INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, hemodialysis is the cornerstone treatment for kidney failure, and Portugal is the European country with the highest unadjusted prevalence of people being treated with this kidney replacement therapy.1 However, the personal, familial, societal, and economic implications of hemodialysis are extensive, leading to heightened psychological distress and a significant decline in the quality of life of the person receiving this (often long‑term) treatment and their close family members.2

Renal Psychology is the clinical specialty that focuses on understanding and addressing the psychological (i.e., behavioural, cognitive, emotional, social, and existential) strains arising from living (or caring for a significant other dealing) with kidney diseases and treatments.3 In the last two decades, Renal Psychology has gained increasing recognition in the international scientific literature largely due to the growing body of studies highlighting the complex interplay between the medical and psychosocial challenges faced by individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD).4-6In the context of hemodialysis, cumulative research has evidenced that mental health issues negatively impact patient treatment adherence, raising the risk of dialysis‑related complications, healthcare utilization and costs, and early mortality.4-6Conversely, psychological interventions have been shown to enhance patients/ families’ knowledge, confidence, and skills to effectively cope with the demands of kidney therapies over time.7,8In this regard, different meta‑analyses have confirmed that the timely implementation of psychological interventions in nephrology centres is associated with more favourable clinical and laboratory outcomes like interdialytic weight, blood pressure, and serum levels of haemoglobin, albumin, phosphorus, and potassium.8-11Patient participation in these approaches also helped to alleviate adverse physical and psychological symptoms, such as pain, fatigue, insomnia, and depression, and reduce medication overuse.6,7Similar findings have been reported by recently published systematic reviews underlining the advantages of the few available psychological interventions for improving quality of life and reducing caregiver burden in people caring for a family member with kidney failure.12,13Despite this awareness, the presence of mental health professionals continues to be utterly insufficient in most nephrology centres worldwide,14 including in Portugal, where the role of Renal Psychologists and the implementation of psychological interventions in dialysis units remains severely underprioritized.15,16This shortfall is particularly evident when compared to other European countries like Spain (Fundación Renal Española; https://fundacionrenal.com), France (France Rein, https://www.francerein.org), and the United Kingdom, which already have an active workforce of Clinical Health Psychologists in nephrology care settings. For instance, in the UK, organizations like the UK Kidney Care (https://kidneycareuk.org/) ensure free counselling services for people with CKD and their families, and several hospitals have already settled Renal Psychology Services to optimize the access of this population to professional psychological support.14 Progressively recognized as an international reference in Renal Psychology, this country also stands out for having created the Renal Psychological Therapists Network (https://www.renalpsychologicalther-apists.org/), an official group of Renal Psychologists who contribute to strengthening the national advancement of this clinical specialty, advocating for the inclusion of mental health professionals in interdisciplinary nephrology teams.

Innovatively, in December 2023, the Portuguese Government approved the National Strategy for the Promotion of Kidney Health and Integrated Care in Chronic Kidney Disease 2023‑2026 and created the Implementation Commission of the National Strategy for Chronic Kidney Disease (CIMEN‑DRC) that includes a representative of the College of Portuguese Psychologists (OPP - Ordem dos Psicólogos Portugueses) in an attempt to establish sustainable inter-disciplinary healthcare collaborations to meet the multifaceted assistance and informational needs of people diagnosed with chronic kidney disease and their families (Diário da República n.º 237/2023, Série II de 2023‑12‑11, pp. 102 - 107). Regardless of this much-needed and urgent initiative, little to no evidence is available to inform best practices in Renal Psychology, delimit its field of intervention, and prompt changes in national healthcare policies to include professional psychological support as a reimbursable service within state‑funded dialysis units in Portugal. The present work outlines the planning and implementation of a research project entitled Together We Stand (https://togetherwestand.pt/) that focused on developing, implementing, and testing the effectiveness of evidence‑informed disease management interventions in hemodialysis with the ultimate goal of strengthening psychological assessments and interventions in Portuguese dialysis centres. Since the contributions of this research

project may be transversal and applicable to other cultural contexts/countries, the global drive of this review article is to help raise awareness of the importance of reinforcing the incorporation and continuous training of Clinical Health Psychologists in renal care settings and to assist in promoting Renal Psychology as a field for research and clinical practice both nationally and internationally. The main empirical endeavours presented stemmed from the research work undertaken by an interdisciplinary team with extensive expertise at the intersection of Clinical Health Psychology and Nephrology in Portugal (https://togetherwestand.pt/team/?lang=en).

