Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.207 Lisboa abr. 2013

Life-trajectory and identity in the cases of Helena Almeida and Jorge Molder1

Trajetórias de vida e identidade em Helena Almeida e Jorge Molder

Anabela Pereira*

*CIES, ISCTE-IUL. E-mail: belacp@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to enhance the role of the practices of self-representation in Helena Almeida and Jorge Molder as a constituent of artists identity construction processes using a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). It also emphasizes the idea of self-representation as the result of their embodied experiences as well as of the forms of acknowledgment and legitimization of their names.

Keywords: life-trajectory; self-representation; identity; MCA.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste artigo é evidenciar o papel das práticas de autorrepresentação nas trajetórias de Helena Almeida e Jorge Molder como integrantes dos seus processos de construção da identidade utilizando uma Análise de Correspondências Múltiplas (ACM). Pretende-se ainda realçar a ideia da autorrepresentação como produto da experiência incorporada, bem como das formas de reconhecimento e legitimação dos seus nomes.

Palavras-chave: trajetórias de vida; autorrepresentação; identidade; ACM.

INTRODUCTION

Seeking to explain the mechanisms mediating the use of the body in artistic work and its implications as a social place for the name of the artist and authenticity of his work, the present study analyzes the cases of Helena Almeida (HA) and Jorge Molder (JM) through a reconstruction of their activities. These artists concentrate their practices on cultural, aesthetic, and identity resources, using the body-image in photography and occasionally in other media such as video or installations, manifesting via specific forms of self-representation their individuality and creativity. Discourses declared (by the authors and about the authors) favor a less orthodox reading of the works by denying self-identification, using instead abstract schemes of interpretation and subjectivity evoked by the body as object of artistic expression.

These discourses assume, for each case, the singularity typical of both the artist and the work, translated in the individual organization of differentiated habitus under the form of dissimilarities between the self and the body in representations, exhibited during the years, in various places throughout the artists careers.

I propose here a life-trajectory, qualitative, longitudinal, and exploratory methodology, based on the artists curricula data, through a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) characterizing and interpreting the relationships between the variables framing the multidimensional space for artists personal and professional achievement, allowing us to trace the longitudinal segments of their life-trajectories.

This process requires knowledge of the artists life and work, whose reconstruction demands a reflection on the artists conditions of integration and affirmation in the field, since during his (professional) trajectory, the artist wants above all to conquer a social place for his name and the aesthetic and artistic recognition of his work as well. This process enables us to discuss, in each cases own singularity, the relationship between the body, the self, and identity.

OBJECT AND ITS CHOICE

The study of identity, self-image, and representation templates approached by contemporary art demands a broad knowledge of literature, since it is linked to physical, intellectual, and instrumental skills that vary according to the genre, the epoch, the artist, and his own style. To the study also addresses the individual dispositions, habitus, and embodiment characterized by a being-in-the-world, indicating the immediate sense of body experience doubly translated in the existence of an historically informed sensorial world temporary presence, and in the existence of an a priori pre-objective reservoir of knowledge i.e., the self and the culturally situated body, which entails the incorporation of standards, values, ideas, and at the same time their excorporation manifested in the interaction and in the uses made of the body (Csordas, 1994). The ways of representing the body are therefore considered as excorporating practices, since they are one of the uses artists can make of their bodies, as they combine thoughts, concepts, and individual knowledge in their creativity.

The body symbolizes the intersection between the individual and society. It is the point through which the relationship between the self and the categories of the other can be explored and debated. The meaning of the self is constructed at a daily lifes pragmatic level because the person and his appearance are not only the product of societys daily circumstances, but also the results of the individual determination.

Very often these ways of representing the body that experiment with forms of personal representation through the participation of the subjects in different contexts are a result of the lived experience influence whose involvement can be emotional, intellectual, or instrumental. These approaches inscribe not only the work but also the subjects of those works in the space of contemporary art. These practices challenge standard political ideas via their expressivity, interpreting questions of subcultures or marginal societies, calling attention to daily problems, making visible the invisible through the artists body, mainly in performance (e.g., Kira OReilly, Marina Abramovic, Franko B., Yasumasa Morimura, Regina Galindo), but also in video, photography, and happenings (like Vanessa Beecroft, Allan Kaprow or the project Bloody Mess, 2004, from the group Forced Entertainment (OReilly, 2009, pp. 62-63))2.

The representations of the body in the cases of HA and JM are inscribed in these categories, however they do not intend to express a political vision of a particular subject, but to present a critical perspective, in the reflexive sense, about the arts and their limits, using the body as medium.

Thus, the self is the bond through which the relationship with nature and technology is emphasized, in experiments in which artists very often challenge their own limits in a subjective way. Nevertheless, the person is inseparable from the space and the time she lives in; is not due only to cultural standards imposed by the body in myriad ways (by diets, working out, certain beauty or fashion standards, behavioral patterns; OReilly, 2009), but also because it reflexively interrelates with itself and with the atmosphere he is inserted in. Hence, the body is the lived incorporation of societys pressures, expectations and needs. Thus, adopting self-image management or excorporation practices can be a means of protest or continuity, of affirmation or signification, of personal and professional achievement, or even interpretation of oneself and of the life experiences.

