Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social n.197 Lisboa 2010

Competitiveness and cohesion: urban government and governances strains of Italian cities**

Francesca Governa*

* Dipartimento Interateneo Território, Politecnico e Università di Torino, Viale Mattioli 39, 10124 Torino, Italy. e-mail: francesca.governa@polito.it

This article discusses current limitations and opportunities in Italian urban governance. Since the 1990s Italy has been going through changes concerning its political and institutional system. The changes in the roles and organisation of the State and more generally for the public actors, recognisably affects urban governments. Italian urban policies are therefore called upon to deal with the introduction of inter-institutional forms of cooperation between various levels of government; co-ordination between a multiplicity of actors and interests; involvement of private sector institutions; and the direct participation of citizens in the decision making processes. Much less clear is whether and how the debate around the different dimensions of urban governance has gained real influence including in the governance practices of cities and in the capacity of policies to address urban problems.

Keywords: Italy; EU policy; planning; urban regeneration policies.

Competitividade e coesão: tensões no governo e na governança das cidades italianas

Neste artigo reflecte-se sobre as actuais limitações e oportunidades na governança urbana em Itália. Desde a década de 90 do século xx que a Itália tem assistido a mudanças nos seus sistemas político e institucional. As mudanças no papel e na organização do Estado, e mais globalmente nos agentes públicos, afectam reconhecidamente os governos urbanos. As políticas urbanas são, portanto, campo muito relevante na introdução de formas inter-institucionais de cooperação entre vários níveis de governo; coordenação entre uma multiplicidade de actores e de interesses; envolvimento de instituições do sector privado e participação directa dos cidadãos nos processos de tomada de decisão. Muito menos claro é o debate sobre as dimensões que ganharam real influência nas práticas de governança e na qualidade das políticas para enfrentar as questões urbanas.

Palavras-chave: Itália; políticas europeias; políticas de regeneração urbana.

Introduction

Changes of the organisational forms and modes of action of the Nation-State give rise to two simultaneous levels of redefinition: the redefinition of the national territory as a stable framework of reference and belonging and the redefinition of the role of the State as a political entity in charge of regulation and redistribution (Cassese, 2001). According to Jessop (1994), these processes involve, at least partially, a hollowing-out of the Nation-State with the consequent re-articulation of powers and responsibilities toward supra- and infra-national institutional levels (e.g. European Union and local authorities) and toward horizontal networks of power, acting independently of the institutional processes of functions and competencies decentralisation. Changes of roles and functions do not occur separately from spatial changes: the redefinition of State functions is accompanied, and simultaneously intensified, by the re-scaling of State territoriality (Brenner, 1999, 2004). Therefore, supra- and infra-national territories are called upon to play a new economic, social, symbolic, and political role, with the consequent multiplication of spatial subdivisions and of the stages for policies and interventions; a diversification of scales within which collective actions attain their relevance; and a proliferation of conflicts of both representation and power (Vanier, 1999; Debarbieux and Vanier, 2002). The change in the territorial organisation of the State thus intersects with the transformation of its roles and of the forms of national statehood (Rhodes, 2000). The focus on these aspects overcomes a conception of the State as mere container of organized hierarchical power, highlighting the problem of transversal interaction and coordination between different levels of territorial organisations and of the political and institutional action (Brenner, 2000).

However, albeit spatially reconfigured, Nation-State institutions do not passively undergo such processes, but engage in them as actors in their own right. In this sense they continue to play a key role in the political and economic restructuration at all geographical levels, as well as to formulate, implement, coordinate, and supervise policies. The redefinition of both the institutional levels and the areas in which political and institutional actions shape themselves has not generated a unidirectional process on a single scale be it European, regional, or local is replacing the national scale as the primary level of political and economic coordination (Brenner, 2004, p. 3). New modes of public action thus define a shift in the meaning of the role of the State and they do not represent evidence of its decline, overcoming the poor and in many ways controversial dichotomous opposition between government and governance. Indeed, the distinction between these two models is not entirely clear, and refers to a continuum of intersecting aspects and features of both government and governance. From this perspective, the emergence of governance should [...] not be taken as proof of the decline of the state but rather of the states ability to adapt to external changes. Indeed [...] governance as it emerged during the 1990s could be seen as institutional responses to rapid changes in the states environment (Pierre, 2000b, p. 3).

Within this framework, the article will present and discuss the characteristic of the Italian urban governance, from both the conceptual and the empirical point of view, with the aim of showing its limitations and opportunities. Since the 1990s, Italy has been going through a period of intense change concerning its political and institutional system. As in other European countries more or less during the same period, the beginning of the decentralisation processes has led to a reshaping of the relationships between the State and the local governments, establishing a new framework of competences and defining new models for the public-actor action (Cammelli, 2007). The change of the organisation and the role of the State (and more generally of the public actor) also affects a change of urban government, spreading the (ambiguous, problematic, and often purely rhetorical) term of urban governance (Balducci, 2000; Bolocan Goldstein, 2000; Perulli, 2004; Palermo, 2009)1. Italian urban policies are therefore called upon to deal with the introduction of inter-institutional forms of cooperation between various levels of government; of co-ordination between a multiplicity of actors and interests; of involvement of private sector institutions; and of direct participation of citizens in the decision making processes. Reading urban policy documents prepared by various Italian cities during this period reveals a clear change in the objectives and forms of the public action. Much less clear is whether, and how, the debate surrounding the different dimensions of the urban governance has gained real influence even in the governance practices of cities and in the capacity of policies to address urban problems.

The article is structured as follows: after setting out all the legislative and institutional changes that form the framework of the existing urban policies in Italy, we will present the main plans and programmes of urban governance, to discuss then some critical nodes of the Italian experience. These nodes refer to the emergence of a change which is rather more said than done, characterised by inertias against innovation, the resurfacing of old problems, and the difficult balancing between patterns of public action seeking, at least theoretically, to hold together the needs for economic development and the well being of the population.

