INTRODUCTION

About 850 million people worldwide are affected by some form of kidney disease, exceeding other diseases, such as diabetes, osteoarthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, or depressive disorders.1,4Chronic kidney disease is currently defined by abnormalities of kidney structure, detected by imageology or histology, or abnormalities of kidney function for three or more months, assessed by eGFR5 and the presence of one or more markers of kidney damage.

The global prevalence of CKD is rising exponentially,5,9and it is estimated to affect around one in 10 individuals3,10,13and ~100 million Europeans.2 In the Portuguese population,5,14the prevalence of stage 1 to 5 CKD is 20.9%14 and for patients of stage ≥G3a/A1 CKD is estimated to be 9.8%,5,14with women more affected. Kidney disease has become the 10th leading global cause of death and is projected to become the fifth leading cause of death and the fifth most common global cause of Years of Life Lost by 2040.10,15,16The most common causes of CKD are hypertension and diabetes, but smoking, obesity, acute kidney injury,2,11,14,17,22infectious diseases, heavy metals, industrial and agricultural chemicals, high ambient temperatures, contaminants in food or drinking water, and other ingested substances such as nephrotoxic23-24drugs are important risk factors as well. Nowadays, screening for kidney disease is recommended for high‑risk populations including those with diabetes, hypertension, and HIV, and in regions where CKD is highly prevalent due to other causes.²⁶ Although proteinuria is easy to detect and potentially reduce with appropriate medication,¹³,²⁷ its monitoring in real‑world practice is low.²⁷ While CKD is a major burden on health systems,5,14accessibility remains a major barrier to its appropriate management.28,29Although screening can easily be accomplished by measuring serum creatinine and urinary albumin, less than 10% of patients are aware of their disease.30-33It is therefore essential for physicians to be aware of CKD’s risk factors, preventive measures, screening and referral criteria.13,34There is an urgent need to develop awareness and education programs in areas of lesser investment, as well as research projects to clarify issues on which there is still no scientific consensus.33,35,36In this study we sought to evaluate the level of awareness and consensus of physicians in topics concerning the screening, diagnosis and clinical management of CKD, in order to identify which areas related to CKD should be the subject of educational or research programs.

METHODS

The Jandhyala method is a novel process for assessing proportional group awareness and consensus on responses arising from a list‑generating questionnaire37 on a specific subject between experts.38 The Jandhyala method enhances the understanding of subject matter awareness across a group of experts and provides standardized categorization of items. This focus allows for a more detailed understanding of what experts know and agree upon, making it particularly useful for identifying educational gaps and areas requiring further research. This method uses an innovative approach that is distinct from other consensus methods and has already37 been used to develop other instruments.39,40It consists of two survey rounds. In the first round, the “Awareness Round”, participants provide free‑text responses to open‑ended questions, which are then thematically coded into mutually exclusive items. These items form the basis of a structured questionnaire used in the second round, the “Consensus Round” where participants rate their agreement using Likert scales. Item awareness, observed agreement, consensus and prompted agreement are then measured.37

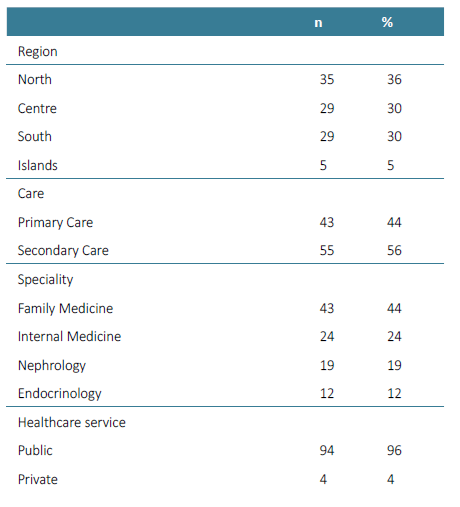

Participants and Recruitment

A total of 100 physicians from all Portuguese regions, from different clinical settings and with different specialties were recruited using convenience sampling via professional networks and were invited to participate in the study between March and May of 2022. Of these, 98 participated in the Awareness Round (Supplementary Table 1) and 96 participated in the Consensus Round, two weeks later (44 from primary care ‑ Family Medicine; and 52 from secondary care ‑ 23 of Internal Medicine, 18 of Nephrology and 11 of Endocrinology). The results were evaluated in two groups: primary care and secondary care. To be included, participants had to have experience in scientific production and have CKD as an area of interest.