Therefore, the choice of these cases was made not only because they inscribe the body in the space of contemporary art, but because the representativeness and the specificity of the works, of international dimension, is significant in understanding the construction of the trajectory of the artists life. Both artists had different, but significant, roles in the development and structuring of the field of art in Portugal, contributing to the reflection on the differences between self-representation and the self-portrait in the arts.

Breaking the limits of painting with an exclusive artistic trajectory3, Helena Almeida (1934-) had a crucial role in creating almost a new genre in the undersized field of Portuguese art in the 1970s, in which she transcends orthodox standards and disciplines, initiating new processes of making art, leading photography, drawing, and painting practices to another level:

There is in Helena Almeida an evident archeology of painting. Thus, in many series of photos and pictures (in the 70s: works or series such as Inhabited Canvas (1976), Inhabited Drawing (1975) and Inhabited Painting (1976) the author tends to approach more of the structural elements of visual language (point, line, plane, gesture, color, space, etc.) than from what they can offer as a finished painting [Vidal, 2009, n.p.].

Jorge Molder (1947-), too, had a fundamental importance in structuring visuality in the 1980s in Portugal, making his work as critical as creative to the world of photography, and thus to the arts. His unparalleled path, not exclusively artistic4, is noticeably recognized and significant as their ideas are unequally exposed in the works:

Jorge Molders work uses all the artistic devices of classical photography: composition, subtle nuancing of black and white [and color], use of intense light and shadow, recording the intensity of an atmosphere or capturing a poetic moment. But before these are given artistic expression they are first images in artists mind. The series and their titles pursue an idea, a vision; nothing is in there by chance or coincidence [Bergmann, 1999, p. 35].

In the construction of their professional trajectories and reflecting on their own work, Helena Almeida and Jorge Molder add different social experiences of subjectivity, especially of their own bodies, consenting unevenly the propensity for individual singularity. Thus, its choice is necessary, not by the classic calling of the methodology for the universal, but from the necessity to find parameters for one sociological path of these specific artists, a model theoretically sensible to the problem of the singularity of the artist which for this object was imposed with his high level of empirical evidence (Conde, 1993, p. 200).

LIFE TRAJECTORY AND IDENTITY

Lifes trajectories are a scientific construction possessing a direct relationship with the chronological lifes sequence of the individuals.5 The trajectory points to a course or life courses for various moments in the artists lives that contemplate change in their professional, and status lives, mobility (and permanence) inside the world of art. Therefore, trajectories are considered as constructions of communicative action among cognitive subjects (Giddens, 2000) that are performed in the world of art according to an assured identification. Furthermore, they can be accurately reconstructed through the presented model since it allows for the reconstruction of their stories (namely related to courses of exposure, internationalization maps, and recognition storyline) and at the same time to unveil their personal and social identification translated in self-representations, discourses, and styles, allowing in turn to understand its implications and meanings.

Thus, the development of a planned strategy for a life, personal or professional project, implies the prosecution of a certain trajectory. It is the result of the development of intentions, attitudes, practices, technique and knowledge, habitus and embodiment, whose goal is the construction and reproduction of the work of art and artists social world generally and particularly in their daily relationship with that same world: the trajectory of an artist is a process of individuation corresponding to different degrees of individualization, in dissimilar lifes horizons, and correlatively the forms of personal identity vary according with the social places in which they are inscribed (Conde, 1993, p. 202).

To plan the trajectory of the artist means to deliver him to the frame of his subjectivitys social experience, i.e., to refund the artist in the field as a specific domain of reference practices for a personal and social identity, the plan in which his different degrees of individualization: condition, protagonist, and trajectory are inscribed, besides adding several lifes dimensions, namely knowledge, the experience and the project. For this reason, the trajectory is the solution of the synthesis between the projection of the trajectory and lifes dimensions. In the cases of artists, the perspective of the trajectory of life also comprehends the identification of the conditions given by the singularity of the habitus indicating that they are in social positions allowing to consent or to force the relation to life, whether in the perspective of a personal possession, as in the self-expressive discourse perspective (Conde, 1993, p. 203) as the images turn out to be.

Identity expresses, then, a certain adherence of the self to the being, since the existence of the living body is intrinsically linked to the experience of the lived body. Accordingly, the perception of the body, the incorporation of norms, values, and knowledge influence the construction of the self as a project and as a quest for the definition of an identity that although mutable, has a permanent character. Self-image as an expression of a possessed self-consciousness allows the evaluation of this duplicity.

Nevertheless, this acknowledgement does not lead to the rejection of the distinction between Ricoeurs (1990) idem and ipse. On the one hand, the action can always be distinguished from its agent, allowing the distinction between the work and the subjects work; on the other hand, there is a dialectic between ipseity or unstoppable change of time and sameness or time permanence (Ricoeur, 1990), defining the personal identity.6 These allow a double reference to the body as an entity (my body) and, on the other hand, as an ontology or identity (I am a body) (Le Breton, 1992).

