Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Análise Social

versión impresa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social n.195 Lisboa 2010

Portugal and Spain in the EU: paths of economic divergence (2000-2007)

Sebastián Royo*

*Suffolk University, Beacon Hill, CAS Dean’s Office 41 Temple St. 1st Floor, Boston, MA 02114. e-mail: sroyo@suffolk.edu

This paper examines the integration experiences of Portugal and Spain in the European Union in order to study how it has affected their economic structures and economic performance. It analyzes the relationship between regional integration, economic growth, and economic reforms, draws some lessons based on their EU integration experience, and looks at the impact of European Monetary Union (EMU) integration in the Portuguese and Spanish economies. While the overall benefits of EU/EMU membership are undeniable in both countries, their economic performance diverged starting in 2000. In particular, the paper will examine the reasons for this divergence during the 2000-2007 period. The examination of these cases will show that the process of economic reforms has to be a domestic process led by domestic actors willing to carry them out.

Keywords: Portugal; Spain; European Union; economy.

Portugal e Espanha na União Europeia: caminhos da divergência económica (2000-2007)

Este artigo analisa as experiências de integração de Portugal e de Espanha na União Europeia, estudando as suas consequências ao nível das estruturas e do desempenho económico dos dois países. Examina a relação entre a integração regional, o crescimento económico e as reformas económicas, retira conclusões baseadas nas suas experiências de integração e observa o impacto da união monetária europeia (UME) sobre as economias portuguesa e espanhola. Apesar de os benefícios gerais da integração serem inegáveis para ambos os países, os seus desempenhos económicos revelam divergências desde o ano 2000. Este artigo discute, em particular, as causas desta divergência durante o período de 2000-2007 e procura mostrar que as reformas económicas devem ser empreendidas a um nível nacional por actores empenhados na sua prossecução.

Palavras-chave: Portugal; Espanha; União Europeia; economia.

INTRODUCTION

After decades of relative isolation under authoritarian regimes, the success of processes of democratic transition in Portugal and Spain in the second half of the 1970s paved the way for full membership in the European Community. For Spain, Portugal, and their European Community (EC) partners this momentous and long awaited development had profound consequences and set in motion complex processes of adjustment1.

There was no dispute that the Iberian countries belonged to Europe. This was not just a geographical fact. Spain and Portugal shared their traditions, their culture, their religion, and their intellectual values with the rest of Europe. Moreover, both countries had historically contributed to the Christian occidental conceptualizations of mankind and society dominant in Europe. Without Portugal and Spain the European identity would only be a reflection of an incomplete body. Iberian countries belonged to Europe. Their entry into the European Community was a reaffirmation of that fact, and it would enable both countries to recover their own cultural identity, lost since the Treaty of Utrecht, if not before.

This paper will identify the basic changes in the economies of Portugal and Spain that occurred as a result of European integration, and focus in particular on their economic performance during the 2000-2007 period. Indeed, one of the central paradoxes of the integration of both countries into the European Union and the European Monetary Union (EMU) has been the divergence of their economic performance since 2000. While Spain has experienced some of the fastest rates of growth in the EU between 2000 and 2007, and has already reached the EU per capita average, Portugal, on the contrary, has experienced much lower rates of growth and both nominal and real convergence with the EU have diverged. This paradox has to be explained.

The examination of these two cases will shed new light on the challenges (and opportunities) that countries face when trying to integrate regionally or into the global economy. It will show that countries do respond differently to similar challenges and pressures, and that there is still room for policy choices within a monetary union. These policy choices will affect economic performance.

The paper proceeds in three steps. As historical background information for the paper, I analyze briefly in the first section the overall economic consequences of the EU integration for the Iberian countries. In the second section, I examine the economic performance of Portugal and Spain. The paper closes with an analysis of the reasons for the performance differences between the two countries during the 2000-2007 period.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF EC/EU INTEGRATION2

Economic conditions in Spain and Portugal in the second half of the 1970s and first half of the 1980s were not buoyant. The world crisis caused by the second oil shock in the late 1970s and the lack of adequate response from the collapsing authoritarian regimes in both countries intensified the structural problems of these economies. Portugal had been a founding member of EFTA and had lowered its trade barriers earlier, and was theoretically in a better position than Spain. However, Salazar did even less than Franco to encourage entrepreneurship and competition. This factor combined with the costs of the colonial wars, and the disruptions caused by the revolution and near a decade of political upheaval dramatically worsened the economic situation. For instance, in the 1960s Portugal’s income per capita was about three quarters that of Spain, and in the late 1980s it was only one-half. By the time of accession Spain was the EC’s fifth-largest economy, and Portugal its tenth3.

The economic crisis of the late 1970s and the first half of the 1980s had devastating consequences in both countries and made any additional adjustments caused by the accession to the EC a daunting prospect. The response to the crisis was also influenced by the return to democracy in both countries. The transition period led to a surge in wage demands and industrial unrest, indecisive macroeconomic policies often driven by workers. These were demands that led to expansionary fiscal policies, as well as intense conflict (particularly in Portugal) over the role of the state in the economy.

In Spain the high unemployment levels, which reached 22 percent in 1986, suggested that any additional adjustment cost would have painful consequences (Hine, 1989, p. 7). In addition, the country was unprepared for accession — i. e., Spanish custom duties remained on the average five times higher than the EC’s and EC products faced a major disadvantage in the Spanish market because the country had a compensatory tax system and restrictive administrative practices that more greatly penalized imported products4. Slow license delivery was common, and constructors who sold vehicles in the county did not have import quotas to introduce cars into Spain from abroad. Finally, when Spain and Portugal called at the door of the EC for accession in 1977, protectionist institutions-which were incompatible with EC rules-were still fully operative in both countries. For instance, the Spanish government controlled through the INI (National Institute of Industry) a considerable size of the economy, and subsidized public enterprises such as the auto making companies (SEAT, ENASA), as well as the metallurgic, chemical, ship construction, and electronic sectors. This situation provided a considerable advantage for Spanish manufacturers, which were highly protected from foreign competition.

In this context, EC integration was a catalyst for the final conversion of the Iberian countries into modern Western-type economies. Indeed, one of the key consequences of their entry into Europe has been that membership has facilitated the modernization of the two economies (Tovias, 2002). This is not to say, however, that membership was the only reason for this development. The economic liberalization, trade integration, and modernization of these economies started in the 1950s and 1960s and both countries became increasingly prosperous over the two decades prior to EC accession.

Indeed, the economic impact of the EC started long before accession. The Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) between the EC and Spain (1970) and the EC and Portugal (1972), resulted in the further opening of European markets to the latter countries, which paved the way for a model of development and industrialization that could also be based on exports. The perspective of EC membership acted as an essential motivational factor that influenced the actions of policymakers and businesses in both countries. Henceforth, both countries took unilateral measures in preparation for accession including increasing economic flexibility, industrial restructuring, the adoption of the VAT, and intensifying trade liberalization. Through the European Investment Bank they also received European aid (Spain since 1981) to mitigate some of the expected adjustment costs (for instance on fisheries).

The actual accession of both countries after 1986 had a substantive impact because it forced the political and economic actors to adopt economic policies and business strategies consistent with membership and the acquis communautaire (which included the custom union, the VAT, the common agriculture and fisheries polices, and the external trade agreements; and later the single market, the ERM, and the European Monetary Union). At the same time, EC membership also facilitated the micro- and macroeconomic reforms that successive Iberian governments undertook throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In a context of strong support among Iberian citizens for integration, membership became a facilitating mechanism that allowed the Iberian governments to prioritize economic rather than social modernization and hence, to pursue difficult economic and social policies (i. e., to reform their labor and financial markets), with short-term painful effects. Finally, the decision to comply with the EMU Maastricht Treaty criteria led to the implementation of macro- and microeconomic policies that resulted in fiscal consolidation, central bank independence, and wage moderation.

Nevertheless, the process of EC integration also brought significant costs in terms of economic adjustment, and loss of sovereignty. Under the terms of the accession agreement signed in 1985 both countries had to undertake significant steps to align their legislation on industrial, agricultural, economic, and financial polices to that of the European Community. These accession agreements also established significant transition periods to cushion the negative effects of integration. This meant that both countries had to phase in tariffs and prices, and approve tax changes (including the establishment of a VAT) that the rest of the Community had already put in place. This process also involved, in a second phase, the removal of technical barriers to trade. These requirements brought significant adjustment costs to both economies.