The Italy of the 1990s: decentralisation process and institutional changes for the urban government

The plot of the relationships amongst the processes of political and institutional decentralisation, and the redefinition of the relationships between the State, the local authorities, and the urban and spatial policies may be identified by focusing on the forms and the modality of cities government, beginning with the identification of the modification introduced by the new tools of urban and spatial planning. Gathering the different aspects of innovation is not an easy task. Innovation is indeed often only superficial: frequently ending in the spreading of new slogans which conceal very traditional behavioural styles concerning the operative modus of the public administration and of the major economic and social actors (Pasqui, 2008). Moreover, innovation does not always directly improve the state of things; facets of innovation are mixed with the preservation of old organisational structures and the inevitable inertia that lurks in the processes of design and implementation of policies (Governa, 2004). Finally, new instruments do not always correspond to new governance practices from public administrations, neither to different modes of urban action, nor to more efficient and effective outcomes of urban issues (Palermo, 2009).

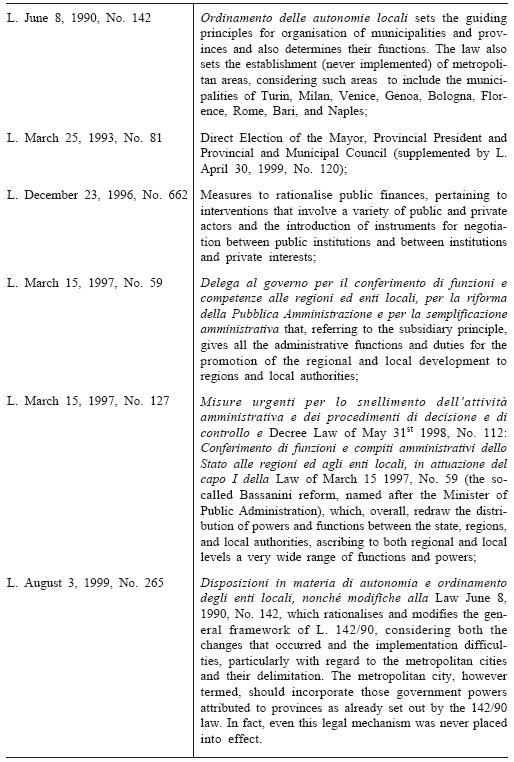

Despite these limitations, there is evidence of the path followed by the changes that have occurred in the context of Italian urban policies. They correspond to the main innovations in legislation that trigger changes in urban governance practices (Vandelli, 2000; Camelli, 2007) (Table 1).

Major national laws for the reorganisation of functions and responsibilities between State, regions, and local authorities

[table 1]

The movements toward decentralisation and the progressive local government reform date back to the mid-1980s, with a gradual acceleration in the early 1990s, at a time of deep crisis in the Italian political and institutional system. Measures taken gain the form of an attempt to radically change the institutional arrangements, reforming the systems of control and distribution of responsibilities and power between State and local authorities. The attempt was to simplify the administrative interventions and boost public administration efficiency. The principles from which these laws take inspiration fit in with the trend toward the progressive decentralisation of administrative and political action, which concerns (at roughly the same time) all European countries (Governa, Janin Rivolin and Santangelo, 2009). Such principles seem to envisage, at least in general terms, the redesign of the relationship between State, local authorities, and civil society following an entirely different approach from the traditionally institutional arrangements of the western world, which B. Dente (1999) summarised in the formula of the riduzione amministrativa della complessità (administrative reduction of complexity), namely of razionalizzazione via accentramento e riduzione dei conflitti attraverso la loro sussunzione a livello superiore (rationalisation through centralisation, and reduction of conflicts by their subsumption at higher level) (p. 113).

This phase ended (not only symbolically) with the amendment of the Italian Republic Constitution of 1948. Such change, implemented through the constitutional law No. 1 of 1999 and No. 3 of 2001 and the subsequent confirmative referendum of October 7, 2001, covers nine Constitution Articles, contained in Title V, concerning the territorial ruling of the State. Basically, the modification of Title V sought to establish the foundations and preconditions for a future transformation of Italy into a federal republic based on the principles of vertical subsidiarity between different levels of government and horizontal subsidiarity between public authorities and citizens, and on principles of legislative, administrative, and fiscal federalism. To the State are reserved essentially exclusive legislative powers only in certain fields (such as foreign policy and international relations, immigration, defence, and security), while issues of governo del territorio (territorial government), of economic and production development, of scientific and technological research, of transport and communications, and of cultural and environmental valorisation are matters of legislative competence shared with the regional level. The administrative functions, even concerning specific matters reserved to the national level in terms of legislation, are allocated across the various levels of government according to an ascending criterion (often termed as vertical subsidiarity), which favours the local level and, in primis, the municipalities. Article 114 also details that the Italian Republic is formed of municipalities, provinces, metropolitan cities, regions, and the State. In this sense, all are autonomous entities with their own respective statutes, powers, and functions according to the principles fixed by the Constitution. Thus the metropolitan cities, although being an administrative level never implemented in Italy despite a constant recall of its necessity for roughly two decades, extend beyond the ordinary legal framework to enter directly into the Constitution, thereby becoming necessary and not only possible institutions.

The reforms that led to a progressive increase in the administrative and institutional competences of regions and local authorities, beginning with the administrative decentralisation and the reform of the Constitutions Title V, however, were not accompanied by any simultaneous process of recognition of autonomy and financial accountability at the local level. In parallel, the transfer of central powers and functions to municipalities and the need for the local public administration to contain services costs, while still preserving their quality and maintaining the essential functions of government, have led to the introduction of new forms of local public service management. In this context, market forms or mixed forms of quasi market in the management of local public services has emerged, also through the adoption of private sector working methods and organisation by the public sector. In particular, the increase in the outsourcing of most local public services, firstly those related to economic and then also the one related with human beings, has progressively weakened the political and technical role of local authorities. Therefore, within this context the reference to models of governance has been basically translated into the adoption of the principles of the minimal state (Rhodes, 2000)2. Overall, the time lag between the devolution of functions, competences, and resources and the gradual retreat of the role of public bodies in the delivery of public services have led to the revival of a centre/periphery model in the relationship between the State and local authorities, which is clearly expressed in the fiscal sides of the federalist proposals enacted into law in May 2009. In practice, the central government, more than just retaining regulatory powers, the ability to propose interventions and the determinant resources for their implementation, also maintains a strong influence both on the side of revenues and real taxation, and in terms of the spending and its relative functions. The local level, on the other hand, appears paradoxically undermined from both the legal and financial perspective, and operates within the narrow channel between the sharing of central powers and attempts to defend its own options.