Participants were informed that taking part in the study was voluntary and were given information about how to withdraw. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing information about the study and before the study began. Responses were anonymized and Consensus Round list items were not identifiable to particular participants.

Awareness Round

During the Awareness Round survey, participants were asked to respond to a series of open short‑answer questions, via online, with no limit on the number of answers. In both groups the same questions were applied, except for question number three:

What type of patient may be at increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease?

What type of patient may be at increased risk of progression of chronic kidney disease?

What are the factors that currently limit the ability to diagnose chronic kidney disease? (Primary Care)

What are the factors that currently limit the ability to treat chronic kidney disease? (Secondary Care)

What changes in clinical management in the patient after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease?

The responses to the Awareness Round questionnaire were used to assess knowledge awareness by calculating the frequency of each coded item in relation to the overall most frequently occurring coded item ‑ the Awareness Index (AI). The compiled list of items were reviewed and refined by the investigators and included in Consensus Round as structured questionnaires.

Consensus Round

The participants who completed the Awareness Round were asked to participate in the Consensus Round online survey. They were asked to rate their level of agreement with the statements from the Awareness Round survey, using a five‑point Likert scale (Strongly agree, Agree, Neither agree nor disagree, Disagree, and Strongly disagree). Responses to the structured questionnaire in Consensus Round were used to determine observed consensus, proportional group awareness and the effect of prompting, i.e. persuasion after reading all items collected in Awareness Round.

The Consensus Index (CI) was calculated as the percentage of participants who agreed or strongly agreed with each statement in the Consensus Round.

Index Score (Jandhyala Score)

The Index Score was used to measure prompting during the Consensus Round. The concept of prompting was pre-specified to have occurred if the absolute difference between the AI and the CI was 0.05 (or 5%). Unprompted consensus was defined when a majority of participants suggested an item during the Awareness Round, and a majority of participants subsequently agreed or strongly agreed that the item was important in the Consensus Round. Any item that during the Awareness Round was suggested by only a few participants but was deemed to be important in the Consensus Round was considered as completely prompted.

Items with a CI >50% indicate that some education may be required in order to increase awareness about that item. Items with a CI <50% may indicate an opportunity to redefine these norms. The index score identifies items or areas either where more education is required (in the case of items not listed by the participants or listed by very few of them in the Awareness Round) or where more research is required (in the case of no observed agreement consensus for a statement in the Consensus Round).

The purpose of this methodology is not to force a consensus, but to evaluate the current knowledge and opinions of the selected experts. In order to have an opinion from which to form a consensus, a group of experts must first be aware of the key aspects of the subject of interest - without one there cannot be the other. The expert responses to the structured questionnaire allow the investigators to observe any consensus that arises and determine whether it is prompted or unprompted. The advantage of the anonymity of the participating experts mitigates the effect of dominant individuals, manipulation or compulsion to confer to certain viewpoints and preserves the independence in item generation during the Awareness Round.

