Introduction

In a world where states increasingly use geo-economic instruments to project their strength, recent events prove that Russia remains attached to traditional forms of power. In this context, the Wagner Group emerges as a semi-state security force that uses an undefined status to operate entirely outside international law or any national legal framework to pursue Russian external interests in strategic areas.

The study starts from the following starting question: What is the role of the Wagner Group in Russia’s Foreign Policy? Its general objective is to identify the pattern of Wagner’s actions and to understand its usefulness in the fulfilment of Russia’s objectives.

In terms of specific objectives, we aim to: a) understand the concept of Private Military En- terprise (PME), b) compare the Wagner Group with other non-Russian PMEs; c) compare the scrutiny that the Wagner Group suffers compared to other PMEs; and d) identify responses of the International System to the emergence of PMEs and the Wagner Group.

1. Methodology

The research is a comparative case study, drawing on academic literature review and analysis of investigative journalism pieces from Russian and Western sources, as well as strategic and legal documents.

In order to make the comparison between the Wagner Group and other non-Russian MNEs, a qualitative content analysis was used, based on reports and studies that focus on the topic of MNEs in the case of “Western” companies, in addition to the content available on the companies’ official websites. For the Wagner Group, due to the lack of official sources, Western and Russian news and journalistic investigations were used as a basis.

To check the level of scrutiny, a quantitative analysis was carried out by first using Google Scholar to check the number of results in academic studies related to the topic. Then the Google Trends tool was used to check the level of public demand and interest in the Wagner Group and other EMPs. The data collected through Google Trends was collated and processed through Mi- crosoft Excel.

The study was conducted in the first half of 2022, during the first months of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. The information was collected until May, which was the time limit of the research.

2. Definition of Private Military Enterprise (PME)

Given the lack of consensus on the use of different terms, notably between mercenaries and private military companies (PMCs) and their employees, we aim to clarify how we understand the terms throughout the paper.

Protocol I Additional to the Geneva Conventions (2022) on the protection of victims of in- ternational armed conflicts defines the term mercenary in Article 47(2):

The term “mercenary” refers to anyone who:

a) Be specially recruited at home or abroad to fight in an armed conflict;

b) In fact, take part directly in hostilities;

c) Take part in hostilities primarily for the purpose of obtaining a personal advantage and who have actually been promised, by or on behalf of a Party to the conflict, material remu- neration clearly in excess of that promised or paid to combatants with a similar rank and function in the armed forces of that Party;

d) Is not a national of a Party to the conflict, nor a resident of territory controlled by a Party to the conflict;

e) Is not a member of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict; and

f) Has not been sent by a State that is not a Party to the conflict, on an official mission, as a member of the armed forces of that State. (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2010)

On the other hand, a private military or security company (PMSC) is understood by the Montreux Declaration as private commercial entities that provide military and/or security ser- vices, regardless of how they recognise themselves (Montreux, 2008). According to the Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance (DCAF) they are distinguished by two characteristics: their organisational structure and their motivation for providing services - “for profit rather than for political motives” - (DCAF, 2006). However, as Sinisa Malesevic notes, the concepts of EPMS and mercenaries are often used synonymously by the media and academia. The author argues that the EPMS corps operates in a completely different international system from the 15th-18th centuries, the golden age of condotta, mercenaries and privateers. In other words, the dominant weltanschauung has evolved profoundly in recent centuries towards a nationalist vision of social relations. As such, the author reinforces that members of the EMSP have been socialised and exposed to a worldview focused on nation-states from which they cannot dissociate themselves (Malesevic, 2019). Thus:

Although individuals and organizations might be motivated by financial gain, the PMSCs inexorably operate in the wider world of nation-states and as such are just as dominated by nation-centric perceptions of the world. (Malesevic, 2019)

As such, in this paper we understand that private military companies (PMCs) are defined by their organisational structure as defined by DCAF and by their financial and national motiva- tion, which distinguishes them from mercenaries. It is also added that there will be no focus on private security companies.

The national and international legal regimes applicable to EMPs are characterised by their fragmentation. At the level of national legal instruments, EMPs’ staff are subject to criminal and civil law in the contracting state, the state of operation and their home state (DCAF, 2006). In particular, in view of Art 47(1) of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, EMPs per- sonnel are viewed as civilians under international humanitarian law, which means that they do not enjoy the immunity accorded to combatants (Cameron, 2006). Thus, in International Law several instruments are applicable to the body of corporate officials namely the Geneva Con- ventions, Montreux Declaration, the UN Mercenaries Convention, the Rome Statute of the In- ternational Criminal Court and other Human Rights treaties. However, it should be noted that the Mercenaries Convention has only 37 States Parties and that the implementation of these ins- truments is extremely difficult in view of the lack of political will for it (Cameron, 2006; DCAF, 2006).