In addition to the change in the legal and institutional framework, with all the aforementioned problems and difficulties, the construction of the framework of Italian urban governance has also been influenced by the role played by the European Union (EU)3. Initiatives and community programmes have indeed spread in the Italian practices the core principles and the current European urban policys mainstream (Janin Rivolin, 2003; Gualini, 2004). In particular, the 1999 ESDP (European Spatial Development Perspective), Interreg and Urban initiatives, the regional policy and procedures for managing structural funds, and the Territorial agenda of May 2007 have together gradually changed, in different but converging manners, the Italian public administration mode of action. It might be enough to consider, as an example, the revolution introduced in the Italian practices by the widespread adoption of the competitive procedure for the allocation of financial resources, with the consequential diffusion of evaluation procedures and rewarding mechanisms (Ferrero, 2004). At the same time, local authority autonomy, subsidiarity, accountability, appropriateness of the public structures to the carrying out of the responsibilities assigned to them, flexibility in inter-institutional relationships, citizen participation in collective choices, and streamlining the bureaucracy, i.e. the key principles of EU policy approach (Janin Rivolin, 2003), became, even in Italy, the cardinal points that structure urban policies.

The relevance of this set of changes, beyond declarations of intent, should obviously be tested in practice in order to assess whether and how they affected the attitudes and styles of the public administrations government, and whether they had any practical modalities on the transformation and development of the Italian cities.

The change in the practices: projects and programmes of urban governance

Institutional and legislative changes translate into a variety of policies, plans, and interventions of different origins and natures, which have changed the government of Italian cities, spreading forms of urban governance rapidly, although often only superficially. Amongst the many projects and plans that have changed and continue to change the way in which Italian cities are managed and governed, main examples of the characteristics assumed by Italian urban governance are the strategic plans, whose overriding goal is to promote the urban competitiveness in the global arena, and the so-called complex programmes, aimed at urban regeneration. The reference to the dimensions of governance (from horizontal and vertical subsidiarity to citizens participation, from the territorialisation of policies to the changing role of public entities, see Davoudi et al., 2009), seems particularly evident, at least in intentions, in these two areas of urban government. However, many of the transformations that have taken place in Italian cities in recent years, and their forms of government, are often the result of decisions, actions, and policies made outside of the governance framework. These include sectoral policies, in particular those relating to public transportation and mobility; changes in the local service management systems, with a rising hollowing-out of the political and technical role of municipalities; the implementation of administrative decentralisation, with the progressive increase of the powers of Regions and local authorities, accompanied by a steady reduction in the transfer of financial resources and the continuing lack of recognition of financial independence. These are all examples of processes which have deeply affected Italian cities, outside of any coherent framework and without there having ever been any systematic effort to interpret the impact of the various aspects on urban governance4.

Within the programmes that explicitly refer to the term of governance, the examples given by the strategic planning, as emerging from the not so many critical reflections on the Italian experience (see Perulli, 2004; Palermo, 2009), enable us to detect a specific trend of the urban governance in Italy. Italian strategic plans fit into a conception of urban governance outlining the city governments ability to successfully confront the diversity and fragmentation of actors and interests that act in the decision-making arena to promote competitiveness and economic development. The assumption underlying this interpretation is that the city can be interpreted and managed as a collective actor (Bagnasco and Le Galès, 1997; Le Galès, 2002). Hence, the strategic plan becomes a tool that assumes and expresses the formation of the citys collective actor. The aim is to define a shared vision of the urban future within which are manifested and integrated the interests of a number of actors and social groups, in order to define the positioning strategies of the city toward the market, the State, and other cities considered to be, according to the dominant rhetoric, benchmarks (see Conti, 2002).

In Italy strategic planning was established in the mid-1990s, relatively late compared with other European countries (Barcelona, considered a beacon for the Italian strategic plans, began this in 1988). The first Italian city to adopt a strategic plan was Turin in 2000, with a plan subsequently revised and updated in 2006 (Torino Internazionale, 2000 and 2006). However, Italian cities have recovered quite quickly from the slow start of strategic planning processes. The strategic plan of Turin was quickly followed by the experiences of La Spezia, Florence, Cagliari, Asti, Bari, Bolzano, Carbonia, Jesi, Prato, Venice, Naples, and others. Hence, the model of strategic planning, thanks also to the funding set up by the Ministry of Infrastructures and Transport, spreads throughout the country, from north to south, and in cities of varying sizes and with different development opportunities and issues. Many Italian cities have turned to the strategic plan as a tool to address problems posed by the crisis of the old industrial model and by the need to promote the local economy and employment, especially so in the light of the progressive decline in the redistributive capacities of the central state.

Obviously, it is difficult to make an overall assessment of the strategic plans of the various Italian cities, as each represents a special case. However, reflecting again on the more general trends than on the individual cases, it is still possible to identify the main strengths and weaknesses that characterise the Italian strategic planning experience. The major factor of interest is the reference to a strategic dimension of the urban government, which points to a change of Italian practices long centred on a strictly technical view of planning5. The strategic content of the urban government puts at the heart of the planning process the comparison with the political and social dynamics of cities, the power relationships present within them, and the supra-local flows and relationships in which cities are included. Meanwhile, the Italian strategic plans are often configured around a joint set of generic objectives, as purely rhetorical statements unable to express an effective capacity for action, or even as documents that promote, rather than the elusive citys collective actor, the development strategy expressed by the dominant urban regimes and coalitions of interest. The Italian strategic plans are therefore frequently constructed as a set of goals entirely alien to the project of physical transformation of the city, thanks to the failure of relationship between the definition of strategies and the operative choices of urban planning, and also to the (often) lack in the direct mobilisation of responsibilities by the actors involved in the project implementation. Conversely, when strategic choices rely physically on big urban projects, relating to the transformation of significant sections of the urban fabric, the strategic plans are crushed under the interests of ruling elites and, in particular, under those with interests in the building and construction sectors, ending mainly in mere real estate operations.

