Introduction

Currently, diabetes affects around 537 million adults worldwide, with over 90% of patients with diabetes mellitus having type 2 diabetes (T2D) 1-3. This number is predicted to increase to 643 million by 2030 and reach 783 million by 2045 1. In 2023, the Portuguese Society of Diabetology estimated, based on the PREVADIAB study, that diabetes affected 14.1% of the Portuguese population aged 20-79 years, equating to approximately 1.1 million individuals 4. The development of T2D is related to the combination of certain risk factors, such as ethnicity, genetics, and age (non-modifiable risk factors), as well as inadequate diet, physical inactivity, lack of sleep quality, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (modifiable risk factors) 2,5,6. There is strong evidence that lack of physical activity and obesity are important modifiable factors, not influenced by genetics, that strongly contribute to the development of the disease, and therefore, the implementation of interventions that aim to improve the population's lifestyles and behaviors can contribute to prevention and delaying the development of T2D 6,7. Health literacy (HL) could be another potentially modifiable risk factor, which is defined as the set of “cognitive and social skills that influence the motivation and ability of individuals to obtain, understand, and use information, with the aim of preventing and maintaining good health” 8. Low levels of HL are related to unhealthy behaviors that increase the risk of developing T2D, such as a sedentary lifestyle, poor eating habits, smoking, and alcohol consumption 2,9,10. Most studies on HL and diabetes have focused on individuals already diagnosed with the condition. However, there is a limited understanding of how HL influences those at risk for developing T2D 11,12. In fact, some studies have indicated that low levels of HL may be linked to an increased risk of developing T2D 2,12. However, further research is essential to better understand this relationship and its underlying mechanisms. Such studies would provide valuable insights to inform the development of more effective, targeted prevention strategies. This study aims to understand whether low levels of HL are associated with an increased risk of developing T2D in the adult population living in the municipality of Leiria 12,13.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

For this analysis, data from the pilot study, Longitudinal Health Literacy Study of the Municipality of Leiria (LiSa), were used. LiSa is a prospective population-based closed cohort study that is being developed and implemented by a multidisciplinary and multicenter team (researchers, health professionals, designers, and mayors, among others) in Leiria with the aim of increasing health literacy in the coming years.

This longitudinal cohort study is designed to gather data over a period of 10 years, employing five data collection instances. Taking into consideration a random sample stratified by gender and age groups (18-29, 30-64, 65 or more), a confidence level of 95%, a margin of 5% error, and 75% of dropout rate, a sample size of 4,003 (2,001 males and 2,002 females) were determined 14. For more details on data sample calculation, consult “Study protocol for LiSa cohort study” 15. Data on HL, anxiety, depression, health characteristics, health behaviors, and sociodemographic information will be collected from each participant. The first data collection will be carried out in person, by a team of trained interviewers, and follow-up will be carried out via telephone calls. To test the established methodology, a cross-sectional pilot study was conducted in the largest parish of the municipality. Data collection took place between February 14 and March 14, 2024, using the computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) technique, carried out by a team of trained interviewers. A random starting point was established, and participants were selected using a “house yes, house no” approach. In apartment buildings, half of the households on each floor were included. In each household, the selection criteria for participants were as follows: the participant must be over 18 years of age, and if more than one adult was present, the individual whose birthday was closest to the interview date was selected. The questionnaire applied consists of sociodemographic and health characteristics questions, the European Health Literacy Survey short version (HLS-Q12), and the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) scale. The sample for this analysis consists of 175 individuals aged 18 or over. The guidelines from observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) were applied to the study design 16.

Study Population

The study population is made up of noninstitutionalized adults (18 years or older) living in private homes in Leiria. Residents of hospitals, nursing homes, military barracks, or prisons were excluded from the study. Furthermore, individuals who were unable to respond to the questionnaire (e.g., not fluent in the Portuguese language; cognitive limitations) were also excluded.

