INTRODUCTION

The use of immunotherapy in the treatment of solid organ and haematological malignancies has increased dramatically. Adoptive cell transfer methods and chimeric antigen receptor T‑cell (CAR‑T) therapies have both evolved as a result of a greater understanding of T‑cell pathways.1,2CAR‑T cells are biologically designed cells with a CAR receptor that identifies and binds to a particular protein: a tumor antigen.3-5

Despite the significant therapeutic potential of CAR‑T therapy for inducing remissions in refractory and relapsed malignant neoplasms,5,6high rates of treatment‑related toxicity have been reported, in contrast to those seen with conventional chemotherapies, monoclonal antibodies, and small‑molecule targeted therapies.3,4,7The toxic effects that are reported with CAR‑T cells are frequently on‑target effects. Their spectrum depends on the specificity of antibody single‑chain variable fragments and T‑cell activation. Thus, when the target cell is eliminated or the CAR‑T cell engraftment is terminated, these toxic effects are reversible. This reversibility stands in contrast to many of the toxic effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy, which can cause permanent genetic modifications of stem cells as well as other cells and are off‑target effects. These permanent changes may have clinically significant long‑term effects.3

Most observed toxicities are associated with cytokine release syndrome (CRS), characterized by high fever, hypotension, hypoxia, and/or multiorgan toxicity; and neurotoxicity, known as CAR‑T‑cell‑related encephalopathy syndrome (CRES). The latter, is typically characterized by a toxic encephalopathic state with symptoms of confusion, delirium, occasional seizures and cerebral edema.3,7,8Rare cases of fulminant haemophagocytic lymph histiocytosis (HLH), also known as macrophage‑activation syndrome (MAS), which is characterized by severe immune activation, lymphohistiocytic tissue infiltration, and immune mediated multiorgan failure, have also been reported.7-9Systemic toxicities associated with CAR‑T cells can potentially lead to acute kidney injury (AKI). The incidence of AKI reported in literature varies from 5% to 33%.2 Typically, the rise in serum creatinine is noted within 7 to 10 days after infusion and renal replacement therapy is rarely required.8 In previous studies using CAR‑T cells, electrolyte disorders were also reported.4,9The most common was hypokalaemia, followed by hypophosphatemia and finally, hyponatremia. It is unclear if this is directly related to CAR‑T cell therapy or a consequence of CRS.8

Given the increased interest in these therapies; it is important for nephrologists to understand their potential kidney effects. We present a series of adults with refractory and relapsed haematological malignancies treated with CAR‑T therapy. We aimed to characterize the AKI and electrolyte abnormalities that occurred in these patients, examining the relationship between these findings and clinical outcomes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective, observational study that included adult patients with refractory and relapsed haematological malignancies who received anti‑CD19 CAR‑T therapy between 2019 and July 2022 in Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto. Patients who were younger than 18 years old or were experiencing an unresolved episode of AKI at the initiation of CAR‑T infusion were excluded from the cohort. Patients were followed until August 2022 or time of death.

Study Approval Statement

The study protocol is according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Portuguese Oncology Institute of Porto.

Consent to Participate Statement

Given its retrospective and non‑interventional nature, we did not obtain patients’ informed consent.

Data Collection

All clinical data were elicited from the electronic clinical records and included demographic, comorbidities, and medication data at the time of CAR‑T therapy initiation. Laboratory data, including levels of serum creatinine, se‑ rum electrolytes, and lactate dehydrogenase were obtained within 7 days prior and first 30 days after CAR‑T administration. Post‑infusion treatment complications occurring in the first 30 days after CAR‑T administration were reported and included CRS, CRES, AKI and electrolyte disorders.

Baseline and post‑infusion glomerular filtration rate (GFR) were calculated by Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‑EPI) formula. Baseline chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for 90 or more days before CAR‑T therapy according to the kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines (KDIGO). AKI was defined as a 1.5‑fold increase in serum creatinine concentration from baseline value (on the 7 days prior to CAR‑T infusion) during the follow‑up period. Severity of AKI was graded according to the KDIGO. The resolution of an AKI episode was defined as a return of the serum creatinine concentration to within 25% of the baseline value. The grades of CRS and CRES were based on regular clinical assessments by the primary oncology team during the hospitalization and were graded according to American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT). Administration and doses of corticosteroids and tocilizumab for the management of systemic toxicities during the first month of follow‑up were also recorded.