ORGANIZING RENAL PSYCHOLOGY PRAC‑ TICES IN PORTUGUESE DIALYSIS CENTRES

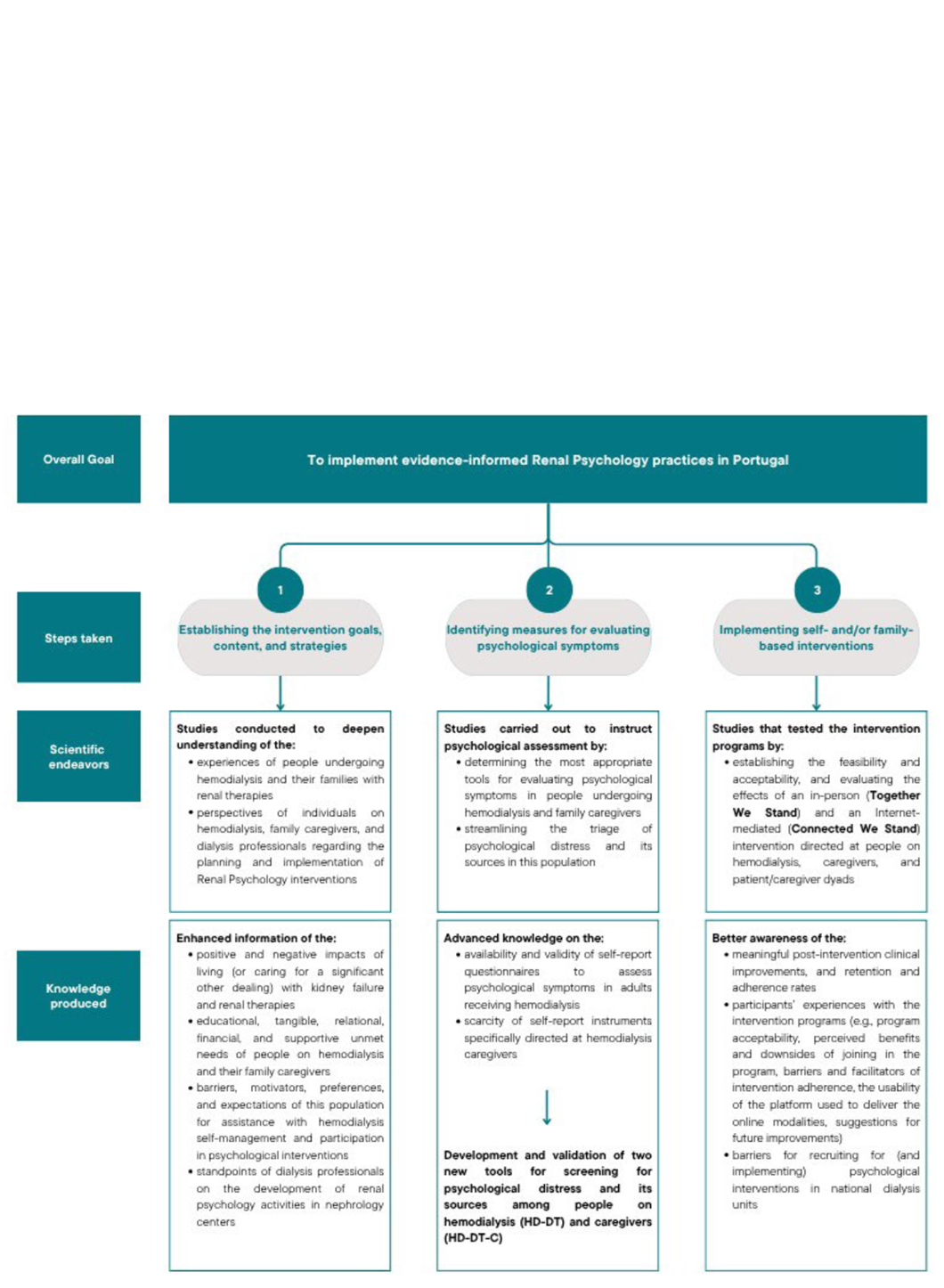

Fig. 1 summarizes the stepwise approach that was followed to instruct the planning of evidence‑informed psychological assessments and interventions in Portugal.

