health professionals, and communities in general.

Study Limitations

Despite the concern for diversity and heterogeneity in the selection of participants, only one focus group was considered.

Implications for Practice

This preliminary result highlights that, for men’s sexual health to be a reality, and for nurses to be able to meet this population’s needs, it is fundamental to develop proper training of health professionals in sexual health and gender that can contribute to demystifying stereotypes about masculinity. The authors suggest that the curricula of undergraduate and post graduate nursing courses should include sexual health as an area per se (without limiting their scope to reproductive health), consider men and women as subjects of sexual health care, and address stereotypes related to masculinity. At the organizational level, it is indispensable to include the approach of sexual health in health care, analyze the possibilities of access by men, give them visibility in electronic records, and consider alterations in the planning and delivery of primary and differentiated health care. Regarding knowledge production and dissemination, the present study showed the need to invest in this area so nurses’ responses to the sexual health needs of the general population and, men in particular, can be supported and made clear.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the nurses who voluntarily made themselves available to participate in this study.

Statement of Ethics

Individual written consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study before the focus group realization.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning the authorship or publication of this article. The authors state that the opinions expressed in this article are their own and not from an official position of the institutions or financial agents.

Author Contributions

Tereso, Alexandra: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review and editing, supervision, and project administration. Antunes, Lina: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, and writing - original draft preparation. Brantes, Ana: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, and data curation. Fernandes, João and Santos, Rui: conceptualization and resources. Antunes, Ricardo: conceptualization, resources, and writing - review and editing. Curado, Alice: methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, and writing - review and editing.