The role of urban regimes and coalitions of interest that govern cities is not, of course, a novelty. It might be sufficient to take into consideration the wide international literature on the city as a growth machine and on the urban regime (Molotch, 1976; Logan and Molotch, 1987; Stoker and Mossberger, 1994; Mossberger and Stoker, 2001; Lauria, 1996; Dowding, 2001; Stone, 2005). What is surprising in the Italian case is that the strategic plans are often only vague attempts to assert the existence of an aggregate dimension of interests and that, even more frequently, it is difficult to perceive the presence of different strategic visions of urban government. In essence, what emerges from the Italian strategic plans is the difficulty of the urban elites to fully express their interests and to make coalitions, to mobilise the necessary resources toward urban development, and to direct strategic choices toward a new spatial order (Mazza, 2000). Even the strategic plan of Turin, for a long time listed as a virtuous example of the Italian strategic plans, had been more recently subject to a critical interpretation that emphasised its rhetorical and highly ornamental dimensions (Palermo, 2009; on Turins coalitions of interest, and their difficulties, see Belligni, Ravazza and Salerno, 2009).

The second set of projects where it is possible to find traces of urban governance in Italy are the so called complex urban programmes, which constitute the Italian way to urban regeneration (Governa and Saccomani, 2004). These programmes, which have often been implemented in accordance with EU Urban initiative or through projects emulating its spirit, have disseminated urban governance practices based on the integration principle, inter-sectoral approach, and methodologies of participation of inhabitants.

The complex urban programmes have had a widespread deployment and have been used as a means of intervention for urban regeneration in many Italian cities of varying sizes and importance from both the economic and territorial perspective. In addition to regional capitals, which have witnessed the problems of exclusion and marginalisation typical of major cities (Milan, Turin, Rome, Naples, Palermo), experiences of urban regeneration have also been implemented in small towns (Cosenza, Foggia, Livorno, Rovigo, Salerno, Savona, Syracuse) or in smaller municipalities, often located in suburban areas near large cities (Seregno and Cinisello Balsamo, near Milan, or Settimo Torinese and Venaria Reale, near Turin).

It is difficult to determine the results actually achieved by such programmes because they are locally very different. However, despite the obvious differences, some elements characterise all Italian urban regeneration practices (Governa and Saccomani, 2004).

The complex urban programmes have changed the way in which urban regeneration was established in Italian cities, traditionally focused on physical interventions. The role of communitarian urban initiative, or the inspiration from its guide-principles, allowed channelling measures into relatively small areas within cities to integrate social, environmental, and economic initiatives and to spread methods and techniques for the direct participation of citizens in decision making processes. In this sense, urban governance in Italy has experienced various forms of integration between sector and policies, partnerships, building, definition of financial frameworks, as well as less bureaucratic relations with urban planning instruments and legislation.

There are also critical issues. In the Italian complex programmes, inequalities and the difficulties encountered by the cities are deemed local problems requiring local solutions. This approach is based on a specific approach to describe and interpret the city (see, for a critical view, Amin and Thrift, 2002): the city is seen and conceptualised as a defined and static space, somehow impermeable to external flows and relations. Through forms of local mobilisation, interventions implemented in complex urban programmes seek to promote the social mixité or to improve the built environment of neighbourhoods but do not try to fight the supra-local sources of injustice. Hence the ratio of complex urban programmes seems to fit perfectly with the celebration of the local (Governa, 2008), which are based on, and together determined by, the a priori assumption that local actions are preferable to others, in relation to the supposed or real capability of the local level to develop projects and strategies that are more effective, democratic, sustainable, and right (Purcell, 2006).

The issues of integration and participation, which are those of great potential innovation in recent international experiences of urban regeneration (for example, Parkinson, 1998; Atkinson, 2000; Chorianopoulos, 2002; Carpenter, 2006), further define clear limits to the Italian practices of urban regeneration. Despite the premise and attempts to integrate different activities and policies, in practice, interventions appear that are often focused on issues related to estate and physical regeneration of building and neighbourhoods. The difficulties to manage the participation of the multiplicity of actors and interests of the urban regeneration arena are also clear. Furthermore, it is not only in Italy that the issue of participation is often used as a rhetorical weapon to include intervention methods challenged by dual, and in many ways, contradictory requirements: on one hand, the involvement of the strong actors (investors, entrepreneurs), which guarantee the funding of initiatives; on the other hand, the participation from below, which supports the promotion of social cohesion and citizen empowerment (Tosi, 1994; Geddes, 2000). In fact, the most common form of participation concerns the organised interests (public and private) and rarely draws on the diffuse involvement of the population, although it is often possible to observe public consultations or interventions aimed at informing the public on decisions made. However, in the experiences of Italian regeneration, private actors do not seem to have found sufficient reasons to generate suitable investments to start a virtuous cycle halting and reversing processes of degradation through better training and employment. On the other hand, inclusive actions, designed to promote widespread citizen participation in decision making process, present both difficulties and limitations (see Camelli, 2005; Donolo, 2005; Regonini, 2005). Not only in Italy, but perhaps more in Italy than elsewhere, participatory practices are full of rhetoric and craftiness (Paba, 2003), often referring to purely ritual forms, already stigmatised in the late 1960s by Sherry Arnstein (Davoudi et al., 2009); to virtuous practices only feasible when it comes to micro-decisions relating to severely limited objectives and goals (and therefore not meeting the most important interests) (Cammelli, 2005), or even to resistence strategies toward projects or interventions (Paba, 2002).

Italys urban governance myths and illusions

Overall, the political institutional decentralisation process in Italy, and the innovations it gives rise to, seems to oscillate between the two forms of devolution described by Hudson (2005). According to this author, in fact,

what is claimed to be new and qualitatively different about more recent regional devolution is that it encompasses the power to decide, plus resources to implement decisions, at the regional level. Others, however, dispute this, and argue that what has been devolved to the regional level is responsibility without authority, power and resources [Hudson, 2005 pp. 620-621].