RESULTS

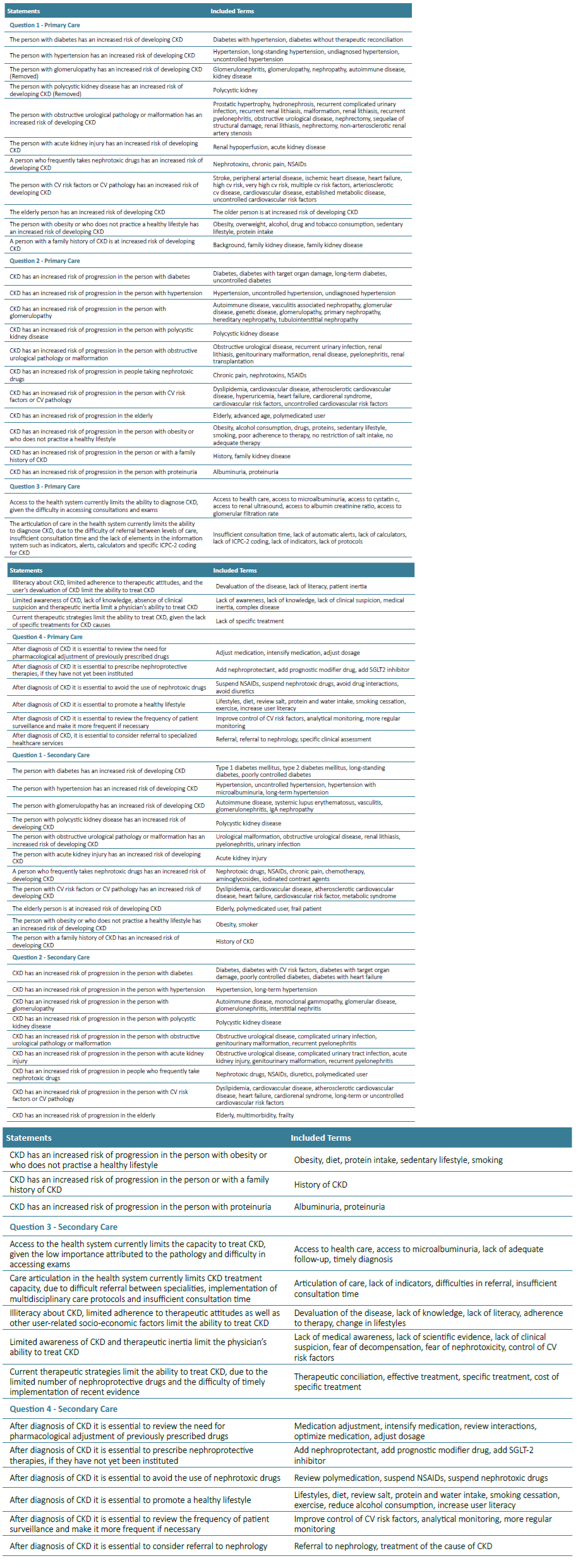

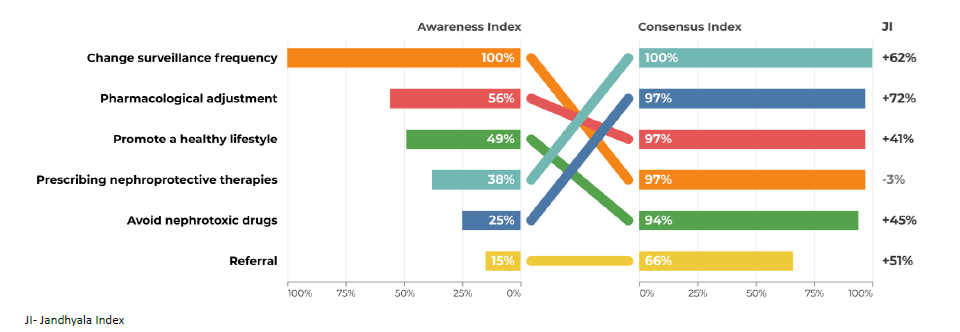

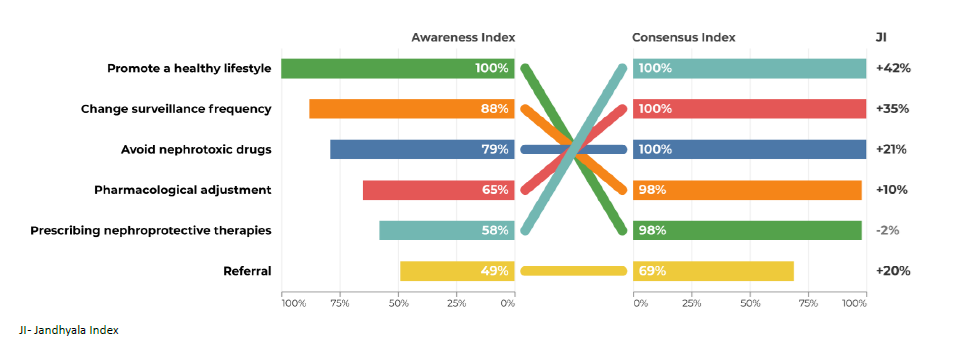

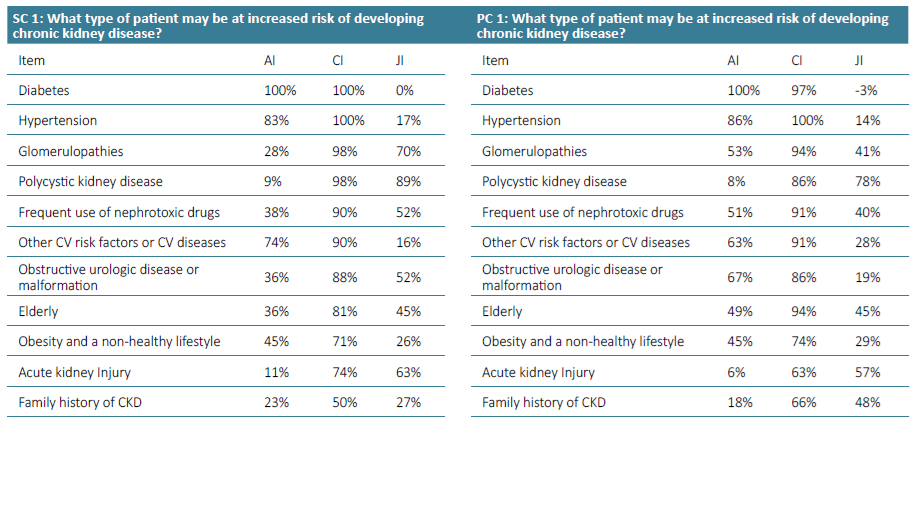

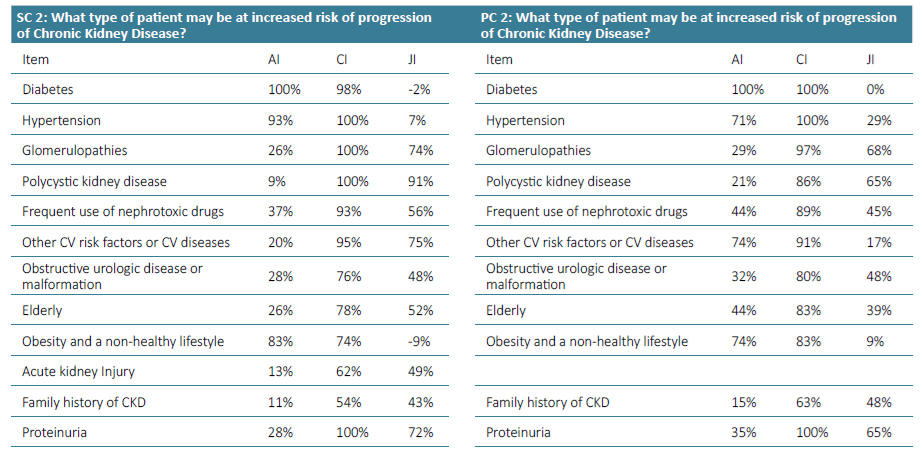

After the two rounds, it was found that several items not mentioned by the participants in the Awareness Round (Table 1) obtained a high consensus index. In questions 1 and 2, there was agreement between the results obtained in the two groups ‑ primary and secondary care. On the other hand, questions 3 and 4 generated more disagreement (Figs. 1‑8 and Supplementary Tables 2‑5).

Supplementary Table 2. Awareness Index (AI), Consensus Index (CI) and Jandhyala Score (JI) of Question 1 for Secondary care (SC) and Primary care (PC).

Supplementary Table 3. Awareness Index (AI), Consensus Index (CI) and Jandhyala Score (JI) of Question 2 for Secondary care (SC) and Primary care (PC).

Supplementary Table 4. Awareness Index (AI), Consensus Index (CI) and Jandhyala Score (JI) of Question 3 for Secondary care (SC) and Primary care (PC).

Supplementary Table 5. Awareness Index (AI), Consensus Index (CI) and Jandhyala Score (JI) of Question 4 for Secondary care (SC) and Primary care (PC).