Variables under Study

In the pilot study, data on HL, health characteristics, and sociodemographic characteristics were collected from each participant.

Health Literacy

HL was measured through the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire short-form version (HLS19-Q12). The HLS19-Q12 was previously translated and validated for the Portuguese population 17. This tool contains 12 questions that measure HL. Each question evaluates the recognized complexity of accomplishing a particular health task related to health by inquiring, “On a scale from very difficult to very easy, how easy would you say it is to (e.g., understand what to do in a medical emergency)?”. Responses are recorded on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1, very difficult; 2, fairly difficult; 3, fairly easy; 4, very easy). If a minimum of 80% of items exhibit valid responses, a unified score can be calculated as a quantitative representation of general health literacy. The following cutoff points were defined 18, 19: inadequate HL: scores between 0 and 25 points; problematic HL: scores between 26 and 33 points; sufficient HL: scores between 34 and 42 points; excellent HL: scores between 43 and 50 points.

Health Characteristics

Metabolic risk was assessed using the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC). FINDRISC, originally developed in Finland, is a simple and practical tool to identify individuals at high risk of developing T2D, without requiring laboratory tests 20-22. The score is established based on eight easily discernible variables: body mass index, age, waist circumference, level of physical activity, diet, occurrence of previous hyperglycemia, hypertension, and family history of diabetes 20. It provides an estimate of the likelihood of developing T2D within the next decade. This score is being used in different European populations and allows a maximum of 26 points. The individuals are classified into different risk levels of developing the disease: low (<7 points); slightly moderate (7-11 points); moderate (12-14 points); high (15-20 points); and very high (more than 20 points) 22-24.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Data on sex, age, education level, and monthly income of the household were collected.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe participants’ sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education, and monthly income). The analysis of the relationship between the level of HL (independent variable) and FINDRISC score (dependent variable) was performed using a multivariate linear analysis. Prior to analysis, a histogram was employed to evaluate the normality of the diabetes risk score, revealing a normal distribution for this variable. The multivariate linear analysis was conducted in three nested statistical models. Model 1 represents the crude association between de FINDRISC and HL; model 2 was adjusted for age and sex; and model 3 was adjusted for the same factors as model 2 plus education level. Coefficients (β) were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The Durbin-Watson test was used to evaluate the potential presence of autocorrelation in the residuals of the regression models. Furthermore, to ensure the reliability and robustness of the model, residual graphs were constructed. All tests were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28 software.

Results

In the LiSa pilot study, 178 individuals were interviewed, of which only 175 were eligible for this study.

Participants Characteristics

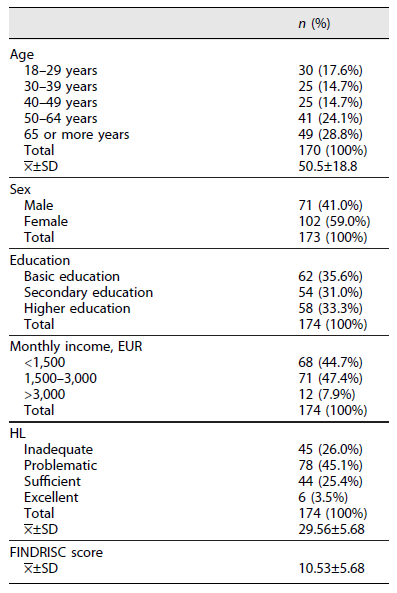

The sample consisted of 71 (41.0%) male individuals and 102 (59.0%) female individuals, with a mean age of 50.5 years (SD: 18.8). The largest number of participants (28.8%, n = 49) are aged 65 or over, with the age groups from 30 to 39 years old and from 40 to 49 years old having the lowest number of respondents (14.7%, n = 25 for both) (Table 1). Sixty-two (35.6%) participants completed basic education, 54 (31.0%) secondary education, and 58 (33.3%) completed a bachelor’s degree or higher. A large part of the participants, 68 (44.7%), have a monthly family income of less than EUR 1,500, 71 (47.4%) between EUR 1,500 and 3,000, and only 12 (7.9%) respondents have a monthly family income of more than EUR 3,000. Regarding HL, 45 (26.0%) of respondents showed inadequate levels, 78 (45.1%) had problematic levels, 44 (25.4%) had sufficient levels, and only 6 (3.5%) had excellent levels of HL (Table 1).