Several duplicities are here detectable: first, we are in the presence of interpretations of the self in its complexity and deepness, the body as a medium and as a metaphor to explain the distance between the body as lived reality but also as image; second, between the image in the optic domain and image in the self-domain (self-image).7

In short, the self-multiplication of the artist in several figures or representations of himself is a two-way interpretation: the repeated image of a unique individual or the representation of a persons (re)duplication. In other words, we consider the image as a pictorial representation of the impossibility of personal selfs unity (figuration) or consider it as an expression of a certain experience (fiction). The point is that while figurative representation of the body tends to lie in the dimension of the optic, those representations involving the dimension of the experience of the body concern the sense and the experience of inhabiting a body, rather than just with the experience of looking (i.e., the gaze).

Thus, the constant reconfigurations of the subject in the work are a result of this inter-relation established between the self and the social world, and between the dispositions and the practice, more specifically, the result of the direct experience of the body existence reflected in a certain time and space given by the understanding of the body in its relationship with the cultural activitys domain. This is based on the pre-sensed and undetermined relation in intuition or existences sensitivity sense, where the practice includes the body experience and self-representation as discursive practice, in which identity as a self-reflexive project is both the result of that experience and the result of its daily reconstruction.

Not only does this process allow the reconstruction of artists (personal and professional) life-trajectories but also doing an analysis of the forms of signification of the body as a discourse established and legitimized through its changeableness8, and conveyed by means of its various versions of adopted bodily image in the self-images constituted as the subject in the work. In short, it is the result of the characteristics of his work and the way the artist uses acknowledgment and rules that regulate the art world; it is also constructed in the autonomous sense of his own work in relation to himself. The style, the mark, the look for the place of the name, and of the work, as a reality that does not subvert the rules and the delimitations of the artistic field, present in the practices and in the discourses about the practices, as well as in the evidence of this representative use of the body as self-representation, visually enunciating its authenticity as a work of art.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

In order to group and classify the information in artists curricula, a database was built using the SPSS software containing all data taken from those curricula: biographical information, expository courses including lists of individual and group exhibitions in Portugal and abroad through the years, and the spaces where they occurred.

The variables created are therefore limited to the information available in this source. By the substantive characteristics of information, especially qualitative, some variables were then transformed into metrics in order to perform an MCA, whose goal is the identification of the profiles or associations between the categories of the variables that are part of the analysis.

The data pertain to both cases, JM and HA, whose artistic courses reside between the 1970s and the present. Exhibitions and other events in which the artists engaged from the beginning of their careers (1961–HA; 1977–JM) until the end of 2009 are gathered into the data analyzed.

INDICATORS EMPLOYED

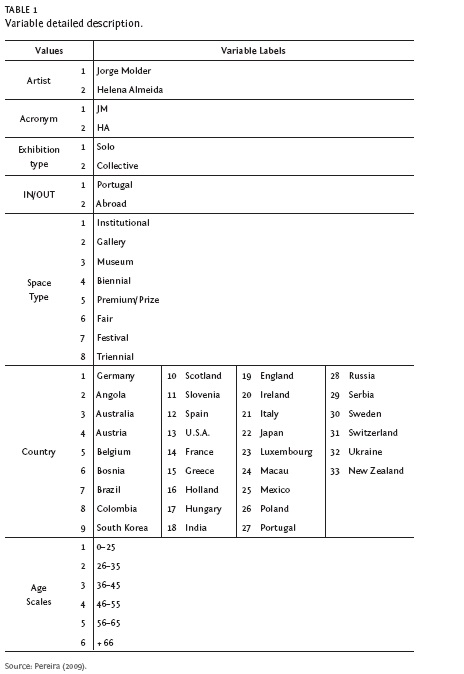

In order to measure, comprehend, and clarify aspects of the life and work of the artists, a number of indicators were used (Table 1). These were grouped into several specific classifications (categories) that intend to be an essential contribution to a wider knowledge on these individuals.

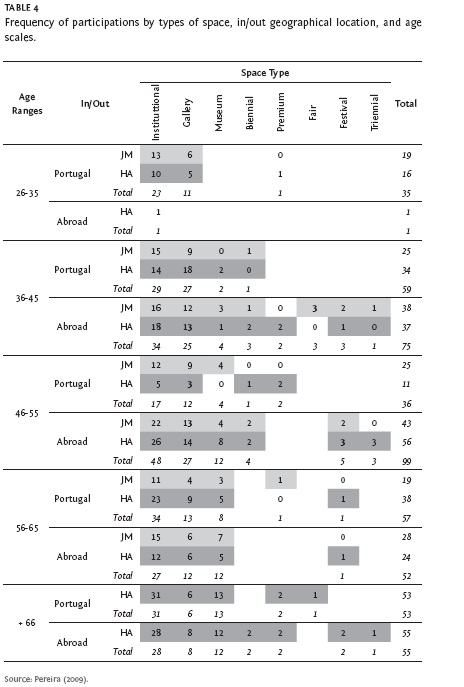

In order to complete this analysis, it was necessary to consider several steps, first, the diverse spaces in which exhibitions normally take place. Eight categories of types of spaces were created: the institutional (a generic category including Modern Art Centers, Photography Centers, and other institutions very often recognized by the public in general, but that are not exclusively places for art, such as banks, foundations, and archives) followed by seven categories of spaces that are exactly what their names indicate, galleries, museums, biennials, awards, fairs, festivals, and triennials.

