Introduction

Ashy dermatosis (AD) is a pigmentation dermatosis that belongs to the group of acquired macular hyperpigmentation disorders of uncertain etiology. It presents with blue-gray macules, symmetrically located on the trunk, neck and upper extremities1. Although the adulthood form is more common in higher Fitzpatrick skin types, pediatric cases are more common in Caucasian individuals with lower phototypes1. The authors report two cases of AD in pre-pubertal age and highlight the differences in epidemiology and course of the AD in children in comparison with adults.

Case report 1

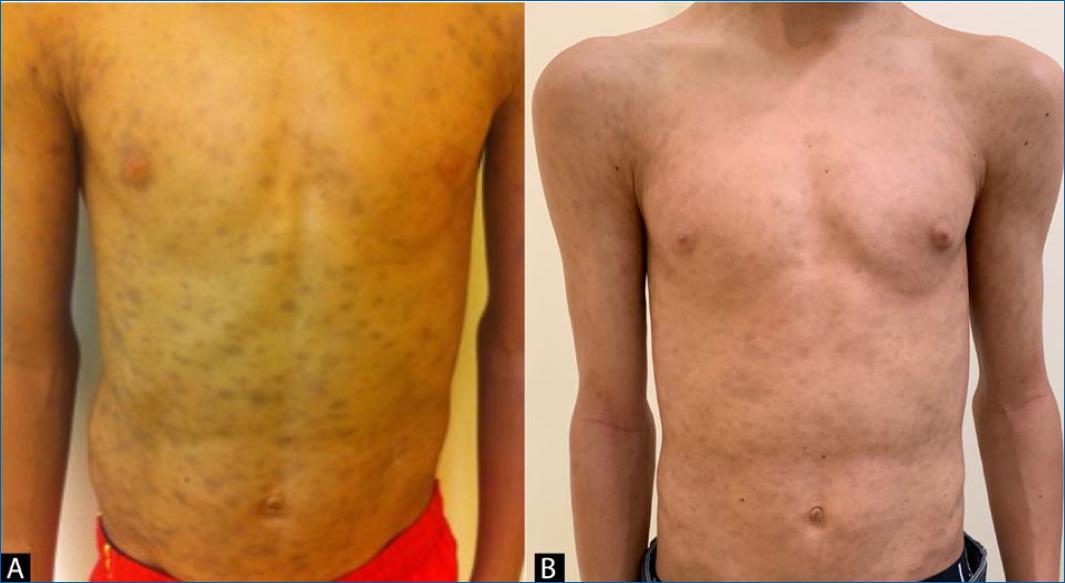

An 11-year-old boy, Fitzpatrick skin type III, presented with multiple blue to gray oval macules and patches between 5 and 15 mm, on his trunk, neck and proximal thighs (Fig. 1A). No erythematous border of the lesions was observed. The lesions had appeared suddenly one month before the dermatological observation and were asymptomatic. He was otherwise healthy and there was no previous intake of medication. His twin brother had no similar lesions. He was sent to the Dermatology Department with a diagnosis of multiple ecchymoses. His complete blood count and coagulation times were within the normal range. There was no history of trauma. A skin biopsy was performed and histopathology revealed focal vacuolar changes in basal stratum of the epidermis, a mild inflammatory perivascular infiltrate and dehiscence of pigment with interstitial and perivascular melanophages (Fig. 2).