Electrolyte disorders were defined using Common Termi‑ nology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as number (percent‑ age). Continuous variables were presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range). P values assessing patients demographics, clinical, and laboratory differences across AKI status were derived by Wilcoxon rank sum test for non‑normally distributed continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. The small sample size and low incidence of events limited our ability to perform an association analysis on the risk of AKI.

RESULTS

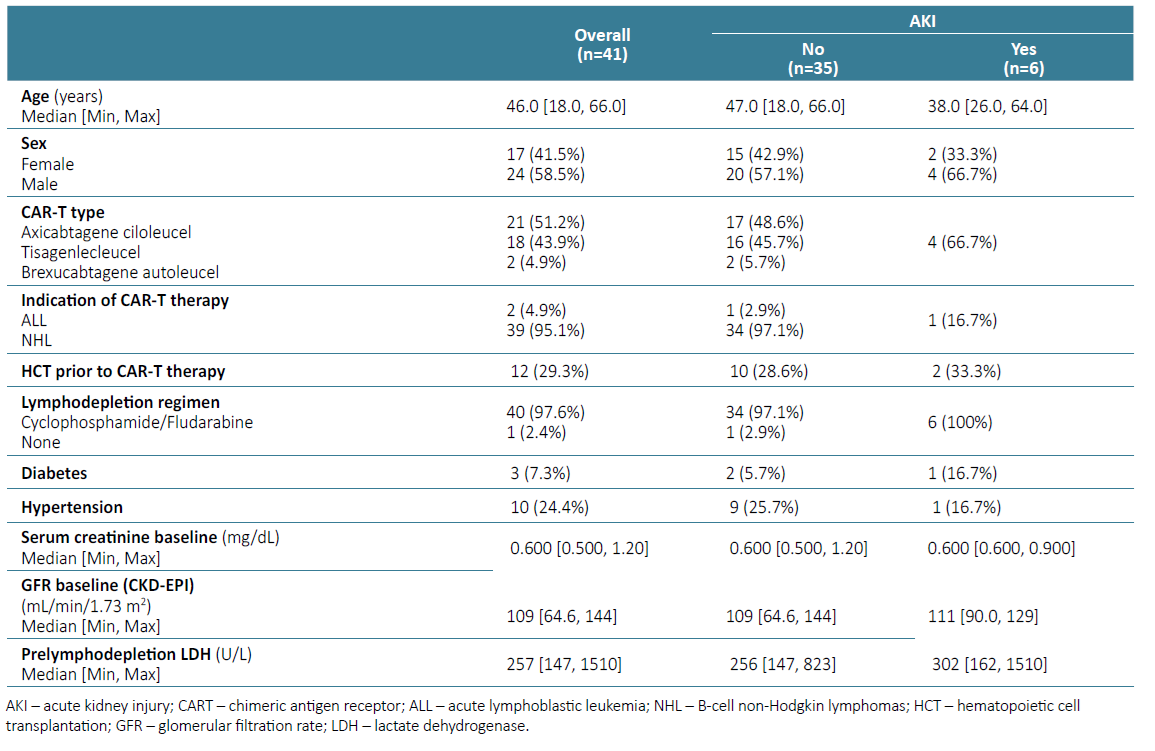

A total of 41 patients were treated during this period. Median follow‑up was 289 days (range 6‑994 days). Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1.