As opposed to the Spanish economy, the Portuguese one was highly open when it joined the EEC (exports and imports represented 75 percent of GDP). As one of the founding members of EFTA, Portugal had liberalized trade in the 1950s and 60s. Therefore, the effects of accession were different: there was trade creation with an increase in bilateral flows with the other member states, as well as a shift effect caused by the diversion of EC exports away from Portugal and toward the EEC countries. At the same time, accession also had an impact on the export structure of the country because the share of labor intensive sectors such as textiles and footwear decreased, while the share of machinery and vehicle supplies increased (by 2000 the latter outweighed the former by 10 percentage points) (Crespo, Fontoura, and Barry, 2004). Finally, it is important to note that EU accession also had different impacts on the economic structures of both countries. For instance, in Portugal it contributed to the devastation of the primary sector and the deindustrialization of the country, while in Spain those effects were somewhat more mitigated. Indeed, new studies have shown how patterns of trade have fundamental different effects on patterns of production and employment (Saeger, 1996).

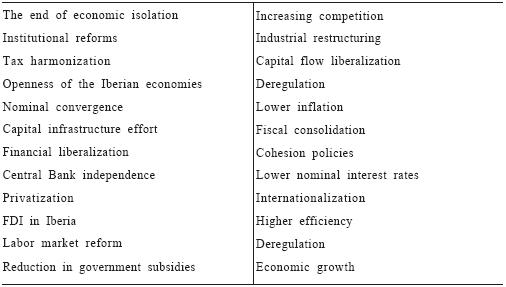

Since 1986 the Portuguese and Spanish economies have undergone profound economic changes. EU membership has led to policy and institutional reforms in the following economic areas: monetary and exchange rate policies (first independent coordination, followed by accession to the ERM, and finally EMU membership); reform of the tax system (i. e., the introduction of the VAT, and reduction of import duties); and a fiscal consolidation process. These changes have led to deep processes of structural reforms aimed at macroeconomic stability and the strengthening of competitiveness of the productive sector. On the supply side, these reforms sought the development of well-functioning capital markets, the promotion of efficiency in public services, and the enhancement of flexibility in the labor market. As a result, markets and prices for a number of goods and services have been deregulated and liberalized; the labor market has been the subject of limited deregulatory reforms; a privatization program was started in the early 1980s to roll back the presence of the government in the economies of both countries and to increase the overall efficiency of the system; and competition policy was adapted to EU regulations. In sum, from an economic standpoint the combined impetuses of European integration and economic modernization have resulted in the following outcomes:

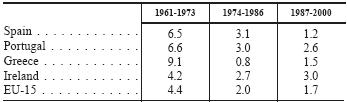

The iberian economic transformation

[TABLE 1]

At the same time, however, for the Iberian manufacturers accession to the Community has also resulted in more competition. Since Portuguese and Spanish nominal tariffs averaged 10-20 percent before EC entry, and generally speaking manufacturing EC products were cheaper and more competitive, membership resulted in an increase of imports from the EC and therefore, in a worsening in the balance of current account (and the closure of many industrial enterprises in Iberia). The intensity of the adjustment, however, was mitigated by the behavior of exchange rates and by the dramatic increase in the levels of investment in these two countries. Spain and Portugal have been attractive production bases since they both offered access to a large market of 48 million people, and a well educated and cheap labour base, compared with the EC standards. In the end, the transitional periods adopted in the treaty to alleviate these adjustment problems and the financial support received from the EC played a very important role minimizing the costs for the sectors involved.

At the time of accession, it was considered that a critical factor determining the final outcome of integration would be the pattern of investment, which would bring about important dynamic effects. Spain and Portugal had a number of attractive features as a production base including; good infrastructure, educated and cheap labor force, and access to markets with a growing potential. In addition, EC entry would add the incentive of further access to the EC countries for non-EC Iberian investors — i. e., Japan or the US. As expected, one of the key outcomes of integration was a dramatic increase in foreign direct investment, from less than 2 percent to more than 6 percent of GDP over the last decade. This development was the result of the following processes: economic integration, larger potential growth, lower exchange rate risk, lower economic uncertainty, and institutional reforms. EC membership has also resulted in more tourism (which has become one of the main sources of income for Spain).

Another significant dynamic effect has been the strengthening of Iberian firms’ competitive position. As a result of enlargement, Iberian producers gained access to the European market, which provided additional incentives for investment and allowed for the development of economies of scale, resulting in increasing competitiveness. By the 1980s Spain and Portugal were already facing increasing competition for their main exports (clothing, textiles, leather) from countries in the Far East and Latin America, which produced all these goods at cheaper costs, exploiting their low wages. As a result of this development, the latter countries where attracting foreign investment in sectors were traditionally Portugal and Spain had been favored. This situation convinced the Iberian leaders that their countries had to shift toward more capital-intensive industries requiring greater skills in the labor force but relying on standard technology — e. g., chemicals, vehicles, steel and metal manufacturers. In this regard, Portugal and Spain’s entry to the EC facilitated this shift. Both countries gained access to the EC market, thus attracting investment that would help build these new industries. Finally, Portugal and Spain also benefited from the EC financial assistance programs — i. e., the European Regional Development Fund, the Social Fund, the Agriculture Guidance and Guarantee Fund, and the newly created Integrated Mediterranean Program for agriculture, and later on from the cohesion funds.

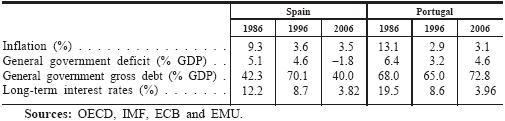

EC integration has also allowed both economies to become integrated internationally and to modernize, thus securing convergence in nominal terms with Europe. One of the major gains of financial liberalization, the significant decline in real interest rates, permitted Portugal and Spain to meet the Maastricht convergence criteria. Indeed on January 1st, 1999 Spain and Portugal became founding members of the European Monetary Union. In the end, both countries, which as late as 1997 were considered outside candidates for joining the Eurozone, fulfilled the inflation, interest rates, debt, exchange rate, and public deficit requirements established by the Maastricht Treaty. This development confirmed the nominal convergence of both countries with the rest of the EU.

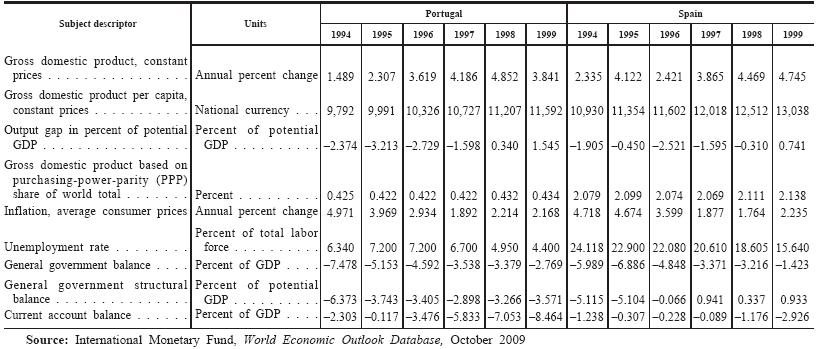

Compliance of the EMU convergence criteria (1996-2006)

[TABLE 2]

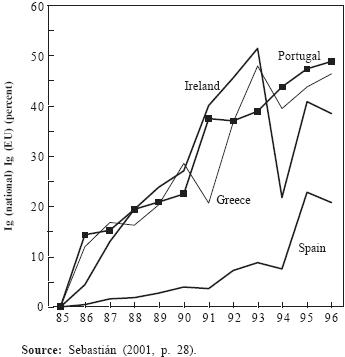

The EU contributed significantly to this development. Article 2 of the Treaty of Rome established that the common market would “promote throughout the Community a harmonious development of economic activities” and therefore lower disparities among regions. While regional disparities among the original EC members were not striking (with the exception of Southern Italy), successive enlargements increased regional disparities with regard to per capita income, employment, education, productivity, and infrastructure. Regional differences led to a north-south divide, which motivated the development of EC structural policies. The election of Jacques Delors in 1985 as president of the Commission led to renewed efforts to address these imbalances. They culminated in the establishment of new cohesion policies that were embodied in the 1986 Single European Act, which introduced new provisions making economic and social cohesion a new EU common policy. In this regard, the regional development policy emerged as an instrument of solidarity between some Europeans and others. Since the late 1980s the structural funds have become the second largest EU budgetary item. These funds have had a significant impact in relationship to the investment needs of poorer EU countries and have made an impressive contribution to growth in aggregate demand in these countries.