2.1. The Russian case

Russia does not recognise the Montreux Document, is not a State Party to the United Nations Mercenaries Convention, nor is it a member of the International Code of Conduct Association (ICoCA). (Swiss FDFA, 2022; UNTC, 1989). At the national level, there is no legal regime re- gulating PMS as the Russian Constitution in its Article 71 requires that any security matter is the exclusive competence of the state (Federal Assembly, 2020). According to Article 359 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the recruitment, training, financing or other material support of a mercenary, as well as his use in an armed conflict or military actions was punishable by imprisonment for a term of four to eight years, and the participation of a mercenary in an armed conflict or military actions was punishable by imprisonment for a term of three to seven years (Federal Assembly, 1996a). Thus, it is illegal to set up EMPs. However, although criminal law prohibits the participation of civilians in armed conflicts, Art. 9 of the Federal Act of 1996, which allows citizens to set up organisations that contribute to the strengthening of defence, gives room for civilians to act as employees of EMPs (Federal Assembly, 1996b).

It is also interesting to note that Article 359 defines the concept of mercenary as follows:

A mercenary is a person who acts with a view to obtaining a material reward, who is not a national of a State engaged in an armed conflict or hostilities, who does not reside perma- nently on its territory and who has not been sent on an official mission.1 (Federal Assembly, 1996a).

At least 3 attempts to amend the legislation with the aim of legalising EMPs took place: “On private military enterprises” by MP Alexei Mitrofanov, and “On private military and security enterprises” by MP Gennady Nosovko, and the last one in March 2022 by Sergei Mironov (Khodarenok, 2017; Zamakhina, 2022).. But it is important to note that Article 359 of the Criminal Code prohibiting MNEs was used for the first time against employees of an MNE in 2014 - Va- dim Gusev, and Evgeniy Sidorov of Moran Security Group. (Yermakova & Batyrkhanov, 2014). Between 2017 and 2019, 11 cases of violations of Article 359 were reported by the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, however all of them related to the participation of Russian citizens in the war in Ukraine (then located in the Donbas) from the side of Ukraine (e.g. in the “Azov”). (OHCHR, no date).

3. Russia’s National Security Strategy (2021)

The priorities of the Russian state in the security and defence sectors come from a position of victimhood in the international system and the apparent need for Russia not only to survive against immense threats, but to grow and obtain certain moral and ideological leadership. In the National security strategy of the Russian Federation (2021)they state that some states consider Russia a threat and even a military adversary. (No. 17) To quote, “the issue of moral leadership and the creation of an attractive ideological basis for the future world order is becoming incre- asingly urgent. [...] there are attempts by various states to deliberately erode traditional values, distort world history, revise views on Russia’s role and place in it [...]. There are information campaigns aimed at creating a hostile image of Russia.” (No. 19)2.

Thus the vital interest is defined as strengthening its sovereignty, independence and national and territorial integrity, and protecting the spiritual and moral foundations and preventing inter- ference in the internal affairs of the Russian Federation (No. 22). It is also implied that Russia will be the one to shape a new architecture, rules and principles of the world order (No. 23).

Fernandes (2021) defines this position of moral superiority as exceptionalism, a more radical line of thought than Eurasianism and isolationism, both to a lesser degree but also present in Russian political doctrine.

4. Russia, paramilitary groups and Wagner

As in other states, Russia’s history is marked by the use of mercenaries and other types of mi- litias. However, in contrast to its European counterparts, this use extends into recent periods of national history. Galeotti highlights the use of different paramilitary groups throughout Russian history from the Rus’ to Putin’s time. The Druzhina, the Streltsy, the Cossack Regiments and the NKVD are examples of the different groups that throughout Russian history have been used by the central government to impose its will domestically. For the author, there is a tradition of the use of political violence by the Russian state and, in this sense, its security forces are a key instru- ment. It is important to mention the complexity of the structure of these security forces and their heterogeneity, which leads to them being in constant dispute over jurisdiction, competence and under suspicion over others (Galeotti, 2013). With this in mind, one can understand the Russian view of a PMS: a paramilitary group that receives orders from the government to use force on behalf of the state (Reynolds, 2019).

Marten, on the other hand, uses the Cossacks to exemplify how Russia has historically opera- ted with highly skilled and loyal groups to advance the government’s interests, serving as a basis for understanding the Kremlin’s instrumentalisation of EMPs today (Marten, 2019).

The first thing to emphasise is that the Wagner Group is probably not the only MNE in Russia that operates in pursuit of government interests, but it is the group of which there is the most knowledge and research from reliable sources (Marten, 2019).

