Introduction

Ukrainian territory for centuries was the stage of battles, divisions, invasions, and different alignments, imposed or masked willingly done.

Only in 1991, with the dissolution of the USSR, Ukraine became an independent country. It would remain, as we will see throughout these pages, the stage for the ideological battle between East and West.

This article tries to draw the path that Ukraine has been treading since its independence and how Russia has been trying to interfere and to influence the political, military, economical and ideological future of the country.

Supported and analysed through the lens of realism and critical geopolitics, we will roam through some of the meanders that pushed both countries- Russian Federation and Ukraine- to the invasion perpetrated by the first and how Ukraine got to the point they are now.

On what concerns realism, many thought that after the end of the Cold War this theory would lose momentum. The battle between blocks and ideological influence had reached an end. The constant state of belligerency between the Western-Eastern worlds was gone. With the end of the Cold War, the USSR also reached its finitude. The ex-republics started their own journey, some of them under the umbrella of the Russian Federation, while others started to commune with the western world.

But this communion would bring lots of issues to the Russia Federation and to their imperia- listic aspirations and sense of belonging.

Here, is where the lines that realism never lost its momentum, can start to be drawn once again.

We are at the point where we can ask ourselves if the logic that fed the bilateral system throu- ghout the Cold War is really gone. Aren’t we all still assisting to an ongoing battle between ideo- logies? A permanent state of competition between nations, especially those aligned with eastern or western values? Will Ukraine be the new ‘Iron Curtain’ of the 21st century? Will it end up being divided between East and West?

As Mearsheimer wrote in his book The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (2001), the Interna- tional System is still an aggressive realm where states play to keep their power. Their main goal is not to augment it but to maintain it and to keep the balance of power (Snyder, 2002, p. 151). According to the author, the optimistic view that with the end of the Cold War the world would be able to achieve a period of peace was utopian. Carr considered this idealist view of the inter- national system naïve. War is a mean and peace cannot be achieved when so many actors play together (Korab-Karpowicz, 2017). As written by Nye, the anarchic system urges and propels sta- tes to assure their own security. States are then led to take actions towards their rivals or against actors that might menace the status quo (Nye Jr, 2004, p. 15). Morgenthau has similar views to Carr. Power embeds human existence and states, what drives them to logic of the competition for dominance and self-interest (Korab-Karpowicz, 2017). For the offensive realists, the desirable outcome is to become hegemonic, “the only great power in the system” (Mearsheimer, 2001, p. 1) (Snyder, 2002, p. 152). However, this hegemony is unlikely because “the world is condemned to perpetual great-power competition” (Mearsheimer, 2001, p. 1).

In the last thirty years of Russian-Ukrainian relationships, we can clearly draw the line of realism and realize how the fear of having a change in the balance of power (that both would find preferable), led them to this last consequence: a war of influences, ideologies, borders, and sense of belonging.

This ongoing attempt made by Russian forces to gain territory or to take control over it in Ukraine, can be better understood when considering geopolitical factors. In the light of critical geopolitics, it is also of a great value to consider Ukrainian territory as a part of the great old empire: the Russian Empire.

As Sherr puts it:

Russia’s geopolitical traditions are at least as old as these civilizational ones. The concepts of buffer zones, spheres of influence and the limited sovereignty of neighbours became central to Russian geopolitical thinking in imperial times, and these building blocks of security have retained their place in the post-Soviet era. Russia’s military establishment defines thre- at in terms of proximity; security is equated with control of space (irrespective of the views of those who inhabit it) and uncontested defence perimeters. (Sherr, 2017, p.18)

We must look carefully into History that plays a big role on what came to be one of Russia’s aspirations, a new era of Imperialism, backed up with what seems to be a new period of russifi- cation.