Indeed, the structural and cohesion funds have been the instruments designed by the EU to develop social and cohesion policy within the European Union, in order to compensate for the efforts that countries with the lowest per capita income relative to the EU (Ireland, Greece, Portugal, and Spain) would need to make in order to comply with the nominal convergence criteria. These funds, which amount to just over one-third of the EU budget, have contributed significantly to reducing regional disparities and fostering convergence within the EU. As a result, major infrastructure shortcomings have been addressed and road and telecommunication networks have improved dramatically both in quantity and quality. In addition, increased spending on education and training have contributed to the upgrading of the labor force. In sum, these funds have played a prominent role in developing the factors that improve the competitiveness and determine the potential growth of the least developed regions of both countries (Sebastián, 2001).

During the 1994-1999 period, EU aid accounted for 1.5 percent of GDP in Spain and 3.3 percent in Portugal. EU funding has allowed rates of public investment to remain relatively stable since the mid-1980s. The percentage of public investment financed by EU funds has been rising since 1985, to reach average values of 42 percent for Portugal, and 15 percent for Spain. Moreover, the European Commission has estimated that the impact of EU structural funds on GDP growth and employment has been significant. Indeed, Spain has benefited extensively from European funds: approximately 150 bn Euros from agricultural, regional development, training, and cohesion programs. In the absence of these funds public investment would have been greatly affected.

Percentage of public sector investment financed with EU funds

[FIGURE 1]

The combined impetuses of lowered trade barriers, the introduction of the VAT, the suppression of import tariffs, the adoption of economic policy rules (such as quality standards, or the harmonization of indirect taxes), and the increasing mobility of goods and factors of production that comes with greater economic integration, have boosted trade and enhanced the openness of the Portuguese and Spanish economies. Since 1999, this development has been nurtured by the lower transaction cost and greater exchange rate stability associated with the single currency. For instance, imports of goods and services in real terms as a proportion of GDP rose sharply in Spain (to 13.6 percent in 1987 from 9.6 percent in 1984), while the share of exports shrank slightly (to 15.8 percent of GDP from 16.6 percent in 1984, and from 17.1 percent of real GDP in 1992 to 27 percent in 1997). As a result, the degree of openness of the Portuguese and Spanish economies increased sharply over the last two decades. Henceforth, changes to the production structure and in the structure of exports, indicators of the degree of competitiveness of the Portuguese and Spanish economies (i. e., in terms of human capital skills, stock of capital, technological capital) show important improvements, although significant differences remain in comparison to the leading developed economies (which confirms the need to press ahead with the structural reforms). These achievements verify that in terms of economic stability, Spain and Portugal are part of Europe’s rich club.

THE PARADOX OF DIVERGENCE

REAL CONVERGENCE

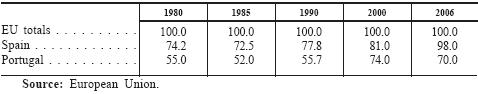

Yet, while nominal convergence has largely taken place, the income levels of Portugal and Spain have increased at a much slower pace and for Portugal in particular they remain far behind the EU average:

Percent GDP per capita performance (1980-2006)

[TABLE 3]

Percent annual growth in real GDP per person employed (1995 prices)

[TABLE 4]

The data from tables 2, 3, and 4 show that nominal convergence has advanced at a faster pace than real convergence. Indeed, 24 years have not been long enough. Portugal’s and Spain’s European integration reveal both convergence and divergence, nominal and real. Since 1997 inflation in Spain has exceeded the EU average every year. In Portugal real convergence has been slowing down each year since 1998, actually turning negative in 2000 and with both real and nominal divergence decreasing until 2006.

While there is significant controversy over the definition of real convergence, most scholars agree that a per capita GDP is a valid reference to measure the living standards of a country. This variable, however, has experienced a cyclical evolution in the Iberian countries with significant increases during periods of economic expansion and sharp decreases during economic recessions. For instance, in the first 15 years from the adhesion of Spain to the EU in 1986, per capita income increased “only” 11.5 percent and Portugal’s 14.2 percent. Ireland’s, in contrast, increased 38 percent. Only Greece, with an increase of 6.8 percent, had a lower real convergence than Spain and Portugal.

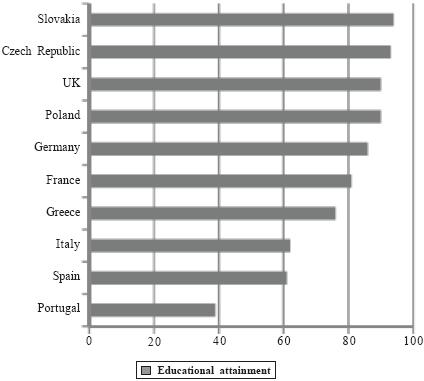

A possible explanation for this development is the fact that while Spain grew between 1990 and 1998 an average of 2.1 percent, Portugal grew 2.5 percent, and Ireland 7.3 percent over the same period. This growth differential explains the divergences in real convergence. In the mid-1990s other explanations include: the higher level of unemployment (15.4 percent in Spain in the mid-1990s); the low rate of labor participation (i. e., active population over total population, which stands at 50 percent, which means that expanding the Spanish labor participation rate to the EU average would increase per capita income to 98.2 percent of the EU average); the inadequate education of the labor force (i. e., only 28 percent of the Spanish potential labor force has at least a high school diploma, in contrast with the EU average of 56 percent); low investment in R&D and information technology (the lowest in the EU, with Spain ranked 61, spending even less proportionally than many developing countries, including Vietnam) (World Economic Forum, 2003); and inadequate infrastructures (i. e., road mile per 1000 inhabitants in Spain is 47 percent of the EU average and railroads 73 percent). The inadequate structure of the labor market with high dismissal costs, a relatively centralized collective bargaining system, and a system of unemployment benefits that guarantees income instead of encouraging job search, have also hindered the convergence process5.

More remarkable in light of this more recent divergence is the fact that the performance of both economies was quite similar during the first 13 years that followed their accession to the EU.

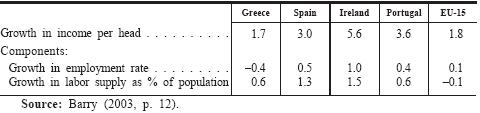

Components of growth in income per capita (1987-2000)

[TABLE 5]

Indeed, between 1994 and 2000 the growth in income per capita was of 3.1 percent in Spain and 3.1 percent in Portugal. Yet since then, instead of catching up, Portugal has been falling behind with GDP per capita decreasing from 80 percent of the EU25 average (without Bulgaria and Romania) in 1999 to just over 70 percent in 2006; and labor productivity, still at 40 percent of the EU average, has shown no growth since 2000. Portugal’s per capita GDP has fallen far behind Spain, and since 2000, the Czech Republic, Greece, Malta, and Slovenia have all surpassed Portugal’s. Moreover, Portugal was the first member of the European Monetary Union to be threatened with sanctions by the European Commission under the Growth and Stability pact (GSA) for violating the excessive deficit provisions. The country became, in the word of the Economist, “the new sick man of Europe”.

We will examine next the performance of both countries during the 1999-2008 period.

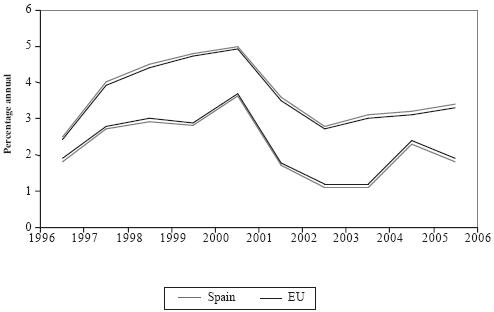

SPAIN

Before the global crisis that hit Spain in the spring of 2008, which has had devastating consequences for the Spanish economy, the country had become one of Europe’s (until then) most successful economies6. While other European countries had been stuck in the mud, Spain performed much better at reforming its welfare systems and labor markets, as well as at improving flexibility and lowering unemployment. Indeed, over the last decade and a half the Spanish economy has been able to break with the historical pattern of boom and bust, and the country’s economic performance was nothing short of remarkable. Aided by low interest rates and immigration, Spain was (in 2008) in its fourteenth year of uninterrupted growth and it was benefiting from the longest cycle of continuing expansion of the Spanish economy in modern history (only Ireland in the Euro zone has a better record), which contributed to the narrowing of per capita GDP with the EU7. Indeed, in 20 years per capita income grew 20 points, one point per year, to reach close to 90 percent of the EU-15 average. With the EU-25 Spain has already reached the average. The country has grown on average 1.4 percentage points more than the EU since 1996 (see figure 2).