The particularity in the Russian case is, more than the lack of regulation, that the illegality of this type of activity allows the Kremlin to use it as a way to blackmail and maintain control over Wagner, its leaders and employees while using its services to promote its interests (Marten, 2019).

4.1. Creation of Wagner

The very idea of setting up a private military company emerged among Russian military personnel after their meeting in 2010 with Eeben Barlow, the South African creator of Executive Outcomes (The Bell, 2019).

Its origins can be traced back to several companies, including Antiterror-Orel (Tsentr), whi- ch existed between 2005-2016, Moran Security Group which existed in two variants - transport company (2011-2017) and private security company (2012-2014) and an earlier iteration of Wag- ner, known as Slavonic Corps, which engaged in a disastrous mission in Syria (Marten, 2019).

In autumn 2013, Vadim Gusev and Yevgeny Sidorov of Moran Security Group formed a de- tachment of 267 operators to protect fields and pipelines in Syria. After a month of preparation, instead of providing security, the Slavic Corps clashed with parts of Daesh, and only after six of its fighters were wounded did it retreat. The result was the disarmament of the “corps” and eva- cuation to Moscow. On their return they were met by FSB investigators3, Gusev and Sidorov were arrested and charged with mercenarism (Fontanka, 2015).

Dmitry Utkin, the man codenamed Wagner did not serve in the Russian internal forces, but in parts of the special forces of the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (GRU). He was part of the Moran team that was in Syria. His last place of service was one of the detachments of the Second GRU Special Forces Brigade, stationed near Pskov, and he is currently in the reserve as a lieutenant colonel (Dillon, 2021).

In terms of funding, the alleged leader is St Petersburg restaurateur Evgeny Prigozhin. Accor- ding to The Bell, shortly before the creation of EMPs, companies associated with Prigozhin began working with military units. Other types of state contracts included Moscow schools and hospi- tals, as well as the presidential administration. Part of the money received from the state went to its intended purpose, the other - to the organisation of EMPs, allegedly with the knowledge of the government (The Bell, 2019).

Additionally, Wagner Group trained its personnel at two camps connected to GRU’s Spetsnaz. While the original Wagner training camp was located in Rostov Oblast, it moved to Mol’kino, Krasnodar, across from a GRU facility. In February and March 2014, unidentified military per- sonnel were seen in Crimea and later in south-eastern Ukraine (Marten, 2019).

4.2.1. Ukraine

EMPs began operating in Ukraine during the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, before taking centre stage in the war in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. Operating independently or augmenting Russian regular forces, EMP personnel in Ukraine reached between 2500-5000 during the peak of fighting in 2015. EMPs played a direct combat role in Donetsk and Luhansk, as well as training separatist militias. (Katz, Jones, Doxsee, & Harrington, 2020)

Wagner Group’s combat support to the Donbas separatists was decisive in the first crucial battles of the war in the east of the country, such as Debaltseve or the Battle of the Airport. However, it is worth noting that for some authors, the group’s role in Crimea was very limited: the regular number of troops deployed was sufficient to suppress the resistance of the Ukrainian military (The Bell, 2019).

EMP units also collected intelligence, carried out sabotage and other clandestine missions, including assassinations. Additionally, within the context of hybrid warfare4, EMP-linked media (also run by Prigozhin’s companies), such as the Kharkiv News Agency, carried out aggressive disinformation campaigns utilised on the territory of the conflict and abroad, as well as within Russia itself (Coynash, 2017; Katz et al., 2020).

4.2.2. Syria

The Wagner Group was involved in various aspects, from reconnaissance and airspace con- trol to ground attacks and special operations missions. They also trained and advised Syrian army units and various Syrian and foreign militias fighting for Assad (Katz et al., 2020).

The Wagner Group played an especially important role in the second battle of Palmyra in March 2016, when the city was recaptured by the Syrian government from the Islamic State with Russian help. Apparently, Wagner Group members were even unhappy that Syrian forces were given too much credit for this victory, when in fact it was Wagner Group fighters who secured it (Marten, 2019).

EMPs personnel included contingents from Wagner Group, Vegacy, E.N.O.T Corp.5, Vostok Battalion and others. Approximately 2,000 to 2,500 Wagner personnel were present, and their annual cost was estimated at about half the official Russian military budget for Syrian operations. This implies that Wagner was useful for the Russian military to reduce the defence budget (Mar- ten, 2019).

PEMs have often been synchronised with Russian economic priorities, for example secu- ring key energy infrastructure in central and eastern Syria and key military installations such as Hmeimim Airfield (Katz et al., 2020).

