Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social n.197 Lisboa 2010

Uneven development and neo-corporatism in the Greek urban realm

Ioannis Chorianopoulos*

* Departement of Geography, University of the Aegean, University Hill, Mytilene, 81100, Greece. e-mail: ichorian@geo.aegean.gr

This paper portrays the urbanisation and governance profile of Greek cities and explores their capacity to respond to EU calls for enhanced competitiveness and synergistic policy-making. The distinctiveness of the Greek urban example, it is argued, is not well adjusted to European spatial priorities and neo-corporatist modes of intervention. Two case study cities illustrate the argument: Keratsini-Drapetsona, facing the realities of de-industrialisation, and Iraklion, a city on the island of Crete with dynamic development indicators. The paper concludes by discussing the mode of incorporation of cities in the current National Strategic Reference Framework (2007-2013).

Keywords: Greece; urbanisation; governance; competitiveness; neo-corporatism.

Desenvolvimento desigual e neo-corporativismo na esfera urbana Grega

Este artigo retrata o perfil de urbanização e de governança das cidades gregas e analisa as suas reacções face às propostas da UE de desenvolvimento de políticas mais competitivas e sinergéticas. Argumenta-se que as especificidades da esfera urbana grega não se encontram adaptadas às prioridades espaciais europeias e aos correspondentes modos neo-corporativos de intervenção. Estudos de caso em duas cidades ilustram este argumento: Keratsini-Drapetsona, enfrentando a desindustrialização; e Iraklion, uma cidade na ilha de Creta, que apresenta bons indicadores de desenvolvimento. O artigo conclui com uma discussão sobre a incorporação das cidades gregas no presente Quadro de Referência Estratégico Nacional (2007-2013).

Keywords: Grécia; urbanização; governança; competitividade; neo-corporativismo.

Introduction

The competitive position of the European economy against those of the USA and Japan deteriorated sharply during the late 1980s and early 1990s1. This, together with lower trade barriers through reductions in the rate of customs duties, already agreed at that time in the Uruguay Round of the GATT multilateral trade negotiations, prioritised the issues of European economic adaptability and competitiveness in the Maastricht Treaty (CEC, 1994a, p. 3). The White Paper on growth, competitiveness and employment, highlighted the importance of flexible and decentralised policies as a means to enhance European economic potential. This policy perspective centres on the role of the local political level, identified as the most appropriate in generating co-operation processes and endogenous, place-specific, development paths2 (CEC, 1993a, p. 9).

The increased responsibilities of the local level illustrate the gradual adaptation of Community policies to the rapidly changing economic circumstances apparent since the 1980s. The upgraded role of the local level in pursuit of national and European economic objectives is approached in Community documents through the analytical framework of globalisation and the shift from industries to services [that] [ ] enhanced the importance of space for economic development, [and] [ ] reinforced the potential of cities as autonomous creators of prosperity (CEC, 1997, p. 6 and p. 8). Urban areas, in this context, are portrayed as the main source of prosperity [as] [ ] they contribute disproportionately more to regional or national GDP compared to their population (CEC, 1997, p. 4). In terms of social disparities, the enhanced importance of cities in Community policies is approached on the basis of concentrated social problems in urban areas linked to low educational attainment rates, high (above European averages) urban unemployment rates, and social exclusion phenomena. Such concerns have kept a certain momentum ever since, and currently mark EU spatial policy prioritisations. Urban policy is now an explicit part of the National Strategic Reference Frameworks (CEC, 2007), a development that underscores the increased importance of the EU stance to the prospects of European cities. Within this framework, this article focuses on Greece.

Greece joined the EU in 1981. The extent to which the country was not in a position to participate in an enhanced competitive context is indicated by the underdeveloped state of key aspects of the economic environment, such as physical infrastructure provision and workforce qualifications3. The political prioritisation of the acceleration of economic integration aggravated concerns about the capacity of the country to adjust along competitiveness lines. Greek cities were gradually called on to participate in this drive for competitiveness. The results, however, have not been encouraging. With the exception of Athens, Greek cities lag behind in critical competitiveness indicators (DATAR, 2003), exhibit poor economic performance, and fall short of participating in the European urban core, the area that encompasses the majority of economically dynamic European cities (ESPON, 2006). On the contrary, it appears that the enhanced inter-urban competition that followed the Single European Act (1986), and the subsequent diminution of protectionist barriers to trade and investment, exposed the traits of an urban system which faces embedded difficulties in grasping the development opportunities opened up by EU integration. EU urban policy aims specifically to remove obstacles to growth, strengthen competitiveness, and promote sustainable development (CEC, 2006a). It is the responses of Greek cities to EU urban policy that this article aims to explore.