In Italy, as elsewhere, the decentralisation and the redesign of the relationship between the State and local authorities have not brought about a great deal of increased power transferred to local authorities, even for the apparent discrepancies between the skills transferred and the financial opportunities. Rather, they have contributed to the rethinking of the general framework of centre/periphery relationships, where the figure of most interest is the introduction of forms of relational partnerships between public and private actors, as well as of coordination and inter-institutional cooperation (Bobbio, 2002). This is no a trivial result. Through legislative change, a process of redefining political and administrative action was induced: the introduction of flexible regulatory instruments has consolidated, and made formal and formalized, the interaction and the establishment of agreements between a number of actors and interests, facilitating the practical administration of such relationships. The centrality assumed by local authorities in a wide range of policies (from those relating to environmental issues to the one concerning the promotion of development) allowed it to practice new forms of vertical subsidiarity. Moreover, the recognition of new forms of interest representation has led to the positive acceptance, hence not as a binding constraint but rather as a possibility, of the plurality and the articulation of the actors and interests involved in urban and regional transformations, facilitating the opening up of the decision making arena to traditionally excluded actors.

These elements can be traced down to the discovery of the virtues of cooperation within a social dimension dominated by pluralism and the subsidiarity, and of competition as the main route to allocation efficiency. Innovations introduced in the Italian context revolve therefore around two centres of gravity within the rhetoric of current policy making (Judge, Stoker and Wolman, 1995; Gaudin, 1999; Andersen and van Kempen, 2003; Uitermark, 2005; Cochrane, 2007): the negotiation of policies, associated with the constitution of agreements amongst central government, local authorities, and private interests, and the change in shape and modes of action of public bodies, with a gradual shift from a rather decision and regulatory role toward a role of pilotage, of direction or of accompaniment of the interactions amongst actors (Jessop, 1995; Sibeon, 2001; Kooiman, 2003).

According to Peters (2000), there is a significant difference between the traditional steering conception of governance, in which are still present forms of state coordination concerning the interactions between actors, and in which the State defines policy priorities and contracts between the different actors and different interests (and is therefore conceived as a guide to society and the economy), and the new modes of governance, whose distinguishing feature is both the plurality of interaction and the modalities of formal and informal regulation between public and private actors. It remains questionable into which of the two areas the Italian practices have entered with the greatest frequency and to the greatest extent. The amendment of Title V of the Constitution presents and expresses this ambivalence. This fits into the process of redefining the framework of powers between the State and local authorities (according to a traditional steering conception of governance). However, it also introduces a significant change in the mode of action of public bodies in urban government (which can be understood as an attempt to implement the new modes of governance). The new Title V in fact exceeds the traditional scope of planning, a technical work closely related to the regulation of land use, which has traditionally operated urban planning in Italy, by introducing the reference to territorial government (governo del territorio). This change in terminology in fact conceals a change in perspective and approach to the urban problems and to the procedures by which they are governed, by breaking up, at least in words, the Italian practice of public intervention in the government of cities of a purely regulatory nature. Although the term governo del territorio is vague and ambiguous, una buzzword senza tradizione, che ammette una vareità poco ordinate di significati, che rinvano a pratiche ancora più diversificate (a buzzword without tradition, with a variety of meanings which refer to more diverse practices) (Palermo, 2009, p. 43), it can be understood as an extended field, indicating a passage dalla sfera della semplice regolazione di usi e trasformazione del suolo a quello dello sviluppo insediativo e residenziale (from the sphere of simple regulation of land use to the sphere of settlement and residential development) (ibid, p. 43). From this perspective, the governo del territorio acts through the spatial coordination of a variety of sectorial policies (from land use to landscaping, from mobility to the protection of ecosystems, from promotion of local development to the enhancement of cultural and environmental goods), through the cooperation and coordination between multiple actors and interests as well as between different levels of government with the definition of partnership procedures, inter-institutional coordination, and negotiated planning.

Criticism, however, is not lacking and some aspects do appear quite paradoxical. As emphasized by Gualandi (2007, p. 551), the spatial planning system that is emerging in Italy since the constitutional amendment, outlines the move from

a rationalist and systematic model, in which to the hierarchy of plans corresponds a well-defined (and approved) hierarchy of interests to a model in which, even if from a theoretical point of view, may appear almost heretical [...] to refer to a hierarchy of interests [...], in reality is possible to observe [...] a phenomenon of centralisation and concrete ascension of decision-making, with the specification of a plurality of representation and decision models, often and somewhat improvised and lacking real legitimacy6.

In other words, the affirmation of the new keywords (subsidiarity, institutional pluralism, differentiation, citizens participation etc.) is accompanied, in practice, with a centralisation of decisions which derives mainly from the need for speed and efficiency in decision-making, whatever the outcomes they may bring.

In the field of experimentation and practice, the picture is the same. Signs of change in the way Italian cities are governed are accompanied by persistent problems that continue to be ignored by the public agenda, that are treated poorly or in an entirely ornamental fashion, or even bypassed altogether by proposals that leave out the problems (and opportunities) of Italian cities. These issues regard selected aspects of urban governance, for example environmental issues, in relation to energy saving in construction and building management or the reorganisation of traffic and mobility; quality of life and the increase of housing issues; the construction of multicultural cities and the growing social exclusion of large segments of the population, etc. There are also more general themes and issues related to the overall city government framework in Italy. One problem demonstrating the greatest inertia of Italian urban governance, which is often referred to but never acted upon, is the need to deal with the problem of metropolitan government, both from the institutional point of view (with the non-imposition of metropolitan areas or cities) and, especially, in terms of substantial actions. The issue of how to govern cities that are increasingly extended poses problems (and opportunities) of government that obviously extend beyond the boundaries of municipal competences. Italian urban governance, despite the experience of the strategic plans that question the metropolitan theme, is primarily a kind of local governance, which leads to the abandoning of other possible modes of action and other possible intervention levels. In fact, this is a perennial problem: Italy has traditionally left out the state level in the overall city development strategy. The creation of multilevel urban governance in Italy thus leaves out an important level, that of the State. This weakness has effects on the repetition, even on a citys matter, of the historical gap between the North and the South of the country, particularly concerning the experimentation of effective and innovative urban governances actions in the cities of the South (SGI, 2008).