Awareness Round

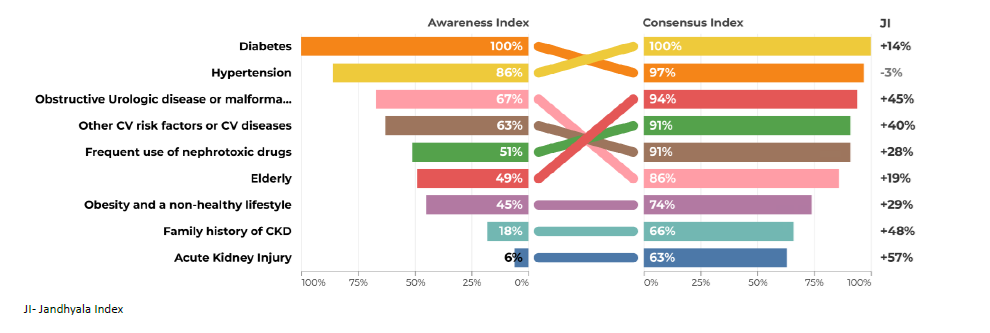

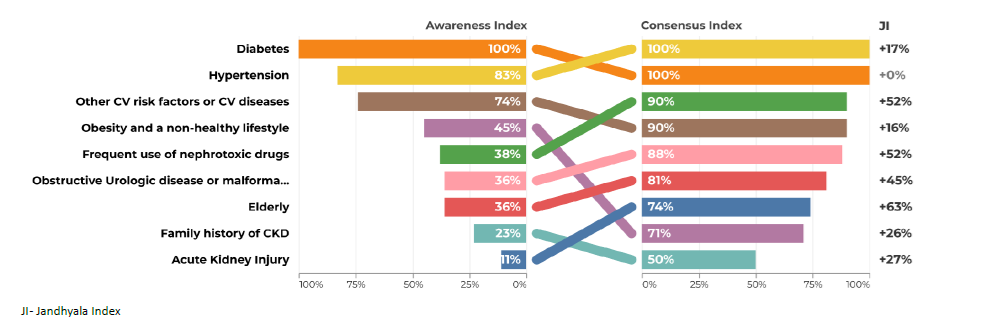

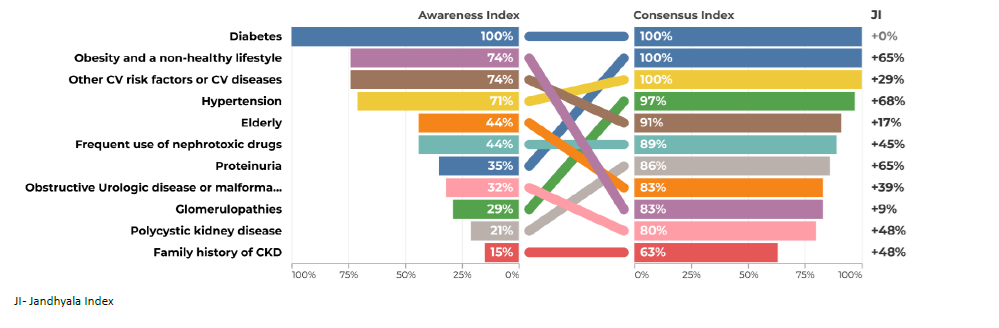

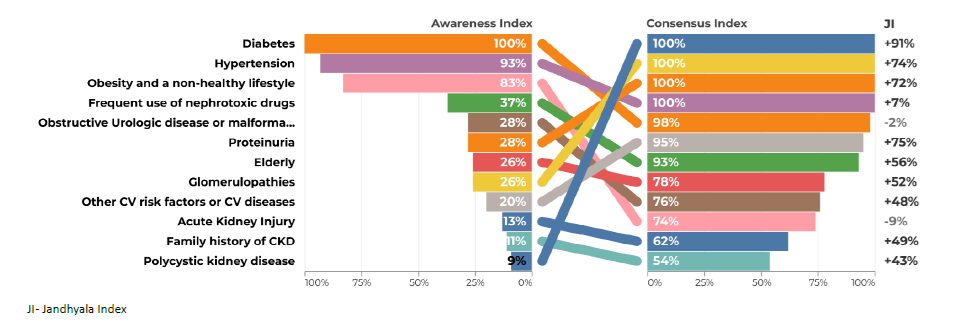

The most frequently mentioned items in questions 1 and 2 were diabetes and hypertension (Figs. 1 to 4). Regarding question 1 ‑ What type of patient may be at increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease - diabetes was the most frequently mentioned, with an AI of 100% (Figs. 1 and 2). Family doctors referred to glomerulopathies more often than the colleagues from the hospital (53% vs 28%). Polycystic kidney disease had a very low AI in both groups of physicians (9% and 8%). Glomerulopathies and polycystic kidney disease are considered to be chronic kidney diseases themselves and many participants did not refer to them in the Awareness Round because they considered them part of CKD, leading to a false low AI. In the first question, the items mentioned should include risk factors and not different etiologies of CKD. For this reason, these two items were not included in the Consensus Round.

Acute kidney injury also had a very low AI in primary and secondary care (6% and 11%).