Step 1: Designing and implementing psychological interventions in hemodialysis

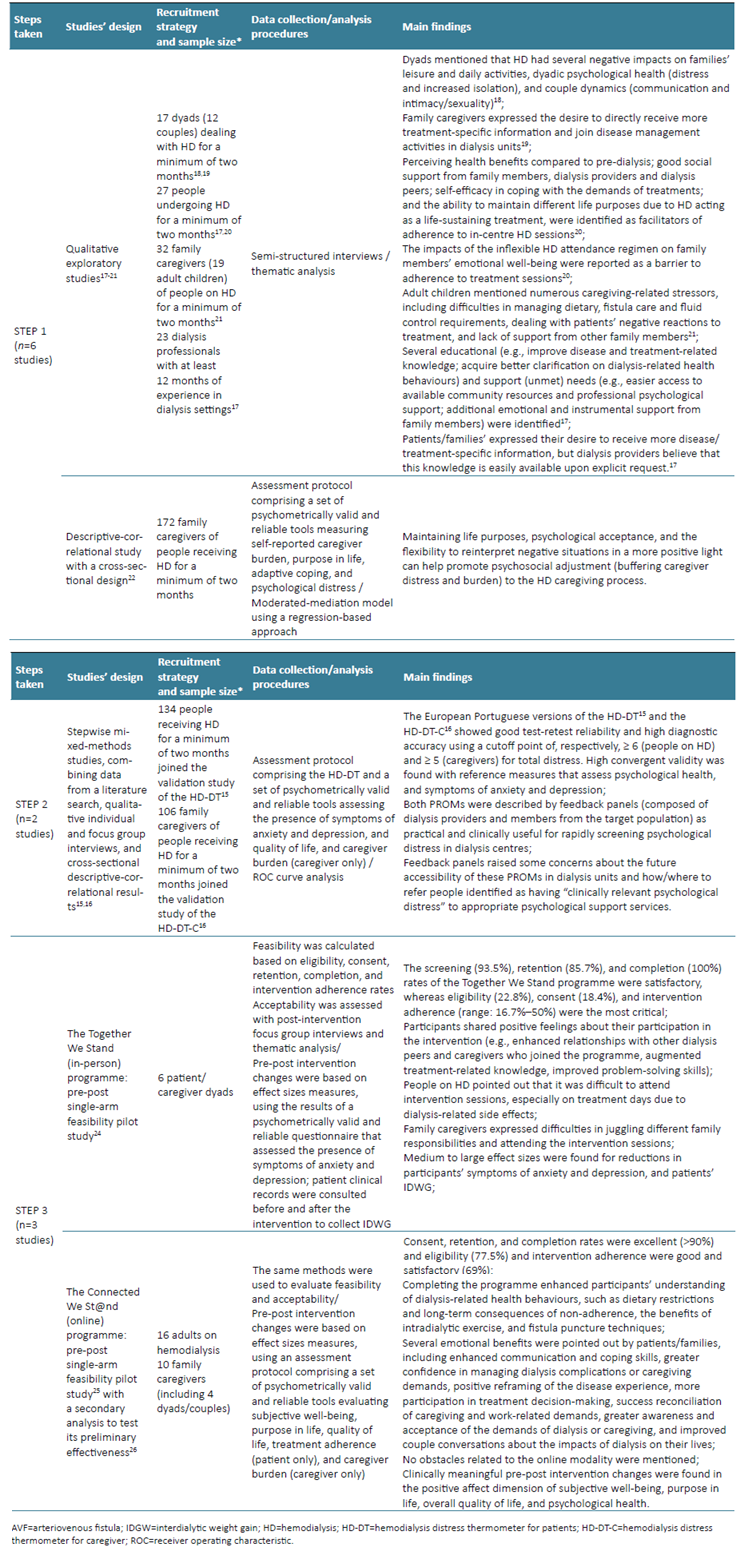

The first task consisted of collecting and analysing the individual and dyadic views of people with kidney failure and their family caregivers regarding the impacts of hemodialysis in their lives, as well as the perspectives of dialysis providers about the implementation of psychological interventions in nephrology care contexts. Table 1 summarizes the research methods and scientific results of the studies that guided the design and implementation of psychological interventions in hemodialysis (cf. Step 1).

