Case report

A 37-year-old, female patient, phototype IV, working as a dressmaker, reported a pigmented linear lesion on the first right finger for five months, that progressively suffered a color change and increase in diameter. She reported no local trauma, other associated symptoms, or family history of melanoma.

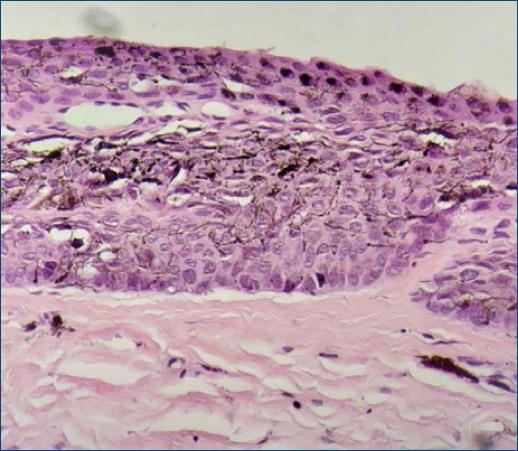

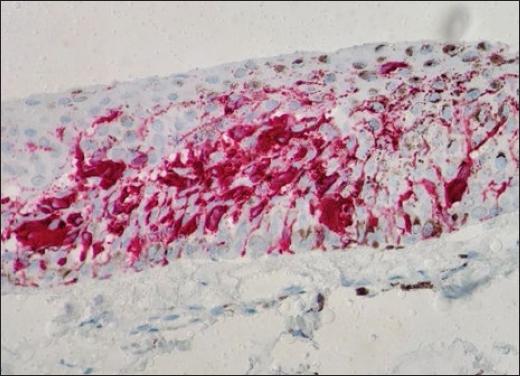

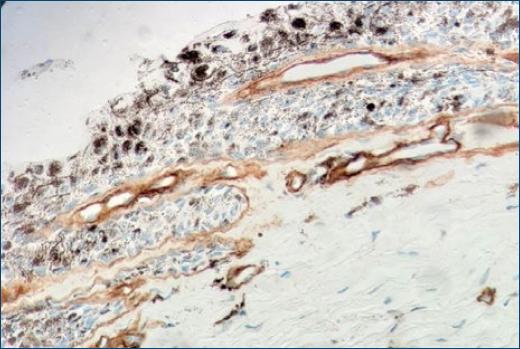

Dermatological examination showed an irregular, longitudinal brownish linear nail pigmentation, with a greater diameter near the proximal nail fold. On dermoscopy, the lesion had an irregular black to dark brown background, with breakage of parallelism, a positive Hutchinson’s micro sign and an enlarged base with distal narrowing (Fig. 1). Absence of palpable lymph nodes on physical examination. We opted for an excisional biopsy of the nail matrix, with 3 mm margins. The anatomopathological report was compatible with in situ acral lentiginous melanoma and immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for Melan A and Ki67 (90%). Collagen IV expression was intact in the basement membranes (Figs. 2–5). The patient was referred to the oncology clinic, where the nail apparatus was removed surgically while preserving the distal phalanx (Fig. 6). The patient remains under clinical follow-up with dermatology and oncology every six months and is free of lesions for two years.

Figure 1 On dermatoscopy: blackish-brown longitudinal lines, which are irregular both in color and thickness.

Figure 3 Immunohistochemistry with Collagen IV staining shows an intact basement membrane demarking neoplastic cells (400X).

Figure 4 Immunohistochemistry staining with MELAN-A showing atypical melanocytes scatted in epidermis (400X).