The article is organised into three parts. The first explores the ways in which cities were defined as a policy problem by the EU, also highlighting the traits of EU urban policy. The second section focuses on Greece. It draws attention to the particularity of the economic and socio-political realities of the post-war period of rapid urbanisation, underscoring the distinctive context in which Greek cities were called on to promote restructuring strategies. This is followed by a brief description of recent politico-administrative attempts seeking to enhance the regulatory attributes of the local level. The third part of the paper presents the governance responses of Greek cities to competitiveness-oriented prioritisations. The case-study cities are Keratsini-Drapetsona and Iraklion, empirical analysis spanning more than a decade of urban interventions. Research findings suggest significant transformations in the way that urban issues are approached, defined, and administered in the country – changes that show the influence of the EU urban policy discourse. The distinctiveness of the urbanisation and governance characteristics of Greek cities is, however, still present, shadowing EU policy prioritisations and questioning the relevance of the EU urban approach to the local context. The paper concludes by presenting current urban policy directions in Greece, as defined by the incorporation of the urban dimension into the National Strategic Reference Framework.

Europe and the City

Following a period of brief experimentation with a series of innovative urban intervention schemes, the increased importance attached by the EU on the urban level was reflected in the Maastricht Treaty (CEC, 1992a). The amended framework regulating the responsibilities of the Community and national and local level authorities in structural policies re-affirmed the subsidiary character of the Communitys involvement at the national level. In this light, EU urban policy priorities and programmes were to be filtered at the national level, adapting them to local political-administrative structures. The subsidiarity concept, however, as adopted in Maastricht, also recognised the enhanced role of the local level in the pursuit of the Communitys socio-economic objectives and by promoting links between the local and Community levels upgraded the role of local authorities within the EU spatial policy framework4. The rationale for the launch of decentralised policies also led to the extension of the partnership principle to include competent authorities and bodies, [as well as] [ ] economic and social partners, designated by the member State at national, regional, local or other level [ ] in pursuit of a common goal (Article 4 of Framework Regulation CEC, 1993b, p. 48)

The incorporation into a single EU programme of all the political authorities, leading projects, as well as the relevant public and private sector interest groups, signifies the promotion of governance structures as the basis of EU spatial policies. In this respect, collaboration aims at unlocking the local relational dynamic, triggering synergistic responses to local challenges. Such development-oriented neo-corporatist stances were noted in a number of European cities that managed to reverse de-industrialisation, exhibiting a restructuring record marked by high growth rates and population recentralisation (Cheshire, 1995; Camagni, 2002). The prioritisation of governance policies as the selected policy form for the advancement of funding targets was applied explicitly at the urban level with the launch of the URBAN Community Initiative (1994-2006).

The introduction of URBAN was justified on the grounds of improved co-ordination of the structural instruments which, in accordance with the subsidiarity principle, would (i) strengthen support for cities, especially those under objectives 1 and 2; (ii) promote innovative policies and local level exchange of experience networks; (iii) extend the inclusion of the urban dimension in the formulation of various Community policies as a means to achieve more spatially focused economic development objectives (CEC, 1994c, p. 1).

The key novel aspect of URBAN was the emphasis placed on the participation of local level interest groups in all programme phases (CEC, 1998a, p. 2). The inclusion of local authorities in partnership mechanisms [with] [ ] economic and social bodies, was viewed as essential for tackling urban deprivation and promoting economic competitiveness (CEC, 1998b, p. 6). The relevance of the EU urban approach to Greek urban realities of administrative centralisation and limited experience of local collaborative arrangements is explored next. This analysis emphasises key qualities of the urban economic and socio-political space that distinguish the governance profile of Greek cities from the ideal-typical restructuring examples that inform EU urban policy.

Greek urban legacies

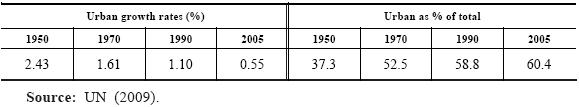

The debate over European urbanisation patterns correlates socio-economic transformation processes with distinct stages of urban spatial evolution (CEC, 1992b, pp. 71-72). The 1960-1980 decline of population in urban agglomerations in Northern Europe, for instance, was approached as the spatial manifestation of industrial, employment, and residential decentralisation processes (Berg et al., 1982, pp. 29-36). Also, the emergence of a variation of urban development patterns with some urban regions displaying recentralisation tendencies since the 1980s was correlated with the growth of service sector employment and the enhanced urban socio-economic embeddedness of economic activity (Cheshire, 2006). In this framework, Greece represents a distinct example. Table 1 displays the average urban growth rates for the period 1950-2005, also indicating the rate of urban population expansion as a percentage of the total population.

Urban population growth rates in Greece (1950-2005)

[table 1]

As noted in Table 1, the wave of urbanisation experienced in Greece in the early post-war period was substantial and extensive. What is also of note in the above figures is the continuous, albeit at lower rates, pattern of urban centralisation, a trend that raises the question of urban economies and pull factors that originally drove and currently sustain the influx of population in cities. A look at the sectoral distribution of labour force during the last decades (Table 2) sheds light on this trend.

