Introduction

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is the most common autoimmune blistering disease, with prevalence of 0.13% in Europe and results from autoantibodies against hemidesmosomal proteins of the skin and mucous membranes1,2. Most antibodies belong to the immunoglobulin (Ig)G class and bind to the hemidesmosomal proteins BP180 and BP2303. Occurrence of BP in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has rarely been reported and it is possible to find autoantibodies of BP in HIV carrier blood, even without evident clinical manifestation1,4,5. Topical superpotent corticosteroids are the first-line treatment, along with doxycycline or oral prednisolone in extensive severe cases, usually with good response3. However, some severe and difficult cases may require alternative immunosuppressants for adequate clinical control. This work aims to report an exuberant case of BP in a patient with HIV virus infection, emphasizing the difficulty of treating this entity in this population.

Clinical case

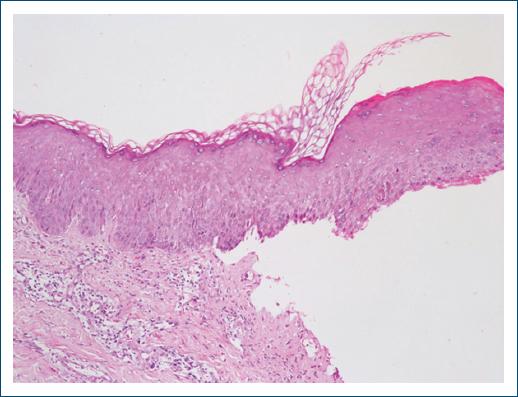

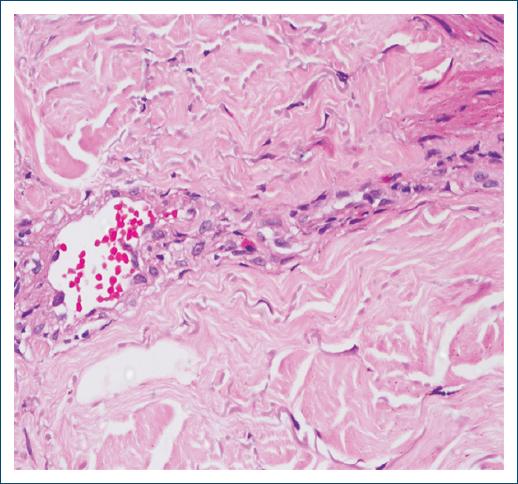

A 67-year-old Brazilian non-atopic man diagnosed with HIV infection for 6 years, in regular use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and undetectable viral load. He presented with disseminated pruritus and erythematous urticarial plaques with vesicles and tense bullae, initially on the trunk, upper, and lower limbs (Fig. 1), and subsequently on the face and mild involvement of the oral mucosa. Differential blood count showed mild eosinophilia and total IgE level was 623 kU/L (Ref. < 140 kU/L). BP was confirmed through histopathology, demonstrating acanthotic epidermis, subepidermal split, and perivascular dermal inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils (Figs. 2 and 3). Direct immunofluorescence revealed a linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the basement membrane zone, but no enzyme-linked immunoassay was performed to detect the level of anti-BP antibodies.

Figure 1 On admission day, the patient exhibited extensive erythematous plaques, some of which were smaller with an annular pattern and a rosy center. In addition, there were bloody crusts on the chest and abdomen.

The vesiculobullous eruption proved refractory to numerous therapeutic measures. Initially, we started oral prednisone at 2.0 mg/kg/day for 2 months, followed by a reduction to 1.0 mg/kg/day for an additional 2 months. Faced with a poor response, we administered methylprednisolone pulse therapy at 1 g/day intravenously for 5 days, maintaining oral prednisone at 1.0 mg/kg/day. In addition, oral doxycycline at 100 mg every 12 h and oral azathioprine at 100 mg/day were added for maintenance.