Based on these scientific efforts, the main aspects to be addressed in psychological interventions in this context were compiled.17-22In general, such initiatives need to consider: (i) refining patients’ and caregivers’ (and dialysis care professionals’) communication skills and emotional management skills; (ii) increasing their psychological flexibility to cope with uncertainty about the future and treatment‑related (or caregiving‑specific) fears and expectations, including with kidney transplantation; (iii) and training patients/caregivers adaptive strategies to cope with the adverse effects of dialysis such as neurocognitive changes, sexual/intimacy problems, needle distress and fistula setbacks, body image and identify issues, caregiver burden, sleep impairment, and strained family relationships.17-22Findings also helped to anticipate barriers that may hinder the availability and interest of patients/caregivers in joining face‑to‑face psychological interventions in dialysis units, particularly the geographic distance and travel costs to the intervention site, scheduling conflicts with treatment sessions or other life responsibilities, the burden of dialysis treatments, and dealing with intra or inter dialysis adverse effects while receiving this type of assistance.17,23Awareness of these caveats has encouraged the planning of alternative intervention modalities, particularly Internet‑mediated approaches (cf. Step 3), which may be easier to implement and more viable and practical for this typically overburdened population.17,23-25Overall, the knowledge obtained in this initial step was used to delineate the intervention content, goals, and strategies, as well as its most convenient periodicity, duration, format, and mode of delivery.

Table 1. Research methods and main scientific results of the studies conducted to strengthen evidence informed Renal Psychology practices in Portuguese dialysis units.

* In all studies, participants were included based on the following criteria: i) being 18 years of age or older; ii); not suffering from any visual, auditory, or cognitive impairment that could hinder understanding the purpose of the study; and iii) agreeing to participate voluntarily. Those who joined the qualitative component of the project17-21were recruited from two private peripheral dialysis units in the North and Centre of Mainland Portugal; in turn, patients and caregivers who participated in the quantitative studies15,16,22were recruited from four private peripheral dialysis units in the North and Centre of Mainland Portugal. For the in‑person intervention - the Together We Stand programme23 - dyads were recruited from one private peripheral dialysis unit in the North of Mainland Portugal. For the online intervention - the Connected We St@nd programme24,25- participants were recruited using nationwide advertisements placed on social media platforms, newspapers, and mailing lists of support associations.

Step 2: Streamlining psychological assessment in hemodialysis

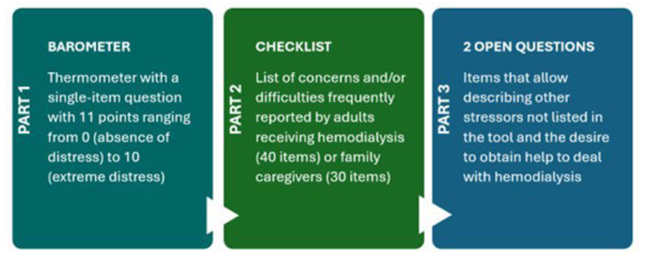

Research conducted during this second step exposed the dearth of existing self‑report measures specifically developed to identify psychological strains in hemodialysis.15,16Traditionally, in this context, a combination of non‑disease‑specific tools has been used to allow for a more comprehensive evaluation of the diverse symptoms and stressors faced by individuals with kidney failure and their caregivers; however, such practices can be time‑consuming and unfeasible, increasing the likelihood of over‑ or under‑identifying psychosocial issues and potentially delaying interdisciplinary efforts to help prevent adjustment struggles in this population.15,16Attempting to help bridge this gap, two easy‑to‑complete, clinically useful, valid, and reliable patient‑reported outcome measures (PROMs) - the Hemodialysis Distress Thermometer for Patients (HD-DT15) and the Hemodialysis Distress Thermometer for Caregivers (HD-DT-C16) - were developed and validated to simplify the triage of psychological distress and its sources (physical, emotional social/family, and dialysis‑specific) in hemodialysis. Table 1 presents the research methods and scientific results of the studies reporting the development and testing of the measurement properties of the HD‑DT and HD-DT-C (cf. Step 2). The HD‑DT and the HD‑DT‑C can be used as a starting point to encourage communication between dialysis providers and patients/families about the challenges of kidney therapies, identify the most prevalent difficulties and/ concerns of this population, and determine their need/ desire for referral to the most suitable (and available) support services.6,7Both PROMs are available in European-Portuguese (original version), American-English15,16and Turkish.26 The translation, cultural adaptation, and validation to Brazilian‑Portuguese, Australian‑English, and Chinese are currently in progress. Fig. summarizes the structure of the HD-DT15 and the HD-DT-C16