Syria was an important rehearsal for the application of a hybrid model, which continues to be exported to other battlefields. The EMPs acted as a ground force with Spetsnaz-like abilities, through which Moscow could limit regular Russian military casualties (between 73 and 101 of Wagner’s men were killed in Syria) and ensure denial capability (Marten, 2019).

4.2.3. Libya

Wagner personnel trained Libyan National Army forces in ground warfare tactics and wea- pons systems and took on direct combat roles, such as in the Tripoli offensive. Between 800 and 1,200 personnel, mainly from Wagner Group, were deployed to various training sites, forward bases, key energy and infrastructure facilities, and ports, including Tobruk, Derna, Benghazi and Sirte, to provide security in early 2020. As in Ukraine, Wagner-linked media have acquired regio- nal media outlets and conducted propaganda and disinformation operations (Katz et al., 2020).

4.2.4. Sudan

Russia has used the Wagner Group to provide military and political support to President Omar al-Bashir in exchange for gold mining concessions through M Invest and Meroe Gold, companies linked to Prigozhin. Wagner provided military training and assistance to local forces (Rapid Support Forces in the Darfur region) and in January 2019, orchestrated a disinformation campaign to discredit protesters, in addition to suppressing demonstrations by violent means (Flanagan, 2019).

In March 2022, the UK and Norwegian ambassadors to Sudan, as well as the US Chargé d’affairs in the country, signed a statement accusing Russia of involvement in the illegal traffi- cking of Sudanese gold (Belmonte, 2022).

4.2.5. Central African Republic (CAR)

As of 2018, since Russia provided small arms to the country’s security forces, it has provided military and security training - mainly for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra and mining operations - for access to gold, uranium and diamonds (Katz et al., 2020; Ross, 2018).

In August 2018, the CAR and Russian authorities signed an agreement under which “mainly former military officers” from Russia, also called “specialists”, would train the Central African armed forces. Russian-linked forces in CAR do not wear uniforms with official insignia or other distinguishing features (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Thus, among the known Wagner infrastructures in CAR is the Berengo training camp, where instructors sent by Russia train soldiers of the government army. As the journalist from the Fon- tanka agency explained, it was not combat training, but a Russian language lesson. The soldiers were taught that in combat they must recognise commands in Russian; that is, the Russians plan- ned to lead the fight (Maglov, Olevsky, & Treschanin, 2019).

4.2.6. Mozambique

In Mozambique, Russia traded Wagner’s military support against Islamist insurgents in Cabo Delgado province for access to natural gas. Wagner’s troops arrived in early September 2019, but they were not prepared for the mission - they had little experience and difficulty coordinating with local forces. After significant losses, Wagner’s troops retreated south in November. Despite sending additional equipment and troops in February and March 2020, Wagner was replaced in April by the Dyck Advisory Group, a South African EMP. It is unclear whether any Wagner troops remain in the country (Katz et al., 2020).

4.2.7. Madagascar

In early spring 2018, the Wagner Group sent a small group of political analysts to Madagas- car. In April, additional troops arrived to provide security and military training, reportedly with the assistance of GRU officers. (Katz et al., 2020).

4.2.8. Venezuela

Russian EMPs have been present in Venezuela since at least 2017 to protect Russian busi- ness interests and companies such as Rosneft. In January 20196, Russia mobilised a number7 of security contractors, probably from Wagner, to provide security for President Maduro. They carried out cyber security surveillance and protection in addition to physical security (Tsvetkova & Zverev, 2019).

4.2.9. Mali

The Wagner Group followed the same pattern in Mali that it previously executed in Sudan and CAR. In September 2021, the media talked about a deal that would allow Russian operatives into Mali who would train the Malian military and provide protection to senior officials (Irish & Lewis, 2021). Upon arrival in Mali in December 2021, Wagner’s troops began building a camp outside the perimeter of Bamako’s Modibo Keïta International Airport. The presence of Wagner-

-linked geologists and lawyers in Mali also suggests that EMP personnel may eventually provide security services to Russian companies involved in mining activity, which would be consistent with Wagner Group activities in other countries. These individuals, including the director of a mining company active in CAR, reportedly explored mining sites in the Sikasso and Koulikoro regions of Mali prior to Wagner’s arrival (Thompson, Coxsee, & Bermudez, 2022).

4.3. Modus Operandi

As a central component of Russia’s ‘hybrid warfare’ strategy, PMSs provide the Kremlin with a means to pursue Russian objectives, complementing or replacing more traditional and open forms of state. Wagner’s position as an independent contractor gives him unpredictability, and offers the Russian state a valuable tool: the ability to test new environments for military co-

-operation (Katz et al., 2020; Parens, 2022).