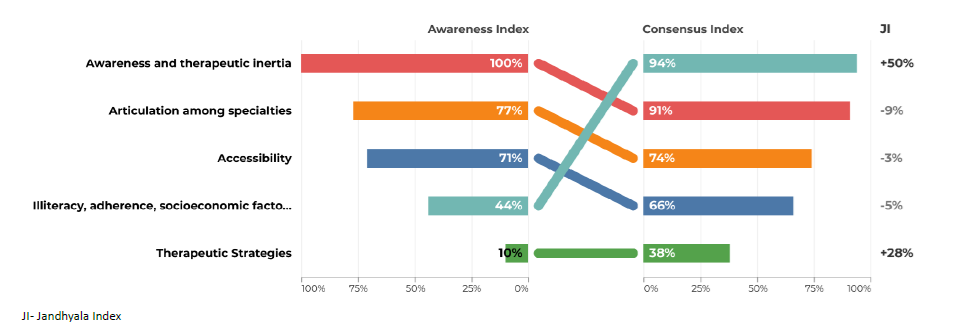

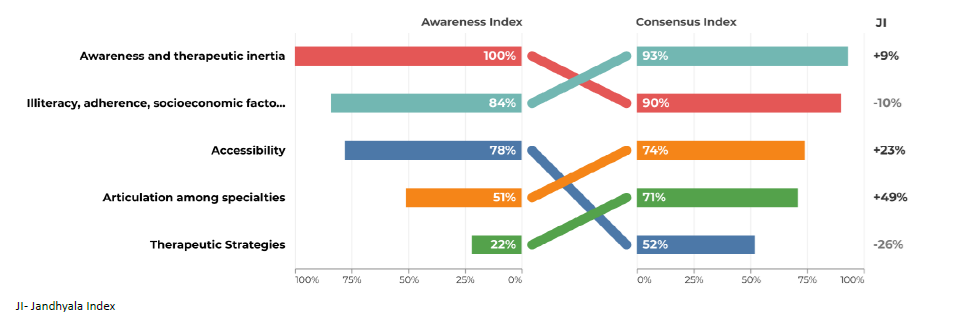

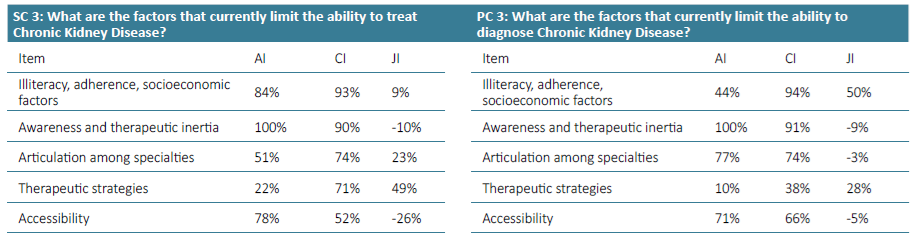

Regarding question 2 ‑What type of patient may be at increased risk of progression of chronic kidney disease ‑ diabetes and hypertension were the most frequently mentioned items by both groups, although in the group of primary care, hypertension only reached an AI of 71% (Figs. 3 and 4). Urologic disease had an AI of 28% by the secondary care specialties but reached 50% by family doctors. Proteinuria reached an AI of 28% in the secondary care specialties and 35% in primary care. Glomerulopathies also had low AI of 26% and 29%. Acute kidney injury had an AI of 35% in the secondary care group, but no awareness from primary care. Polycystic kidney disease also had very low AI among secondary care specialties (9%), but a higher one among family doctors (21%). Regarding question 3 for primary care ‑ What are the factors that currently limit the ability to diagnose chronic kidney disease ‑ the most common item was considered to be the physician’s inertia (AI 100%) and the second one was the lack of coordination between the various departments and primary and secondary care (AI 77%) (Fig. 5). In secondary care, (What are the factors that currently limit the ability to treat chronic kidney disease?), therapeutic inertia was also the item with the highest AI and the second one with an AI of 84% was illiteracy, adherence, socioeconomic factors (Fig. 6).

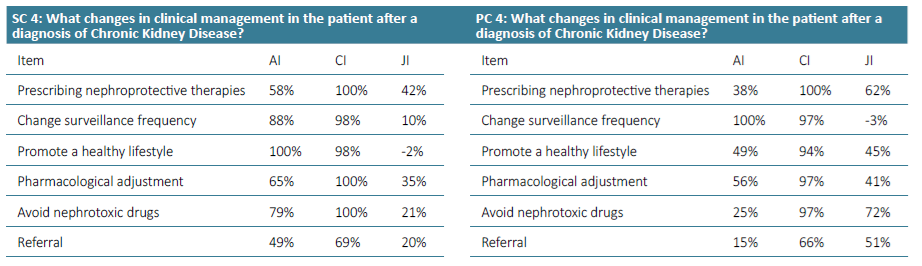

Regarding question 4 ‑What changes in clinical management in the patient after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease ‑ promoting a healthy lifestyle had an AI of 100% by secondary care specialties, but only 49% AI in primary care. The avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs had an AI of 79% in secondary care, but only 25% in primary care (Figs. 7 and 8).