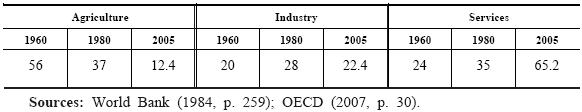

Sectoral distribution of labour force (1960-2005)

[table 2]

At first glance, Table 2 depicts the gradual modernisation of the countrys employment structures, from the dominance of the agricultural sector in the 1960s, to the key role of services in the 2000s (CEC, 1992b, p. 67). Looking closer, however, the significant rates of service employment during the early period of urban centralisation are noteworthy (Williams, 1984, p. 8; Adrikopoulou, Getimis and Kafkalas, 1992, p. 214). In fact, the working population engaged in service activities surpasses that of industry throughout this period. The moderate contribution of industry as a source of employment during the early period of urban growth indicates the constrained capacity of the sector to influence migration patterns. The narrow manifestation of internal economies of scale in industrial firms (Hudson and Lewis, 1984, p. 200), as well as the few signs of external economies of localisation affecting the spatial pattern of industrial development5, further support this argument. The limited role of industry as an initial pull factor to urban centres and the precise nature of tertiary sector employment, dominated by public administration, tourist services, and self-employment, points to the informality of migrant job expectations (Tsoukalas, 1986, p. 184). Distinct spatial and socio-political landscapes are related to this particularity.

Urban regulation

Despite the weak role of industry as an urban immigration pull factor, post-war Greece displays a strong economic growth record6, also based on the gradual industrialisation of the economy (see Table 2). The socio-institutional profile of the economy, however, differs substantially from the ideal-typical northern European industrial development examples of the era. Post-war political realities in the country are time-framed by the Civil War (1945-1949) and the military dictatorship (1967-1974). During this time, trade-union representation was either restricted or utterly prohibited (1967-1974), arresting the emergence of consensual wage relations and corporatist policies. Political legitimacy was claimed on the basis of urbanisation-related economic expansion. It is in this context that national authorities tolerated and accepted informal economic activities, estimated at 25 per cent of GDP at factor cost throughout this period (Ioakimidis, 1984, pp. 42-43). Authoritarian rule and the paucity of national socio-political compromises were also reflected locally.

Political repression was combined in Greece with a mode of political-administrative centralisation aimed at arresting the surfacing of opposing political voices. Local authority income, for example, was collected on behalf of the local state by the Ministry of Finance, placing strict controls on local spending. More characteristically, the national authorities appointed mayors and public sector officials at the local level, impeding the emergence of local interests (Chlepas, 1997). The limited regulatory experience of the local level in the post-war period influenced the direction of changes attempted with the re-establishment of democracy (1975), suggesting path-dependent endogenous development constraints.

The re-introduction of local elections (1975) was accompanied by an expansion of local level bureaucracies and functions. In the absence of an active local socio-political scene, however, the new national political scene exerted strong influence on local regulatory traits. Local authority financial competences, for instance, did not increase substantially and did not devolve. More than 80 per cent of local income is still levied centrally and is subsequently distributed at the local level on the basis of a number of rigid, population-related criteria (Lalenis and Liogkas, 2002, p. 443). Such inflexibility renders the financial activity of Greek local authorities last amongst the EU 15 (Council of Europe, 2001; Petrakos and Psycharis, 2004). More importantly, it inhibits the formation of local spaces of regulation. The restricted capacity of local authority to actively finance and execute locally decided development plans limits interaction with interest groups, directing the latters attention toward the respective gate-keepers at the national level (Chorianopoulos, 2008). Authoritarianism and the absence of corporatist socio-political arrangements in the post-war period of economic modernisation are thus still reflected in the underdeveloped relational traits noted locally.

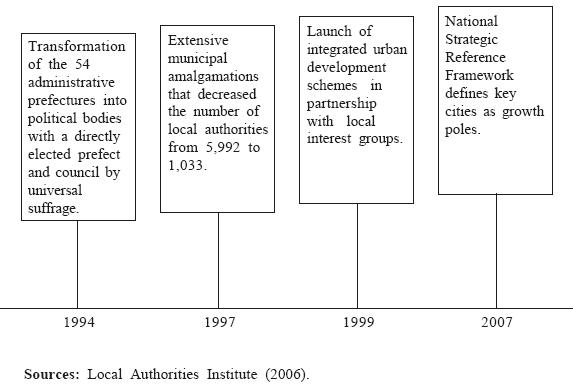

However, recent developments, portrayed diagrammatically in Figure 1, indicate territorial restructuring attempts seeking to strengthen the regulatory and developmental role of the local level.

Key recent state spatial restructuring attempts

[figure 1]

As indicated in Figure 1, the 1990s saw the introduction of a number of challenging endogenous development prospects. The emergence of politically accountable prefectures (1994) in conjunction with municipal amalgamations (1997) redefined the local political-institutional arena, acting as a stimulus to policy partnerships and innovation. Such changing geographies of regulation reflect EU spatial policy priorities. They do not, however, occur in a vacuum. Previous urban policy choices influence restructuring directions. The 1999 Integrated Urban Interventions Act, for instance, marks a shift from the dominant local authority preoccupation with infrastructural improvements, enabling the local state to embark on thematically broader partnership activities with interest groups. The Act, however, prohibits any partner organisation from initiating or running projects, assigning this responsibility solely to the local authority (Local Authorities Institute, 2006).