According to Donolo (2005), Italian urban policies have got, at least potentially, two types of innovation. The first type pertains to the policies based on interaction between public institutions and civil society, where the coinvolgimento di risorse della società [...] [serve] non solo per la copertura del consenso, ma anche per la formulazione e limplementazione della politica (involvement of societys resources [...] is there not only to attain consensus, but also for the formulation and implementation of policies) (p. 40). The second type refers to the policies focused on the interaction between public institutions and private business interests, whose distinctive feature is the costruzione di partnership fra attori portatori di interessi (creation of partnerships between stakeholders) (p. 40). In the first case, the innovation lies in the possibility of producing public goods through social practices. In the second, linnovazione maggiore [...] non sta nellelemento negoziale, ma nei contesti regolativi in cui deve avvenire la contrattazione (the major innovation [...] is not the feature of negotiation, but the regulatory context in which bargaining must take place) (ibid, p. 44) (that is: the presence of a regulatory framework imposing constraints, methods, and evaluations). This distinction is reflected in those practices through which Italian cities are alternately (and uncritically) considered engines of economic growth, innovation centres, and key actors to promote and strengthen international competitiveness, but also to allowing the development of several forms of self-organisation, which constitute, in reality, assistive devices to counter the shortcomings of the market (Jessop, 2002). Therefore, some schizophrenia emerges between an interpretation of cities as centres of competition, on the one hand, and as laboratories for new forms of social cohesion, on the other hand. These two interpretations of Italian cities correspond to the definition of policies separately aimed at economic development or at social well-being.

Furthermore, over the last fifteen years, the pair competitiveness/cohesion has dominated the public agenda of urban policy not only in Italy (Fainstein, 2001; Boddy and Parkinson, 2004; Buck et al., 2005; Ache et al., 2008). Without actually considering the meanings of these two concepts, in the international debate and, more importantly, in the Italian practices, the two terms are considered either simply in opposition or linked by a dependency relationship: cohesion is namely seen as a precondition for achieving competitiveness. In Italian cities, the theme (and the rhetoric) of competitiveness has been interwoven with the processes of structural transformation and growth of urban economies, with the growing importance of the hypothesis that cities function as collective actors acting in a competitive context to obtain scarce resources (events, investments), with the real processes of physical and social changes, also related to the revitalisation of urban and real estate markets. Vice versa, the theme of social cohesion has been deployed in relation to the crises of the traditional modes of urban welfare, to the privatisation processes, and the outsourcing of public services, to the ongoing impacts of the two large urban demographic phenomena of the last decade (ageing and increasing immigration, legal and otherwise), to the new prominence of the housing problem and the emergence of security concerns. If, as highlighted by Fainstein (2001), the almost causal emphasis on the instrumental relationship between competition and cohesion leads one to forget the value of cohesion in itself and is a rhetorical trick of a new liberal mould, recognition of the limits of a purely instrumental conception of the relationship between entrepreneurial characterisation of the city and social justice is becoming increasingly clear (Harvey, 2008).

Overall, the change in Italian urban policies is reflected more in intention than in outcomes. The persistence of problems and the difficulties to enact changes in practices are two factors that characterise urban governance in Italy. Inertia, inefficiency, and lack of attention to the problems of the city are combined with the progressive output stage of cities as agents of public debate (cultural, social, and political), except in terms of warnings (such as the urban safety related to non-EU immigration, which has gained widespread coverage in Italian newspapers) and/or major events (such as media campaigns related to the Winter Olympics in Turin in 2006 or to the next Expo in Milan). The final outcome of this intense period that appeared to point to renewal is entirely uncertain. As stated by Palermo (2009, pp. 43-44), we remain poised between un rinnovamento ancora ampiamente incompiuto e una continuità sostanziale, che si limita solo a assumere forme discursive e manifestazioni empiriche apparentemente meno consuete (a still largely incomplete renewal and a substantial continuity, which is limited to taking only discursive forms and apparently less usual empirical manifestations).

References

Ache, P., Andersen, H. T., Maloutas, T., Raco, M. and Tasan-Kok, T. (eds.) (2008), Cities between Competitiveness and Cohesion. Discourses, Realities and Implementation, Berlin, Sprinter.

Amin, A. and Thrift, N. (2002), Cities: Re-imagining the Urban, Cambridge, Polity.

Andersen, H.T. and van Kempen, R. (2003), New trends in urban policies in Europe: evidence from the Netherlands and Denmark. Cities, 20(2), pp. 77-86.

Atkinson, R. (2000), Combating social exclusion in Europe: the new urban policy challenge. Urban Studies, 37, pp. 1037-1055.

Bagnasco, A. and Le Galès, P. (eds.) (1997), Villes en Europe, Paris, La Découverte.

Balducci, A. (2000), Le nuove politiche della governance urbana. Territorio, 13, pp. 7-15. [ Links ]

Belligni, S., Ravazza, S. and Salerno, R. (2009), Regime e coalizione di governo a Torino. Risultati di una ricerca. Polis, xxiii (1), pp. 403-421.

Bevir, M. (2002), Una teoria decentrata della governance. Stato e Mercato, 66, pp. 467-492.

Bobbio, L. (2002), I governi locali nelle democrazie contemporanee, Roma-Bari, Laterza.

Boddy, M. and Parkinson, M. (eds.), (2004), City Matters: Competitiveness, Cohesion and Urban Governance, Bristol, Policy Press.

Bolocan Goldstein, M. (2000), Un lessico per le politiche urbane e territoriali. Territorio, 13, pp. 122-133.

Brenner, N. (1999), Globalisation as reterritorialisation: the re-scaling of urban governance in the European Union. Urban Studies, 36, pp. 431-451.

Brenner, N. (2000), The urban question as a scale question: reflections on Henri Lefebvre urban theory and the politics of scale. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), pp. 361-378.

Brenner, N. (2004), New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Buck, N., Gordon, I., Harding, A. and Turok, I. (eds.) (2005), Changing Cities: Rethinking Urban Competitiveness, Cohesion and Governance, London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Cammelli, M. (2005), Considerazioni minime in tema di arene deliberative. Stato e Mercato, 73, pp. 89-96.

Cammelli, M. (ed.) (2007), Territorialità e Delocalizzazione nel Governo Locale, Bologna, Il Mulino.