After 3 days post the completion of pulse therapy, new blisters continued to appear with persistent itching. Intravenous human immunoglobulin was then administered at 2.0 g/kg for 3 days, while continuing the existing medications. After 5 days, the patient once again developed pruritic blisters throughout the body, leading to plasmapheresis (a total of 5 sessions, with a 1-week interval between them). During this period, rituximab was provided, infused at 500 mg/week for 4 weeks, 1 week after the last plasma exchange session (Fig. 4). There was clinical remission after 6 months of rituximab, allowing for the tapering of oral corticosteroids, doxycycline, and azathioprine.

Figure 4 After the first cycle of rituximab, there is an absence of vesicles and blisters, with scattered crusts and no new lesions.

We conduct laboratory tests (complete blood count, liver function, renal function, fasting blood glucose, and urine analysis) every 48 h for infection screening and medication monitoring. Viral load and TCD4 cell count were assessed at admission and after 3 and 6 months, with no abnormal results at either time point. The patient remains under quarterly outpatient follow-up with the dermatology team and biannual follow-up with the infectious diseases team, showing no new lesions over the past 2 years.

Discussion

Since the onset of the HIV epidemic, a total of 34.5 million adults and 2.1 million children under the age of 15 were living with the virus in 20166. The introduction of HAART in 1995 has had a significant impact on the increased life expectancy of these patients. However, this progress also poses challenges, notably in the management of conditions associated with chronic HIV infection, namely autoimmune disorders.

The correlation between autoimmunity and HIV infection is complex and has not yet been fully understood. The depletion of CD4 T cells triggers an intensified activation of all immune system components7. Factors such as molecular mimicry to self-antigens, persistent antigenic stimulation, immune reconstitution under antiretroviral therapy (ART), and dysregulation in the interaction between T and B cells may justify this binomial1,7,8. The intricate web of physiopathological factors can pose a significant challenge in the treatment of autoimmune diseases in individuals with HIV, as illustrated in the current case.

T-helper 2 (TH2) immune response plays a central role in the pathogenesis of BP, as evidenced by the elevation of immunoglobulin E levels in 50% of patients9. During HIV infection, there is a decrease in the secretion of T-helper 1 (TH1) cytokines and an increase in the production of TH2 cytokines10,11. This observation suggests that the TH2-mediated immune response is a significant pathological mechanism in patients with HIV and BP1,4.

Successful ART neutralizes this shift in TH1/TH2 ratios and cytokine concentrations, but although there is evidence that TH2 cytokine levels decrease after the initiation of HAART, they persist at higher levels compared to HIV-negative controls12.

Rituximab is a human chimeric monoclonal antibody of IgG targeting CD20. When administered at therapeutic doses, it demonstrates the ability to induce rapid and complete depletion of B lymphocytes through various mechanisms. These include the induction of antibody-dependent complement-mediated cytotoxicity, leading to cell lysis, as well as the inhibition of cell growth progression and stimulation of cellular apoptosis13. The interaction of rituximab with CD20 results in the destruction of B lymphocytes, leading to a reduction in immunoglobulins and antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. These effects may culminate in symptom control and/or remission of immune-mediated diseases14.

In the literature, rituximab is frequently cited in the treatment of hematological neoplasms in HIV-infected individuals, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. In these cases, laboratory monitoring of viral load and CD4 T-cell count is conducted quarterly15,16.

It is worth noting that in NHL therapy, rituximab influences the interaction between HIV and B cells, promoting the depletion of these cells, accelerating the rate of CD4 T-cell depletion, and HIV replication in peripheral blood. In these patients, maintaining HAART during combined chemotherapy with rituximab can delay, although not entirely prevent, the decline in the count of these cells16.

Conclusion

The prevalence of autoimmune bullous disorders in HIV patients has risen with the advent of ART. This case report highlights that individuals with HIV infection can experience diseases mediated by organ-specific autoantibodies, encompassing severe and refractory manifestations of the condition. Further research into the intricate interplay between autoimmunity and HIV infection is crucial for advancing our understanding and enhancing the management of such conditions, particularly in refractory cases, as exemplified in this report.