The EU conceptualisation of urban intervention, therefore, differs from local realities. EU urban policy is informed by resurgent cities: areas that experienced de-industrialisation and managed to effectively restructure their economy based on concerted and locally-defined governance responses (Storper and Manville, 2006). De-industrialisation was never a major urban concern in Greece. The key role of the service sector as an employment provider during urban centralisation shaped distinct urban landscapes. Because it followed the emergence of urbanised economies, industry is primarily located on the urban outskirts (Leontidou, 1990). Its subsequent withdrawal, in turn, affected primarily detached parts of the urban fabric7. Moreover, limited local articulation of interests questions the effectiveness of a policy intervention aimed at triggering locally defined synergistic actions. It is in this context of centralised political-administrative structures and territorial experimentation that the impact of EU urban policy on Greek cities is going to be explored.

The case-studies are Keratsini-Drapetsona and Iraklion; selected on the basis of their record of URBAN Initiative participation, the programme that defined the current mode of EU urban intervention (CEC, 2006b, p. 2). Fieldwork consisted of visits to cities during the programming period and interviews with local authority personnel responsible for running URBAN, as well as with key private and voluntary sector partner organisations. Interviews were semi-structured, based on an outline of key questions that explored the following themes: (i) the mode of local involvement in URBAN; (ii) the relationship between the local level, the national authorities, and the EU during implementation; (iii) the participatory traits of local interest groups (small and medium sized company associations, Chambers of Commerce, as well as community and educational bodies) in URBAN.

Analysis starts with a brief presentation of the socio-economic characteristics of the urban areas of interest, and focuses, subsequently, on local governance structures and responses.

Keratsini-Drapetsona

The Keratsini-Drapetsona URBAN programme centred on two neighbouring municipalities in the Piraeus metropolitan belt with 71,000 and 14,000 inhabitants, respectively. As Keratsini and Drapetsona are adjacent to the industrial docks of the Piraeus port, the employment structures of the area have been determined by the dominance of secondary sector activities (transport, storage, and oil refineries). However, the restructuring of transport industries since the 1970s had a major impact on local unemployment levels8. The local URBAN project promoted five broad categories of targets including: a) support for industrial sectors facing structural problems; b) advancement of employment policies; c) development of social policy measures; d) improvements in the physical environment; and e) development of the administrative and technical capacity of the municipalities to promote programme implementation (Keratsini-Drapetsona, 1996, pp. 42-43).

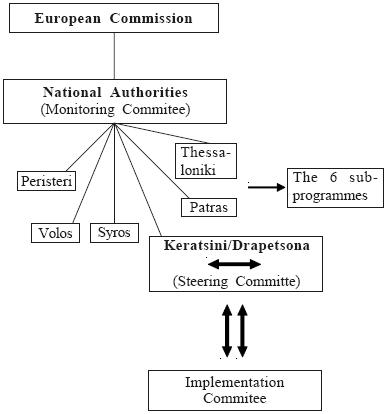

Administration in Greece took the form of a single URBAN programme co-ordinated by the national authorities with six sub-programmes implemented at the local level. There was no bidding process amongst Greek cities for participation in the Initiative. The six URBAN sub-programmes and the corresponding local authorities9 were nominated at the national level by the ministries responsible for the implementation of the second Community Support Framework (1994-2000). Information about URBAN was sent to Keratsini-Drapetsona local authorities by the Ministry of Environment and Planning (1994), and the two municipalities were asked to submit a combined Action Plan based on local policy priorities (Tsaousis, interview). The preparation of URBAN was assigned to the Development Corporation of Piraeus Municipalities (ANDIP), a municipal organisation founded in 1986 with its main areas of activity being the conduct of socio-economic studies and the implementation of various policies decided upon by the two local authorities. The local Development Corporation also had a central position in the administrative structures of the Initiative, portrayed diagrammatically in Figure 2.

The administration of URBAN in Greece

[figure 2]

At the national level, URBAN was regulated by a Monitoring Committee consisting of representatives from the respective Ministries10, the European Commission, national sectoral associations, and interest groups, as well as by local authority representatives from the six sub-programmes. The leading role in this Committee was exercised by the Ministerial tier, which had the responsibility to co-ordinate the local URBAN sub-programmes and guarantee the alignment of their targets with the overall Community Support Framework priorities (Ministry of Environment and Planning, 1995). Two regulatory bodies were formed at the local level. First, the Local Steering Committee, comprising representatives from the Municipal Councils, the local development corporation, the corresponding National Ministries, and local interest groups. The local Steering Committee held monthly meetings and decided on projects and budget arrangements suggested by the second tier of the local URBAN administration, the Implementation Committee. In Keratsini-Drapetsona, the URBAN Implementation Committee was the local Development Corporation (Iggliz, interview; Ministry of Environment and Planning, 1995 and 1996, p. 8).