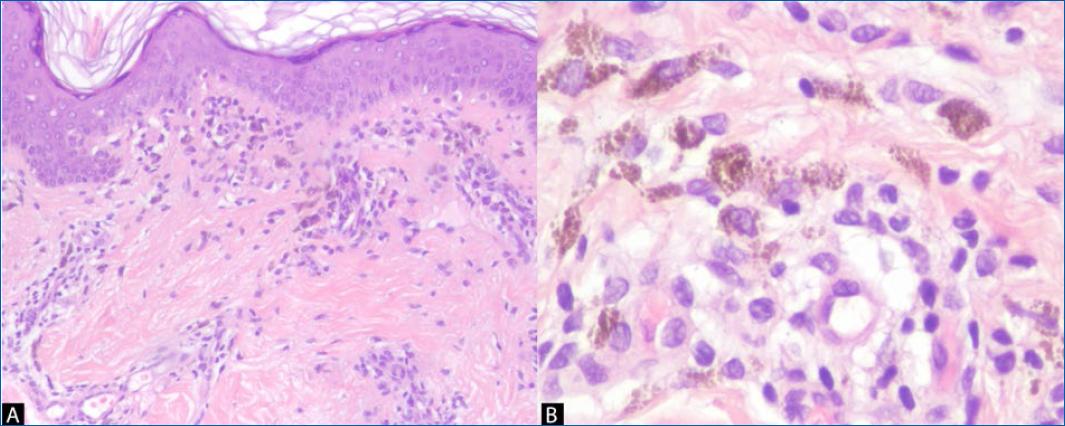

Figure 2 Histopathology of patient 1 with focal vacuolar changes in basal stratum of epidermis, mild inflammatory perivascular infiltrate, dehiscence of pigment with interstitial and perivascular melanophages (A: H&E, x100; B: H&E, x400).

A diagnosis of AD was made. The boy started treatment with a mometasone furoate 0.1% cream for 4 weeks, with no improvement of the dermatosis. At 3 years’ follow-up, lesions remain unchanged (Fig. 1B).

Case report 2

A 5-year-old girl, Fitzpatrick skin type II, presented with 5-20 mm, grayish oval macules on her trunk (Fig. 3A) with no erythematous rim. The lesions had had a gradual onset for 2 months. At the same time, the girl developed abdominal pain with diarrhea which led to the diagnosis of celiac disease. A biopsy of a cutaneous lesion revealed abundant perivascular macrophages with intracytoplasmic brownish pigment and no epidermal changes (Fig. 4).

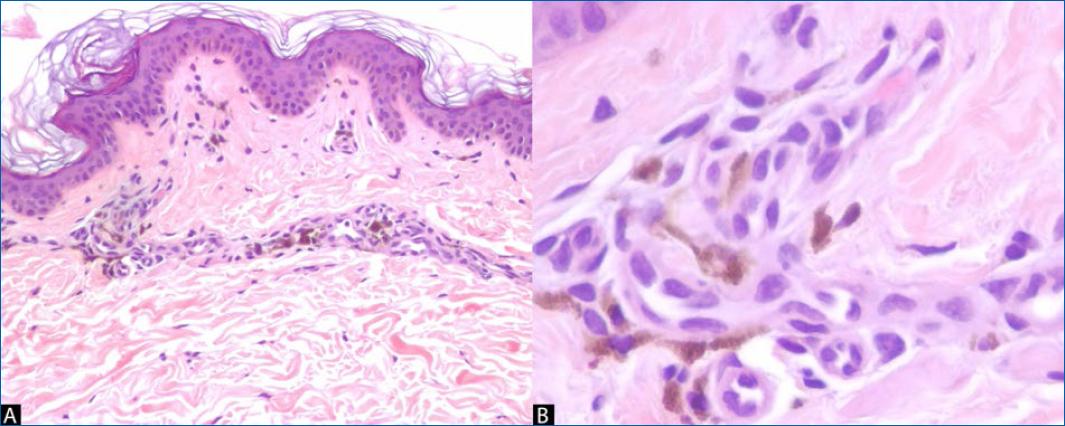

Figure 4 Histopathology of patient 2 with abundant perivascular macrophages with intracytoplasmic brownish pigment (A: H&E, x100; B: H&E, x400).

With a diagnosis of AD and celiac disease, the child started a gluten free diet with improvement of the gastrointestinal symptoms but no improvement of cutaneous lesions. No topical or systemic treatment was attempted. At 2 years’ follow-up, she maintains the same lesions (Fig. 3B).

Discussion

Ashy Dermatosis (AD) was first described in individuals from El Salvador in 19572. AD patients experience an onset of bluish or grayish macules, sometimes with an erythematous and elevated rim which eventually disappears within several months. Trunk, neck and upper limbs are the most commonly involved areas followed by face and lower limbs1,3. Palms and soles are usually unaffected4,5. Although it usually spares the mucous membranes, lesions on the oral cavity have been reported6. In most cases this is an asymptomatic condition but some patients may refer mild pruritus4.

Many authors consider AD and erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP) as the same disorder. However, a consensus published by a group of pigmentary disorders experts consider these as two separate entities, with the major difference between them being the presence of an erythematous border in the early active phase of EDP2. If there is no history or active presence of the erythematous border, it should be considered as AD1,2. Chang et al. reported that only 17.6% of 68 Korean patients with AD/EDP presented with the erythematous raised border3.