Every country is part of the geographic location recording the artists internationalization. The presence of both artists was identified in 33 countries. The age ranges category identifies the periods of greater or lesser exhibition activity. Two very important typological categories were solo and group exhibitions, under the designation of types of exhibitions.

ANNUAL PARTICIPATIONS IN EXHIBITIONS AND OTHER EVENTS

– CHRONOLOGICAL LINE

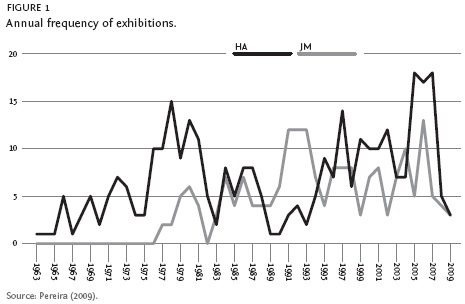

Overall, there were 325 participations in exhibitions and other events in the case of Helena Almeida, and 197 in the case of Jorge Molder during the period analyzed. JM is approximately ten years younger than HA, and this may partially explain this difference, since the courses are in terms of internationalization and exhibitions spaces, taking into account the study of the variable organization of the exhibition, which is similar in both cases.

The distribution of participations in annual exhibitions and other events (Figure 1) is relatively homogeneous (with regular, constant activity over the years) for both artists, registering higher values in 2007 in Molders case, the year after he won the juried IAAC Award. He went through a period of greater notice from the mid- to late 1990s, due to the fact that he represented Portugal at the Biennials of S. Paulo in 1994 and Venice in 1999, which in turn stimulated the activity in the following years. In Almeidas case, one of the strongest activity periods is from 2005 to 2009, presumably spurred by her Portuguese representation in the 51st Venice Biennial in 2005 with the series Intus.

The incidence of participation in more recent years can be explained by the greater complexity of the market itself, greater visibility of the artists and networks linking them to culture and the art world, their media disclosure, and their wider exhibition trajectories in this moment of life, potentiated by the individual path of the artists, and by the profile gained through time.

The effect of the participation in the Venice Biennial is also evident in the cases of these artists. This is one of the greatest moments of the artists personal and symbolic consecration, indicating an expansion of the network of relationships and cooperation between artists and the world of art in which they function.9

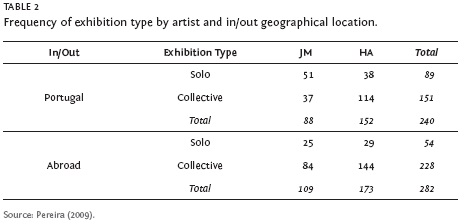

PARTICIPATION IN GROUP AND SOLO EXHIBITIONS

INSIDE AND OUTSIDE THE COUNTRY OF ORIGIN

Despite the fact that participation in group exhibitions inside and outside their home country (Table 2) is less than half the number of individual exhibitions (379/143), it is noteworthy that the artist with fewer exhibitions, JM (197 group and solo exhibitions at home and abroad), has more solo exhibitions in Portugal (51) when compared to HA (38 solo exhibitions at home; 325 in total). These differences express changes in the market itself and in the structure of the field that took place in the ten years of age that separate them; differences that reflect personal choices which are in turn influenced by the artists own individual identities, and by the characteristics of the work, and also by the conditions and positions they occupy within and outside the field. It is worth noting that HA has an entirely artistic path, while JM had several professional responsibilities both within (as Director of CAMJAP10 from 1994 to 2009) and without the field of art (for instance, as Director of the Service of Education of the General Directorate of Prison Services, of the Portuguese Ministry of Justice between 1976 and 1990). From 1990-1994 he was performing functions in CAMJAP, but as assistant to the previous director, the architect Sommer Ribeiro. These specificities of the artists professional trajectories are important in explaining the differences in terms of the overall participation in exhibitions and other events between the two artists.