Consensus Round

All items generated from the Awareness Round were retained in the final measure, except Glomerulopathies and polycystic kidney disease in the first question. Most of the participants agreed or strongly agreed with the statements generated during the Awareness Round (Table 1). The AI, the CI and the Index Score or Jandhyala Score can be seen in Figs. 1 to 8. Regarding question 1 ‑ What type of patient may be at increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease ‑ diabetes had a CI of 100% in secondary care specialties and 97% in primary care, although Hypertension had a CI of 100% in both groups (Figs. 1 and 2). Some items showed a low AI, but a high CI, with a consequent high Index score, such as glomerulopathies, polycystic kidney disease and acute kidney injury.

Regarding question 2 ‑ What type of patient may be at increased risk of progression of chronic kidney disease ‑ glomerulopathies, polycystic kidney disease, nephrotoxic drugs, obstructive urologic pathology or malformation, acute kidney injury, elderly people, obesity and a non‑healthy lifestyle and proteinuria showed a low AI but a high CI and consequent high Index score (Figs. 3 and 4).

Regarding question 3 for primary care ‑ What are the factors that currently limit the ability to diagnose chronic kidney disease ‑ illiteracy, adherence, socioeconomic factors was the item with the highest index score of 50% (Fig. 5). In the secondary care group, in question 3 (What are the factors that currently limit the ability to treat chronic kidney disease?), the item with a higher Index score was therapeutic strategies (49% (Fig. 6)).

Regarding question 4 ‑ What changes in clinical management in the patient after a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease? ‑ in primary care, prescribing nephroprotective drugs, avoiding nephrotoxic drugs and referral had a low AI and a higher CI and Index Score, while in secondary care, the index scores were much lower (Figs. 7 and 8).

DISCUSSION

Disease Illiteracy

In general, the results showed a low awareness of some diseases, such as polycystic kidney disease, although it is responsible for 10% of end ‑stage renal disease (ESRD).41 We consider that its low frequency, hereditary nature, and high family clustering may lead to early referral to nephrology appointment, so non‑nephrologist colleagues may follow a reduced number of patients with this disease. The same circumstance may happen with some glomerulopathies, which are important causes of ESRD, but had a low AI in questions 1 and 2. Another explanation is the fact that these entities are considered to be chronic kidney diseases themselves and many participants did not refer to them in the Awareness Round, because they considered them part of CKD, leading to a false low AI. Development and progress may be misleading terms and there were different interpretations of the first question. Therefore, the items of polycystic kidney disease and glomerulopathies were removed from the Consensus Round in the first question.

A low AI of AKI as a risk factor for development and progression to CKD proved its under ‑recognition as a cause of CKD, although patients with AKI have a 9‑fold higher risk of CKD and 3‑fold higher risk of ESRD.42 The diagnosis of AKI occurs frequently in the nephrology/internal medicine setting, which leads to low exposure of non‑nephrologist colleagues to the common and validated phenomenon of the AKI‑CKD transition.

A low AI of proteinuria and glomerulopathies as contributors to CKD progression confirmed its low recognition. They are both relevant factors for progression, although proteinuria is common in several kidney disease mechanisms, including not only glomerulopathies but also other diseases. Thus, there is an opportunity to emphasize its role as a marker for diagnosis, progression and therapeutic target for CKD (anti‑proteinuria therapies), with an impact on the reduction of renal outcomes. The presence of proteinuria is associated with 10‑fold higher risk of CKD progression and 5‑fold higher risk of ESRD.43 A focus on expanding screening and longitudinal monitoring of proteinuria in primary care is essential and there should be protocols that would allow both greater adherence and better management of kidney disease by clinicians. In the case of glomerulopathies, the eminently nephrological nature and their relatively low prevalence partially explains these results.

In the future, awareness campaigns on risk factors for CKD should be conducted. We propose developing focused training programs on critical areas of CKD management, conducted through online modules, short workshops, or integrated into continuing medical education (CME) programs. Also, awareness‑raising activities in schools, workplaces, and community centers, supported by local health organizations, and comprehensive public awareness campaigns using various media channels can further increase understanding of CKD and early detection.

Referral/Networking

Access to health care had a medium AI and a lower CI, probably due to different points of view, depending on the department. It may be due to some difficulty in accessing nephrology appointments in some hospitals and also the low access in primary care, leading to a low diagnosis rate. Referral is the item where there is a lower CI, especially in primary care. This result may reflect different interpretations from different departments. Referral depends on the stage of CKD, its risk of progression, and access to a medical specialist. Aging is a significant risk factor for CKD, particularly in societies with a growing elderly population. Despite its importance, the role of aging in CKD is often underrecognized. Addressing this gap, it is crucial to implement targeted interventions for the elderly, including regular screening, early detection, and management of CKD, to improve outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Chronic kidney disease stages and their adjustment for age should be discussed as well as the criteria for referral of CKD to nephrology. There is a need to review the inter‑specialty referral criteria and a practical guide on CKD diagnosis and its different etiologies should be promoted.