The centralised traits of the Greek administrative system had a strong impact from the very outset of URBAN, when national authorities controlled and selectively channelled local level access to the Initiative. In subsequent programme phases, the strong national grip on URBAN took various forms. The most prominent example comes from the policy areas of vocational training and small and medium sized enterprise (SME) support, which featured prominently in both the respective Regional Operational Programme and in the URBAN Initiative. In order to tackle the issue of overlapping targets, the URBAN Monitoring Committee of Greece issued a statement explaining, actions relevant to the development of SMEs will be organised centrally by the Ministry of National Economy, while, with regard to the development of vocational training programmes, these are to be implemented by the respective national organisations and Community Support Framework programmes assisted by the ESF (Monitoring Committee of Greece URBAN, 1995, p. 1). In real terms, this policy assigned a mediating role to local authorities, which ended up forwarding applications for subsidies from the local private and voluntary sectors (SMEs, community associations) to the national authorities (Development Corporation of Piraeus Municipalities, 1997). More importantly, the assumption of key parts of the programme by the national authorities arrested the opportunity for the development of an integrated approach to local problems. National authorities undertook the task of organising and implementing the majority of socio-economic regeneration measures, leaving local authorities to work on a number of physical infrastructure schemes funded by URBAN.

A second trait of Greek local governance noted in the case-study cities is the limited involvement of private and voluntary sector groups in programme activities. According to the local authority interviewee, the record of cooperation between local authorities and interest groups is limited and their presence in the URBAN Steering Committee was of an overall ceremonial character (Tsaousis, interview). It is worth noting, however, that it was during the final phases of the respective URBAN programme that national legislation permitted and encouraged the materialisation of synergistic and integrated urban development schemes (see Figure 1). The participatory governance and integrated interventions concepts were particularly novel in Greece at that time, putting ill prepared local authorities and interest groups into the spotlight. The experience gained through URBAN, and the impact of the aforementioned institutional adaptations to EU spatial policy prioritisations, was more visible in the second phase (2000-2006), explored next in the city of Iraklion.

Iraklion

Iraklion is situated in the North-Western part of the island of Crete and also presents a case of de-industrialisation related intervention. The difference between the two URBAN case-studies, however, is that de-industrialisation in Iraklion affected primarIIy a relatively isolated part of the urban fabric, the old industrial port. This area apart, the city boasts a successful and multi-faceted restructuring record, suggesting an active local political level (Asprogerakas, 2004). Examples range from the successful lobbying of the International Olympic Committee and the (exceptional) hosting in the city of a number of Athens 2004 Olympic Games events, also accompanied by significant investment in physical infrastructures. Longer term development strategies include the involvement of the city in two EU related local authority networks and the consequent participation in a number of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) projects11. The extent to which the city is actively seeking to grasp development opportunities is indicated by the 2001 opening of the Brussels Office of the Iraklion Development Corporation, aiming to [ ] inform, negotiate, network and lobby directly in Brussels on behalf of the prefectures municipalities (Iniotaki, Interviews). It was in this context of awareness that funding opportunities that would facilitate intervention in the old industrial port were sought. Thus, when the commission publicised the second phase of the URBAN Initiative, Iraklion did not let this opportunity slip away.

The Iraklion URBAN (2000-2006) programme focused on three adjacent districts in the North-West part of the city, with a population of 20,000: (i) Agia Triada; (ii) Kaminia; (iii) Agios Minas. The port-related industrial activities that had dominated the area since the post-war years were severely affected by de-industrialisation, a trend that resulted in a deteriorating urban fabric and unemployment rates reaching 18 per cent of the local labour force; twice the citys average. Moreover, during the 1990s, comparatively lower housing rents attracted significant numbers of immigrant workers into the area, accentuating already noticeable social exclusion problems. Iraklion-URBAN set three main goals for the area: (i) physical and environmental regeneration that builds upon the local cultural and architectural heritage; (ii) job creation and small and medium-sized enterprises development schemes; (iii) the establishment of a new social service network aimed at tackling social exclusion (Iraklion URBAN II, 2001).

A number of changes were noted in the implementation of the second phase, indicating a process of change in action. The most characteristic example comes from the realm of central-local relations, suggesting a trend toward a more open and decentralised institutional environment. In URBAN II, this was apparent right from the launch of the Initiative. The substantial budget that accompanies URBAN projects attracted the attention of Greek local authorities, which announced a call for proposals open to all eligible cities. The Ministerial tier responded accordingly. In total 40 applications were submitted and three local authority schemes12 were selected and approved, based on a range of qualitative and quantitative criteria (Manola, Interviews). In subsequent stages, two new single-purpose administrative units were set up at both national and local levels, the Steering Office and the URBAN Office respectively, directly linking the two tiers and speeding up problem solving and project implementation. Despite decentralisation tendencies, however, past institutional choices left their own imprint on this process of change.