Step 3: Testing and implementing psychological interventions in hemodialysis

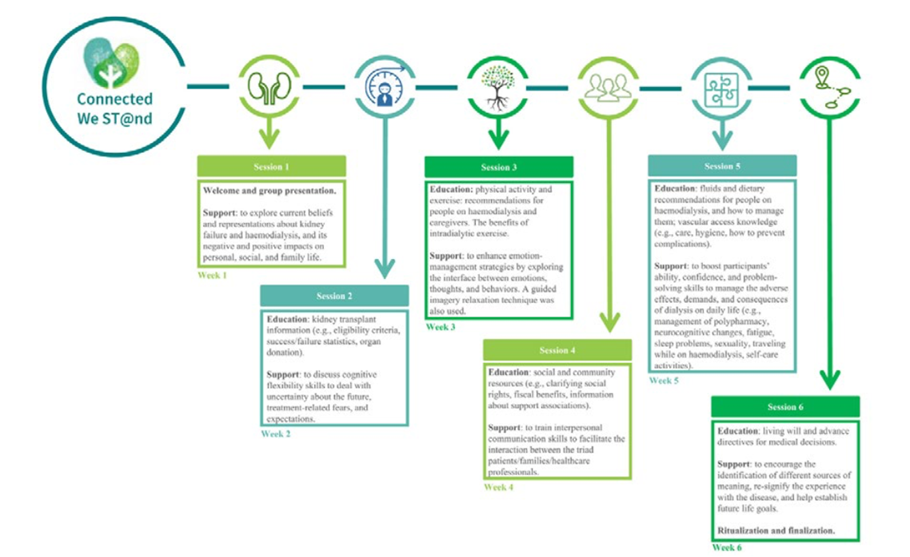

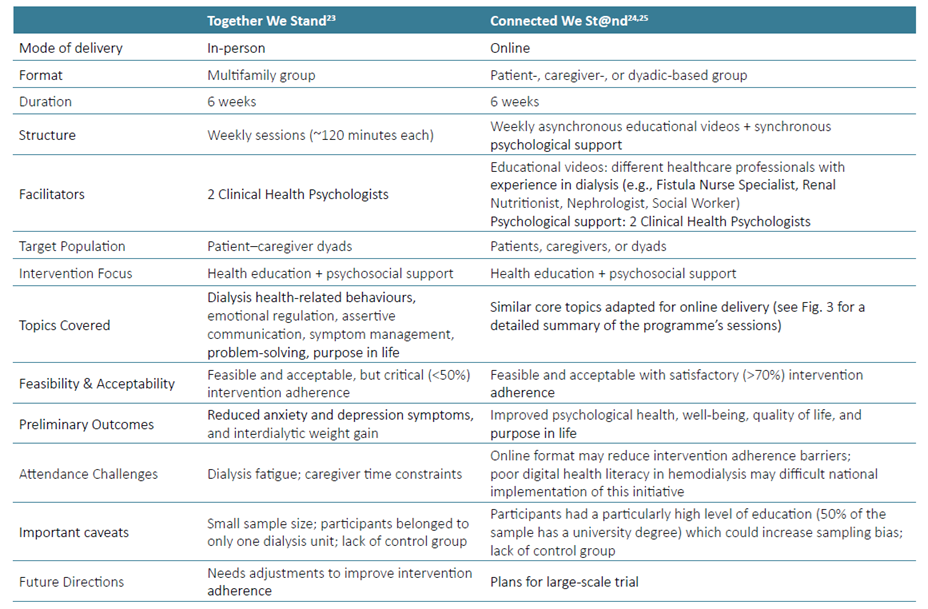

Table 1 gathers the research methods and scientific results of the studies that focused on designing, evaluating, and implementing two evidence‑informed interventions that aimed to boost successful disease management among individuals on hemodialysis and their caregivers (cf. Step 3). More specifically, two psychoeducational interventions were organized, executed, and tested, namely the Together We Stand programme,23 a face-to-face family-based approach carried out in a dialysis unit in the North of Mainland Portugal; and the Connected We St@nd programme, an Internet‑mediated intervention nationally implemented that, innovatively, can be offered as a patient, caregiver, or dyadic based group initiative (e.g., couple‑oriented), depending on participants’ preferences and needs.24,25 Table 2 compares the key components of the Together We Stand and the Connected We St@nd intervention programmes. Fig.3 presents the Connected We St@nd programme, session by session.24,25Currently, efforts are being made to proceed with a large‑scale trial of this technology‑assisted intervention to, in due course, encourage its dissemination and integration into routine nephrology practices.