Also of particular interest is the strong presence in African states, and the emergence of a pat- tern of action in the region. The African strategy is based on responding to requests for security assistance, with a strong ideological component: when African leaders feel that Western states have not done enough to help them. This method has been used in resource-rich countries with weak governance.

According to Raphael Parens, Wagner’s strategy involves a three-tiered approach. First, it conducts disinformation and information warfare strategies. Second, Wagner secures payment for its services through extractive industries, primarily in precious metal mining operations. Third, Wagner engages with the country’s military, initiating a direct relationship with Russia’s military (Parens, 2022).

4.4. Realisation of objectives

Through MNEs, Moscow can support state and non-state partners, extract resources, influence foreign leaders, strengthen partners, establish new military bases and shift the balance of power in out-of-area conflicts towards preferred outcomes.

As such, the Center for Strategic and International Studies characterises its actions as: para- military (training, equipping, assisting and empowering local security forces), direct combat, intelligence, protective services of local government officials and of key local and Russian energy and mining infrastructure sites (Katz et al., 2020).

Beyond denial, MRE envoys are also more expendable and less risky than Russian soldiers, especially if they are killed during combat or training missions. Recall the situation in 2004, when three servicemen were arrested in Qatar on suspicion of murdering Zelimkhan Yandar- biyev. They were only returned to Russia after Vladimir Putin’s personal intervention. After all, non-combatants do not have any kind of immunity (The Bell, 2019).

Death cases of Russian “mercenaries” are characterised by very late notification of their rela- tives, inaccurate date of death, and delivery of the body in sealed “zinc tanks” with instructions to keep them sealed. Moreover, the Russian Ministry of Defence never confirms their deaths to third parties (Leviev, 2017).

And last but not least for Russian foreign policy, even a small-scale presence can enhance global perceptions of Russian power and global influence while propagating pro-Russian narra- tives in strategic operating environments. It is possible that these structures themselves actively contribute to the spread of rumours about their activities, including intimidating adversaries and attracting business partners.

5. Wagner Group v. EMPs

With the growth of the private military company industry following the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars, there has been renewed academic interest in the study of PEMs (Butler, Stephens, & Swed, 2019). More interestingly, these conflicts have generated demand for the type of services that companies can provide: logistics, engineering, consultancy, security, intelligence, use of force and training of local forces. In addition, they have created labour supply in the sense that employees of current EMPs are often veterans of these conflicts. (Butler, Swed, & Stephens, 2019).

To proceed with the comparative analysis, we first identified some non-Russian EMPs throu- gh ICoCA members and the book The Sociolagy of Privatised Security (2019). These are presented in Table 1.

5.1. Comparative description

For formal reasons, we opted for a direct comparison between Wagner and a company re- presentative of the Western industry. To select this Western company, we took into account its relevance in the market, the diversity of services offered, the location of its headquarters and, above all, the States in which it operates, with reference to Wagner’s operations.

In terms of structure, there is no company registered under the name Wagner or Wagner Group. There is no formal recognition of its existence, either by the Russian government or any other individuals connected to the group: “(...) no one who runs it will admit to doing so (…)” (Reynolds, 2019).

In May 2022 the group was mentioned by Foreign Minister Lavrov, stating that Wagner is present in Mali and Libya for commercial reasons, emphasising that “ has nothing to do with the Russian state.” (AFP, 2022) Prigozhin completely denied the minister’s words through his press service, quote:

“I am sure that there is no agreement between the so-called Wagner and (...) Libya and there could not be. (...) I cannot know the reason why Mr Lavrov reported that fact, (...) maybe he missed something, (...).”8 (Concord Group, 2022)

However, there are direct links and evidence of co-operation between Russia and Wagner (Rácz, 2020). Constellis, on the other hand, is registered in the State of Virginia, USA and has lo- cations in numerous states, including a headquarters in Dubai (Virginia State Clerk’s Information System, 2022). The current CEO is Terry Ryan and its CFO is Richard Hozik, with the President of North American Operations being Gerard Neville (Constellis, 2022a).

At the level of services provided, Constellis has a portfolio easily accessible to the public that includes (Constellis, 2022b):

1. Security: Physical protection services, nuclear facility protection, corporate risk manage- ment, executive protection, event security, command centres, crisis and risk services;