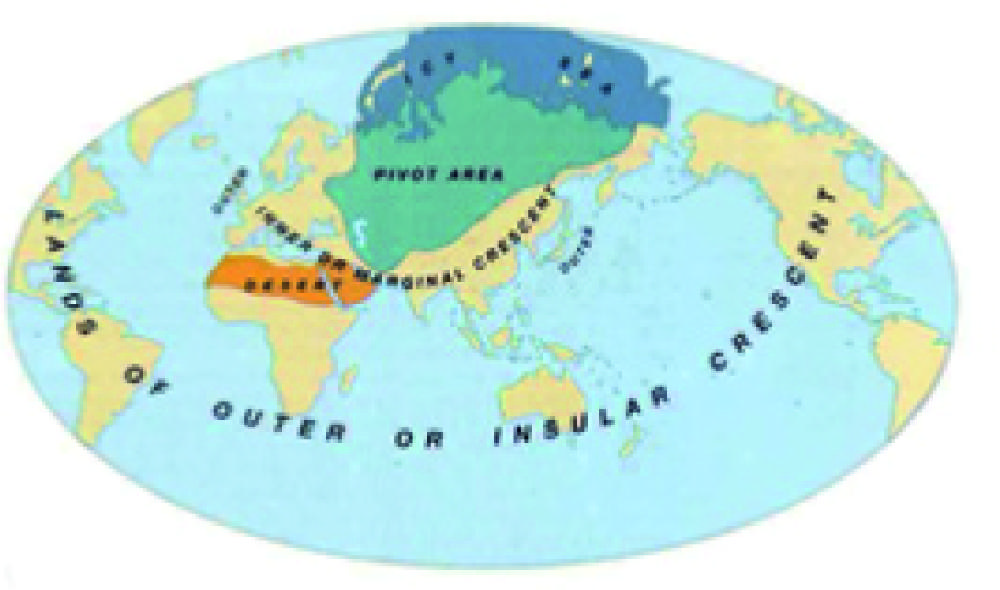

Also, when taking into consideration Mackinder Heartland theory (Fettweis, 2000) it is no- ticeable that the Russian Federation is looking after the old frontiers of the Old Russian Empire and to the ex-satellites of the USSR to take advantage from them.

According to Mackinder map, Ukraine has more than appealing reasons to have been facing a vast array of disputes and conflicts over their territory. Ukraine is at the center of Heartland (along with Russia) and has a part of the most envied Inner Crescent. The Heartland and the Inner Crescent together, would turn Russia, at the light of Mackinder’s theory, a great potency in the world, both on land and sea. And, according to another geopolitical theorist, Spykman, as we can read on Arise’s article (2021) his theory was based on the idea that: “Heartland appeared less important than the Rimland” and that “who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia, who rules Eura- sia controls the destinies of the World” (Arise, 2021). Russia still cherishes the Eurasia project to become the ruler. This idea was even taken further by Medvedev on a declaration made in April 2022: ““The goal is for the harmony of future generations of Ukrainians and the opportunity to build an open Eurasia from Lisbon to Vladivostok” (Tass, 2022).

As Russia became more alone throughout the years, seeing the West (also comprehending NATO) getting closer to its borders, triggered harsh responses that some wouldn’t predict.

So, taking into consideration both realism and critical geopolitics as theories when analysing this ongoing play, in the following pages we will analyse how Ukraine became the chessboard and sometimes even a figure of Russian intentions.

1. Ukraine in the Aftermath of USRR Collapse: Rocky Presidencies

After years under the USSR umbrella, in 1991, Ukraine declared its independence. Although it was expected for the country to thrive, the path ahead was going to be rocky. The two main and major tasks of Ukraine as an independent country were the economic development and the strengthening of their judicial and political systems. This would, ultimately, lead them to the construction and permanence of their country.

But this hasn’t come easy. It still isn´t.

Along with its independence, Ukraine was thrown into an economic crisis that, along with the established and systemic corruption led to an overall dissatisfaction among the population.

Leonid Kravchuk, member of the Communist Party, was elected the first president of Ukrai- ne. Kravchuk faced major issues: an economic crisis and a serious constitutional problem. The government was also internally shattered between the ones with an agenda for an independent and reliable Ukraine and the ones with a pro-Russian agenda (Wolczuk, 2001, pp. 103,106)

In 1994 new presidential elections took place. Leonid Kuchma became the second president of Ukraine. Having started in 1992 as prime minister, the chosen technocrat was in the row of the liberal social democrat alliance New Ukraine (p. 113) and in opposition to the weak and dubious leadership of Kravchuk. As Kuzio wrote “the period from 1994 to 1998 under Leonid Kuchma has been one of consolidation” (Kuzio, 1998, p. 1). It was also a period in which Ukraine tried assertively to portray itself as a free and independent country, ready to start establishing their go- vernment and to tackle internal disputes to turn the country more attractive and befitting West/ EU values. Kuchma took another mandate in 1999 but it started becoming more evident the Rus- sia had a major influence over his presidency. The second term for Kuchma didn’t have the same support from the Ukrainian population and that would become evident in the 2004 presidential elections. The new elections of 2004 opposed the pro-Russian candidate, Yanukovych against the pro-European Yushchenko. Yushchenko was one of the most prominent pro-western politicians being targeted by the Russian influence in Ukraine (Kuzio, 2005a). Russia set the perfect scenario to discredit pro-western politicians leading to a perfect storm. Things got even grimier when they poisoned Yushchenko in September 2004 and, in November 2004, during the second round, Yushchenko and Tymoshenko were victims of a bomb attack.