FINDRISC Diabetes Score

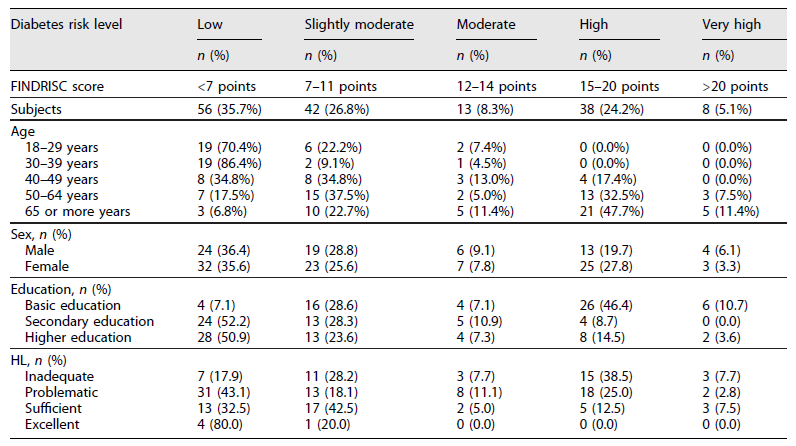

According to the FINDRISC scale, 35.7% of respondents have a low risk, 26.8% have a slightly moderate risk, 8.3% have a moderate risk, 24.2% have a high risk, and 5.1% have a very high risk of developing T2D in the next 10 years (Table 2). The results suggest that there are differences in the risk of developing T2D by HL level. Higher scores on the FINDRISC scale are observed in participants whose HL level is lower. Among individuals with inadequate HL levels, 38.5% are at high risk of developing T2D and only 17.9% are at low risk. In turn, in the group of participants with sufficient levels of HL, most individuals have a low or slightly moderate risk of developing T2D (32.5%, n = 13, and 42.5%, n = 17, respectively). All participants with excellent HL levels scored less than 12 points on the FINDRISC scale (Table 2).

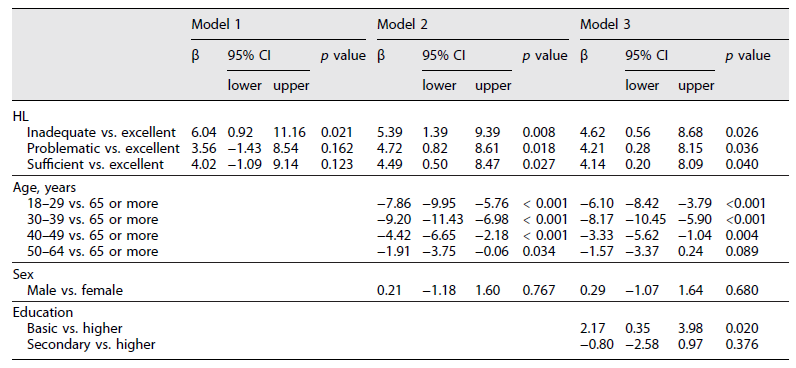

In linear regression, model 1, there was a significant difference when comparing the group of individuals with inadequate vs excellent levels of HL, with individuals with inadequate levels of literacy having on average 6.036 points more in FINDRISC than individuals with excellent levels (95% CI: 0.917-11.155). In model 3, adjusted for the other variables (age, sex, and education), the inverse relationship between the HL level and the FINDRISC score is significant in all compared scenarios (inadequate vs. excellent, problematic vs. excellent, and sufficient vs. excellent). In this final model, individuals with inadequate levels of literacy presented, in average, 4.62 points more on the FINDRISC scale than individuals with excellent levels of literacy (95% CI: 0.56-8.68) (Table 3).