Discussion

Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), the most common clinical presentation of melanoma in African and Asian descent1-3, is a rare subtype in Caucasians with data in the literature ranging from 2 to 6%. ALM has an equal incidence in men and women and predominates in individuals between 50 and 70 years of age3,6,7. Any histological subtype of melanoma that occurs on the palms, soles, subungual or dorsum of hands and feet is considered acral melanoma3,8. The etiology is uncertain, but several factors such as trauma, chronic inflammation, and mechanical stress have been proposed3-5,8. As it is a pathology with few symptoms in the initial stages, added to the fact that it affects more advanced age groups and the inherent limitation for self-examination in acral regions, it is often detected in more advanced stages3. Clinically, there may be a pigmented longitudinal band (melanonychia), brownish to blackish, asymmetrical, with an irregular edge, and there may be dissemination of pigmentation to the proximal nail fold, giving rise to the Hutchinson sign, as in the present case. In more advanced stages, nail dystrophy, complete destruction of the nail plate and ulcerations may be present1,6,7. Genetic alterations may be involved in melanoma, with the mutation in the receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) being the most frequent in ALM (15–40%), whereas in other melanoma subtypes (superficial spreading melanoma and nodular melanoma) mutations occur more commonly in NRAS (17%), BRAF (50%) or PTEN3.

Other benign conditions can produce a sign similar to Hutchinson’s (pseudo-Hutchinson) such as Addison’s disease, HIV infection, Bowen’s disease, racial pigmentation (phototypes V and VI), and malnutrition, among others. Whereas the most common form of longitudinal melanonychia in adults is melanocytic activation, in children benign melanocytic nevus is the more frequent7,8.

Dermoscopy is an additional tool that can help distinguish between benign and malignant pigmentary lesions1,7. Suspicious lesions may present irregular longitudinal lines, with a diameter greater than 3 mm, abrupt interruption of parallelism in some areas, brown or black color and ill-defined borders.

Biopsy is indicated in suspicious lesions, namely those appearing after puberty, especially from the fourth to the sixth decade of life, any acquired lesion in patients with a personal history of melanoma and lesions with rapid and progressive growth6,9. Lesions smaller than 3 mm in diameter can be biopsied using 2 biopsy punches, one of 6 mm with removal of the pigmented nail plate and the other of 3–4 mm performed on the nail matrix. However, in lesions with a diameter between 3–6 mm and with pigment in the nail matrix, a transverse biopsy in the matrix is indicated, and removal in blocks with a “U” flap may be necessary if there is pigment in the proximal nail matrix9.

Histologically, confluent dendritic or epithelioid melanocytes can be identified, alone or in nests, at the dermoepidermal junction. Pagetoid migration may occur and dermal invasion takes the form of atypical epithelioid cords or nests3. Immunohistochemistry staining with markers such as MART-1, Melan-A, S-100, HMB45, and NKI/C3 complements the diagnosis, and a positive MART-1 or HMB45 and S100 protein with negative cytokeratin confirms the diagnosis of melanoma7.

Due to the proximity of the nail matrix to the underlying bone, wide excision with amputation of the phalanx is considered the first-line therapy in cases of melanoma of the nail unit, but additional therapies may be necessary depending on the extent of the lesion1,6. In in situ lesions, currently, more conservative surgeries are indicated, such as amputation of the distal phalanx, thus preserving the proximal phalanx1,3,7. In these lesions or others that are minimally invasive, some authors suggest wide local excision with removal of the nail plate, bed, and matrix, thus avoiding limb amputation6,8-10. In cases of locally advanced disease, the level of amputation of the phalanx will depend on the thickness and depth of the lesion9, while in metastatic disease the therapeutic options are chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted molecular therapy, and immunotherapy. Nevertheless, most agents used in targeted therapy are indicated for melanomas with mutations in BRAF, NRAS, and PTEN, whereas in the acral lentiginous subtype, the main mutation is in KIT, leaving few therapeutic options such as imatinib and sunitinib, both with variable clinical response1,3,7.

As ALM is an infrequent subtype and with a worse prognosis when compared to other subtypes, early diagnosis and an adequate therapeutic approach are essential for a better evolution of the condition, with greater chances of cure.