GDP growth in Spain

[FIGURE 2]

Unemployment fell from 20 percent in the mid-1990s to 7.95 percent in the first half of 2007 (the lowest level since 1978), as Spain became the second country in the EU (after Germany with a much larger economy) creating the most jobs (an average of 600,000 per year over the last decade)8. In 2006 the Spanish economy grew a spectacular 3.9 percent and 3.8 percent in 2007. As we have seen, economic growth contributed to per capita income growth and employment. Indeed, the performance of the labor market was spectacular: between 1997 and 2007, 33 percent of all the total employment created in the EU-15 was created in Spain. In 2006 the active population increased by 3.5 percent, the highest in the EU (led by new immigrants and the incorporation of women in the labor market, which increased from 59 percent in 1995 to 72 percent in 2006); and 772,000 new jobs were created. The public deficit was also eliminated (the country had a superavit between 2005-2006, which reached 1.8 percent of GDP, or 18 bn Euros, in 2006), and the public debt was reduced to 39.8 percent of GDP, the lowest in the last two decades9. The construction boom has also been remarkable: more than 400,000 new homes were built in and around Madrid between 2002-2007.

The overall effects of EMU integration were also very positive for the country: it contributed to macroeconomic stability, it imposed fiscal discipline and central bank independence, and it dramatically lowered the cost of capital. One of the key benefits was the dramatic reduction in short-term and long-term nominal interest rates: from 13.3 percent and 11.7 percent in 1992, to 3.0 percent and 4.7 percent in 1999, and 2.2 percent and 3.4 percent in 200510. The lower costs of capital led to an important surge in investment from families (in housing and consumer goods) and businesses (in employment and capital goods). Without the Euro the huge trade deficit that exploded in the second half of the 2000s would have forced a devaluation of the peseta and the implementation of more restrictive fiscal policies.

The economic success extended to Spanish companies, which now expanded beyond their traditional frontiers (Guillén, 2005). In 2006 they spent a total of 140 bn Euros ($184 bn) on domestic and overseas acquisitions, putting the country third behind the United Kingdom and France11. Of this, 80 bn Euros were to buy companies abroad (compared with the 65bn Euros spent by German companies)12. In 2006 Spanish FDI abroad increased 113 percent, reaching 71,487 bn Euros (or the equivalent of 7.3 percent of GDP, compared with 3.7 percent in 2005)13. In 2006 Iberdrola, an electricity supplier purchased Scottish Power for $22.5 bn to create Europe’s third largest utility; Banco Santander, Spain’s largest bank, purchased Britain’s Abbey National Bank for $24 bn, Ferrovial, a family construction group, concluded a takeover of the British BAA (which operates the three main airports of the United Kingdom) for 10bn pounds; and Telefonica bought O2, the U. K. mobile phone company14. Indeed, 2006 was a banner year for Spanish firms: 72 percent of them increased their production and 75.1 percent their profits, 55.4 percent hired new employees, and 77.6 percent increased their investments15.

The country’s transformation was not only economic but also social. Spaniards have become more optimistic and self-confident (i. e., a Harris poll showed that they were more confident of their economic future than their European and American counterparts, and a poll by the Center for Sociological Analysis showed that 80 percent are satisfied or very satisfied with their economic situation)16. Spain is “different” again and according to a recent poll it has become the most popular country to work for Europeans17. Between 2000-2007, some 5 million immigrants (645,000 in 2004 and 500,000 in 2006) settled in Spain (8.7 percent of the population compared with 3.7 percent in the EU-15), making the country the biggest recipient of immigrants in the EU (they represent 10 percent of the contributors to the Social Security system). This is a radical departure for a country that used to be a net exporter of people, and more so because it has been able to absorb these immigrants without falling prey (at least so far) to the social tensions that have plagued other European countries (although there have been isolated incidents of racial violence) (Calativa, 2005)18. Several factors have contributed to this development19. First, economic growth, with its accompanying job creation, provided jobs for the newcomers while pushing down overall unemployment. Second, cultural factors: about one-third of the immigrants come from Latin America, and they share the same language and part of the culture, which facilitates their integration. Third, demographic: an ageing population and low birthrates. Finally, the national temperament characterized by a generally tolerant attitude, marked by the memory of a history of emigration, which make the Spanish more sympathetic to immigrants (according to a recent poll no fewer than 42 percent state that migration has had a positive effect on the economy). The proportion of children from mixed marriages increased from 1.8 percent in 1995 to 11.5 percent in 200520.

These immigrants contributed significantly to the economic success of the country in that decade because they boosted the aggregate performance of the economy: They raised the supply of labor, increased demand as they spent money, moderated wages, and put downward pressure on inflation, boosted output, allowed the labor market to avoid labor shortages, contributed to consumption, and increased more flexibility in the economy with their mobility and willingness to take low-paid jobs in sectors such as construction and agriculture, in which the Spanish were no longer interested21.

Indeed, an important factor in the per capita convergence surge after 2000 was the substantive revision of the Spanish GDP data as a result of changes in the National Accounts from 1995 to 2000. These changes represented an increase in GPD per capita of 4 percent in real terms (the equivalent of Slovakia’s GDP). This dramatic change was the result of the significant growth of the Spanish population since 1998 as a result of the surge in immigration (for instance in 2003 population grew 2.1 percent). The key factor in this acceleration of convergence, given the negative behavior of productivity (if productivity had grown at the EU average Spain would have surpassed in 2007 the EU per capita average by 3 points), was the important increase in the participation rate, which was the result of the reduction in unemployment, and the increase in the activity rate (proportion of people of working age who have a job or are actively seeking one) that followed the incorporation of female workers into the labor market and immigration growth. Indeed between 2000 and 2004 the immigration population multiplied by threefold.

The determinants of real convergence in Spain (2000-2004)

(UE-25 = 100)

[TABLE 6]

As a matter of fact most of the 772,000 new jobs created in Spain in 2006 went to immigrants (about 60 percent)22. Their motivation to work hard also opened the way for productivity improvements (which in 2006 experienced the largest increase since 1997, with a 0.8 percent hike). It is estimated that the contribution of immigrants to GDP in the last four years has been of 0.8 percentage points23. Immigration has represented more than 50 percent of employment growth, and 78.6 percent of the demographic growth (as a result Spain led the demographic growth of the European countries between 1995 and 2005 with a demographic advance of 10.7 percent compared with the EU-15 average of 4.8 percent)24. They have also contributed to the huge increase in employment, which has been one of the key reasons for the impressive economic expansion. Indeed, between 1988 and 2006, employment contributed 3 percentage points to the 3.5 percent annual rise in Spain’s potential GDP (see table 7)25.

However, this economic success was marred by some glaring deficiencies that came to the fore in 2008 when the global financial crisis hit the country, because it was largely a “miracle” based on bricks and mortar (Martinez-Mongay and Maza Lasierra, 2009; Martinez-Mongay, 2008)26. The foundations of economic growth were fragile because the country has low productivity growth (productivity contributed only 0.5 percentage points to potential GDP between 1998 and 2006) and deteriorating external competitiveness27. Over the last decade Spain did not address its fundamental challenge, its declining productivity, which has only grown an average of 0.3 percent in the last 10 years (0.7 percent in 2006), one whole point below the EU average, placing Spain at the bottom of the EU and ahead of only Italy and Greece (the productivity of a Spanish worker is the equivalent of 75 percent of a U. S. one). The most productive activities (energy, industry, and financial services) contribute only 11 percent of GDP growth28.

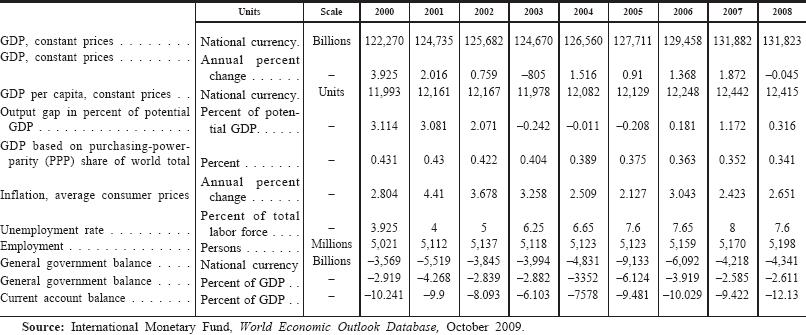

Economic summary Spain (2000-2008)

[TABLE 7]

Moreover, growth was largely based on low-intensity economic sectors, such as services and construction, which are not exposed to international competition. In 2006 most of the new jobs were created in low-productivity sectors such as construction (33 percent), services associated with housing such as sales and rentals (15 percent), and tourism and domestic service (30 percent). These sectors represent 75 percent of all the new jobs created in Spain in 2006 (new manufacturing jobs, in contrast, represented only 5 percent). The temporary labor rate reached 33.3 percent in 2007, and inflation is a recurrent problem (it closed 2006 with a 2.7 percent increase, but the average for that year was 3.6 percent), thus the inflation differential with the EU (almost 1 point) has not decreased, which reduces the competitiveness of Spanish products abroad (and consequently Spanish companies are losing market share abroad)29.