2. Intelligence;

3. Disaster and Emergency - Response to Covid-19, Fire and other response services;

4. K9 Services: Dog training for container and event assessment, explosive and narcotics detection;

5. Training: Shooting, Personal Protection, Defensive and Offensive Driving, Medical, among others;

6. Mine Action: Explosive Threat Mitigation, Local Training and K9 Mine Action;

7. Logistics Services;

8. Engineering: Construction of basic and operational infrastructure;

9. Unmanned Aircraft Systems: Operation of UAVs for reconnaissance, monitoring and in- telligence gathering;

10. Mechanics: Manufacture, modification, inspection and repair of militarised vehicles.

As for the Wagner Group, there is no official information on the services provided and it is necessary to resort to academic and journalistic literature to survey the activities developed (Bel- monte, 2022; Dillon, 2021; Fontanka, 2015; Irish & Lewis, 2021; Katz et al., 2020; Marten, 2019; The Bell, 2019; Tsvetkova & Zverev, 2019).:

1. Direct combat as a supplement to armed forces;

2. Training and capacity building of local militias;

3. Information and intelligence gathering;

4. Propaganda and disinformation campaign;

5. Security of infrastructure and areas of strategic interest;

6. Personal security for political leaders;

7. Trafficking in goods;

8. Consultancy and strategic management.

It is important to note that the Wagner Group differs in that it is involved in direct combat and that its activities are associated with areas of Russian interest or Moscow’s political allies. There is also evidence of murder cases linked to the group (Katz et al., 2020; Marten, 2019).

5.2. Comparative scrutiny analysis

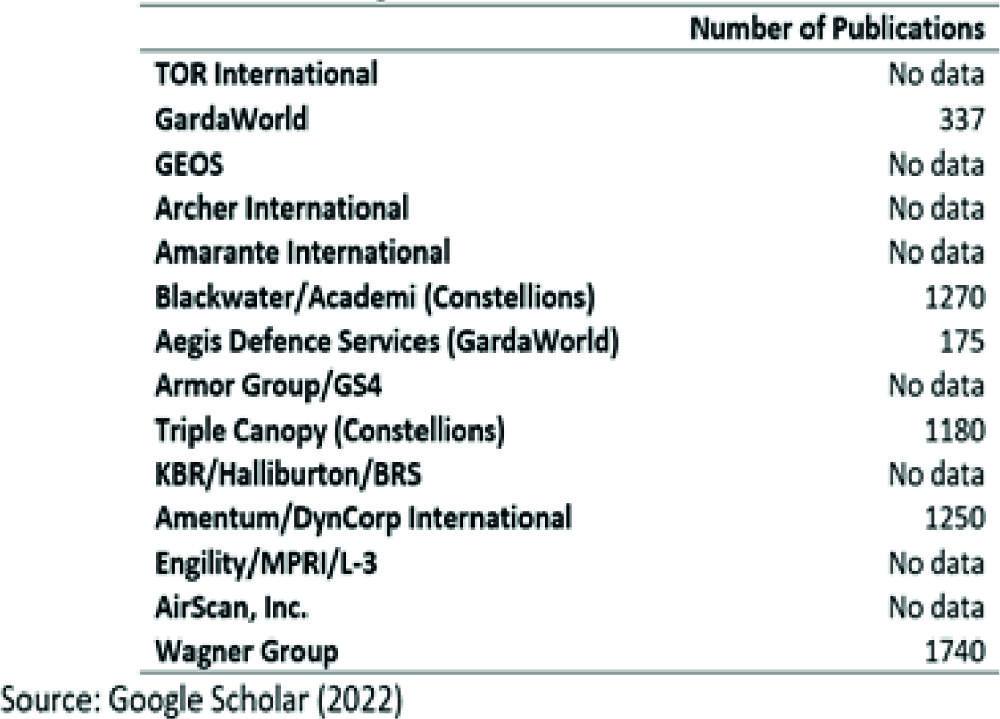

In our comparative analysis, we chose to check the number of publications realised since 2004 to the present, May 2022, on the MNEs identified in Google Scholar. The results of the search are shown in Table 2.

It is possible to observe that several of the identified MNEs have not obtained research re- sults. Thus, while it is not possible to conclude that there are no publications on them, they are certainly receiving less attention from academia than GardaWorld, Blackwater USA/Academi, Aegis Defence Services, Triple Canopy (Constellions), Amentum/Dyn Corp International and the Wagner Group. When the search is related to the topic of EMPs, seen in Table 3, it is passable the interest the topic has received through the high numbers of results. It is also added that in related searches, only two MNEs are mentioned - Blackwater USA and Wagner Group - which

correspond exactly to the highest number of publications in Table 2.