At this point and realising all that was being done to undermine fair elections, Ukrainian citizens wanted to put an end to the constant threats being posed by Russian interference in the elections. As Kuzio puts it, what happened in the year 2004, was a “clash of civilizations” (2005b, p. 35) for the future of Ukraine. Or Ukraine’s future would be European or Eurasian/Eastern; this was what was at stake.

2.1. The clash of and for Ukraine: Orange Revolution and Euromaidan

The results of the 2004 presidential elections in Ukraine were the turning point for the country’s population. Prime Minister Yanukovych’s victory wasn’t considered legitimate, and a new round would take place in December.

Meanwhile, in November, and due to a highly unsatisfied population, the world saw a major popular movement arising, which came to be known as the Orange Revolution. This move- ment, headed by civilians, intended to stop the ongoing boycott of fair elections and to shout out against the rotten prevailing system (Karatnycky, 2005). By the end of these protests, Yushchenko won by a large margin and the voting was considered fair.

Along with this new presidency, more comprehensive talks started regarding a broadening partnership between Ukraine and UE, not only economically but also politically, leaving behind any negotiations with Russian Federation.

EU saw the protests as a strong sign that Ukrainian population were making a standpoint against Russian influence and were eager to share stronger and meaningful ties with the western countries.

Therefore, EU reinforced the economic ties that have started in 1998 with the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement. This agreement between EU and Ukraine had at its core the econo- mic relations between both but also highlighting matters of democracy and human rights field.

So, in March 2007, under Yushchenko presidency, negotiations for the replacement of the old partnership began. The Association Agreement (AA), the new political partnership taking form would also include the chapter Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA)1, an ambitious partnership for the development and homogenization of trade, their laws and eco- nomic cooperation of Ukraine under EU parameters/standards (Spiliopoulos, p.257). Although the basis for this partnership began taking shape, a lot of work would still have to be done by Ukraine to fit all requirements established by EU, especially deep reforms of their political, legal, and economic systems.

Yushchenko’s presidency was going to be difficult. This presidency was marked by the no- torious friction with the parliament, and it resulted in a back and forth between the three main figures: Tymoshenko, Yanukovych and the president himself. In January 2010, new presidential elections showed precisely how weak Yushchenko had become to the public opinion. The main race was now between ‘two poles’: Tymoshenko and Yanukovych. The eastern region of Ukraine voted for Yanukovych while the western voted for Tymoshenko. This time, Yanukovych won, and no signs of forging were raised by international observers. However, his presidency started being regarded with doubts. He started new agreements with Russia and gave a step back in the conversations about joining NATO. These years were regarded sceptically not only by civilians but also by politicians (Britannica).

And, again, in 2013, Ukraine was on the verge of another uprising: the Euromaidan Mo- vement. This movement grew to riots in Kyiv that started being violently dismissed by police forces. This time, what led to the overall dissatisfaction of the Ukrainian population was when conversations between Ukraine and EU to settle an economic/political deal sank. In November 2013, the Ukrainian government should have signed the Association Agreement but, besides not having fulfilled all the requirements needed to sign it (the reforms needed on the judiciary, political and economic field weren’t yet aligned with EU parameters), Russia did a counteroffer of a deal with Ukraine, a loan and to be a member of the Customs Union. The AA-DCFTA was regarded as a hope for Ukrainians for a better future with the goal of having the EU as a partner. This culminated with the impeachment of Yanukovych that fled the country.

In all this turmoil, and to destabilise the country even more, Russia inflated the pro-Russian movements in Crimea into a bold movement to seize control over that region.

2.2. Crimean Ongoing War

Crimean parliament, in March 2014, voted to join the Russian Federation, a decision that was backed up by Russia but disregarded by the West since the voting process was considered unfair, forced and against the Ukrainian Constitution (BBC, 2014).

