INTRODUCTION

Portugal has one of the uppermost incidences and the highest prevalence of end‑stage kidney disease in Europe, according to United States Renal Data System report and the ERA‑EDTA latest annual report.1,2This trend is not yet fully understood, although several explanations are pointed out in the literature: a) a higher prevalence of multiple chronic kidney disease (CKD) risk factors, namely hypertension, diabetes mellitus and high salt intake; b) genetic predisposition; c) low health literacy and late referral to nephrology appointments; d) easy availability of haemodialysis (HD) throughout the country; and e) the heterogeneity and subjectivity of kidney replacement therapy criteria, as well as, the lack of clear guidelines for conservative therapy.3

Dialysis is the most common modality of renal replacement therapy globally, with HD being the predominant method.4 This tendency is also seen in Portugal.5,6In 2021, Almeida et al reported 16775 incident cases of HD in Portugal between 2010 and 2016 with incidences ranging from 229 per million population to 250 per million population according to the analyzed year.3 Furthermore, they found the Lisbon and Tagus Valley region had the highest incidence of HD in the country in the given period.3

Despite the fact that 91.8% of HD patients are treated in satellite dialysis centers and only 8.2% in the hospital setting (data from 2021), in order to be referred for HD in these centers, patients are first evaluated in nephrology departments of public hospitals.3,6

Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Norte (CHULN) is a public tertiary care university hospital in Lisbon, Portugal, and the largest hospital in the country. It serves around 329 000 individuals from its area of influence, and patients referred from other hospitals and evacuated patients from African Countries of whom Portuguese is the Official Language (PALOP).7

The aim of our study was to analyze a cohort of patients who started HD in CHULN as well as, describing the evolution of the patient characteristics throughout the studied years.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was a retrospective analysis of individuals who started HD between January of 2014 and December of 2019 in CHULN. The Ethical Committee authorized this study in accordance to institutional guidelines. Informed consent was waived, given the retrospective and non‑interventional nature of the study.

Participants

All adult patients (≥18 years of age) with CKD who started HD from January 1st of 2016 to December 31st of 2019 were considered eligible. We included both urgent and planned renal replacement therapy (RRT) start.

Variables

Data was attained from individual electronic clinical records. The following variables were gathered: demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethinicity); viral status [hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)]; CKD etiology (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, glomerular disease, inherited kidney disease, interstitial nephritis, obstructive nephropathy, unknown); comorbidities [active malignancy, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, chronic hepatic disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, ischemic cardiopathy, peripheral artery disease]; HD access at dialysis start (central venous catheter, arteriovenous fistula, arteriovenous graft); transition from other RRT modalities (peritoneal dialysis, kidney transplantation); estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at HD start. The primary outcome was mortality. We also assessed follow‑up time and mortality within the first 90 days of starting HD.

Definitions

The eGFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD‑EPI) creatinine equation.8

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, dementia and chronic liver disease were assumed based on previously known clinical diagnosis. Ischemic cardiomyopathy included chronic coronary artery disease and previous myocardial infarction. COPD included emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Cerebrovascular disease was considered based upon prior history of stroke, carotid, intracranial or vertebral stenosis, aneurysms or vascular malformations.

Statistical Methods

Categorical variables were described as the total number and percentage of each category, while continuous variables were described as the mean ± standard deviation. The Kolmogorov‑Smirnov normality test was used to ex‑ amine if variables were normally distributed. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t‑test, whereas categorical variables were compared using Chi‑square test.

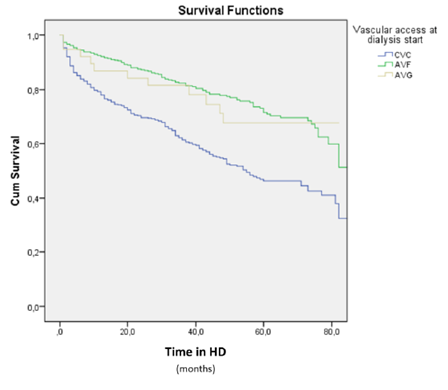

Kaplan‑Meier survival analysis were used to compute the survival over time and its differences according to age and vascular access at HD start during the given follow‑up. Statistical significance was defined as a p‑value lower than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the statis‑ tical software package SPSS for Windows (version 21.0).