There are some interesting differences between childhood and adulthood cases. While most adult patients are Hispanic with higher phototypes, children affected are usually Caucasian and have lower phototypes4,7. Another difference is the spontaneous improvement or resolution in 50-69% of pre-pubertal patients, which contrasts with the persistent course in adults2,7. However, the evidence regarding pediatric patients is still limited, as few reports have addressed this dermatosis in children4,7.

Although there were some reports of AD following drugs and infections, the etiology mostly remains un- known2,3,7,8. In our patients, no clear trigger was identified except for the almost simultaneous onset of celiac disease on the second patient. However, we could not make a clear relation between these two entities as the gluten-free diet improved celiac disease manifestations but did not affect AD. A genetic contribution has also been proposed to contribute to the development of the AD2. However this could not be supported by our cases, since the first patient had a twin brother without lesions.

Primary histopathologic findings include pigment incontinence and melanophages in the dermis, along with mild to moderate superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltration. Usually there is basal vacuolar degeneration and a focal or lichenoid pattern with colloid bodies along the dermoepidermal junction 1,4.

Basal vacuolar degeneration and edematous papillary dermis with lymphocytic infiltrate indicate active lesions, whereas inactive lesions show melanophages and pigment incontinence in the dermis, with no inflammation3. This is in accordance with both our cases. In case 1, which presented to our department few weeks after the onset of the dermatosis, we found vacuolar alterations in the basal layer, with a mononuclear infiltrate, suggesting an active phase. In case 2, we did not find these aspects typical of the active phase, which is compatible with the longer duration of the dermatosis of the child before presenting to our consultation. However, the lack of the lichenoid aspects in case 2 makes it difficult to assume a definitive diagnosis of AD over idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP).

Other conditions may mimic AD/EDP, such as lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) and IEMP.

Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) most frequently affects sun-exposed areas, such as the face and neck, but can also affect flexural folds and rarely the oral mucosa1,9. While AD typically has a stable course, LPP is more likely to have a wax and waning history9. Histopathology alone cannot differentiate between AD/EDP and LPP10. Dermoscopy has been described as a useful tool when in doubt with LPP. In AD, dermoscopy shows gray-bluish small dots over a bluish background, whereas in LPP dots are brownish and larger than AD dots, and occur over a brownish background11.

Idiopathic eruptive macular pigmentation (IEMP) is an eruption of asymptomatic brownish macules, affecting the trunk, neck and proximal extremities, with no previous inflammatory lesions or drug exposure1. Lesions are typically smaller than the ones observed in AD2. IEMP affects both dark and light phototypes1. There is usually a hyperpigmentation of the basal layer of epidermis and prominent dermal melanophages, with no basal layer damage or lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate2,10. Lesions resolve without treatment in several months to years1.

There is no uniformly effective therapy for AD/EDP2, and most evidence regarding treatment results from case reports in adults. Although topical steroids are the most commonly used agents3,5, other options such as topical hydroquinone3,9, topical calcineurin inhibitors5,12 and topical tretinoin3,9 have been described with variable outcomes. Numata et al. reported the disappearance of the erythematous halo of the EDP lesions in an adult after the use of a topical steroid, but pigmented macules and patches persisted13. Multiple systemic drugs have been tried in the treatment of AD/EDP in adults, such as isotretinoin14,15, minocycline3, clofazimine16, dapsone5,17, and oral steroids9,15. There is also a report of resolution of AD after the administration of pembrolizumab in a 62-year-old patient with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung18. Phototherapy with narrow band UVB has been successful in the treatment of a 17-year-old male19.

In both cases reported in this article, no systemic treatment was attempted due to the benign course of the disease and lack of and lack of an effective and safe medication available. Spontaneous improvement or resolution of the lesions is seen in the majority of pre-pubertal children2,4. In a cohort of patients observed between 3 and 76 years, complete clearing was reported in 2%, improvement in 43.1%, worsening in 5.9%, and 49.0% showed no significant change3. Silverberg et al. reported complete clearance of AD in 5 of 8 pre-pubertal patients, with an average clearance time of 2.5 years and the longest duration of 5 years. The remaining three patients missed the follow-up7.

Conclusion

AD is a benign condition observed more common in Hispanic adult patients. However, considering the pre-pubertal age, it is more frequently observed in Caucasian children. Its insidious and persistent course may alarm the child’s caregivers. Therefore, it is important to explain them that although no efficient and safe therapy exists, most children will progress towards a spontaneous improvement or resolution.