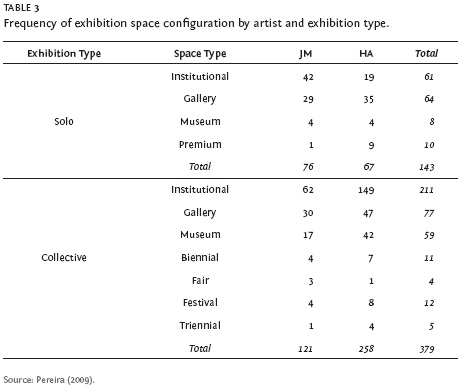

DISTRIBUTION OF PARTICIPATIONS BY DIFFERENT SPACE TYPES

Concerning exhibitions space types (Table 3), the most used spaces by the artists are the institutional ones. It is important to note that this space type gathers several designations in terms of spaces (hence the greater number of occurrences). On the other hand, they are spaces of elevated institutional fame, and consequently very sought after by artists. Galleries, the space par excellence of art, is the second place of choices/opportunities.11 After a certain period of activities in the artistic cycle, the artists are represented in specific galleries not only in Portugal but also abroad, and sometimes in exclusive ones, hence, the repetition of exhibitions in different years in the same places. The list of occurrences continues with museums and the participation in the biennials followed by the exceptional events in terms of occurrences such as awards, fairs, and festivals. The rarer triennials, as the name indicates, figure last, only once for JM and four times for HA (one time participation in Angola and three in India).12

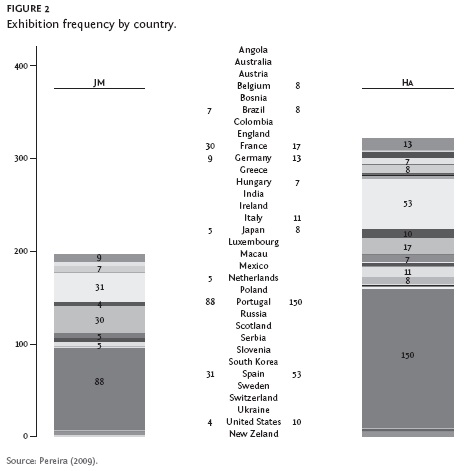

PARTICIPATIONS DISTRIBUTION BY COUNTRIES

-In the distribution of exhibitions by countries (Figure 2), Portugal appears first, followed by Spain, France, and Germany in both artists cases, although with a different number of participations in each of them. Then, and despite fewer participations when compared with the previous ones, the artists follow similar courses, visiting the USA and the eastern European countries, such as Hungary and Slovenia. Thereafter, the course changes, presenting very disperse data when both artists are compared. The Portuguese-speaking countries are scarcely represented, only Brazil appears with some importance. Angola is also part of the internationalization map, but only for HA, with two participations.

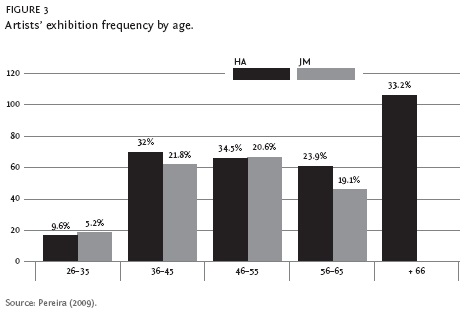

PARTICIPATIONS DISTRIBUTION BY AGE – DIACHRONICAL LINE

Looking at Figure 3, there were periods of greater activity in the ages 36-45 and 46-55 for both artists, and for HA the peak of exhibitions participation occurs at the age of +66. These periods coincide with the data in Figure 1 (chronology).

Finally, examining the variables age in interval scale, in/out geographical location by artist (looking at total values), and the exhibition spaces (Table 4), we see how exposition periods are developed and the way they change, with activity increasing from the range 26-35 up to the next, from Portugal to abroad, from the most generic to the most specific categories of spaces, with the artist being highly distinguished around the middle careers, and presenting constant and regular activity indexes in the last years.

DELIMITATION AND PROPOSAL

OF A MULTIPLE CORRESPONDENCE ANALYSIS (MCA)

In order to perform the MCA13 after the selection of the group of indicators, there was a rehearsal of several solutions of aggregation, quantification and interpretation of categories whose present final result allowed the multidimensional characterization of the structured space of the artists personal and professional achievement. From the characteristics of the available information there are no missing cases included in the analysis, having considered all cases/objects (N=522). In order to favor the structure of the curricula, indicators that better translate that structure have been used.

The interpretation of relationships underlying this group of indicators and their respective categories have allowed us to identify two analytical dimensions, or the two structuring lines that guide the organization of the artistic course – space and time (along with typology of exhibition, lines that also define the organization of exhibitions in the respective curricula). Indicators used in this analysis were: configuration of exhibitions space (eight categories), geographical location by country (thirty-three categories), age ranges (five categories), and exhibitions type (two categories).

STRUCTURAL AXES OF THE SPACE FOR PERSONAL

AND PROFESSIONAL ACHIEVEMENT

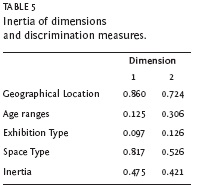

The exercise suggests two structuring axes of this multidimensional space or two dimensions indicated by the histogram. These dimensions recognize the main structuring axes of this topographical space. The first dimension is the most important, although the second, which is less representative than the first, is even substantially richer.