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Characteristics

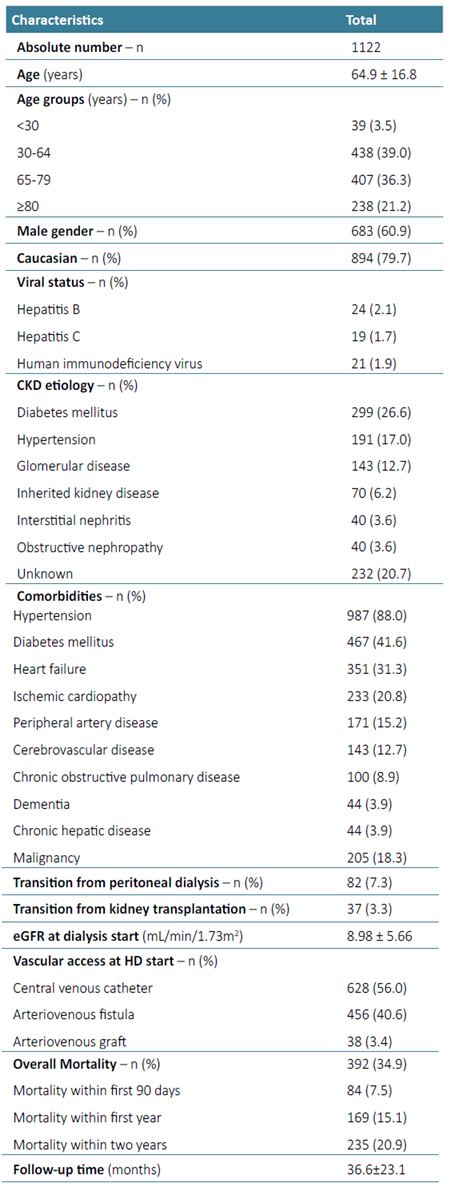

A total of 1122 patients who started HD in the chosen period were included. The baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean age of the population was 64.9 ±16.8 years with 21.2% of patients being at least 80 years old. Sixty percent were male and 79.7% caucasian. The most common CKD etiology was diabetes mellitus (26.6%) followed by unknown causes (20.7%) and hyper‑ tension (17.0%). There was a large prevalence of hypertension (88.0%), diabetes mellitus (41.6%), heart failure (31.3%) and ischemic cardiopathy (20.8%). Concerning viral serologies, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV were present in 2.1%, 1.7% and 1.9% of patients, respectively. At HD start, mean eGFR was 8.98 ±5.66 mL/min/1.73 m2. Eighty‑two (7.3%) patients transitioned to HD from peritoneal dialysis and thirty‑seven (3.3%) had a previous kidney transplantation. Regarding vascular access at HD start, 56.0% had a central venous catheter, 40.6% an arteriovenous fistula and 3.4% a arteriovenous graft. Mean follow‑up was 36.6 ±23.1 months. During this follow‑up, 392 patients (34.9%) died. Mortality within the first 90 days of starting HD was registered in 7.5% of patients (n=84).