In addition, family indebtedness reached a record 115 percent of disposable income in 2006, and the construction and housing sectors accounted for 18.5 percent of GDP (twice the Eurozone average). House prices have risen by 150 percent since 1998, and the average price of a square meter of residential property went up from 700 Euros in 1997 to 2,000 at the end of 2006, even though the housing stock had doubled. Many wonder whether this bubble is sustainable30. The crisis that started in 2008 confirmed the worst fears.

Between 40 and 60 percent of the benefits of the largest Spanish companies came from abroad. Yet, in the last few years this figure has decreased by approximately 10 percentage points, and there has been a decline in direct foreign investment of all types in the country, falling from a peak of 38.3 bn Euros in 2000 to 16.6 bn Euros in 200531. The current account deficit reached 8.9 percent of GDP in 2006 and over 10 percent in 2007, which makes Spain the country with the largest deficit in absolute terms (86,026 mn Euros), behind only the United States; imports are 25 percent higher than exports and Spanish companies are losing market share in the world. And the prospects are not very bright. The trade deficit reached 9.5 percent in 200832.

While there is overall consensus that the country needs to improve its education system and invest in research and development to lift productivity, as well as modernize the public sector, and make the labor market more stable (i. e., reduce the temporary rate) and flexible, the government has not taken the necessary actions to address these problems. Spain spends only half of what the Organization of European Co-operation and Development (OECD) spends on average on education; it lags most of Europe on investment in research and development (R&D); and it is ranked 29th by the UNCTAD as an attractive location for research and development. Finally, other observers note that Spain is failing to do more to integrate its immigrant population, and social divisions are beginning to emerge (see Calavita, 2005)33.

By the summer of 2008 the effects of the crisis were very evident, and since then the country has suffered one of the worst recessions in history, with unemployment reaching over 18 percent at the end of 2009, and more than 4.2 mn people unemployed. This collapse was not fully unexpected. The global liquidity crisis caused by the subprime, and the surge in commodities, food, and energy prices brought to the fore the unbalances in the Spanish economy: the record current account deficit, unabating inflation, low productivity growth, dwindling competitiveness, increasing unitary labor costs, excess consumption, and low savings, had all set the ground for the current devastating economic crisis (see Royo, 2009).

PORTUGAL

Portugal’s economic performance was also remarkable in the 1990s. Between 1994 and 2000 real GDP growth, export-led but also boosted by private consumption and fixed investment, averaged more than 3 percent annually and economic expansion continued for seven years. In 1996, the fifth year of expansion, GDP growth reached almost 4 percent, and in 2000 3.25 percent. The unemployment rate also fell, reaching a record low of around 4 percent in 2000 (one of the lowest in Europe), and inflation was brought down to just over 2 percent in 1999. Portugal was also able to meet the Maastricht criteria for fiscal deficit following the consolidation efforts prior to 1997, which brought the deficit down to 2.5 percent of GDP. One of the important factors that contributed to this performance was the transformation of the financial sector, largely spurred by EU directives in interest rate deregulation, liberalization of the regulatory framework, privatization, and freeing of international capital movements (OECD, 1999, 13). The privatization program, one of the most ambitious in Europe at the time (more than 100 firms were sold), was also a contributing factor because it increased competition and enhanced productivity gains, and generated revenues that averaged more than 2 percent of GDP per year.

Macroeconomic performance: Portugal and Spain (1994-1999)

[TABLE 8]

The performance of the labor market was also very satisfactory, particularly compared with Spain (see table 8). Real wage flexibility facilitated labor market adjustments, and access to atypical forms of employment, such as self-employment, made it possible to circumvent rigid regulations. In addition, regulatory reforms and new policy initiatives contributed to improve education and training; modified the legal regime governing redundancies, and reduced the compensations that companies have to pay to dismiss workers; changed the unemployment benefit system to avoid the unemployment “trap”, and the social security contributions for self-employed were brought into line with those for employees (OECD, 1999, 16-17). A high degree of wage flexibility, active employment policies, and the increasing use of more flexible forms of employment, such as fixed-term contracts, were all credited for the low unemployment (4.0 percent in 2000, down from 7.3 percent in 1996) and relatively high employment rates (the participation rate was 71.3 percent by 2000). Moreover, the concertation policies of the 1990s contributed to social peace and wage moderation. For instance, in the Social Pact of 1996 management and labor reached binding commitments that facilitated reforms and wage restraint (Royo, 2002). Yet, the economic boom pushed wages up, and since 1999 there was increasing wage drift, which hindered competitiveness.

However, starting in 1998 this performance started to deteriorate. The disinflation process was halted and inflation increased 2.8 percent by the end of that year fueled by inflation and the Expo 98; and the trade deficit deteriorated from 5.4 percent of GDP in 1997 to 6.6 percent in 1999. The harmonized CPI reached over 4 percent in early 2001, above the EU average, pushed by higher oil prices and a weaker Euro. Furthermore, economic growth also started to slow, dragged down by the ending of major infrastructure projects and Expo 98. The outset of EMU membership led to a progressive easing of monetary conditions and a sharp decline of interest rates. This happened, however, at a time of high consumer demand in which domestic credit was also booming and the current account deficit was widening (it remained at around 10 percent of GDP up to 2002). Access to EMU in 1999 did not alleviate the situation because Portugal was in a more advanced position in the cycle than the other EMU member states (the country was experiencing a credit boom and signs of overheating were starting to emerge), but now monetary policy was in the hands of the European central bank, and it was making decisions based on developments in the entire EMU area, hence the cut in interest rates in April of 1999 (OECD, 1999, 10-11). Indeed, there was a change of conditions after the ECB started to gradually raise rates from November 1999 on.

Furthermore, the end of the decade, which coincided with the country’s accession to EMU (e. g., the pressure to fulfill the Maastricht criteria was no longer a powerful incentive), also witnessed a slowdown in the fiscal consolidation efforts, which had led to the successful reduction of the fiscal deficit between 1994 and 1997 (there was an annual reduction of almost 1.2 percentage points, and the deficit was reduced to 2.5 percent by 1997). Yet, about half of this fiscal adjustment was the result of the reduction of the public debt burden facilitated by the lower interest rates and non-recurring receipts (such as the sale of mobile concessions in 2000). As a matter of fact, the primary surplus increased half a point per year between 1994 and 1997. On the contrary, there was no increase of taxes, or increases in revenues as the result of improvements in the collection of taxes or social security contributions. Moreover, current expenditures on education, health, and social protection increased steadily (OECD 1999, 11). This pro-cyclical policy stance did not bode well for the subsequent slowdown of the economy because Portugal was left with little fiscal leeway to apply counter-cyclical measures once the crisis hit. In order to improve the margin of maneuver, Portugal should have reduced the weight of the public sector and also implemented structural reforms to check the growth of current expenditures, which would have allowed for a reduction in tax pressure. The country would have needed a significant surplus to ensure balance for the budget over the cycle, but unfortunately this did not happen.

Indeed, in the context of EMU, fiscal policy was the main instrument available to the government to dampen demand pressures and bring the current account deficit (8 percent of GDP in 2002) and inflation (over 3.8 percent) down. Yet, while the general government deficit continued to decline in accordance with the Stability and Growth pact (SGP), and fell below 3 percent of GDP in 2000, the pace of fiscal consolidation was slow and the gains from lower debt payments and higher revenues were used to increase primary current spending. Given the inflationary pressures and the advanced stage of the economic cycle, fiscal consolidation would have helped to control demand pressures. Increasing taxes was not an attractive option because, although the overall tax burden (at 34 percent in 2000) was comparatively low, it would have been difficult politically, and also it risked eroding the export-oriented growth and harming the country’s competitive position. Therefore, in order to meet budget deficit targets, the government became accustomed to implementing spending freezes. But it failed to address the structural causes of spending overruns: the public sector payroll bill (spending per employee had been growing rapidly due to high wage increases and pension benefits); and pressures in the social security system caused by population ageing. On the contrary, it continued to rely on increases in current revenue, as opposed to significant progress in spending control, and when these did not materialize, it adopted contingency measures to reduce expenditures, which showed fundamental weaknesses in the budget process (OECD, 2001, p. 12). This would prove to be a major Achilles heel for the sustainability of economic growth.