Carpenter, J. (2006), Addressing Europes urban challenges: lessons from the EU urban community initiative. Urban Studies, 43, pp. 2145-2162.

Cassese, S. (2001), La Crisi dello Stato, Rome-Bari, Laterza.

Chorianopoulos, I. (2002), Urban restructuring and governance: north-south differences in Europe and the EU Urban initiative. Urban Studies, 39, pp. 705-726.

Cochrane, A. (2007), Understanding Urban Policy: a Critical Approach, Oxford, Blackwell.

Conti, S. (ed.) (2002), Torino nella Competizione Europea. Un Esercizio di Benchmarking Territoriale, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier.

Davoudi, S., Evans, N., Governa, F. and Santangelo, M. (2009), Le dimensioni della governance. In F. Governa, U. Janin Rivolin, and M. Santangelo (eds.), La Costruzione del Territorio Europeo. Sviluppo, Coesione, Governance, Rome, Carocci, pp. 35-64.

Debarbieux, B. and Vanier, M. (eds.) (2002), Ces territorialités qui se dessinent, Paris, LAube-Datar.

Dente, B. (1999), In un Diverso Stato, Bologna, Il Mulino.

Donolo, C. (2005), Dalle politiche pubbliche alle pratiche sociali nella produzione di beni pubblici? Osservazioni su una nuova generazione di policies. Stato e Mercato, 73, pp. 33-65.

Dowding, K. (2001), Explaining urban regimes. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(1), pp. 7-19.

Fainstein, S. (2001), Competitiveness, cohesion, and governance: their implications for social justice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(4), pp. 884-888.

Faludi, A. and Janin Rivolin, U. (eds.) (2005), Southern perspectives on European spatial planning. European Planning Studies, 13, pp. 195-331.

Ferrero G. (ed.) (2004), Valutare i Programmi Complessi, Interreg IIIB Medoc, CVT – Centri di Valutazione Territoriale, Savigliano, LArtistica Editrice.

Gaudin, J. P. (1999), Gouverner par contrat. Laction publique en question, Paris, Presses de Paris, Sciences Po.

Geddes, M. (2000), Tackling social exclusion in the European Union? The limits to the new orthodoxy of local partnership. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24, pp. 782-800.

Governa, F. (2004), Modelli e azioni di governance. Innovazioni e inerzie al cambiamento. Rivista Geografica Italiana, 1, pp. 1-27.

Governa, F. (2008), Teorie e pratiche di sviluppo locale. Riflessioni e prospettive a partire dallesperienza italiana. In E. Dansero, P. Giaccaria e F. Governa (eds.), Lo Sviluppo Locale al Nord e al Sud: un Confronto Internazionale, Milan, Franco Angeli, pp. 69-98.

Governa, F. and Saccomani, S. (2004), From urban renewal to local development. New conceptions and governance practices in the Italian peripheries. Planning Theory and Practice, 3, pp. 328-348.

Governa, F., Janin Rivolin, U. and Santangelo, M. (eds.) (2009), La Costruzione del Territorio Europeo. Sviluppo, Coesione, Governance, Roma, Carocci.

Gualandi, F. (2007), Dal governo del territorio al territorio .del Governo?. In M. Cammelli (eds.), Territorialità e Delocalizzazione nel Governo Locale, Bologna, Il Mulino, pp. 551-568.

Gualini, E. (2004), Multi-level Governance and Institutional Change. The Europeanization of Regional Policy in Italy, Aldershot, Ashgate.

Harvey, D. (2008), The right to the city. New Left Review, 53, pp. 23-40.

Hudson, R. (2005), Region and place: devolved regional government and regional economic success?. Progress in Human Geography, 29(5), pp. 618-625.

Imrie, R. and Raco, M. (1999), How new is the new local governance? Lessons from the United Kingdom. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 24, pp. 45-63.

Janin Rivolin, U. (2003), Shaping European spatial planning. How Italys experience can contribute. Town Planning Review, 74 (1), pp. 51-76.

Jessop, B. (1994), Post-fordism and the State. In A. Amin (ed.), Post-fordism. A Reader, Oxford, Blackwell, pp. 251-279.

Jessop, B. (1995), The regulation approach, governance and post-fordism: alternative perspectives on economic and political change. Economy and Society, 24(3), pp. 307-333.

Jessop, B. (2002), Liberalism, neoliberalism, and urban governance: A State-theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34(3), pp. 452-472.

Judge, D., Stoker, G. and Wolman, H. (eds.) (1995), Theories of Urban Politics, London, Sage Publications.

Kooiman, J. (2003), Governing as Governance, London, Sage.

Lascoumes, P. and Le Galès P. (eds.) (2004), Gouverner par les instruments, Paris, Les presses de Sciences Po.

Lauria, M. (ed.) (1996), Reconstructing Urban Regime Theory, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications.

Le Galès, P. (2002), European Cities, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Logan, J. R. and Molotch, H. (1987), Urban Fortunes: the Political Economy of Place, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Mazza, L. (2000), Strategie e strategie spaziali. Territorio, 13, pp. 16-28.

Molotch, H. (1976), The city as a growth machine. The American Journal of Sociology, 82, pp. 309-331.

Mossberger, K. e Stoker, G. (2001), The evolution of urban regime theory. The challenge of conceptualization. Urban Affairs Review, 36(6), pp. 810-835.

Osmont, A. (1998), La gouvernance: concept mou, politique ferme. Les Annales de la recherche urbaine, 80-81, pp. 19-26.

Paba, G. (2003), Movimenti Urbani, Pratiche di Costruzione Sociale della Città, Milan, FrancoAngeli.

Paba, G. (ed.) (2002), Insurgent City. Racconti e Geografie di unaltra Firenze, Livorno, Mediaprint.

Palermo, P. C. (2009), I Limiti del Possible. Governo del Territorio e Qualità dello Sviluppo, Roma, Donzelli.

Parkinson, M. (1998), Combating Social Exclusions: Lessons from Area-based Programmes in Europe, Bristol, The Policy Press.

Pasqui, G. (2008), Città, Popolazioni, Politiche, Milan, Jaca Book.

