INTRODUCTION

In the 21st century, chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become a leading cause of mortality and suffering. CKD is a progressive disease that affects >10% of the population globally, totaling >800 million people and this number is rising.1 In Portugal, the prevalence of CKD was estimated at 20.9%, higher than the world and European average. According to the Portuguese Register of Renal Replacement Therapy in 2022, 21 327 patients were treated by dialysis or with a functioning kidney transplant.2,3End‑stage renal disease requiring dialysis is a significant condition with a high disease burden, morbidity, and mortality rate. For those over 75 years, the mortality rate during the first year of dialysis is close to 40%, and even those with a better prognosis are more prone to frequent hospitalizations and deterioration in functional status. Compared with patients with cancer or heart failure, dialysis patients have higher rates of hospitalization, intensive care unit stay, procedures, and hospital mortality. This high level of care is often against the interests of dialysis patients, but it continues because the patient’s goals, values and preferences are not explored or discussed in the context of their critical illness. Less than 10% of dialysis patients say they have discussed their goals, values and preferences with their nephrologist, even though over 90% say they want to. Many nephrologists avoid having these discussions with their patients because they do not want to upset them, believe it is too difficult to predict prognoses, are unsure of their ability to do so, are uncomfortable bringing up the subject, or find it challenging to integrate the discussions into their daily clinical practice. However, timely conversations about serious illness care goals have been linked to better care that is compatible with objectives, better quality of life, and favorable family outcomes without raising patient distress or worry.4‑6

COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION

Communication is defined as an exchange of information, a dynamic and bidirectional process that requires reciprocity and exchange of meanings between a sender and a receiver. Verbal communication constitutes 25% of our overall communication, but the majority (75%) is non‑verbal and is related to facial expression, posture, body movements, eye contact, hand movements and voice quality.7,8

Information is defined by content that expresses facts, ideals and feelings and that makes someone aware of something. It is unidirectional, does not require reciprocity and does not establish a relationship, it just expresses something.7,8

Effective communication implies, in addition to sharing information, other factors such as non‑verbal communication, listening, clarification, argumentation, persuasion, negotiation, reinforcement and reflection. It plays an important role in facilitating adaptation to the reality of living with a serious illness. Effective communication between patient and medical team is essential. Basic communication skills are needed to achieve good results in patient‑centered care, to understand what is important to the patient and to increase their participation in their own care.9

THE RATIONALE FOR THE NEED TO ACQUIRE COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN NEPHROLOGY

In Nephrology, effective communication between patient and nephrologist is crucial. Chronic kidney disease (CKD), being a chronic disease demands a variety of information that is needed to manage comorbidities, to adhere to complex drug regimens, or to adhere to vital activities and self‑care (such as weight loss, dietary adjustments, home blood pressure monitoring). Ineffective communication can lead to inadequate information, insufficient preparation for kidney replacement therapies (dialysis or kidney transplantation), lower adherence to self‑care and worse health outcomes. There is a need to improve communication between patients and nephrologists: patients want more knowledge about the disease process, self‑care practices, available treatments, and the psychosocial effects of end‑stage renal disease (ESKD).9,10

Selman et al, provide a detailed description of the communication experience between patients with chronic kidney disease and the nephrologist. Participants reported variable quality of medical team‑patient communication and gaps in information provided. Participants described that nephrologists avoided, struggled with, or did not talk to them about the diagnosis and progression of the disease. As a result of this lack of communication, patients were unable to modify their diet/health behavior at the onset of the disease, not knowing what symptoms or is‑ sues were attributable to their kidney disease and were concerned about what would happen in the future. This lack of knowledge compounded the challenges of living with the uncertainty of CKD.11

An Australian study identified the communicative practices of nephrologists during discussions with patients with chronic kidney disease addressing decisions about renal replacement therapy and determined how these practices impact shared decision making. It showed a variety of challenges that doctors faced in getting some patients to make decisions, given the complexities of clinical, cultural, linguistic and lack of time in the consultation. The study revealed that there is an urgent need for nephrologists to train and acquire skills in effective communication for effective and informed shared decision‑making, ensuring an explicit discussion of all clinically relevant factors regarding renal replacement therapy options.12