This was officialised in March when Vladimir Putin met with Aksyonov and other represen- tatives of the region to sign a treaty that approved the integration/incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Federation that ended up being ratified on 21st march (Reuters, 2014).

After this, an array of other ‘invasions’ took place in the cities nearby Ukrainian -Russian borders. Russia’s military started taking control of other cities: the region of Donbas was heavily bombarded and Kharkiv was also the stage of violent fights. Mariupol, Slovyansk, Kramatorsk, Odessa were also stages of pro-Russian attacks. In May 2014, the cities of Luhansk and Donetsk declared their self-separatist governments (Ray, 2014).

In the middle of all this, the presidential elections of 2014 scheduled for 25th of May, gave the victory to Petro Poroshenko while violent combats were still happening in the east trying to dis- rupt the voting day in those regions. Poroshenko took his place in early June and his first action was an attempt to restore the peace in the east as he proposed a cease-fire with the separatists (Ray, 2014). At this point, President Poroshenko, while issuing that Russian troops invaded their territory, went to negotiations and that led to the signing of Minsk Agreements2 for a cease-fire, on 5th of September, between Russia, Ukraine, and separatist leaders. The violence decreased but it didn’t stop completely. Since the Minsk Agreement wasn’t being respected by none of the par- ties involved, they decided on a second Agreement, signed between Russia, Ukraine, France, and Germany in February 2015. This was again an agreement pushing for peace in the region, trying to stop the violent fights and the withdrawal of heavy weaponry and of any foreign troops. But further events revealed that this agreement wouldn´t be accomplished either.

In November 2018, Russian special operations took another level which led Poroshenko to declare martial law in some regions (Wires, 2018). The president went to the United Nations and the General Assembly approved a resolution for the withdrawal of Russian forces from the Ukrainian territory, “condemning the militarization of Crimea, the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov” (UN, 2019). This resolution was dismissed by Russia which continued their occupation in Crimea with their military presence and seizing other cities.

Even though these actions granted some sympathy, it wasn’t enough to dissolve the veil that had fallen at Poroshenko presidency, when he was caught in the release of the Panama Papers3.

In the presidential election in March 2019, Ukraine decided for a new politician, previously known as comedian and actor, Volodymyr Zelensky, that had taken the fight against corruption as one of his key fights for his presidency as well as the peace in the east. He started his presidency on 20th of May 2019.

What Zelensky proposed himself to do on his mandate was becoming harder with every day. The conflict in the Donbas region remained and Zelensky´s intention to diminish oligarchs influence and power were now under threat, since they were the ones helping to perpetuate the invasions in eastern Ukraine.

The tensions were building up and in October 2021, Russian troops started positioning on the borders with Ukraine. Movements were also seen taking place in Belarus, in the separatist regions and Crimea.

In February 2022, it was evident that Ukrainian territory was sentenced by Russian forces. To put an end to this offensive, the western leaders discussed with Zelensky and Putin what could be done to achieve an agreement and Putin tried to force the backup of NATO from Slavic countries as he considered it a menace to their security (Aljazeera, 2022). As this was rejected, as a respon- se, Putin declared his recognition of the independence of Luhansk and Donetsk (DW, 21) and the so called Russian special military operation started on 24th February and lasts until present.

This invasion reached its one year in late February 2023.

The western world has been backing up Ukraine, not only economically but also militarily and humanitarian support/aid is being given.

As retaliation, political European leaders managed an array of sanctions aiming to attack the Russian economic system and turn them into an unfriendly state. USA has also been playing a major role on the help to Ukraine which isn’t a great surprise.

Russia, on its turn, has been let alone in the international system, relying on a few like China, Belarus, and Iran.

Russia is still fighting and destabilizing Ukraine. Not willing to give up on any or some gain, keeps perpetrating daily attacks, on an endless back and forth on the terrain.

War crimes being reported, thousands of civilian casualties on a war that has been mobilizing the world as it didn’t happen since the end of the 2nd World War.

Until now many were the losses, and a lot is at stake.

