Introduction

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular neoplasm caused by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) with a broad spectrum of clinicopathological manifestations1.

For the past decades, multiple histologic variants of KS have been reported, namely the lymphedematous subtypes, which include lymphangioma-like KS (LLKS), lymphangiectatic KS, and bullous KS2.

LLKS corresponds to < 5% of all reported KS cases and is mostly defined by the presence of ectatic vascular spaces with a labyrinthine architecture that dissects collagen bundles3.

We hereby present the case of a patient with lymphangioma-like classic KS, reviewing the clinical and pathological features of this rare entity.

Case report

An 80-year-old male, without relevant past medical history, presented to our department with erythematous to violaceous edematous plaques on the dorsum of both hands, especially on his right side (Fig. 1). These were soft and easily compressible lesions which had been slowly growing for 3 years and were now starting to limit his daily activities. On physical examination, no other mucocutaneous lesions were identified and lymph nodes were not palpable.

The patient denied any systemic symptoms, as well as prior malignancy or radiation therapy.

Routine laboratory workup, including complete blood count, was normal and serology testing for human immunodeficiency virus was negative. Additional investigation included a chest X-ray, an abdominal computed tomography scanning, and a fecal occult blood test, which were all negative.

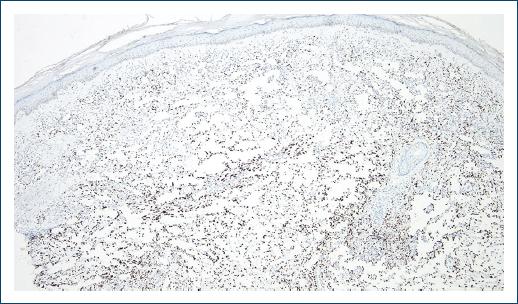

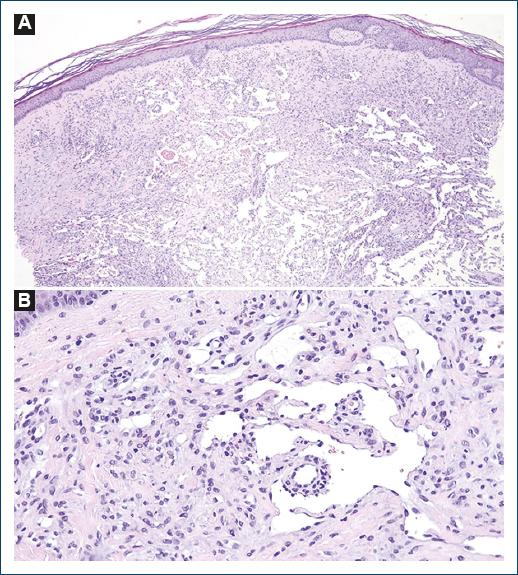

A skin punch biopsy was performed on the dorsum of the right hand and revealed an ill-defined vascular proliferation on the dermis admixed with an inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and rare plasma cells (Fig. 2A). The proliferation was composed of anastomosing angulated spaces lined by flattened endothelial cells, dissecting collagen bundles and surrounding pre-existing adnexal structures and blood vessels (Fig. 2B). No significant cytological atypia or mitoses was observed. There was no relevant hemosiderin deposition. Immunohistochemistry showed diffuse positive staining for HHV-8 (Fig. 3), as well as positive expression of CD31 and erythroblast transformation-specific-related gene (ERG) by endothelial cells.

Figure 2 A: vascular proliferation with numerous thin-walled ectatic vessels dissecting collagen bundles and anastomosing lymphangioma-like spaces (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], ×10); B: lymphangioma-like ectatic immature vessels lined by single-layered endothelial cells with isolation of one pre-existing vessel (H&E, ×100).

A diagnosis of lymphangioma-like Kaposi sarcoma (LLKS) was established. Therapeutic options were discussed but the patient declined any treatment, so a “wait-and-see” approach was adopted. At the last follow-up visit, his lesions remained stable.

Discussion

KS is a multifocal vascular neoplasm with four epidemiological subtypes recognized by the World Health Organization: classic or mediterranean, endemic or African, iatrogenic or post-transplant and epidemic or Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated4.

Mucocutaneous lesions of KS typically evolve from early macules (patch stage) into plaques (plaque stage) that may later grow into larger nodules (tumor stage)1. Extracutaneous locations, most commonly lymph nodes, lungs, or the gastrointestinal tract, may also be affected1.

Histologic features of KS vary with the stage of the lesion (patch, plaque, or nodule) but generally include ill-defined fascicles of spindle cells associated with slit-like vascular spaces that dissect the dermis and sometimes circulate around adnexal structures and pre-existing native vessels (“promontory” sign)5. A lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate, extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin deposits, and occasional hyaline globules are additional histologic clues1,5.

Over the years, numerous pathological KS variants have been described such as anaplastic, bullous, telangiectatic, keloidal, verrucous, micronodular, ecchymotic, pyogenic granuloma-like and the lymphedematous subtypes, which comprise lymphangiectatic, lymphangioma-like and bullous KS1,2.

Lymphangioma-like KS (LLKS) corresponds to < 5% of all reported KS cases and may virtually occur in all epidemiological settings6, although Ramirez et al. suggest a higher prevalence in patients with classic KS5.

Previous irradiation and chronic lymphedema have been hypothesized as risk factors for the development of LLKS, but their presence is not mandatory7,8.

Clinically, LLKS is characterized by the presence of tense vesiculobullous lesions with a serious content9,10. However, blisters are not always present and, in some cases, the clinical presentation may be indistinguishable from typical KS lesions6.

This entity affects mainly the extremities and is more frequent in males, usually above the sixth decade of life11,12, although a lower mean age at onset (45.1 years) has been reported in 20176.

On histology, LLKS stands out for its distinctive anastomosing networks of ectatic vessels in the dermis, which are lined by a layer of flat endothelial cells with no - or very mild - atypia3,5, resembling the dilated lymphatic channels of a lymphatic tumor, such as a benign lymphangioendothelioma/acquired progressive lymphangioma2. By contrast to classic KS, there is no prominent population of spindle cells13 and red blood cells, lymphocytes or thrombi are usually absent in those spaces5.

These findings are normally found in up to 50% of the lesional tissue, with adjacent typical KS histologic features that make the diagnosis easier5. On the other hand, when lymphangioma-like spaces occupy the entire lesion, differential diagnosis with other vascular tumors such as hemangiomas or hemangioendotheliomas may be challenging3. Immunohistochemical studies with positive staining for endothelial cell markers (CD31, CD34, and ERG), lymphatic markers (D2-40) and especially for HHV-8 may be key for confirming the diagnosis7,14.

The treatment of LLKS is similar to conventional KS, depending on the patient’s symptoms, immune status, the number of lesions, and the involvement of extracutaneous sites6.

Unlike other KS histologic variants2, LLKS seems to have prognostic significance, with a more indolent course than the traditional classic subtype6. This helped to further validate the “wait-and-see” option taken together with the patient in our case.

We believe this case is a good example of lymphangioma-like classic KS, presenting with the typical histologic features but some less common clinical findings as the absence of bullae.