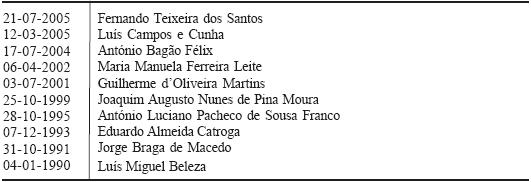

In the end, economic performance started to deteriorate markedly after 2000. Real GDP growth averaged less than 1 percent between 2000 and 2005 (in 2003 the economy contracted 0.8 percent), and annual growth remained fragile until 2006. In 2005 the Portuguese economy grew a meager 0.91 percent of GDP, and in 2006 1.3 percent as a result of the depression of demand (consumption is one of Portugal’s important pillars of economic growth but it grew only 2.3 percent in 2004, 2.1 percent in 2005, and 1.1 percent in 2006), and in particular of private demand given the few incentives on consumption (it grew 0.2 percent in 2004, decreased 3 percent in 2005, and grew only 0.8 percent in 2006); as well as investment, which was pushed down as a consequence of the restrictions on public spending and the increase of taxes to bring down the deficit. The accumulated output gap since the recession was one of the largest in the euro area, and productivity growth in the business sector fell to around 1 percent between 2004-05 (it was 3 percent in the 1990s). Unemployment also increased sharply, reaching 7.6 percent in 2005 and 8 percent in 2007, the highest rate in 20 years (it was only 3.8 percent in 2000) (IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2009).

The recession was far longer and more intense than anyone anticipated, with a dramatic impact on the government accounts: the fiscal deficit reached unsustainably high levels (see table 9), pushed by the bill from organizing the European Championship Cup in 2004, which left no room to stimulate demand and thereby contributed to the length of the crisis. The government attempted to reduce the fiscal deficit by raising indirect taxes and establishing emergency spending cuts or freezes, and one-off decisions, such as measures to control the wage bill over the short-term. However, while these measures helped to reduce the deficit in the short-term (and it was brought down to 2.8 percent in 2003), they proved insufficient because of the lower revenues at a time of a depressed economic environment (it went up again to 6.1 percent in 2005). Portugal had violated the SGP during several years (see table 9), as it had remained above the maximum 3 percent deficit established by the SGP, and therefore it was submitted to the excessive deficit procedure, which further hindered confidence and dampened expectations. Public debt also deteriorated: it grew from 53 percent of GDP in 2000, to 65.9 percent in 2005, and decreased to 60 percent in 2006; as well as fixed capital formation, which fell 2.9 percent in 2005, 0.7 percent in 2006 and grew 2.8 percent in 2007. The country also suffered a decline in investment and savings. The investment rate fell from a peak of 28.1 percent of GDP in 2000 to 20.6 percent in 2006, while the gross savings rate fell from 17 percent in 2000 to a pale 12.3 percent in 2006, bouncing back a bit in 2007 to 15.1 percent (OECD, 2006).

Economic summary Portugal (2000-2008)

[TABLE 9]

In the end, the reliance on one-off measures, however, did not address the structural reasons for the deficit, and also reduced the necessary sense of urgency to tackle structural reforms. For instance, once the deficit was below 3 percent, the government decided to lower taxes rapidly, despite the fact that the situation had not improved much. Three of the fundamental challenges were: first, the reform of the civil servants pension system and the need to bring it into line with the general pension system (the system was under strong pressure from the ageing population, and also by the high replacement rates granted to pensioners: it was estimated that lack of action would bring the system into deficit by 2007); second, the reform of the health system; finally, the reform of the public administration to align legal condition of employment, and remuneration with the private sector, and restructure the central administration (OECD, 2006).

The victory of the Socialist Party in the 2005 election brought in a new government committed to implementing the structural reforms needed to bring the deficit below 3 percent by 2008. Indeed, the new government pushed for important structural reforms and implemented tough decisions. Upon taking office in March 2005, Prime Minister Sócrates announced the immediate increase of the value added tax by 2 percent, breaking his electoral commitment not to increase taxes, in order to cope with the budget deficit. Moreover, in the face of strident opposition from labor unions and organized interests, his government pushed for the reform of the public sector and the civil servants, and an extensive restructuring of Portugal’s state bureaucracy, increasing the retirement age to 65 years and eliminating traditional benefits such as vacations, automatic promotions, and corporative medical insurance. One of the main goals of this reform according to Fernando Teixeira dos Santos, Finance Minister, was that “from now on, governments will be able to run the public administration in accordance with the demands of public management and not, as it has been in the past, the other way around”34.

The government also approved a comprehensive pension reform plan in the summer of 2005, which sought to address the combined threat of a sharp decline in birth rates, which had fallen 35 percent over the last 30 years (from 2.6 to 1.5), and increased longevity (people over 65 years old are forecast to comprise more than 32 percent of the population in 2050, compared to 17 percent in 2005). As a result, the pension system posed a serious structural challenge: Portugal has 1.7 million pensioners, 1.1 million of which receive less than 375 Euros per month, but pensions in Portugal were in 2006 among the most generous in the European Union, often reaching more than 100 percent of an employee’s final salary, and the system was expected to face financial collapse by 2015. It was estimated that pension expenditures would grow from 5.5 percent of GDP in 2006 to 9.6 percent by 2050. Based on this reform workers have the choice of working longer or increasing their pension contributions, and includes a “sustainability co-efficient” that will be used to adjust pensions according to life expectancy during the working life of contributions (for instance, it would decrease pension about 5 percent if the life expectancy were to increase by one year over the next decade). At the same time, in order to increase Portugal’s birth rate, the reform also establishes a new system under which pension contributions are calculated as a percentage of earnings according to the number of children employees have: contributions would remain unchanged for employees with two children, decrease if they have more than 2, and increase if they have less. Finally, the system establishes a radical change in the way pensions are calculated: before the reform only the 10 best years of the last 15 years of an employee’s working life were taken into account to calculate the pension, after the reform the pension would be calculated using the whole working life of the contributors. According to some estimates, as a result of these reforms, most pensions are expected to be reduced by at least 10 percent for people retiring over the next 20 years and will hit high earners the hardest. These reforms, which came into force in 2006, are expected to guarantee the sustainability of the system up to 2050 and beyond35.

The Sócrates government also carried through an ambitious privatization plan that sought to raise 2.4 bn Euros from the sale of public enterprises between 2006-2009, including the three leading public energy groups (GALP, EDP, and REN), the paper sector (Portucel Tejo, Portucel, and Inapa); as well as the Portuguese flag airline company (TAP) and the national airport company (ANA). This was quite exceptional coming from a Socialist government, especially in light of the long-standing opposition to the privatization of companies that have been declared “untouchable” for years. The aim of this decision was to reduce the public deficit and the role of the state in the economy, which in 2006 still had direct participation in 150 companies.

Education reform has also been high on the agenda. Education attainment is a huge problem in Portugal and its low level has hindered competitiveness and productivity (see below). The government decided that “it cannot wait for the next generation to replace the current workforce” in the words of Prime Minister Sócrates, and therefore it tried to provide education and training for people currently at work, with the aim “to have a million more employees with an educational level equivalent to full secondary schooling”. In order to achieve this goal, the government introduced a new program called “New Opportunities” that seeks to encourage adults to complete their secondary education. It also provides vocational training for youngsters. The initial results were very encouraging: it attracted 250,000 applicants within three months of its launch in early 200736.

The government also tried to counter the opposition to these reforms with an ambitious infrastructure plan that would have cost over 50 bn Euros (only 8 percent from public funds, the rest will be from private funding and mixed concessions), and included the construction of new airports (Lisbon, Alcochete); the building of new dams (one of the cornerstones of the government’s energy policy to reduce oil dependency) and highways (there are 11 new tenders); new high speed trains (AVE Porto-Lisbon, and Lisbon-Madrid which also involves a new bridge over the Tagus river); as well as other projects in the private sector, such as a new refinery in Sines (4 bn Euros); a Volkswagen manufacturing plant in Palmela to produce the VW models Siroco and Eos (750 mn); new tourist resorts in Melides (510 mn) and Tróia (500 mn); a new paper plant in Figueira da Foz (500 mn); a new furniture plant and new Ikea shops (350 mn), and a new Corte Ingles commercial center in Gaia (150 mn), which are expected to generate billions of Euros in investment and employment. The most ambitious proposal, however, is the Technological Plan to advance the EU Lisbon Agenda in Knowledge, Technology, and Innovation. The government is committed to installing broadband in all Portuguese schools, and has signed an innovative agreement with MIT37, and another one with Bill Gates to facilitate the learning of computing to one million Portuguese38.

