Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) is characterized by the acute onset of vesiculobullous or scattered atypical target cutaneous lesions accompanied by severe involvement of multiple mucosal sites, predominantly oral, anogenital, and/or ocular mucosae1,2. It occurs concurrently with atypical pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae, predominantly in affected children and young adolescents1. Once classified within the spectrum of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrosis (SJS/TEN), multiple case reports and case series highlighted its distinct pathophysiological features, clinical characteristics, and evolution1-4. Compared with the SJS spectrum, MIRM typically has milder cutaneous involvement, with fewer detachments and discrete targetoid lesions, and presents with more severe mucous involvement1,2.

Case report 1

We present an otherwise healthy 1-year-old boy transferred to our emergency department due to suspected Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

This patient, after 48 hours of isolated fever, was diagnosed with acute otitis media and prescribed amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day. Later that day and still before starting the antibiotic, he developed mild rhinorrhoea, cough, and a mild facial rash, which then spread to the trunk.

On the 3rd day of illness, he was assessed in the emergency department for progression of the maculopapular rash to the trunk and a 5-cm plaque on his right posterior thigh. The patient was discharged on amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (7:1) 80 mg/kg/day every 8 hours and cetirizine 2.5 mg 12/12 h after the presumptive diagnosis of a viral rash.

The following day, the patient returned to the emergency department of the same hospital due to sustained fever, continued worsening of the mucocutaneous lesions, and refusal to eat. He was therefore transferred to our hospital.

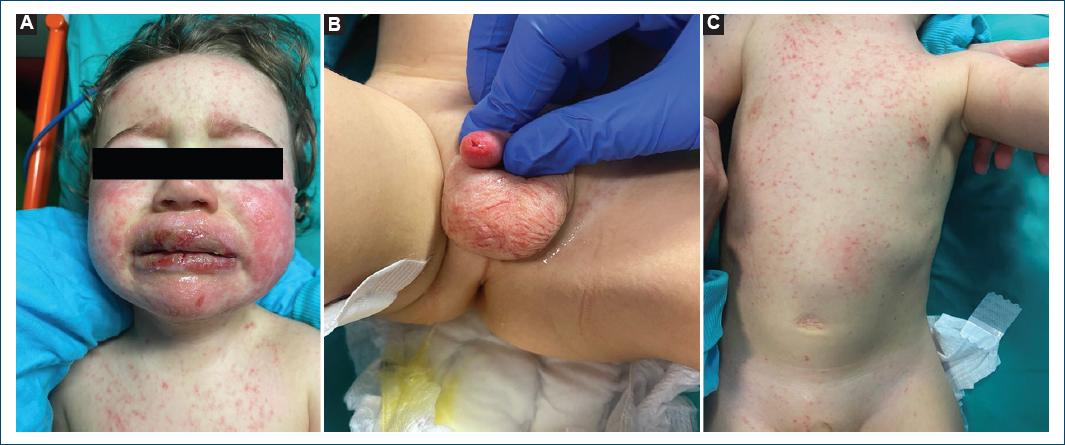

The clinical observation revealed gingival hyperemia and edema of the lips and oral mucosa, with painful erosions, some covered by hemorrhagic crusts, associated with bilateral tarsal hyperemia. In the malar regions and the chin, erythematous plaques with superimposed vesicles, bullae, and erosions were prominent (Fig. 1). He also presented erythema and edema of the glans penis and prepuce. The skin of the forehead, neck, and trunk revealed erythematous scattered papules without secondary features.

Figure 1 A: edema on the lips and erosions, some covered by hemorrhagic crusts. Erythematous plaques with superimposed vesicles, bullae, and erosions on the malar regions and chin. B: erythema and edema of the glans penis and prepuce. C: erythematous-purpuric macules scattered through the trunk.

Blood examinations revealed leukopenia (3.3 × 109/l) with neutropenia (1.32 × 109/l) and lymphopenia (1.87 × 109/l), elevated C- reactive protein (2.22 mg/dl), and procalcitonin (0.72 ng/ml). The PCR test for respiratory infections detected rhinovirus/enterovirus and M. pneumoniae, and serologies for EBV, CMV, and parvovirus yielded results without pathological significance. Hemoculture was negative. A chest radiograph showed bilateral interstitial infiltrates.

Therefore, we decided to suspend amoxicillinclavulanic acid and start intravenous hydration and clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day iv. every 12 hours and methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day. The patient was hospitalized for 7 days and presented a favorable clinical evolution, with pre-existing lesions already in the erosive-crusted phase, no new lesions, significant improvement in mucositis, and re-establishment of oral tolerance.

The patient was discharged with the plan to complete 10 days of clarithromycin, maintain a corticosteroid weaning schedule, and apply fusidic acid ointment on erosive areas of the face, lips, and limbs until healing and ocular antibiotic until symptomatic improvement.