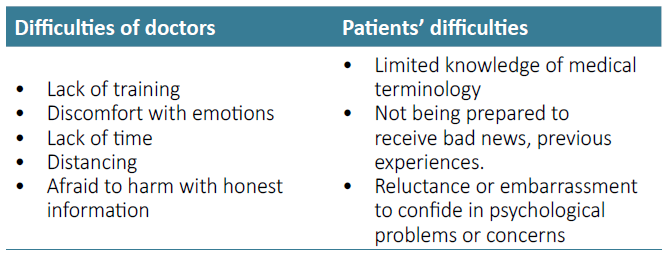

BARRIERS TO THE COMMUNICATION PROCESS

Several barriers need to be overcome to allow effective communication between nephrologists and patients (Table 1).4,9

The Disease and Prognosis are Understood by the Patient

Patients can benefit from discussing their goals and preferred treatments when they are aware of their diagnosis and prognosis. It is estimated that despite the fact that patients want to know the course and prognosis of their disease, nephrologists are often unwilling to address it, failing to offer any prognostic estimate for up to 60% of patients. When clinicians discuss prognosis, they often err on the side of overconfidence, which can impede patients’ ability to make wise decisions and provide treatment consistent with their goals. 4,9,13

Patient Emotions

The patient’s emotions can limit communication and understanding. Anxiety is a common symptom among individuals with chronic illnesses such as CKD. Two significant patient‑related factors-anxiety and denial-regularly make it difficult to articulate treatment goals for serious illness.9,14

Patient Expectations

More often than not, patients expect their physicians to initiate the conversation about advance care planning and end‑of‑life wishes. In this context, physicians’ hesitation to address these issues can lead them to make treatment decisions without having sufficient knowledge of their patient’s preferences.9,15

Under‑Trained Clinicians

For a variety of reasons, many nephrologists avoid having difficult conversations with patients about serious illnesses: they find it difficult to take the time; they do not see it as their responsibility or as an essential component of their clinical role; they do not want to upset the patients; they believe there is too much uncertainty in their ability to predict prognosis; and/or they are uneasy about how to approach the issue. Few nephrology residents report having received training in communication skills during their residency, despite the fact that many of them express a desire to improve their communication skills about critical illness. As a result, few nephrologists have the expertise to conduct conversations about serious illnesses such as CKD. Thismakes them uncomfortable to address end‑of‑life issues and inadequately prepared to respond to the strong emotions that conversations about serious illnesses arouse, which may contribute to preventing this topic.4

Schell et al, report the value of having a communication skills course for nephrology fellows (NephroTalk) that focuses on conveying bad news and helping patients in defining care goals, including end‑of‑life desires. All responders said they would suggest the program to other fellows. NephroTalk is effective in preparing nephrology fellows for challenging conversations about dialysis decision‑making and end‑of‑life care and its implementation in the Nephrology training program should be considered.16

Timing and Time

Finding the appropriate time for dialogue from the perspective of the patient during the course of the illness is difficult. Before the patient begins dialysis, a discussion regarding the prognosis of chronic renal disease should take place. Patients might still gain from serious illness discussions after starting dialysis to explore their objectives and preferences as their disease and dialysis experience change. The practical difficulties of scheduling such a conversation with dialysis patients are significant. In the dialysis unit, treatment takes up most of the time. While the patient is receiving dialysis does not provide the privacy that patients frequently want for such a sensitive topic. The availability of family members or caretakers may also be restricted by time constraints.4,9

End‑of‑Life Communication Training

Few trainees report having appropriate training in communication about end‑of‑life issues, despite the fact that nephrologists regularly need to interact with patients about end‑of‑life care and strongly wish greater learning about end‑of‑life communication. For instance, 73% of nephrology fellows say they were not trained how to tell when a patient was dying, and 72% of them say they were not prepared to manage the end‑of‑life care of a patient who stopped receiving dialysis.9,17