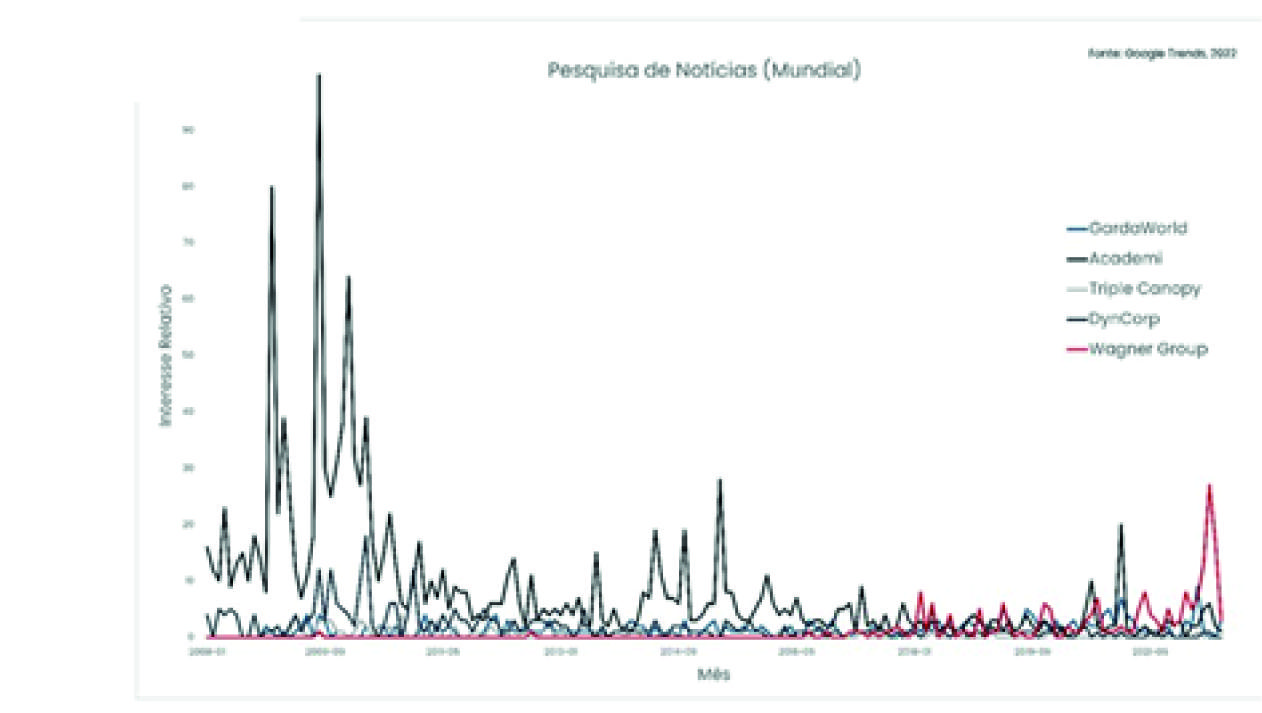

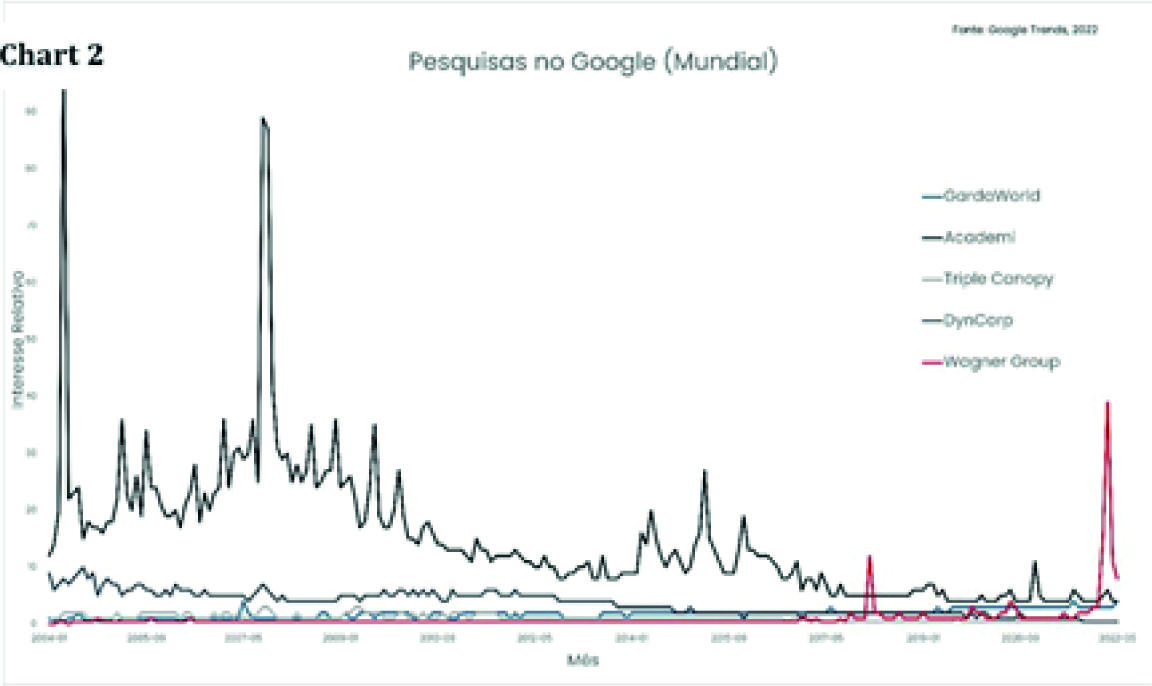

We then utilised the Google Trends tool to look at the relative Interest over time between the 5 EMPs that ranked highest in the publications - Wagner Group, Amentum/Dyn Corp Interna- tional, Blackwater USA/Academi, Triple Canopy and . The results are presented in Graph 1 for news searches and Graph 2 for Google searches, the results were obtained in May 2022.

GardaWorld

Indeed, there is greater academic and journalistic attention paid to the Wagner Group and its activities compared to other MNEs, with the historical exception of Blackwater USA, now Academi. However, it should be noted that it is possible that Wagner is under investigation by military entities that are not publicly accessible. However, the increase in general interest in Wag- ner coincides with two events:

1. Clash between US troops and Wagner members in February 2018 in the Syrian War. (Hauer, 2019; Schmitt, Nechepurenko, & Chivers, 2018).

2. Invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 (BBC, 2022; CNN, 2022).

6. International System Response to MRE

The Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance was established in 2000 at the initiative of the Swiss government and currently has 54 States Parties. The Swiss foundation takes as its mis- sion the reform of security sector governance based on international standards and established practices. To this end, DCAF takes on an advisory role in the development of national legislation of its States Parties. In addition, the fund seeks to produce information and promote its access to civil society and other private actors (DCAF, 2022).

The International Code of Conduct Association is an initiative whose mission is to ensure that EMPs or other providers of private security services respect human rights and international humanitarian law. The association seeks to create minimum standards that hold PSOs accounta- ble. To this end, it counts as members governments, MNEs and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) whose role is to monitor compliance with the standards of the code and ensure accoun- tability. (ICoCA, 2022a) It should be noted that ICoCA represents a form of self-regulation by MNEs. (DCAF, 2006).

Already at the level of the discussion on reforms in the governance of MNEs, it goes through three main pillars (DCAF, 2006):

1. Total ban on activities;

2. Creation of an international body to regulate the industry;

3. International Convention setting minimum standards to regulate the industry such as tho- se already developed by IcoCA.