2. Ukraine: The Eastern “Borderland” Russia Seeks to Seize Influence Over

Strategically, Ukraine borders are Russia’s European gate. Not only having these gates to Eu- rope, but Ukraine has also the Inner crescent. It has important harbours much appreciated for an economical and military Russia’s strategy. Embedded in Putin’s vision, Ukraine is one of the last, if not the last, strongholds to maintain his influence and power to perpetuate his ongoing ‘war’ against the West and more profoundly, against US and NATO. Mearsheimer (2014) refers that the West and NATO teased the Russian Federation mentality/modus operandi when they ‘annexed’ Poland and Baltic countries on their sphere.

The tensions being waged in Ukraine are a demonstration of what the author Zhurzhenko mentions in her article, the concept of “two Ukraines’ ‘ (The Myth of Two Ukraines, 2002). This idea revolves around the failure of Ukraine to build a stable and strong nation state, a Ukrainian one, without external influences and pressures. Like Malyarenko and Wolff (2018) describe, Rus- sia plays the “logic of competitive influence seeking” (p. 195) that, at the author’s interpretation, is done by trying to create an unstable and unreliable environment on the Ukrainian side. These preferred outcomes would be much more suitable for Russia’s intentions over Ukraine, because an unstable and unfriendly neighbour would give them the perfect rhetoric for their claims. But, as the authors also put it, the worst outcome would be a “stable and unfriendly country”. (p. 203)

The truth is that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, many treaties took place between Russia and Ukraine. As shown by McDougal (2015), the treaties (p. 1866) were about each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. Economic matters were also discussed, being the most im- portant, the continuation of the usage of Russia of the Sevastapol naval and military bases.

But the invasion of Crimea changed the game.

The year 2014 shows how desperate Russia was to keep their feet in Ukraine and try to under- mine the peace and stability of the country. Realising that Yanukovych was losing his momentum and was about to leave the government, Russia tried to disrupt the feeling of the populations in the region of Donbas and Crimea, two of the major pro-Russian strongholds: “By invading and annexing Crimea, Russia turned the tables. It re-established its relevance and, in the process, transformed the balance of power in the Black Sea” (Sherr, Geopolitics and Security, 2017, p. 18). McDougal refers that Russia “intentionally modified the borders” (p. 1866) of Ukraine and the world watched perplexed and mesmerised at first to this military move. Russia had little to argue to back up their aggression to a neighbour and sovereign country. Besides arguing that they were defending the “ethnic russian population” (p. 1886) on that regions and that they were deploying military assets for humanitarian purpose. They also argued, as McDougal wrote, “that it had the permission of President Yanukovych to enter the country to protect the citizens” (p. 1847).

Treisman also considers that this annexation was also emotional and based on fear: “Putin’s seizure of Crimea appears to have been an improvised gambit, developed under pressure, that was triggered by the fear of losing Russia’s strategically important naval base in Sevastopol” (2016, p. 48). Treisman shares the vision that with this invasion, not only Putin was showing the image of a “defender” (p. 48), but he is also showing the world his intentions of stopping NATO’s expansion and seizing to control some of the territories that belonged to the old Russian Empire. To tackle it prior to any unpleasant surprise, Russia decided preventively to remember “those who are seeking to join Russia, particularly in the eastern regions (including Crimea) to encourage them to initiate a reunification with Russia” (McDougal, 2015, p. 1866).

For this reunification, Bobick and Dunn (2014) agreed that supporting separatists in those regions has been the way Putin tries to keep his influence but also an atmosphere of fear that grants him some respect.

Barrington and Herron (2004) also make an interesting point when they divided Ukrai- ne in regions to allow us a better understanding on Russia’s movements. They pour over the division of Ukraine in regions and therefore, some significant differences between them (lan- guage and ethnicity) what creates the gaps for Russia’s purposes. They have designed the divi- sion of Ukraine into “regions frameworks” and, as a matter of relevance, we will look into his “eight region frameworks”: “we consider an eight-region option for Ukraine given the country’s economic development patterns, divergent historical experiences, and demographic features.” (Barrington & Herron, 2004, p. 57). The regions are divided in: East (Donetsk and Luhansk); East-Central (Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia); North-Central (Poltava, Kirovohrad, Cherkasy, Kyiv, Chernihiv and Sumy oblasts and Kyiv); Southern (Kherson, Odesa and Mikolaiv provinces); Krym and Sevastapol; West-Central (Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Khmelnytskyi, Rivne and Volyn); Southwest (Chernivtsi and Zakarpatia) and the last region is the West, comprising Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk.