Case report 2

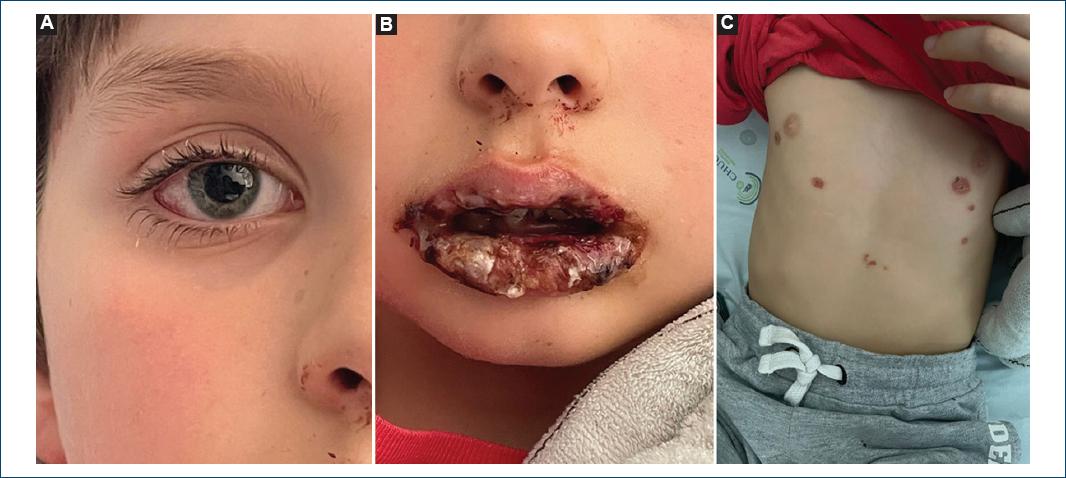

A previously healthy 8-year-old boy presented to our emergency department for a resurgence of fever (peak temperature: 39 °C), after 24 h of apyrexia, dry cough, and anorexia. Clinical examination showed a small number of grattage lesions in the trunk and a new onset of lower lip edema (Fig. 2). A chest radiograph showed no acute pleuroparenchymal changes. The blood count showed eosinophilia (1.40 × 10^9/l) and a mild elevation of C-reactive protein (1.32 mg/dl). The PCR test for respiratory infections detected M. pneumoniae. Four hours after the first observation, oral lesions worsened, with the development of multiple bullae and erosions and conjunctival hyperemia.

Figure 2 A: conjunctival hyperemia. B: edema and crusting lesions of the lips. C: vesicular lesions on the trunk that further progressed to crusts.

Therefore, we decided to start intravenous clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day every 12 hours. With no further aggravation, the patient was discharged the next day with the plan to complete 7 days of clarithromycin, maintain a corticosteroid weaning schedule (starting with methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day for 5 days and then 1 mg/kg/day to be slowly tapered for 1 month), and apply topical fusidic acid on affected skin and lip mucosa until healing and ocular antibiotic until symptomatic improvement.

He returned the day after discharge with worsening oral lesions and swelling of the lips and genital lesions, which led to refusal to eat and dysuria. On observation, he presented conjunctival hyperemia, profuse painful erosions in the oral mucosa, vesicular lesions and crusting on the trunk, and hyperemia of the glans penis and prepuce.

He was readmitted to our hospital where he stayed for 7 days and presented a favorable clinical outcome. During this period, he also developed involvement of the anal mucosa with pain during defecation.

At the time of discharge, lesions on the oral mucosa, trunk, and limbs progressed to crusting, lip edema persisted, but with good oral tolerance, and urinary symptoms resolved.

The patient was discharged with the plan to complete 10 days of clarithromycin, maintain corticosteroid 1 mg/kg/day until the next appointment, and apply fusidic acid on erosive areas of the face, lips, and limbs until healing and ocular antibiotic and corticosteroid until symptomatic improvement.

Discussion

M. pneumoniae is a bacterium that causes infectious tracheobronchitis and atypical pneumonia endemically and epidemically, affecting all age groups but most commonly school-aged children and adolescents5. Disease severity ranges from mild to life-threatening and organism resistance to empirical antibiotic therapy for community- acquired pneumonia (e.g., macrolides) is frequent and an emerging clinical challenge5. Extrapulmonary manifestations of the disease can be caused by the direct presence of bacteria and ensuing local inflammatory reaction or by an immune complex-mediated response; vascular occlusion plays an important pathological role in both mechanisms6. The most common of these manifestations involve the central nervous system, including early and late-onset forms of encephalitis, Guillain-Barré paralysis, transverse myelitis, and cranial nerve palsies and peripheral neuropathies5.

Cutaneous, cardiac, hematological, and renal involvement have also been described. Dermatological manifestations of M. pneumoniae infection are also among the most common and severe and include urticaria, anaphylactoid purpura, erythema nodosum, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, erythema multiforme major, and MIRM1,6.

MIRM is an acute mucocutaneous complication of M. pneumoniae infection caused by immune complex-mediated vascular injury, more frequent in male children. It includes vesiculobullous or scattered atypical target cutaneous lesions, papules, and/or macules, which are most frequently acral or generalized1,2. Multiple mucosal membranes can be involved, with oral, ocular, and/or urogenital mucosae being usually severely affected, whereas cutaneous involvement is usually mild to moderate and may even be absent1. Histopathological characteristics are unspecific and common to those of erythema multiforme, SJS, and TEN; apoptotic keratinocytes and a sparse perivascular dermal infiltrate are often described, but so far, no unique features of MIRM have been identified1,2.

Canavan et al. classified three different types of MIRM, proposing diagnostic criteria for typical MIRM, MIRM sine rash for isolated mucous disease, and severe MIRM.

These criteria firmly distinguish MIRM from the SJS/TEN spectrum, limiting diagnosis to patients with clinical and laboratory evidence (culture, antibodies, or PCR) of atypical pneumoniae caused by M. pneumoniae1. Our patient met these criteria, and, although a history of exposure to antibiotherapy placed SJS within our differential diagnosis, clinical presentation, age, and evolution are much more suggestive of MIRM.

Treatment of MIRM generally includes antibiotic therapy for pulmonary infection and immunosuppression (systemic corticotherapy or intravenous immunoglobulin) for mucocutaneous findings in severe cases. Extensive supportive care and a multidisciplinary approach to oral, urogenital, and ophthalmological manifestations are vital to prevent severe complications. Severe ocular disease is extremely destructive and can lead to symblepharon and permanent corneal blindness1,2. However, in most patients, diagnosis is favorable although recurrent disease has been described1,2.