Table 3 Potential influencing variables of the FINDRISC score: results from linear regression analyses

The risk of developing T2D diabetes differs between age groups (Table 2). The low-risk rate was higher in the group aged 30-39 years (86.4%, n = 19), while the high-risk rate was higher in the group aged 65 or over (47.7%, n = 21) (Table 2). In both model 2 and model 3 older ages were associated with an increased risk of developing T2D. In model 3, people aged 30-39 years had, on average, 8.17 points lower on the FINDRISC score than people aged 65 or over (95% CI: −10.45 to −5.90) (Table 3).

Differences in the risk of developing diabetes were also observed between men and women. While the high-risk rate was higher in females (27.8%, n = 25), the very high-risk rate was higher in males (6.1%, n = 4) (Table 2). There were no significant differences in any of the 2 models adjusted for this variable (Table 3).

Education level is also associated with the risk of developing T2 diabetes (Table 2). The high-risk rate was higher in the group of participants with basic education (46.4%, n = 26), the same was seen in the very high-risk rate (10.7%, n = 6) (Table 2). According to model 3, participants with basic education have on average 2.17 points more on the FINDRISC score than participants with higher education (95% CI: 0.35-0.398) (Table 3).

The Durbin-Watson test and the residual analysis confirmed that the data presented no significant pattern, indicating a nonrandom distribution of residuals in the regression model.

Discussion

In this study, 71.1% of individuals were found to have inadequate or problematic levels of HL, which is higher than the 61% reported in a national survey of the Portuguese population using the HLS-EU-PT with 47 items 20. A similar study, also employing the long version of the HLS-EU-PT, conducted in another parish in the Portuguese Alto Minho region, revealed a slightly lower percentage of individuals with inadequate or problematic HL levels, at 66.1% 25. Additionally, another study conducted between December 2020 and January 2021 used the HLS19-Q12 scale to assess health literacy among residents of Mainland Portugal. The results indicated that the majority of participants had adequate health literacy, while 29.5% exhibited inadequate or problematic levels, significantly lower than the figures found in the adult population of the municipality of Leiria 18. The lower level of HL observed in this study may be related to the higher proportion of older individuals surveyed compared to other studies. The low educational level of the sample may also explain these results.

The main goal of this research was to measure the relationship between the levels of HL and the risk of developing T2D in adults living in the municipality of Leiria. The findings are in accordance with previous studies suggesting an inverse relationship between HL levels and the risk of developing this chronic disease 2,14,26,27. This can be explained by the fact that poor levels of HL are associated with risk behaviors for the development of T2D, such as a sedentary lifestyle, incorrect eating habits, and alcohol and tobacco consumption 2. Furthermore, factors such as education level, income, and age play significant roles in health behaviors, with HL frequently acting as a mediator between these factors and the health practices adopted 28-30.

Age is one of the non-modifiable risk factors for the development of T2D, with older people tending to have a higher risk of developing the disease 31. The results of this study agree with this evidence, showing a positive relationship between age and the score obtained on the FINDRISC scale.

Contrary to what has been found in other studies, sex has not been shown to be one of the non-modifiable risk factors for the development of the disease. This can be explained by the small sample in the pilot study. Similar studies with a larger sample size might produce results that are in accordance with what is already described in the literature, that is, a reduced risk of developing T2D in women 32.