Leaving the two new administrative units aside, the political structure of URBAN II retained its centralised traits noted in the first phase of the Initiative (see Figure 1). The Ministerial level continued to hold decision-taking responsibility over all three sub-programmes, an arrangement that reflected national URBAN financial obligations in the light of the non-participation of local authorities in co-financing. As a result, project funding was not in tune with the implementation process. Actions related to support for SMEs, for instance, were funded and launched in May 2007 a year after the end of the official programme period blocking any externalities expected to materialise from the multifaceted URBAN approach to intervention. In policy areas where action relied solely on local initiative, however, procedures were more efficient.

Local authorities in Iraklion managed to involve the majority of local stakeholders in URBAN13, promoting a well discussed and integrated action plan for the area in question. Interest group involvement was also reflected in the implementation stage, marking a stark contrast to past experience in the country. The University of Crete, for instance, organised and implemented the conversion of an old warehouse into the citys new natural history museum, administering directly 25.8 per cent of the URBAN budget. However, the role of other-than-public-sector interest groups in the implementation phase had to be adjusted to the national regulatory framework that guides such schemes. The local Chamber of Commerce and Industry, for instance, a private sector organisation, was not in a position to directly administer URBAN funds. Instead, it provided vocational training to local residents through the contracting-out of its services (Katharakis, Interviews).

Innovative policies were also noted in other areas. URBAN funds facilitated the creation of a new social service network in the old port. Activities assumed by the local authority include, amongst others, nursery and kindergarten facilities, a counselling unit for the young and the elderly, a home-care unit, a language training centre oriented to minority needs, a hostel for the homeless, and a drug rehabilitation centre (Iraklion URBAN II, 2001). The fact that local authorities have limited room for influencing the investment layout of local income casts doubt on the financial viability of these schemes in the long run. The very development of this structure, however, is seen locally as a concrete claim for change; a lever that would enable the mitigation of rigid national controls that predetermine local spending (Kokori, Interviews).

Conclusions: the challenges ahead

Key differences were noted in the responses of the two case-study cities to URBAN, marked by a higher degree of effectiveness with which Iraklion approached and implemented the Initiative. Such differences reflect the particularity of local economic and socio-political circumstances. They are also suggestive, however, of the gradual impact of EU policies on Greek local governance. As discussed, during the time-span of URBAN (1994-2006) a number of territorial restructuring reforms sought to strengthen the regulatory and developmental profile of the local political level, recognising its role in development prospects. It was in this experimentation period that local Greek authorities staked out their participation in URBAN II, opposing the controlling role of the national administration in EU urban programmes. It was also in this time period that Iraklion re-oriented its development vision by opening up an office in Brussels, and structured a sound integrated intervention attempt in deprived port quarters. Institutional change, however, takes place in response to past experiences. The reliance of the local level on national finances was detected in both cities, arresting the emergence of local coalitions in the SME area. More characteristically, the limited involvement of private and voluntary sector groups was noted, reflecting the commanding role of the local political level in any integrated intervention attempt.

The EU urban policy envisages a mode of local mobilisation that encompasses key stakeholders, creating a mediatory platform regulated by the local political level. In this ideal-typical neo-corporatist structure, participant policy views are expected to assume equal weight, different opinions to be consensually synthesised into a clear position (an action plan), with resources to be shared. The materialisation of synergy, in turn, spreads associated risks while simultaneously promoting a mutually binding involvement to restructuring. Underdeveloped governance experiences and rigid administrative hierarchies, however, render Greek localities unprepared for participating in such endeavours. Decision-taking verticality in Greece is not conditioned by the particularities of local circumstances, it corresponds to the rules and structures of the national administrative framework, mitigating the restructuring impact of EU urban programmes. In this perspective, the upgraded role entrusted to cities in the current structural fund programming period (2007-2013) has to be looked at in more detail.

Although a clear policy plan regarding urban areas was not available at the time of writing, the approach to cities presented in the National Strategic Reference Framework is challenging and innovative. The relevant document recognises urban social exclusion and unordered expansion as key socio-spatial problems in the country, while simultaneously portraying cities as engines of economic activity. Continuing, it categorises and ranks urban areas on the basis of a number of criteria14, to propose, in return, 17 cities as national growth nodes. It is around these cities that sustainable development targets are to be promoted in the current programming period (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2006). The incorporation of cities in a national spatial development perspective was not attempted in the past. That development alone stands as evidence of the upgraded importance of urban areas in Greek spatial planning. The spheres of activity that comprise the emerging national urban policy agenda revolve around the familiar ESDP (European Spatial Development Perspective) concepts of polycentrism, and urban-rural partnership, while equal attention is placed on the intra-urban environmental and socio-economic issues. What is not discussed in the NSRF documents, however, is the precise role that the local political level will be entrusted with in such an attempt. ESDP umbrella terms do not safeguard the active involvement of the local level in spatial policy, nor do they recognise the relational particularity of local governance. More importantly, by bridging different territorial and political-administrative levels, ESDP priorities re-engage national planning authorities in local development schemes. Unless the role of national authorities is circumscribed, this move risks mitigating the unsettling impact of looser initiatives like URBAN, which managed to mobilise the local level toward a more dynamic and territorially specific development track.