Looking at Table 5, we see that the first dimension(Space-geographical) is the most expressive one in analytical terms (inertia=0.475), followed by the second Diachronic dimension, (inertia=0.421)14. The internal consistency of each dimension is relatively good in the first dimension (α=0.631), and reasonable in the second (α=0.541). These are adequate values because they do not imply very high values for the Cronbach alpha, given that it is expected for the analytical dimensions to be distinct (Carvalho, 2008).

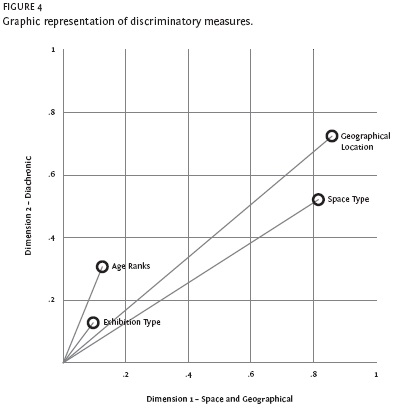

Based on one of the dimensions already emphasized by inertia, the variables whose discriminatory measures are at least identical to that inertia threshold must be favored in each of the respective dimensions, so as to afterwards identify the most structuring space axis in the analysis (Carvalho, 2008, p. 79). Thus, the analysis of the discrimination measures (also in Table 5) of the variables and their categories contributions15, proved to be appropriate after the projection of the first and second plans (Figure 4), despite the few variables included. It is possible to distinguish these two structural axes of the space in the analysis suggested by MCA.

Hence, geographical location and type of spaces are more discriminating in the first dimension − Space-geographical dimension − establishing a differentiation by country and by the configuration of the different exhibition types of spaces (galleries, museums, other institutional spaces, awards, fairs, biennials, triennials, and festivals).

The age ranges and exhibition type defines the second dimension − Diachronic dimension − and discriminates categories according to the disposition of the exhibitions given by the diachronic time of the subjects, and to the typological character of group and solo exhibitions.

MOMENTS OF DISTINCTION IN THE TRAJECTORY OF THE ARTISTS

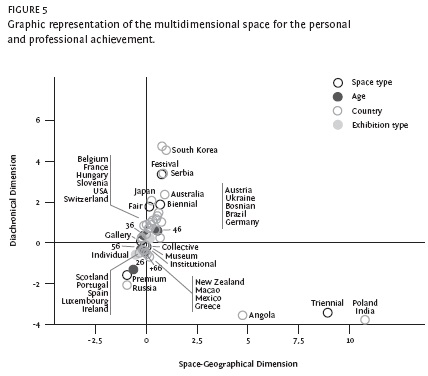

In order to determine the positions and identify the main associations established among the categories it is possible to observe its projection in the multidimensional plan for artists personal and professional achievement (Figure 5). Despite the strong proximity of categories around the graphs origin, objects represented possess certain bonds among them for sharing common characteristics, certain specificities that differentiate them from some and being closer to others, grouping them distinctively in this multidimensional space.

Graphically, we see that despite this logic there is a strong proximity of the categories that are distributed evenly around the origin, preventing the identification of very different profiles of the objects according to these categories. This is due to the large number of categories that the geographical location must discriminate. However, although these characteristics are not highly distinctive objects, they are still indicative of the most distinct moments of the lives of the artists, important for the reconstruction of social and symbolic contexts that guide and organize their professional course.

It is therefore possible to recognize three moments characterizing the personal and professional trajectories of the artists: first, a segment of greater individualization of the artists trajectories, indicated by the proximity of the categories Portugal, Galleries, individual, 26, and awards, met in the 3rd quadrant of the plan, which has to do with the peak of the demand of affirmation and integration in the field in the early career; the category 36 in the 2nd quadrant, adjacent to the previous categories and to the category 46, in the 1st quadrant corresponds to the moment of their careers that distinguishes recognition of their singularity through the participation in major events, noted for its proximity to the categories biennials, art fairs, and festivals, as well as the expansion of the artists internationalization in several countries (e.g. United States, Japan, Italy, Australia). This moment is when the artists reaffirm themselves in the field, with those categories appearing relatively close to the institutional spaces.

Finally, the strong proximity of the categories Collective, Museums, Institutional, and categories of higher age, 56 and +66 near the origin (in green) corresponds to the moment of greater institutionalization of the artists. The patch of dots indicates a greater number of occurrences, pointing to a strong expansion in activities during the middle-advanced career phases.16

DISCUSSION

The singularity of habitus allows putting into an equation life dimensions (knowledge, experiences and projects) and a narrative perspective (allowing tracing artists trajectories), placing the subjects in a multidimensional space for personal and social identity construction processes, defined by the variables contained in the curricula.

This analysis allows differentiating the segments of the artists lives in a longitudinal narrative perspective of careers – life stories related with their exhibitions courses, identifying the two main lines structuring the curricula of an artist: space and time.

This perspective calls for a consideration of other life dimensions such as biographical conditions, protagonism, and paths (e.g., social and cultural settings). These factors that arise from the singularity of the proper cases are inherently related to the artists identity and how it is constructed. At this level, the trajectories between the artists assume different aspects since biographical, cultural, and reflexive characteristics of identity influence approaches of the body in a different way in their work.