Median age of patients was 46 years (range 18‑66 years). The majority were male (58.5%). Most patients had B‑cell non‑Hodgkin lymphomas (95.1%) and received 2 lines of treatment and some of the patients underwent hematopoietic cell transplantation (29.3%) prior to CAR‑T cell therapy. Lymphodepletion regimen consisted in cyclophosphamide and fludarabine in nearly all patients (97.6%). Most patients received axicabtagene ciloleucel (51.2%), 43.9% received tisagenlecleucel and one patient received brexucabtagene autoleucel. Baseline comorbidities included hypertension (24.4%) and diabetes mellitus (7.3%). No patient had a history of heart disease, cirrhosis, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The median baseline creatinine prior to the start of lymphodepletion was 0.6 (range 0.5 - 1.2) mg/dL, and median GFR was 109 mL/ min/1.73 m2.

Post CAR‑T Cell Complications

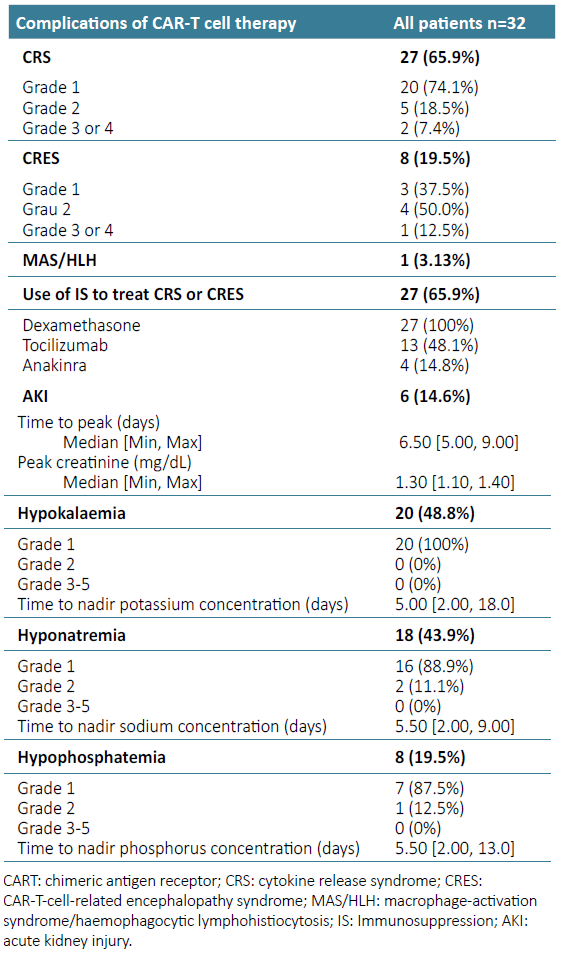

Post CAR‑T cell complications were recorded in 32 patients (Table 2).

CRS occurred in 27 (65.9%) patients and CRES was seen in 8 patients (19.5%). Six patients experienced both complications. MAS/HLN was noticed in 1 patient. Six patients developed an incident AKI event (14.6%) and 27 had electrolyte abnormalities (65.9%).

Four patients (66.7%) had stage 1 AKI and 2 patients had stage 2 AKI. Median time of AKI after initiation of CAR‑T therapy was 6.5 days (range 5.0 to 9.0). There was no administration of nephrotoxins at the time of kidney injury, and obstruction the urinary tract was excluded in all cases of AKI. Median uric acid level of patients with AKI was 3.7 (range 2.5‑5) mg/dL. No patient had substantial elevations in uric acid levels after CAR‑T therapy. All AKI episodes reversed with improved fluid intake or intravenous fluid support.

Grade 1 hypokalaemia was the most prevalent abnormality, observed in 20 patients (48.8%). Hyponatremia occurred in 18 patients (43.9%), with 2 patients experiencing grade 2 hyponatremia. Eight patients (19.5%) developed hypophosphatemia: grade 1 in 7 patients and grade 2 in a single patient. No patient experienced grade 2 or higher hypokalaemia, nor did any have had grade 3‑5 hyponatremia or hypophosphatemia. Median time to nadir for electrolyte abnormalities was 5 to 6 days from time of CAR‑T administration.