Regions on the East are far easier to influence, and they have already a higher rate of Russophones due to their proximity to Russia. This allowed Russia to make their moves according to the places they might get more support from. East and Southern regions are now their major focus.

Also, on the Chatham House Report, the author Sherr (2017, pp. 10-23) gives us an idea on how Russia viewed those territories in Ukraine. They saw them as bastions of their war. These populations would be the ones helping Russia to overthrow any sense of political stability and national union.

Russia, via the annexation and recognition of those separatist areas as independent states or only by showing support has been the way through which they try to control the region, “not a full-on military invasion but only a creeping occupation and subsequent takeover of strategic positions in the breakaway regions-constitutes a new form of warfare.” (Bobick & Dunn, 2014, p. 406)

3.1 Russia´s Aspiration: The Older New Empire

“Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be an empire, but with Ukraine suborned and then subor- dinated, Russia automatically becomes an empire” (Brzezinski, 2013).

Galtung (1971) explains that the theory of imperialism has its root cause on the unbalanced power among nations that are divided between Centre and Periphery. Upon this idea, imperia- lism is then the establishment of inequality relations between countries, on which the Centre will exercise power over the other (p. 81). As the author puts it, Centre is then the “mother “country” (p. 92).

Russia is the mother land willing and craving to have back all of those ‘cubs’ that were lost with the dissolution of USRR and, with this, become again the great power that once it was.

The history of Slavic countries can’t be denied, and it must be accepted as having close ties and similar paths. Authors like Kuzio (Kuzio, 1998, p. 8) trace back russification policies. For more than one century (1860-1980), these policies helped to forge a closer tie and a more embe- dded sense of belonging between the two countries. Homogenization was a key goal for Russian Empire. In Russian imperial times and also as the leader of the block of socialist soviet republics, Russia tried to alienate from the other nations their identity and character. The measures waged and undertaken focused on turning the Russian language and culture the main stronghold to unify those countries by bounds of history, heritage, and a common feeling of belonging.

In the case of Ukraine, Kuzio also refers that since the imperial times of tsars, Ukraine has always been seen as a belonging territory and all have been showing the fear of “‘losing’ Ukraine” (Kuzio, 2020, p. 90). Kuzio also points to the fact that Putin always saw the Russians as a “superior cast” (Kuzio, 2020, p. 92) and sees Ukraine and Belarus “‘fraternal’ Slavic and Russian Orthodox ‘civilisation’ stretching from ‘Kievan Russia’ (Kyiv Rus) to the present day” (p. 92).

Immersed on imperialistic ideology, we can grasp a bit further Russia’s moves towards Ukrai- ne. As Motyl put it: ‘‘Ukraine is an artificial state with no right to exist,’’ except to be part of the hegemonic empire that (Putin) seeks to build in the ‘‘near abroad.’” (Roberts, 2017, p. 44).

If so, if Ukraine can only exist as part of the Russian empire, then Kappelar points correctly to the possibility of a new period of “reunification”, the periods referring to the times when Russia and Ukraine got ‘united’ throughout their history (Kappeler, 2015, p. 112). This only comes to show how willingly Russia/Putin is to recover the past status it once had.

Bobick and Dunn (2014) discuss the intentions of Russia when emerging themselves in the conflicts at their nearby border countries. Hidden behind demagogic rhetoric, Russia has been pushing these countries to the “equivalent of vassal states’’ (Bobick and Dunn, 2004, p. 410). For the authors:

It is a miniaturised Cold War, in which frozen conflicts in small-even tiny-regions beco- me levers with which Russia can undermine Western political ideologies, challenge unipo- lar superpower rule, and alter its geopolitical standing with the West. The extremity at-large caused by these entities, internalised by their inhabitants, is perhaps the ultimate goal of Russian actions: to wage war by maintaining peace in a conflict in which Russia is simulta- neously provocateur, enabler, aggressor, and peacemaker. ( Bobick and Dunn, 2004, p. 410)

According to the authors, the neighbouring countries of Russia might face the consequences of this renewed imperialism wave from the Russian Federation. These “near abroad” must sort out new ways to deal with such an aggressive state. They also point out the Jakob Rigi strategy ““the chaotic mode of domination,” an emergent form of sovereignty that blends spectacular displays of state power with coercive force in new and frightening ways.” ( Bobick and Dunn, 2004, p. 410).