HAs exclusive artistic trajectory is influenced by her biographical conditions predisposing her connection with the arts, namely the relationship with sculpture inherited from her fathers background, clearly influencing her choices with respect to the processes of how she makes, looks, and perhaps feels toward it. In her approaches of the body she always expresses the will to explore her own physical limits, since the days when she posed as a model for her father. Evidently, those experiences shape her work, and she becomes a model for herself. In fact, she expresses the desire to become the work (evident in the first works where she dresses the canvas, or even as suggested in the several titles, i.e. Inhabited). For these reasons, in the work of Helena Almeida boundaries of disciplines were transposed since the beginning, as she felt the need to break away from painting, mixing the different genres and techniques.

At the external level, the artistic context also influenced her work, for instance with respect to performance practices arising in the 1960s, with direct connection with the arts of the body (body art). She states: ( ) I think my main influences arise from the field of performance and installations; as for photography practices, I think it was also important to know the work of other artists of my time which became interested in photography. It was my time; I used a medium of my time (Helena Almeida, 2000, apud, Mah, 2000).

Finally, other aspects influencing HAs trajectory come from proposals, in which themes emerge, and later lead to other works, as is the case of the video-work A experiência do Lugar II (2004), which symbolizes at the same time one affective experience of the artist in relation with her atelier. In fact the space is a physically powerful component of her work:

The atelier is both my body and a working material such as pencils and ink. The atelier exists as if it were my own body [and] ( ) I hope that in this body is contained all the painting. All painting has to go through my body ( ) the presence of the real body is fundamental because the painting and drawing only exist when I exist as a body [Helena Almeida, 2000 apud Mah, 2000, p. 45].

These biographical, cultural, and social influences are transposed to the work through the artists embodied experiences, providing its uniqueness and singularity: I transpose to the medium my stories, my problems (Helena Almeida, apud Machado, 1996, p. 10). At the same time, the artists identity is built through this process that also involves a personal project, linked by their ideas, intentions, and personal needs. The approaches of the body in the work incorporate these reflexive and cultural identity aspects, i.e., they are unconsciously structured by the artists lived experiences, and at the same time structuring their living experiences, defining in turn the meaning and identity of the work:

The body-testimonial, with all the characteristics of the body [ ] artists daughter, artists mother, artists wife [ ] but those attributes are disappearing to be only the painting, the body of Helena, Helenas painting [Helena Almeida, 1982, n. p.].

In the meantime, statutory and narrative aspects of identity are constructed and recognized along the paths, so that they become institutionalized through it. The identity of the artist, and of the work, is thus being created and built recursively in this relational process between self and other, between artist and the world.

In the case of JM the process of identity construction is similar, but the artist has a distinct path, namely in what is related to biographical, cultural, and reflexive identity aspects: with a trajectory not solely artistic, a degree in Philosophy and being half Hungarian and half Portuguese, JM transposes in a non-linear way those influences to the works, a fact that gives them a unique character: I can say, for example, that it is not by chance that the 1990 series is called The Portuguese Dutchman. I am indeed half Portuguese and half Hungarian, with a Dutch surname; the title refers directly to events in my past or present life (Molder, 1998 apud Melo, 1998, n.p.). Actually, or by inclusion or expulsion, everything we do always marks everything that is happening in our lives (Molder, 2009, apud, Vieira, 2009, p. 15).

In his work the body is explored in a perspective of questioning the relationship between the self and the other, between the self-portrait and self-representation as Molder plays with the endless variety of images of himself, which always end up being the images of each other without ever ceasing to represent him. In this game he also plays with the paradox of life and identity: the representation is him, but always mediated by others that the picture reveals (Oliveira, 2009).

Daily experiences, inspirations, dreams, but also his characteristic pragmatic reflection are usually transposed to the works as what can be interpreted as habitus transference. As JM states about time and the interpretation of dreams (2009):

All images are very marked by images of our childhood. The images have to do with us; we have to do with us, with some continuity. The question of continuity of time is curious. We cannot find a unit with respect to time, but we find this: time does not exist, there are many times. And our memory for these times is discontinuous. When we are young, we have the idea that the time will create a thickness, and that one day we will look at the past through this thickness. The experience of the passage of time is exactly this: that thickness is discontinuous. There are things that have happened many years ago and could have been yesterday, and there are things that have happened recently and they were lost. ( ) Is all our experience configured from a principle and a sequel? I think so, and I think not. We found marks of the primordial things, which are making their reappearance. And there are things that happen in life, and people with whom we will find [Jorge Molder, 2010, apud Ribeiro, 2010, n. p.].

Uncertainty and hesitation are aspects that JM appreciates and always explores. He is interested in the material aspect of the image, questioning its immaterial essence. In the scope of that essence he positions himself playing with ideas, with otherness: self-representation as the possibility of discovering the other in him, the double, a face and a body that in a certain way is liberated from the author, which lies between the abstract and the concrete, creating in the end a sort of confusion (Oliveira, 2009).