HEALTH COMMUNICATION MODELS

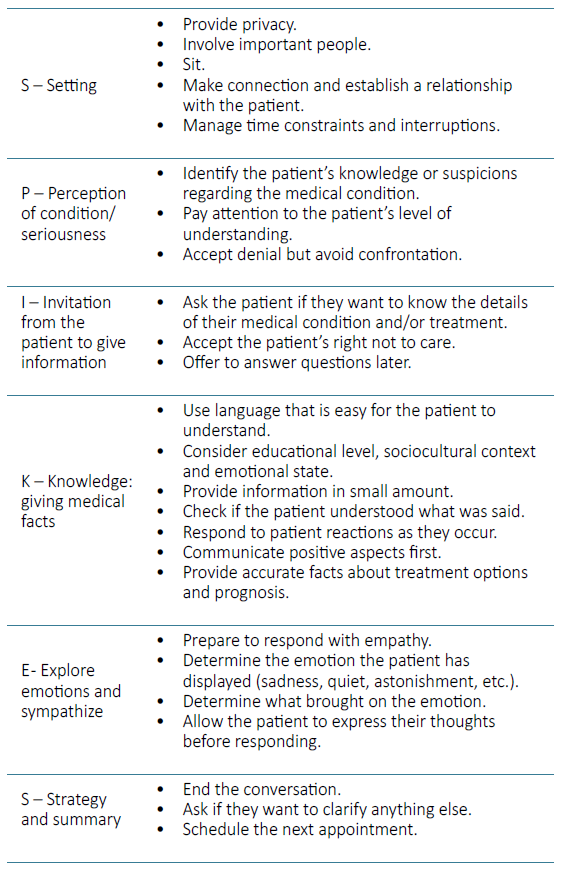

One of the most popular and accepted strategies for communicating bad news around the world is the SPIKES protocol (Setting up, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategy and Summary), which was published in 2000 by Walter F. Baile. This protocol, which is widely used in cancer patients, is also used in patients with CKD, especially those with terminal CKD. The four goals of the SPIKES protocol for communicating bad news are as follows:

Collecting patient information.

Providing medical data.

Giving patient support.

Seeking the patient’s participation in the development of a plan or course of action for the future.

The six steps of SPIKES protocol are described in Table 2.18‑21

REMAP (Reframe, Expect, Map, Align, Plan) was published by the Journal of Oncology Practice in 2017. It provides a step‑by‑step approach to complex goals of care conversations. With REMAP, the clinician can determine a patient’s primary values, goals, and fears, which will help the clinician develop a plan that honors those values, goals, and fears. The processes underlying REMAP encourage clinicians to seek to understand and remain flexible, adapting their recommendations to what they hear from the patient, with ongoing review based on a shared decision‑making process. This will lead to patient‑centric decisions that will promote better end‑of‑life care.

1.MAP (Map out what´s important)

Understand the patient’s goals in order to adjust the care plan: some people want to live as long as possible and choose treatments that allow them to do so, even at the expense of being hospitalized several times; Other people value quality of life; What is important for the patient?;

Explore hopes and expectations: What do you think about the future and what do you want to achieve; What makes your life worthwhile? What do you hope to achieve with dialysis treatment?;

Explore concerns: What are your biggest fears and concerns about your health in the future;

Explore boundaries: What skills are so important to you that you cannot see yourself living without them? Under what circumstances would you feel your life was not worth living?

2. ALIGN and PLAN

Propose and agree on a medical plan in accordance with the patient’s goals and values, namely considering crisis situations that can be foreseen and planning the care to be received;

Document/record decisions so that they are known by the health professionals in charge of the patient;

Review the agreement if health conditions and need for care change.

CONCLUSION

Nephrologists care for a clinically complex population that faces difficult decisions about treatment options and end‑of‑life care.19

Good patient‑centered communication is associated with better adherence to treatment, pain control, satisfaction, emotional health, functional status, confidence, and physical outcomes. If not communicated in the right way, it can result in impaired emotional response in patients, as well as excessive stress, negative attitudes towards the treatment team, and unsatisfactory outcomes.19,21

Appropriate decision‑making, quality of life and adaptation to the realities of the disease are significantly aided by effective communication. However, communication training within the nephrology fellowship is rare. We must routinely incorporate communication about treatment goals into our clinical care structures and processes. 19