Perulli, P. (2004), Piani Strategici: Governare le Città Europee, Milan, Franco Angeli.

Peters, B. G. (2000), Governance and comparative politics. In J. Pierre (ed.), Debating Governance. Authority, Steering, and Democracy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 36-53.

Pierre J. (2000a), Understanding governance. In J. Pierre (ed.), Debating Governance. Authority, Steering, and Democracy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 1-10.

Pierre, J. (ed.) (2000b), Debating Governance. Authority, Steering, and Democracy, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Purcell M. (2006), Urban democracy and the local trap. Urban Studies, 43 (11), pp. 1921-1941.

Regonini, G. (2005), Paradossi della democrazia deliberativa. Stato e Mercato, 73, pp. 3-31.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1997), Understanding Governance. Policy Networks, Governance, Reflexivity and Accountability, Buckingham, Open University Press.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (2000), Governance and public administration. In J. Pierre (ed.), Debating Governance. Authority, Steering, and Democracy, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 54-90.

SGI (Società Geografica Italiana) (2008), LItalia delle Città fra Malessere e Trasfigurazione, Roma, editor G. Dematteis.

Sibeon, R. (2001), Governance in Europe: concepts, themes and processes. Conferenza Internazionale Governance e Istituzioni: il ruolo delleconomia aperta nei contesti locali, 30-31 Marzo, Forlì.

Stoker, G. (1998), Governance as theory: five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 155, pp. 17-28.

Stoker, G. and Mossberger, K. (1994), Urban regime theory in comparative perspective. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 12-2, pp. 195-212.

Stone, C. N. (2005), Looking back to look forward: Reflections on urban regime analysis. Urban Affair Review, 40(3), pp. 309-341.

Torino Internazionale (2000), Il Piano strategico della città, http://www.torino-internazionale.org (last access: October 2009).

Torino Internazionale (2006), 2.° piano Strategico dellArea Metropolitana, http://www.torino-internazionale.org (last access: October 2009).

Tosi, A. (1994), Abitanti. Le Nuove Strategie dellAzione Abitativa, Bologna, Il Mulino.

Tubertini, C. (2007), Riforma costituzionale e sistema locale dei servizi sociali: tra territorializzazione e centralizzazione. In M. Cammelli (ed.), Territorialità e Delocalizzazione nel Governo Locale, Bologna, Il Mulino, pp. 771-800.

Uitermark, J. (2005), The genesis and evolution of urban policy: a confrontation of regulationist and governmentality approaches. Political Geography, 24, pp. 137-163.

Vandelli, L. (2000), Il Governo Locale, Bologna, Il Mulino.

Vanier, M. (1999), La recomposition territoriale. Un grand débat idéal. Espaces et Sociétés, 96, pp. 125-143.

Notes

1 I accept the ambiguity and the risk of a purely rhetorical or instrumental use of the term governance as a baseline datum (see Rhodes, 1997; Osmont, 1998; Pierre, 2000a; Governa, 2004; Governa, Janin Rivolin and Santangelo, 2009), which will then be discussed with reference to the specific incidence of urban policies in Italy. Suffice to recall here that often, in more simplistic and streamlined interpretations, the term governance is used to indicate a (generic) improvement in relation to the past (in critical terms, for example, Imrie and Raco, 1999). The word governance is thus used as a panacea to solve every problem, without taking into account the many significances that are layered around the term, the many meanings with which it has been (and still is) used, the many fields of the exercise of government where governance models are used (Rhodes, 1997). This attitude also tends to favour a prescriptive-normative conception of the term (which emphasises how we should act in a certain situation or, more generally, to change the style of government) rather than analytical-descriptive (describing a particular situation or a particular government practice) (Bevir, 2002).

2 For an interpretation of urban policies as public policies that, as such, exist and become enacted through a selection of political instruments, see Lascoumes and Le Galès (2004).

3 In the case of the minimal State, according to Stoker (1998, p. 18), governance is understood only as the acceptable face of spending cuts.

4 According to Faludi and Janin Rivolin (2005), the specific style of policy making of Southern European countries is a key element in building a Mediterranean way to European policies.

5 Dopo aver esplorato modelli improbabili di governo del territorio, mediante piani prescrittivi di notevole grado di dettaglio ed esteso orizzonte temporale (una singolarità italiana); dopo aver sperimentato, con decenni di ritardi ed esiti controversy, I modelli della programmazione strutturale e della progettazione integrate che dispongono di esperienze mature in altri contesti evoluti; or ail nostro paese si dedica più volentieri ai più agevoli esercizi di pianificazione strtaegica, che per definizione implicano minori responsabilità di scelta e di azione (After having explored unlikely models of governo del territorio through prescriptive plans of a considerable degree of detail and extended time horizon (an Italian singularity); after having experimented, with decades of delays and controversial results, the structural models of planning and integrated programming that have interesting experiences in other contexts; now our country is willing to spend on strategic planning exercises, which, by definition, involve minor responsibilities in choice and action) (Palermo, 2009, p. 113). According to Palermo, Italy suffered substantial delay in the testing of more effective and efficient models of urban governance. Despite the interest that potentially is possible to find in some experimentations, when the lag is being made up, and action models already tested elsewhere are spreading in Italy, the Italian tendency is to produce and reproduce the più banali e meno ricche di potenzialità innovative (most mundane and least rich in innovative potential) (ibid, p. 113) experiences, as happens according to the same author for the current spate of strategic plans.

6 da un modello razionalista e sistematico, nel quale alla gerarchia dei Piani corrispondeva una ben definite (e riconosciuta) gerarchia tra gli interessi ad un modello in cui se da un punto di vista teorico potrebbe apparire quasi eretico [...] parlare di gerarchia di interessi [...] in realtà si assiste [...] ad un fenomeno di accentramento e di concreta ascensione dei processi decisionali, con lindividuazione di una pluralità di sedi e moduli decisionali, spesso alquanto estemporanei e privi di effettiva legittimazione.

** Giuseppe Dematteis, Politecnico di Torino, Matteo Goldstein Bolocan and Gabriele Pasqui, Politecnico di Milano, read an early version of this text. I thank them with affection and hope to be able to take due account of their just criticisms and suggestions.