In the end the combination of fiscal consolidation (the ratio of public spending to GDP fell from an excessive 47.7 percent of GDP in 2005 to 45 percent in 2008), structural reforms, and increasing revenues from stronger economic growth have all helped Portugal to bring the deficit back under control: The Sócrates government, which inherited a deficit of 6.8 percent of GDP from the previous administration, has been able to bring its budget deficit below the maximum limit allowed by the EU a year ahead of schedule, after achieving a larger cut than forecast in 2006. The deficit fell to 3.9 percent of GDP in 2006, 0.7 percentage points lower than the 4.6 percent target agreed with the European Commission as part of the plan to avoid the sanctions hanging over the country for breaching the SGP. In 2007, one year ahead of schedule, the deficit fell to 2.5 percent, below 3 percent (well down from the initial goal of 3.7 percent) and the lowest level since 2000. More importantly this reduction was achieved not only through ad hoc cuts, although the government had to apply severe cuts in public spending and investment, but largely through structural reforms and a sharp increase in tax revenues (after the government recruited a private sector banker to spearhead the crackdown on tax evasion), which will make it easier to consolidate the gains.

The government was also relatively successful in its attempt to bring down inflation, which decreased from 4.41 percent in 2001, to 2.1 percent in 2005 (but it grew to 3 percent in 2006). Other economic indicators also improved markedly: exports (which represent 20 percent of GDP) increased 8.9 percent in 2006 and 6.2 percent in 2007, and 5.6 percent in 2008; fixed capital formation also increased 2.5 percent in 2007 (it fell 1.6 percent in 2006); as well as consumption, which grew 1.5 percent in 2007. Unemployment, however, is still a challenge: despite the creation of more than 100,000 jobs since 2005, it rose from 6.25 percent in 2003 to 7.65 percent in 2006, and the unemployment rate more than doubled between 2000 and 2007 (from less than 3.9 percent to 8 percent). Finally, stronger economic growth resumed: in 2006, the economy grew 1.3 percent, and in 2007 1.8 percent, the highest rate in six years. This sudden and unexpected turnaround since 2006 took many economists by surprise. Yet, growth was negative again in 2008 at –0.045 percent, led by the effects of the global economic crisis, which have forced the government to adopt new measures to address it, including the so-called Robin Hood Tax an exceptional tax of 25 percent for the oil companies to fund social expenditures39, and the reduction of taxes (the IRS) for housing purposes for the population in the lower tax brackets, as well as a modification of the maximum rates of the municipal real estate taxes40.

REASONS FOR THE IBERIAN ECONOMIC DIVERGENCE BETWEEN 2000-2007

DOMESTIC FISCAL POLICIES

Lax monetary policies had played a significant role in the slowdown of the convergence process prior to EC accession (Barry, 2003). However, since Spain and Portugal became founding members of EMU, monetary policies were no longer in the hands of their national governments, and therefore cannot help to account for differences in performance between the two countries. However, different fiscal policies, within the constraints imposed by the Growth and Stability Pact, have played a central role. It is now widely accepted that increases in government consumption adversely affect long-term growth, and also that while fiscal consolidation may have short-term costs in terms of activity, they can be minimized if consolidation is credible, by implementing consistent decisions that deliver solid results.

Both the Portuguese and Spanish economies experienced a boom in the second half of the 1990s, boosted by the considerable fall in interest rates, when nominal short-term interest rates converged to those set by the ECB. In both countries, they fell more rapidly than did inflation, and the simultaneous processes of financial liberalization and increasing competition that took place at the same time, which contributed to increasing domestic demand, and in particular housing demand, further boosted their impact. The expansion in these years was driven largely by internal demand. This boom coincided with a period of international expansion. This growth, however, would have required a concomitant prudent fiscal policy, which in the case of Portugal did not take place. On the contrary, the cyclically adjusted primary balance fell from 1.2 percent of GDP in 1994-1996 to –0.6 percent in 1999-2001. At the same time, the combination of expansionary fiscal policies and insufficient structural reforms did not prepare the country for the economic downturn.

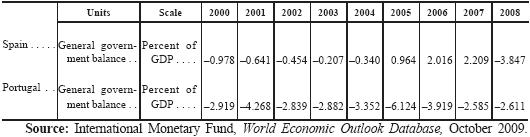

Indeed, as we have seen in the previous section, one of the fundamental reasons for the poor performance of the Portuguese economy between 1999 and 2006 was the lack of fiscal discipline and the failure in the adoption of ad hoc measures to control the deficit. Spain, on the contrary, was one of the most disciplined countries in Europe (even in the world) and was able to maintain a margin of maneuver that allowed fiscal policy to be used in a counter-cyclical way (see table 10).

General government balance, Portugal and Spain (2000-2007)

[TABLE 10]

Indeed, there is widespread consensus that Portugal’s biggest mistake was its “chronic fiscal misbehavior”41. Vítor Constâncio, Governor of the Bank of Portugal, has acknowledged that “when in 2001 we had these big shocks to growth, tax revenues dropped and suddenly we were in a situation of an excessive deficit… The sudden emergence of budget problems led to a big revision of expectations about the future”42. As we have seen, largely as a result of this revision of expectations, the Portuguese economy contracted by 0.8 percent in 2003. The deficit reduction, on the contrary is credited by Fernando Teixeira dos Santos, Finance Minister, with restoring “Portugal’s credibility in international markets and strengthen[ing] confidence in the economy”43. The improvement in the financial position of the budget allowed the government to cut the value added tax from 21 to 20 percent in July 2008 to stimulate the economy. Fiscal consolidation and structural reforms were expected to allow more robust growth and place Portugal in a better position to face the current global crisis caused by the US subprime crisis and international crunch, as well as the high prices of energy and commodities. As a result, the Portuguese experience shows that countries wishing to join the Eurozone need to have a “comfortable budget position because that will give for maneuver once inside”44. Not surprisingly, of the cohesion countries, the ones that have done better in the last decade and a half have been those who have maintained fiscal discipline: Ireland and Spain, which have either maintained a budget surplus or reduced their budget deficits to comply with the SGP, while reducing their total expenditures vis-à-vis GDP. Portugal, as we have seen, was the exception.

EMU ACCESSION

The experiences of Portugal and Spain within EMU show that there have been lasting performance differences across countries. These differences can be explained at least in part by a lack of responsiveness of prices and wages, which have not adjusted smoothly across sectors, and which in the case of Portugal and Spain has led to accumulated competitiveness loses and large external imbalances.

The economic downturn coincided with Portugal’s accession to the European Monetary Union, and the adoption of the Euro in 2002. EMU, however, cannot be blamed for the poor performance of the Portuguese economy. If that was the culprit, it would be hard to explain how the other cohesion countries have performed much better. Yet, it is important to note that there was a significant difference in the conversion rate of the peseta and the escudo vis-à-vis the euro, which further hampered Portugal’s competitiveness (Soares, 2008, p. 5). When the national currencies were fixed to the Euro at the end of 1998, the Spanish peseta was converted at a rate of 166 pesetas to one Euro, and the Portuguese Escudo was fixed at 200 escudos. Yet, in the years previous to the final conversion of exchange rates there had been a significant devaluation of the peseta vis-à-vis the Euro: it had devalued about 30 percent, while the escudo had devalued only 12 percent (in the early 1990s the exchange rate was 128 pesetas for one Euro, and 179 escudos to one Euro, respectively). In other words, the fixed exchange rate at which Spain joined EMU was significantly more favorable than Portugal’s. This problem was compounded by the appreciation of the real effective exchange rate in the 1990s due to wage increases: while it depreciated by approximately 15 percent in Spain, in Portugal it appreciated by the same amount. According to the European Commission, the Portuguese real effective exchange rate is approximately 20 percent higher than it was in the early 1990s (while Spain’s is at the same level) (European Commission 2008, pp. 111-113). This is an important consideration when trying to account for the loss of competitiveness of Portugal vis-à-vis Spain.