Table 2. Side-by-side comparison of the main features of the Together We Stand23 and of the Connected We St@nd24,25intervention programmes.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This review article provides important information about psychological assessments and interventions in hemodialysis, recommending three nationally developed evidence informed resources that can be easily integrated and regularly implemented in dialysis centres: the HD-DT,15 the HD-DT-C,16 and the Connected We St@nd programme.24,25Notably, the Connected We St@nd programme is, to date and as far as known, the first evidence-informed, Internet-mediated, interdisciplinary, disease management intervention with evidenced feasibility and acceptability among people on hemodialysis and their caregivers, with the possibility of being available as a dyadic‑oriented practice. Particularly during/after the COVID‑19 pandemic, digital health services have exponentially grown and become a convenient and pragmatic way to deliver care to high‑risk populations, such as people with kidney failure on hemodialysis and their families, with promising results in terms of recipient/facilitator satisfaction in different clinical settings.27-29In hemodialysis care contexts, technology-assisted practices offer the prospect of smoothing patient/ family access to psychological assessments and/or interventions by minimizing restrictions related to the logistical, financial, and time burden of traveling to the intervention site, interferences with work‑related impediments, scheduling conflicts with dialysis sessions and/or other medical appointments, and difficulties in managing (or caring for someone experiencing) treatment-related adverse effects, including (but not restricted to) fatigue, pain, dizziness, and reduced functional independence.17,23-25,29Despite the potential benefits of implementing online or in‑person psychological practices in renal care settings, hemodialysis is one of the costliest treatments for healthcare systems globally.30 In Portugal, kidney failure represents a heavy burden on the National Health Service (SNS), with recent reports stating that expenses with hemodialysis are estimated to have reached around 300 million euros of the 2022 Portuguese State Budget,31,32which can make it difficult to allocate resources to integrate Renal Psychologists as part of interdisciplinary nephrology care teams. In this sense, it is worth stressing that psychological interventions are effective in improving adherence to complex therapeutic regimens, which is the case of hemodialysis adherence requirements.33,34 Improved adherence in this kidney therapy may, in turn, reduce the use or intensification of dialysis‑related polypharmacy, like phosphate binders, potassium‑lowering agents, or antihypertensives,17-18typically ensured by dialysis units within the comprehensive and integrated care payment model funded by the Portuguese National Health Service.31,32Still, to date, the cost‑effectiveness of implementing professional psychological interventions in this context remains undetermined, and more research is needed to assess how equipped and inclined nephrology centres are, both nationally and internationally, to advance Renal Psychology.29 Having this knowledge may be useful to stimulate the development of human-rights-based approaches on public health grounded on scientific evidence and professional practice that would be crucial to enhancing the quality of life of people receiving hemodialysis and their family caregivers.29

Future Challenges for Renal Psychology in Portugal

Research carried out in Portugal shows that patients and caregivers are willing to participate in routine psychological assessments and flexible disease management intervention programmes, indicating that there is great acceptability and potentially high clinical utility in implementing such initiatives in national dialysis centres.15,16,24,25Altogether, the scientific endeavours outlined in this review article confirm the importance of channelling future investments towards the organization and/or strengthening of psychological support services and investigations in Portuguese renal care settings. To advance Renal Psychology practices in Portugal, it is urgent to: (a) enhance the interdisciplinarity of nephrological care by facilitating patient and family access to specialized mental health professionals in dialysis centres; (b) invest in the ongoing training of Clinical Health Psychologists interested in working at the intersection with Nephrology to ensure the provision of disease/treatment‑specific interventions and better respond to the unique assistance needs of this population; (c) build on the evidence of the most (cost)effective, feasible, clinically useful, and acceptable psychological evaluation/support resources in hemodialysis; and (d) expand the use, availability, accessibility, and testing of digital health technologies, such as telepsychology, video-conferencing, and mental health applications, to adapt the structure, scheduling, and duration of psychological assessments and interventions, ensuring that such help is offered at times when those in need are most willing/open to accept them. Renal Psychology is a growing field that presents numerous opportunities and challenges for research, clinical practice, and training in Clinical Health Psychology and Nephrology. The future requires a persistent commitment to design, fund, and disseminate all scientific endeavours and establish fruitful collaborations between researchers and clinicians that will continue to develop and refine evidence‑informed Renal Psychology practices both nationally and internationally.