References

Asprogerakas, E. (2004), The service sector as an inter-urban competition field: the role of medium-sized cities. Geographies, 8, pp. 50-66.

Andrikopoulou, E., Getimis, P., and Kafkalas, G. (1992), Local structures and spatial policies in Greece. In G. Garofoli (ed.), Endogenous Development and Southern Europe, Avebury, Aldershot, pp. 213-221.

Berg, L. V. D., Drewett, R., Klaassen, L. K., Rossi, A. and Vijverberg, C. H. T. (1982), Urban Europe: A Study of Growth and Decline, Oxford, Pergamon Press.

Camagni, R. (2002), On the concept of territorial competitiveness: sound or misleading?. Urban Studies, 39(13), pp. 2395-2411.

CEC (1992a), Treaty on European Union, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC (1992b), Urbanisation and the Functions of Cities in the European Community, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC (1993a), Growth, Competitiveness, Employment. The Challenges and Ways Forward into the 21st Century White Paper, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC (1993b), Community Structural Funds 1994-99, Revised Regulations and Comments, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC (1994a), Uruguay Round Implementing Legislation, Brussels, COM(94) 414 final.

CEC (1994b), Competitiveness and Cohesion: Trends in the Regions. Fifth Periodic Report on the Social and Economic Situation and Development of the Regions in the Community, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

CEC (1994c), Community Initiative Concerning Urban Areas (URBAN), Brussels, COM(94) 61 final/2.

CEC (1997), Towards an Urban Agenda in the European Union, Brussels, COM(97) 197 final.

CEC (1998a), INFOREGIO NEWS: URBAN - Restoring Hope in Deprived Neighbourhoods, Fact Sheet, (15-11-1998 EN), Brussels.

CEC (1998b), Eurocities Seminar: Agenda 2000 and the Role of Cities, Draft Speech for Mr. C. Trojan, Secretary General of the European Commission, 26-05-98, European Parliament Building.

CEC (2006a), Cohesion Policy and Cities: The Urban Contribution to Growth and Jobs in the Regions, Brussels, COM(2006) 385 final.

CEC (2006b), Regulation (EC) No 1080/2006 on the European Regional Development Fund. Official Journal of the EU, 31.7.2006.

CEC (2007), Cohesion Policy 2007-13. National Strategic Reference Frameworks, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Cheshire, P. C. (1995), A new phase of urban development in Western Europe? The evidence for the 1980s. Urban Studies, 32(7), pp. 1045-1063.

Cheshire, P. C. (2006), Resurgent cities, urban myths and policy hubris: What we need to know. Urban Studies, 43(8), pp. 1231-1246.

Chlepas, N. (1997), Local Government in Greece, Athens, Sakkoulas.

Chorianopoulos, I. (2008), Institutional responses to EU challenges: attempting to articulate a local regulatory scale in Greece. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(2), pp. 324-343.

Council of Europe, (1994), Definition and limits of the principle of subsidiarity. Study Series: Local and Regional Authorities in Europe, Report No. 55, Strasbourg, Council of Europe Press.

Council of Europe (2001), Structure and Operation of Local and Regional Democracy: Greece, Strasbourg, Council of Europe Publishing.

Datar (2003), Les villes Européennes: analyse comparative, Montpellier, DATAR.

Development Corporation of Piraeus Municipalities (1997), Introduction for URBAN – Information, Piraeus, ANDIP.

Espon (2006), Territory Matters for Competitiveness and Cohesion. Facets of Regional Diversity and Potentials in Europe. ESPON Synthesis Report III, Luxembourg, ESPON.

Hudson, R., and Lewis, J. R. (1984), Capital accumulation: the industrialisation of Southern Europe. In A. M. Williams (ed.), Southern Europe Transformed: Political and Economic Change in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, London, Harper and Row Publishers, pp. 179-207.

Iraklion URBAN II (2001), Community Initiative URBAN II: Programme Iraklion. Economic and Social Regeneration of the Deteriorated Areas of the Western Iraklion Coast (Crete) 2001-2006, Iraklion, Municipality of Iraklion.

Ioakimidis, P. C. (1984), Greece: from military dictatorship to Socialism. In A. M. Williams (ed.), Southern Europe Transformed: Political and Economic Change in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, London, Harper and Row Publishers, pp. 33-60.

Keratsini-Drapetsona (1996), Community Initiative URBAN, Piraeus, ANDIP.

Lalenis, K. and Liogkas, V. (2002), Reforming local administration in Greece to achieve decentralisation and effective space management: the failure of good intentions. In Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Discussion Paper, 8.18, pp. 423-446.

Leontidou, L. (1990), The Mediterranean City in Transition: Social Change and Urban Development, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Local Authorities Institute (2006), Urban Planning: Implementation Problems and Reform Proposals, Athens, LAI.