Patient Characteristics Evolution Over the Years

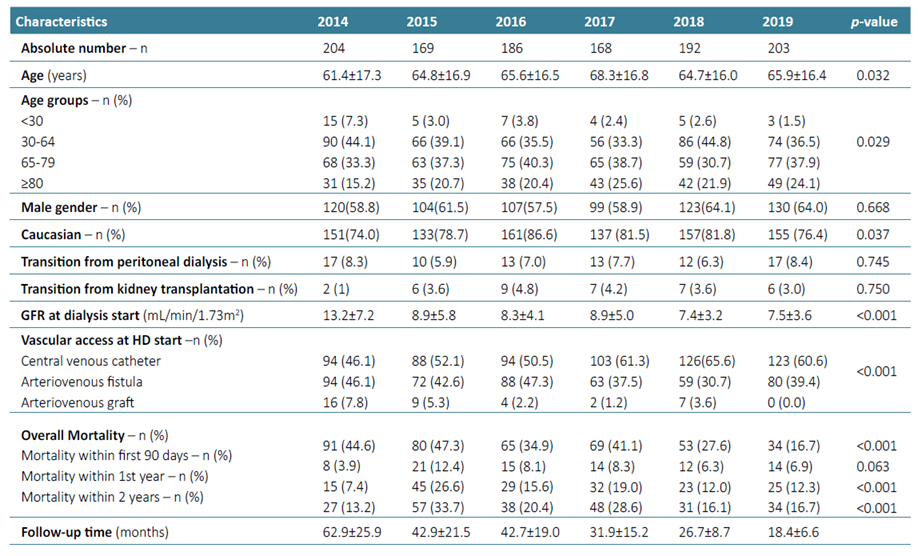

The number of patients that started HD per year varied between 169 in 2015 and 204 in 2014. The yearly patient characteristics are described in Table 2. The mean age of patients has increased significantly throughout the years (61.4 to 65.9 years, p=0.032), and the percentage of patients over 64 (48.5% in 2014, 58.0% in 2015, 60.7% in 2016, 64.3% in 2017, 52.6% in 2017, 62.0% in 2019) and over 80 (15.2% in 2014, 20.7% in 2015, 20.4% in 2016, 25.6% in 2017, 21.9% in 2018, 24.1% in 2019) increased significantly over the years (p=0.029). Furthermore, patients started HD with progressively lower eGFR, from 13.2 ±7.2 mL/min/1.73 m2 in 2014 to 7.5 ±3.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 in 2019, which was statistically significant (<0.001). Considering vascular access at HD start, the percentage of patients with central venous catheter increased (46.1% in 2014, 52.1% in 2015, 50.5% in 2016, 61.3% in 2017, 65.6% in 2018, 60.6% in 2019), while the percentage of patients with arteriovenous fistula and graft decreased (p<0.001). There was a trend for mortality rate reduction within the first 90 days (p=0.063) and a significant decline in mortality rate within the first years (p<0.001) over the years.

Patient Characteristics According to Survival

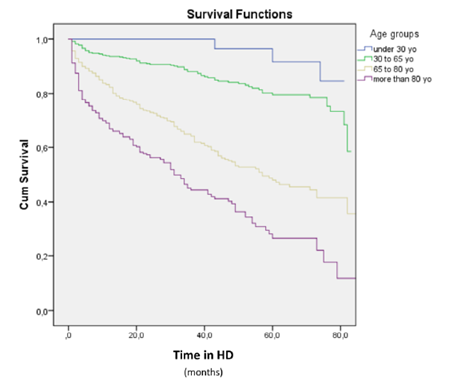

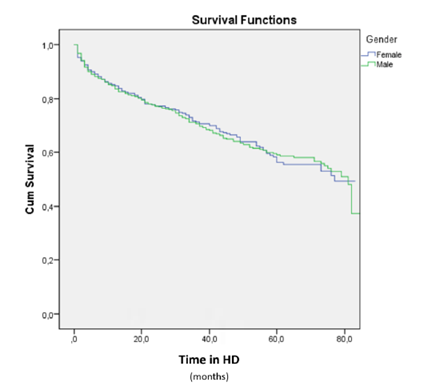

As expected, mortality was higher in older patients, as seen in Fig. 1. There was no statistically relevant association between survival and gender, as illustrated in Fig. 2. As anticipated, vascular access at HD start was significantly associated with mortality, which is demonstrated in Fig. 3 (central venous catheter: mortality 43.0%, mean follow‑up 51.3 months; arteriovenous fistula: mortality 24.3%, mean follow‑up 67.4 months; arteriovenous graft: mortality 28.9%, mean follow‑up 63.5 months; p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Our study describes a cohort of patients who started HD in a large tertiary care hospital in the Portuguese region with highest incidence of HD (Lisbon and Tagus Valley) in a recent period of time (2014‑2019).3 The mean age of our patients was similar to what was previously reported by Almeida et al - a characterization of the Portuguese HD population in 2010‑2016 - (64.9 ±16.8 years vs 65.4±16.3 years), as was the gender distribution (60.9% male vs 61.5%).3 The main causes of CKD were also in line with was previously described for the Portuguese population with the three most common causes being diabetes mellitus, unknown causes and hypertension.6