Russia’s policies towards their neighbour countries have been the one of exercising and exu- ding influence. In what comes to Ukraine, and as Malyarenko and Wolff (2018) put it, an array of measures from hard and soft policies can be used to maintain a reliable situation for Russia to gain status as their ‘friends’ (p. 193). What they try to do is undermine western influence over a neighbouring country to contain any possible direction for the future of Ukraine. By exerting control and influence over the “near abroad” allows Russia to re-emerge at the International Sys- tem as a strong player, capable of maintaining the East under their influence and, in this case, “… to keep Ukraine in its imperial strategic realm and tries to prevent the integration of Ukraine to EU and NATO”. (Kappeler, 2015, p. 110)

Vladimir Putin deeply rooted the idea that the West tries to alienate their position at Eastern Europe, he relies on historic rhetoric to justify the acts he took against Ukraine (Drost, 2022).

In Russia’s / Putin’s mentality, they need to force the Russian identity over the “near abroad”, using the ethnic and cultural bound. (Roberts, 2017, p. 39). According to the author, Crimea is seen by Putin as a territory that needs to return to the “motherland”, not to seize their land, but to restore “Russian leadership among ethnic Russians” (p. 40). Robert also reinforces this idea; he refers that the West has been provoking Russia’s reactions towards Ukraine because they are triggering their sense of vulnerability and the “fear of Western hegemony” (p. 30). According to Bank, this fear steams from the fact that without support of neighbor countries, Russia might lose the race. “Russians are inherently imperialists” (Blank, 2014, p. 15) and with this mindset Russia has been increasingly pushing and asserting for the recognition of their power (p. 17). Starr and Cornell have a similar idea, that Putin´s project is to reunite all the countries that once belonged to Soviet Union and lead their destiny (2014, p. 6). For them, the West shouldn’t have disregarded when he said that his goal was to turn Russia into a “great power” again (p. 9).

Due to his past, Putin has brought back the KGB mentality and the grandiosity of Soviet Union.

Szénási calls attention to the important role that Russia plays nowadays, and that Russia’s view of the world politics was always misunderstood by the West: “Russia acts as a great power with imperial ambitions and regained self-confidence. Russian imperialism utilises her capabilities with increasing efficiency. Any attempts to force Russia into Western subordination are fundamentally mistaken Western policies” (2016, p. 220). Motyl refers that we could be facing a “cold peace” in case Russia keeps their actions towards Ukraine (Motyl, 2014, p. 59). In his opinion, the isolation that Russia might face from this “civilizational clash” is regarded by the Federation as “a declining West and a resurgent Russia” (p. 62).

Is this “old Russia” capable enough to alter the status quo of world politics?

Conclusion

Since the end of the Cold War, the battle between West and East has never been as latent as now. The old logics of power came in full force to the twenty first century and especially to the eastern regions of Europe.

Two nations are at stake. Ukraine, looking forward into future and the Russian Federation holding to the revivalism of its history. Still grieving for the dissolution of Soviet Union, Russia wants its empire back and to be the commander of Eurasia.

The independence of Ukraine has been a sensitive subject to Russia. Russia sees Ukraine as part of their world, as part of a cultural and territorial heritage that they wish to reborn. This idea has been turning Ukrainian independence into a slippery and dangerous path. Along these last thirty years, Ukraine has been undermined by Russian influence on their internal spheres. Managing to step in Ukraine political decisions by corrupting politicians, Russia has been the majorly responsible for the setbacks on Ukraine’s path. The balance of power in that region must be assured by Russia and its allies.

But, as all other sovereign countries, Ukraine has the free will to choose its own future and choose the path for their development, either by engaging in closer ties with European institu- tions, or to decide to align as a member of NATO.

Russia would never, and didn’t accept this willingly, believing that Ukraine’s decision to join the ‘western block’ would strongly damage their geopolitical ideas for the Eurasian Project, a block that Putin desires to be the counterbalance to the west.

Settled on these premises, Russia keeps stepping boundaries.

For the near future, unless some gaining is achieved by Russia, there is a high possibility that this war will continue in Ukraine as a frozen conflict.

The securitization ‘game’ will continue to be played on the board, no winning moves. Dema- gogic rhetoric will continue back and forth, being hurled at each other.

This war is still ongoing. Much to be seen. But Russia wont’ be the same again, neither will Ukraine.

What will unfold?