Louri, H. (1988), Urban growth and productivity: the case of Greece. Urban Studies, 25, pp. 433-438.

Ministry of Economy and Finance (2006), National Strategic Reference Framework 2007-2013, Athens, MEF.

Ministry of Environment and Planning (1995), Community Initiative URBAN: Structure and Organisation, Athens, MIP.

Ministry of Environment and Planning (1996), Action Plan of the URBAN Sub-programme of Keratsini-Drapetsona, Athens, MIP.

Monitoring Committee of Greece-URBAN (1995), Resolution of the First Meeting of the Monitoring Committee of Greece-URBAN, Date: 04/12/1995. Athens, MIP.

OECD (2007), OECD in Figures, Paris, OECD publications.

Petrakos, G. and Psycharis, I. (2004), Regional Development in Greece, Athens, Kritiki.

Storper, M., and Manville, M. (2006), Behaviour, preferences and cities: urban theory and urban resurgence. Urban Studies, 43(8), pp. 1247–1274. [ Links ]

Tsoukalas, K. (1986), Employment and employees in the capital: opaqueness, questions and suggestions. In A. Manesis and K. Vergopoulos (eds.), Greece in Evolution, Athens, Exantas, pp. 163-240.

UN (2009), World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanisation Prospects: The 2007 Revision, Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, http://esa.un.org/unup, (Accessed: Wednesday, August 19, 2009; 4:38:22 AM).

Williams, A. M. (1984), Southern Europe Transformed: Political and Economic Change in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, London, Harper and Row.

World Bank (1984), World Development Report: 1984, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

List of interviewees:

Iggliz, V. (18-04-1997), Member of the administration of the Drapetsona municipality. Co-ordinator of the Piraeus sub-programme of URBAN Greece on behalf of the municipality.

Iniotaki, H. (01-10-2004), Chief Executive, Iraklion Development Corporation, Brussels Office.

Katharakis, M. (12/04/2006), Chairman of the Centres for Vocational Training organisation of Iraklion Chamber of Commerce. Member of the URBAN Monitoring Committee.

Kokori, H. (15/07/2004), Chief Executive of the Department of Social Policy. Iraklion municipality.

Manola, K. (16-07-2004), Chief Executive of Hellas URBAN Administrative Unit. Ministry of Environment, Planning and Public Works.

Tsaousis, K. (24-04-1997), Financial administrator of the Development Corporation of the Drapetsona-Keratsini municipalities. Senior Manager of Piraeus URBAN.

Notes

1 As illustrated by shares in export markets in general, but also from research and technical development and innovation exports and development of new products (CEC, 1993a, p. 9).

2 As indicated by the White Paper it is the local level at which all the ingredients of political action blend together more successfully (CEC, 1993a, p. 9).

3 The extent of the motorway network, for instance, was less than 10 per cent of the Community average. In terms of workforce qualification levels, the rate of adults who had not completed education beyond primary school level was one in every two as opposed to the one in five average across the Community, while the country had only 20-25 per cent of the Communitys average of persons employed in Research and Technology Development (RTD) (CEC, 1994b, pp. 10-11).

4 The subsidiarity principle extends also to the sub-state level aiming to prevent sub-state centralisation (Council of Europe, 1994, p. 29). It is this interpretation of the subsidiarity principle that is most relevant to the attempt to identify changing Community priorities in the field of spatial policies.

5 By 1980, 57 per cent of the urban population was living in Athens (CEC, 1992b, pp. 62 and 67). The concentration of urban growth in predominantly one urban centre is an indication of the absence of localisation economies either based on firm specialisation or determined by the presence of raw material resources influencing industrialisation (see Louri, 1988, p. 434).

6 Average annual growth of Greek GNP Per Capita for the 1960-1980 period was between 4-6 per cent, the highest amongst OECD members with the exception of Japan (Williams, 1984, p. 8).

7 It is for this reason that the experience of Greek cities did not inform the de-industrialisation debate that dominated urban geography discussions in the 1980s. Greek inner cities were not part of this trend.

8 By the mid-1990s, activities related to transport, storage, oil refineries, and power-stations accounted for the employment of 46 per cent of the active labour force of the area, while unemployment had reached 21 per cent of the local labour force (Keratsini-Drapetsona, 1996, pp. 5, 7 and 12).

9 Namely, Keratsini-Drapetsona, Volos, Syros, Patra, Peristeri, and Thessaloniki.

10 Specifically, the Ministry of Environment and Planning and the Ministry of National Economy.

11 Iraklion is member of the Eurocities and Eurotowns local authority networks, and participates in the respective Knowledge Society and Capture ICT projects.

12 The cities of Iraklion, Perama, and Komotini.

13 Key examples include the local Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Association of Trade Unions, the University, and the local residents group.

14 Urban category criteria are related to: population size and dynamics; economic performance and relevance of particular sectors to local economy; location with respect to major transport routes; presence of research facilities and administrative headquarters; and, degree of functional networking linkages with neighbouring cities, amongst others (Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2006, p. 80).