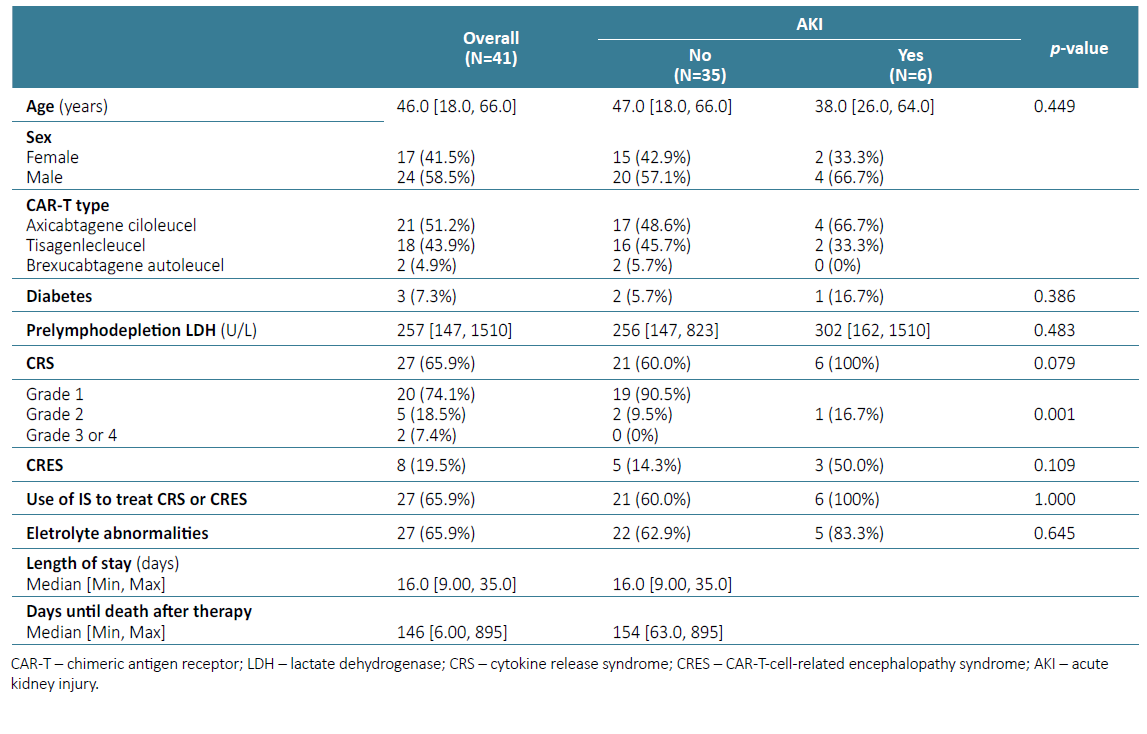

There were significant differences between AKI group and no‑AKI group in relation to grade CRS, with larger percentage of grade 2 CRS or higher in the AKI group (p=0.001) (Table 3). Although most patients with AKI received axicabtagene ciloleucel (66.7%), there were no significant differences in CART construct administered between groups.

Length of Stay and Mortality During the Follow‑up Period

During the follow‑up, we registered 12 deaths: 1 from complication of therapy (grade 4 CRES), 1 from infectious complication unrelated with therapy (occurred 159 days after therapy) and 10 associated to progression of the underlying cancer.

As shown in Table 3, among patients with AKI, median length of stay was 20 days and days until death after therapy were 9.5. These results were significantly different from patients who did not have AKI (p=0.04).

Of the 4 patients who survived during admission for CAR‑T, all returned to creatinine level and GFR baselines. At end follow‑up, the patients had median creatinine of 0.7 (range 0.6 - 0.8) mg/dL, and median GFR of 106 [(range 106-122.4) mL/min/1.73 m2].

DISCUSSION

CAR‑T therapy has been a breakthrough in anticancer therapy. However, it also has an unique toxicity profile and is increasingly becoming recognized as a cause of renal adverse events.