Disease Management and Treatment

In question 3, awareness and therapeutic inertia had a high AI and CI, which represents a recognition of sometimes inadequate perception of the problem by colleagues and failure to apply appropriate diagnostic measures. More‑ over, the intrinsic limitation of creatinine and GFR formulas to detect incipient forms of CKD (particularly in elderly, highly comorbid and malnourished patients) and low adherence to serial assessment of proteinuria are aspects to be taken into account. Therapeutic strategies had a low AI in both groups, but especially in the primary care. While both primary and secondary care physicians are involved in both diagnosis and treatment processes, their day‑to‑day activities differ. Primary care focuses on early detection, ongoing monitoring, and initial management of CKD to ensure timely and accurate diagnoses. In this sense, therapeutic strategies play a minor role in the diagnostic capacity of CKD. In contrast, secondary care, concentrates on advanced treatment adjustments and managing complications. Understanding these distinct but complementary roles is crucial for optimizing CKD management across the healthcare continuum. Therefore, there is a need to strengthen communication between these two players. Promoting internships and training programs in Nephrology departments and in Primary care facilities for medical students and overall healthcare professionals, along with continuous education opportunities, can enhance practical knowledge and skills in CKD diagnosis and management. Additionally, mobile health applications can help patients monitor their health, receive medication reminders, and access educational content, supporting self‑management and treatment adherence. Utilizing electronic alerts to signal the achievement of a certain GFR threshold and easier and quicker referrals to nephrology is also a strategy to be considered.

In question 4, the use of nephroprotective drugs has a high CI, but a low AI. Training courses and interdisciplinary meetings in which the different specialties involved in the diagnosis and treatment of CKD can discuss strategies and create therapeutic algorithms adapted to the characteristics of subgroups of patients should be promoted. For example, it would be important to have pain management protocols for patients with chronic pain. In these protocols, nephrotoxic drugs with analgesic effects, such as NSAIDs, would be avoided and in patients with regular and high consumption of NSAIDs, regular CKD screening should be considered.

The promotion of a healthy lifestyle is one of the fundamental pillars of the work of primary health care professionals. Due to its transversality, it may not have been initially associated with the specific area of CKD, justifying the lower AI obtained.

Therapeutic adjustment, with the avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs and the implementation of nephroprotective measures, is essential in the management of CKD. A proposal for the future is to conduct a systematic review based on international guidelines to create an algorithm for the management of CKD at the primary care system and across different specialties.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study were the inclusion of a high number of experts, from all over the country and from various specialties with different views of CKD. Since the topic presented several interpretations, starting from an open questionnaire allowed us to see the main areas of interest of the expert panel. The main limitation was the difficulty of categorizing the items from Awareness to Consensus Round. In the Awareness Round, participants answered open ‑ended questions, leading to many different answers that were difficult to integrate into categories. Additionally, the Jandhyala method allows a maximum of two rounds and no face‑to‑face meetings, denying the opportunity to discuss pertinent topics.38

CONCLUSION

Based on our results, there are some measures, such as educational programs, that can be taken in order to increase awareness of some items, specifically polycystic kidney disease, glomerulopathies and acute kidney disease. There was a recognition of sometimes inadequate perception of the problem by colleagues and failure to apply appropriate diagnostic measures and also a need to review the inter‑specialty referral criteria. These results seem to call for the implementation of initiatives focused on CKD referral and management.

There is also a need to train physicians to potentiate action for CKD in areas of high consensus and identify areas of disagreement.

The results also stress the need to advocate for equitable and affordable access to the entire spectrum of kidney care everywhere. Based on our study, we believe there is a high likelihood of success in implementing outreach projects or initiatives focused on CKD literacy, referral and disease management.

LEARNING POINTS/TAKE HOME MESSAGES

We detected a low awareness of polycystic kidney disease, glomerulopathies and acute kidney disease in healthcare professionals;

There was a recognition of sometimes inadequate perception of the problem by colleagues and failure to apply appropriate diagnostic measures and also a need to review the interspecialty referral criteria;

Based on our results, we consider there is a high likelihood of success in implementing outreach projects or initiatives focused on CKD literacy, referral and disease management.