Both countries provide interesting insights into the pitfalls of integration into a monetary union. As noted by Vítor Constâncio, Governor of the Bank of Portugal, one of the main lessons from Portugal’s experience is that “countries used previously to high inflation and high interest rates are likely to experience an explosion in consumer spending and borrowing” upon joining the monetary union. This spurt will make a downturn inevitable, particularly in cases such as Portugal, which are vulnerable to higher oil prices and increasing competition from developing countries like India and China. In Portugal and Spain the strong demand stemmed from the sharp fall in interest rates, but in Portugal it was further fueled by expansive fiscal policies. Demand, however, was not followed in either country by a parallel increase in supply, as it was hindered by low productivity growth, which led to a significant increase in imports and high external deficits and debts. External indebtedness in turn has led to lower available income domestically.

This is a potential lesson for future EMU applicants: lower interest rates and the loosening of credit will likely lead to a credit boom that may increase housing demand and household indebtedness. This boom will lead to higher wage increases, caused by the tightening of the labor market, and losses in external competitiveness, together with a shift from the tradable to the non-tradable sector of the economy (Abreu, 2006, 5). In Spain the tightening of fiscal policies prevented the consequent bust, even though, in the end, the global crisis that started in 2008 also exposed the imbalances of the Spanish economy.

LABOR MARKET POLICIES

While this paper has emphasized the relative underperformance of Portugal’s economy in terms of real convergence, it is important to highlight that Portugal has a much better employment record than Spain’s. Labor market rigidities are seen to have played an important role in accounting for the Spanish labor market performance throughout the 1980s and 1990s. On the contrary, Portugal has had a remarkably successful employment record, which has been the object of important work by scholars such as Robert Fishman, Oliver Blanchard, Juan F. Jimeno, Pedro Portugal, José da Silva Lopes, Gosta Esping-Andersen, David Cameron, and others. According to Fishman (2004) there are three main reasons associated with the legacies of Portugal’s democratic transition in the 1970s: the high level of female participation rate; the availability of credit to small companies; and finally, the “nature of the Portuguese welfare state which became increasingly ‘employment-friendly’ in the 1990s”.

As we have seen, Spain introduced far-reaching reforms in the 1990s which have contributed to bringing down the highest unemployment rate in the EU. Still, in Spain a central concern has been the so-called “safeguard clauses” included in labor agreements, which allow for the indexation of wages if inflation increases over the government’s forecast for the year (which is used as the basis for the agreement). A consequence of these clauses has been the increase in unitary labor costs, which has hindered Spain’s competitiveness. The other main problem is job instability: as we have seen temporary rates standing at over 30 percent, the highest in the OECD, which also dampens competitiveness (Royo, 2008).

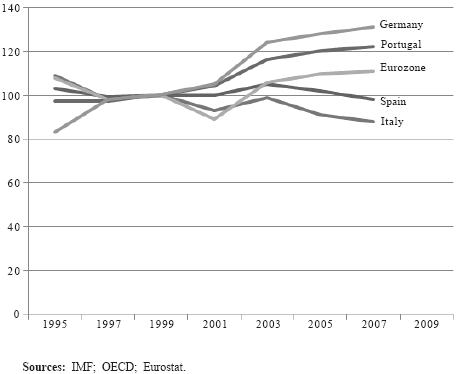

Indeed, while Germany (and other EMU countries) implemented supply-side reforms to bring labor costs down, through wage restraint, payroll tax cuts, and productivity increases (making it the most competitive economy with labor costs 13 percent below the Eurozone average), Portugal and Spain continued with the tradition of indexing wage increases to domestic inflation rather than the European Central Bank target, and they became the most expensive ones: Portugal with labor costs 23.5 percent above average and Spain 16 percent (followed by Greece with 14 percent and Italy with 5 percent)45.

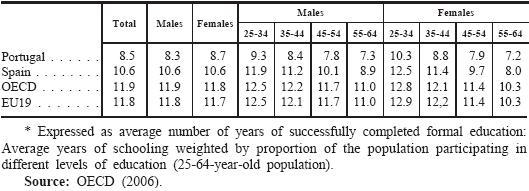

POLICY STABILITY

One of the key differences between the two countries is that in Spain there has been remarkable economic policy stability following the crisis of 1992-1993. There were few economic policy shifts throughout the 1990s and first half of the 2000s, and this despite changes in government. Between 1993 and 2008 there were only two Ministers of Finance, Pedro Solbes (from 1993-1996, and from 2004-2008) and Rodrigo Rato (from 1996-2004)46; and the country had only two Prime Ministers (José María Aznar, and José Luís Rodríguez Zapatero)47. More importantly, each of the last three governments has completed its mandate and there have been no early elections. In addition, as a rare occurrence, Pedro Solbes, who was Minister of Finance under a Socialist government in the early 1990s when the process of fiscal consolidation started, became Minister of Finance again in 2004 after the Socialist Party won the general election and he is still in that same position. The power of the Minister of Finance was also reinforced vis-à-vis the other cabinet members because both of them also served as deputies of the Prime Minister in the government under the Conservative and Socialist administrations. This pattern was further reinforced by the ideological cohesiveness of these parties and the strong control that party leaders exercise over all the members of the cabinet and parliament deputies.

In addition, this stability was bolstered by the shared (and rare) agreement among the Conservatives and Socialist leaders regarding fiscal consolidation (the balanced budget objective was established by law by the Popular Party), as well as the need to stand firm in the application of conservative fiscal policies and the achievement of budgetary fiscal surpluses. Indeed, this happened to such a degree that Spain became the paradigmatic model of a country applying the budget surplus policy mantra. The Aznar government repeatedly chastised other European governments that were far laxer in their fiscal policies, to the point that it created tensions with the richer EU countries, because although they were in fact running higher deficits, they were net contributors to the EU budget and provided Spain with cohesion and structural funds (i. e., Germany and France). Unsurprisingly, it was hard for them to accept being called irresponsible and to have fingers pointed at them while they were subsidizing Spain through the European solidarity programs.

This dogmatism, however, worked well in the short term and contributed to the credibility of the government policies. In the medium and long terms, however, there are disputes about whether a more accommodating policy would have been positive to upgrade the productive base of the country with investments in necessary infrastructure and human capital. The maintenance of the balanced deficit paradigm as a goal on its own, may have blinded the governments to the benefits of investing in new technology areas in which Spain is still lagging behind. This may have contributed to a faster change in the model of growth and may have reduced the dependency on the construction sector, which is now in the midst of a sharp recession that is having devastating consequences for the Spanish economy.

In Portugal, however, there have been more changes at the prime minister level (there were four PMs between 1995 and 2005) and the previous three prime ministers resigned before their terms were over for different reasons. António Guterres was PM between October 28, 1995 and April 6, 2002. During his first term Portugal enjoyed a solid economic expansion and staged very successfully the Expo 98. The beginning of the economic crisis and the Hintze Ribeiro disaster, in which 70 people died when the bridge collapsed damaging his popularity, however, marred his second term. He resigned following the disastrous result for the Socialist party in the 2002 local elections, stating that “I will resign to prevent the country from falling into a political swamp”. Following a general election won by the opposition Social Democratic Party, the Social Democrat party leader José Manuel Durão Barroso became PM on April 6, 2002. He held the post through July 17, 2004, governing in coalition with the People’s Party. He resigned when he was named President of the European Commission (at a time when the Portuguese economy was entering one of the worst phases of the economic crisis, which was very criticized). Pedro Miguel Santana Lopes replaced him from his own party, and held the position between 29 June 2004 and 12 March 2005. His short tenure was marred by controversies over his unusual election (he was not elected by popular vote), the fact that he was not a member of parliament (he was Mayor of Lisbon when he was selected PM), and continuous PR fiascos, which led President Sampaio to dissolve Parliament and call for early elections. Finally, the Socialist José Sócrates, who won the general election in a landslide victory with an overwhelming absolute majority (45 percent of the vote and 121 seats) for the first time since the democratic transition, became PM in 2005 and he is still in that position (re-elected in September of 2009). These constant changes up to 2005 made economic policy continuity more problematic and more importantly, made the implementation of reforms in the face of popular opposition very difficult.

Furthermore, the minister of finance position became a revolving door, bringing instability to the economic policy portfolio, with ministers often resigning in protest for their inability to hold sway over their colleagues and control fiscal policies and expenditures. Between 1990 and 2005 there were ten ministers of finance, and on average they have been less than two years in the position. The problem was compounded, as opposed to Spain, by the finance minister’s limited powers over the budget. Indeed, according to a recent study (Halleberg et al., 2004) of all the EU-15 finance ministers the Portuguese one has the lowest control over the formulation, approval, and implementation of the budget.

Minister of Finance, Portugal (1990-2008)

[TABLE 11]