The mechanism of AKI in patients with CAR‑T cell therapy is not completely understood. However, it is proposed that the release of high concentrations of cytokines can lead to vasodilation, decreased cardiac output, and intravascular volume depletion due to increased vascular permeability and third spacing of fluids, causing reduced kidney perfusion, and potentially leading to acute tubular injury. In addition, high fever and nausea/vomiting associated with CRS induce intravascular volume depletion and/or CRS-related cardiomyopathy can also lead to a shock state and acute cardiorenal syndrome with concomitant AKI. Cytokines themselves may potentiate the renal injury due to intrarenal inflammation. Accumulation of fluid in the interstitial space leads to other problems, such as pleural effusions, peripheral, pulmonary and intestinal oedema, ascites, and muscle oedema. Rarely, AKI can result from severe ascites or rhabdomyolysis secondary to compartment syndrome and/or muscle oedema. In patients with large tumour burdens treated with CAR‑T cells, tumour lysis syndrome constitutes another potential mechanism for AKI.8,9

We found a low rate of AKI and most patients experienced only mild AKI and all (except those who died during hospitalization) recovered renal function. Our reported incidence of AKI was lower than the 30% found in the study by Gurtgarts et al10; however, it was comparable to results published in previous studies.2,11,12AKI occurred within 5 to 10 days after CAR T therapy, coinciding with CRS, and based on clinical data, appeared to be secondary to decreased kidney perfusion. In a systematic review, Kanduri et al2 found that higher grades of CRS were significantly associated with AKI after CAR‑T infusion. Despite the small sample of our study, we found significant differences between the group with and without AKI regarding CRS grade, with a larger percentage of grade 2 or higher CRS in the AKI group. Our findings suggest possible association between AKI and CRS severity, though this needs to be validated in a larger study. Our centre’s protocol includes close monitoring of serum biomarkers, fluid support, and early initiation of corticosteroids or tocilizumab during episodes of CRS; these attitudes may have contributed to reduce the incidence of severe CRS and consequently of AKI in this series.

The structure of the chimeric antigen receptor may contribute to patterns of toxicity. Most patients (51.2%) described in this series received axicabtagene ciloleucel, a CD19‑targeting CAR ‑T that has a CD28 costimulatory domain and is characterized by rapid T‑cell expansion and robust inflammatory cytokine secretion. The remaining patients received tisagenlecleucel CAR construct, which targets the same epitope of CD19 but has a different costimulatory domain (4 ‑1BB) and is associated with a reduced inflammatory profile.13 Although not statistically significant, it should be noted that most patients with AKI received axicabtagene ciloleucel. In the group without AKI the percentage of patients who received axicabtagene ciloleucel and tisagenlecleucel was similar.

We also found that electrolyte abnormalities were common among recipients of CAR‑T, but rates of clinically relevant hypokalaemia, hyponatremia and hypophosphatemia were low. This may be due to lower rates and grade of CRS and/or close monitoring and management of electrolyte disturbances, according to protocols established in our institution.

Moreover, our findings indicated that patients who developed AKI experienced higher mortality rates within a shorter timeframe and longer hospitalization durations. Various studies have consistently demonstrated that AKI occurrence during a hospital stay is associated with a higher likelihood of mortality compared to patients without AKI, leading to increased healthcare resource utilization and potentially higher healthcare costs.14,15The severity and duration of AKI episodes often correlate with the increased risk of adverse outcomes, making it an important factor to consider in patient care and management strategies.

Our study is limited by the relatively small cohort size, as well as its observational and retrospective nature, which precludes further hazard risk analysis to identify other modifiable risk factors. As experience with CAR‑T cells grows, larger studies are needed to stratify patients according to their risk of toxicity, including kidney injury.

Despite its limitations, this study is first to describe the experience of a Portuguese Center with CAR ‑T therapy and its effects on renal function and electrolyte disorders. The utility of CAR‑T therapies has significantly expanded across various cancer types. Collaboration between nephrologists and cancer specialists is essential to comprehend these innovative treatments and their renal implications. Careful administration of resuscitative crystalloid fluids can stabilize and reverse AKI in patients with mild cytokine release syndrome, while more severe cases might require loop diuretics and dialysis. Recognizing the significance of CAR‑T cell therapy and its renal effects is crucial for nephrologists treating cancer patients.

In conclusion, this study observed a low incidence of AKI, mostly resolving by the end of follow‑up, and although electrolyte abnormalities were common, they tended to be mild.