When compared to Almeida et al older cohort, we found a higher percentage of individuals transitioning from peritoneal dialysis (7.3% vs 4.4%).3 Concerning vascular access, our data is somewhat similar to the Portuguese Society of Nephrology registry most recent report (central venous catheter 56.0% vs 63.7%, arteriovenous fistula 40.6% vs 35.0%, arteriovenous graft 3.4% vs 1.3%), however with a slightly smaller percentage of patients initiating HD by central venous catheter.6 Although international data regarding vascular access is highly variable ranging from 23% to 73% according to DOPPS II, almost half the countries included had at least 50% of patients inducing by a central venous catheter.9

Concerning mortality, we found that 34.9% of our patients died during the follow‑up period, 7.5% within the first 90 days, 15.1% within the first year and 20.9% within the first 2 years of starting HD, data parallel to what was previously reported by Almeida et al study (33.1% overall mortality, 6.5% in the first 90 days, 14.8% in the first year and 21.7% in the first 2 years).3 We point out that this is not consistent with the Portuguese Society of Nephrology registry that is based in annual inquiries sent to all Portuguese nephrology centers that states a gross mortality rate of 12.5% to 14.0% between 2011 and 2021 and 4.45% within the first 90 days in 2021.6This disparity may be due to missing data from this registry, as Almeida et al work was extracted from a National Health System online platform of mandatory registration of every patient under HD and its outcomes.3 ERA‑EDTA latest registry mentions an unadjusted survival probability of 84.5% (84.3‑84.6) at one year and 72.9% (72.7‑73.1) at two years for patients in HD, which is also in line with our findings.2

In our cohort, the mean age increased significantly throughout the years, and the percentage of patients over 64 years old increased, which could be due to the increase of the life expectancy in this time period in Portugal, as well as, a higher prevalence of risk factors for CKD (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, obesity and cardiovascular disease) in this age group.10,11This could also reflect a possible tendency to initiate HD in older patients increasingly often. Similarly, United States Renal Data System reports an increasing prevalence of patients under kidney replacement therapy from 2014 to 2019.1

Even though we found no particular changes in the percentage of patients that transitioned from peritoneal dialysis throughout this period, the percentage of patients that transitioned from kidney transplantation to HD declined which might translate an improvement in graft survival or death with a functioning graft in our cohort. We also found that HD was started at significantly lower levels of eGFR, which could be attributed to a better control of CKD comorbidities, volume and nutrition status, and uremic symptomology in those previously followed by nephrologists or even a latter referral to nephrological care. This last hypothesis may also explain the increasing percentage of patients inducing by central venous catheter.

Another aspect worth mentioning was the fact that, despite the increase in elderly patients, the mortality rate within the first 90 days and first year declined, highlighting the quality of care provided, in addition to a better acknowledgment and referral to conservative care. We also point out that the number of elderly patients initiating HD in 2014 was low, which might explain why the mortality rate within the first 90 days, first one and two years were lower that year.

In our cohort, as expected, survival was more common in younger individuals and in those that initiated HD by arteriovenous access, further highlighting the importance of a timely access construction. However it should be mentioned that the association between central venous catheter and mortality bares a caveat: it may be partially due to the patients underlying comorbidities which could impair an vascular access placement or deem it superfluous and also have an impact on mortality. Furthermore, patients that initiated HD by central venous catheter are more likely to not have a previous nephrology follow‑up and start HD in a urgent setting, which may influence mortality.

There are several noteworthy limitations in our study. Firstly this is a single‑centre, retrospective observational study limiting the generalization of our results. Secondly, we did not assess the amount of patients who started HD acutely which might impact the outcome. Finally, causes of death were not evaluated which would be interesting to analyze. Nevertheless, our study has a notable sample size for a single‑centre analysis in Portugal. We also emphasize that our department gives direct support to the emergency department, which indeed might increase the percentage of acutely ill patients starting kidney replacement therapy, but also probably serves a better reflection of the general population of patients starting HD in Portugal.

To conclude, in this study the authors describe a large cohort of Portuguese patients that started HD between 2014‑2019 that correlates well with the available recent data from the national and european registries. We found the percentage of elderly patients increased thorough the studied years and, contrariwise, mortality within the first years declined, highlighting the quality of care provided. This also is in line with the increasingly higher prevalence of end‑stage kidney disease (specifically in the elderly population) reported by the registries, which emphasizes the importance of devising preventions strategies for CKD and timely referal for nephrology appointments. Further prospective studies are required to better understand the particularities of the Portuguese CKD population and the evolution of its characteristics throughout the years.