However, existing International Humanitarian Law is not applicable to Wagner’s employees, as it does not fit any existing definition of either mercenaries or MRE’s as they are understood. This is because Wagner does not operate within Russian national law, its existence not even being recognised by the individuals associated with the group, nor does it operate within international humanitarian law. Therefore, the failure is not a gap in, but application of, existing international law.

Nathaniel Reynolds, senior analyst for Russia policy at the US State Department, proposes three concrete measures to neutralise the Wagner Group: First, stigmatising Wagner through a public diplomacy campaign that would focus on demonstrating that Wagner is not formally an MNE, that it operates to unacceptable standards, and that its employment entails significant risk; Second, an increase in sanctions on assets held by Prigozhin; Finally, he recommends informa- tion sharing among Western allies to better identify Wagner’s operations. (Reynolds, 2019).

Conclusion

Following the research, the first piece of information to highlight is that the Wagner Group is not an MNE, i.e. it does not have any level of institutionalisation nor does it fit into any legal or academic definition despite providing similar services.

Thus, the Group exists to conduct operations outside Russian territory in pursuit of state in- terests and utilising plausible deniability policy externally and internally. To this end, the Group carries out activities ranging from training local troops, intelligence gathering, protection of are- as of interest and political leaders to direct combat. These characteristics differentiate it from what would be an EMP because they often do not have such a direct link with the governments and states of which they are nationals. In this sense, the Wagner Group acts by promoting allian- ces with Moscow’s partners and protects Russian economic activities on foreign territory. It is important to mention Wagner’s conjunction with disinformation campaigns, or even the use of its presence as a power narrative.

Considering that the group does not formally exist, and its activity is illegal in Russia, it is difficult to see how central Wagner is in Russian foreign policy since it is not integrated into official Russian strategic plans. However, it is clear that the Group has a relevant role in Russian foreign action.

At the international (Western) level there is an incorrect association of Wagner with EMPs and mercenary groups, as observed in the quantitative search engine analysis. The confusion itself makes it substantially more difficult to neutralise the group’s activities, as there is no clear idea of its nature. This is because all initiatives to regulate MNEs, even if successful, do not reach Wagner and her staff as they presume an institutional structure that does not exist.