Regarding the level of education, the data show that people with higher education have a lower risk of developing T2D compared to people who have only completed basic education. These results are in line with previously published evidence, including a cohort study carried out in eight Western European countries, which revealed an increased risk of developing T2D in people with lower levels of education 33,34. In fact, low levels of education have also been linked to lower levels of HL 35-37. HL may serve as a mediator between education and diabetes risk, acting as an intermediary factor that can either amplify or reduce the impact of education on the likelihood of developing the disease. While education is commonly linked to better health outcomes, including a lower risk of diabetes, this relationship is not direct but is mediated by HL. Individuals with higher educational levels tend to have better HL, which enables them to understand medical information, follow treatment plans, and adopt healthier behaviors 2,30,38. A Danish population-based study found that HL mediates the relationship between educational attainment and health behaviors, particularly with regard to sedentary behavior, unhealthy eating, and obesity. Another study showed that when HL was included in the analysis, the direct relationship between education and glycemic control became nonsignificant, suggesting that HL fully mediates this connection 30, 38. Thus, understanding the mediating role of HL has important public health implications. Improving health literacy may help mitigate the negative effects of low educational attainment on the risk of diabetes 39,40.

In fact, HL is a necessary but insufficient condition for behavior change. Although HL plays a pivotal role in enabling individuals to make informed health decisions, behavior change is a complex and multifactorial process. Key determinants, such as personal motivation, social support, the removal of economic and cultural barriers, and the formulation of public policies that enhance health education and access to healthcare services, are essential for promoting sustainable behavior change. These factors complement HL and facilitate the adoption of healthy behaviors 41-46.

This study has some strengths and limitations. One of the strengths of this study was using the HLS19-Q12 and the FINDRISC. Both are powerful public health tools that have already been validated in multiple languages and have been used in several studies. Furthermore, they can be applied quickly and simply, including through online tools. On the other hand, the small sample size in this study may limit its statistical power, increasing the risk of type II errors and reducing the precision of our estimates. For the largest parish, the required sample size was calculated to be 573 participants. However, due to time and budget constraints associated with this initial data collection (pilot study), it was not possible to recruit the desired number of participants. Consequently, the findings should be interpreted with caution, as they may not be fully generalizable to larger populations. Another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which prevents the establishment of direct causal relationships, requiring a cautious interpretation of the results. Furthermore, in a future data collection it will be important to record other variables, such as the previous diagnosis of diabetes, and the participant’s history of chronic diseases. In the future, for a more detailed analysis, data on participants’ smoking habits and frequency of alcohol consumption should be included in the model. This study did not include these variables due to the small sample size.

Overall, some studies have already reported a link between HL and general health, including regarding the risk of developing diabetes 14,47. This study confirmed the inverse association between literacy and the risk of developing the disease. HLS19-Q12 and FINDRISC are effective tools for detecting individuals with low literacy levels and at risk of developing diabetes and, therefore, could be included in public health programs. It is important to invest in public health programs that contribute to increasing the population’s health knowledge, with the aim of preventing not only the development of T2D, but also other comorbidities. The LiSa study could be a viable diagnostic tool from a population perspective. As a pilot study, it was primarily designed to validate the methodology and provide preliminary insights that can inform future, larger scale research. We hope that the data collected in future phases will not only reinforce the evidence obtained in this initial study but also generate additional valuable insights.

Statements Anonymized

All papers must contain the following statements after the main body of the text and before the reference list.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Maria Pedro Guarino, coordinator of ciTechCare - Center for Innovative Care and Health Technology of Polytechnic of Leiria for all his support of the LiSa project.

Statement of Ethics

LiSa study has been ethically approved by the Politécnico de Leiria Ethics Committee (PARECER No. CE/IPLEIRIA/33/2022). Before registration, all participants read and sign the written consent form. A copy of the signed consent form is given to the participant.

Author Contributions

Maria João Batalha, Tiago Gabriel, Bartolomeu Alves, Ana Soledade, Rui Passadouro, and Sara Simões Dias: conceived and designed the LiSa study. Sara Simões Dias and Maria João Batalha conducted the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the current manuscript through review and editing and have approved the final manuscript.