Regarding his social and narrative identity, the weight of his other professional occupations and personal experiences is evident in his work − it is true that, as having no artistic training, I always tried to live closely with artists, and think about the problems of art with them (Molder, 2011 apud Crespo, 2011), besides benefiting also in this course of invitations and prizes. Lastly, the artist also had the influence of the art of the 1970s, as well as of the structuring of the field of art in Portugal during the 1980s, as did Helena Almeida, and which determined, in a relative way, the characteristics of the work and influenced the direction of his trajectory (as with hers), going through a similar process of individuation.

CONCLUSION

The self-representation approaches of HA and JM comprise a relational field for multiple possibilities in which the body appears both as figurative representation and as metaphor or fiction. These approaches allow reflecting on how the subjects relate themselves with the space, time, technology, the unknown, the unexpected, and the artistic sphere with society and life inscribing the singularity, the body, the self, and identity as central concepts of this analysis.

Simultaneously, the demand for the recognition traces the artists trajectories and is the measure of their personal and professional project, which happens in a certain space and time, here named as multidimensional space for personal and professional achievement, through which identity, of both the subjects and the work, is constructed. Analyzing this space, a process of individuation with three distinct moments was identified: the moment of individualization symbolizing the artists integration in the field; the moment of recognition where artists are increasingly recognized by others, and finally the moment of the institution of their names and works (representing the total embodiment of their condition as artists, the legitimation of their names and autonomy of the work).

In this perspective, life-trajectory (and identity) is thus considered as a process (constructed on the dialectical interaction between the internal and embodied dispositions of the subjects, and the external conditions of the field), and a project, since there is an intention, a purpose (e.g., recognition, legitimacy, and autonomy of the artists names and works) while developing their actions or discursive practices (e.g. the representation of the body, the use of the titles, and the reflection on individual experience subjectively translated into the scope of the work).

Singularity of habitus, being invisibly translated into the representation through the variables of incorporation (e.g., biographical, cultural, lived, and living embodied experiences) therefore has an important meaning in this process.

Frequently connected with time (Jorge Molder) and with space (Helena Almeida) or simply with the way it (the body) transforms itself into the instrument of representation, their works can refer to the way photography or video produces relativistic ambiguities in which the body appears as the basis of identity construction processes.

Hence, the role of the body in the trajectory of JM and HA emerges as the significance of the lived experience as well as the medium between the self and the other(s) based not only on self-knowledge but also on the artists relationship with the world inscribed in their excorporations practices and expressed through self-representation.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, H. (1982), Catálogo Helena Almeida, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Edição FCG. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, H. (2000), Manual de pintura e fotografia. Entrevista a Helena Almeida, por Sérgio Mah. Arte Ibérica, 40, pp. 44-48. [ Links ]

BENZECRI, J.P. (1982), Histoire et préhistoire de lanalyse des donnés, Paris, Dunod. [ Links ]

BERGMANN, B. (1999), Truth and illusion – on the work of Jorge Molder. Anatomy and Boxing, Aachen, Ludwing Forum, pp. 34-39. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. (1999 [1993]), A Miséria do Mundo, Petrópolis, Vozes. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, H. (2008), Análise Multivariada de Dados Qualitativos. Utilização da Análise de Correspondências Múltiplas com o SPSS, Lisbon, Edições Sílabo. [ Links ]

CONDE, I. (1993), Falar da vida (I). Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 14, pp. 199-222. [ Links ]

CRESPO, N. (2011), Jorge Molder em território incerto (entrevista a Jorge Molder). Público--Ípsilon, 08-06- 2011. Available at http://ipsilon.publico.pt/artes/entrevista.aspx?id=286841 [consulted 10-06-2011]. [ Links ]

CSORDAS, T.J. (1994), Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self, London, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

DUBAR, C. (2006), A Crise das Identidades. Interpretação de uma Mutação, Lisbon, Afrontamento. [ Links ]

FORNACIARI, C. (2010), Performance e direitos humanos. Discursos pela tolerância em Marina Abramovic. Comunicação apresentada no Congresso Deslocamentos na Arte/Deslocamentos Estéticos no Espaço Público (2009). Available at: http://abrestetica.org.br/deslocamentos/f06.swf [consulted 11-01-2012]. [ Links ]

GIDDENS, A. (1991), Modernidade e Identidade Pessoal, Oeiras, Celta. [ Links ]

GIDDENS, A. (2000 [1979]), Dualidade da Estrutura. Agência e Estrutura, Oeiras, Celta. [ Links ]

LE BRETON, D. (1992 [1953]), A Sociologia do Corpo, Petrópolis, Editora Vozes. [ Links ]

MACHADO, J.S. (1996), Negar a pintura. Artes e Leilões, 37, pp. 10-12. [ Links ]

MAH, S. (2000), Helena Almeida – Manual de pintura e fotografia. Arte Ibérica, 40, pp. 44-48. [ Links ]

MELO, A. (1998), An interview with Jorge Molder. Photographs (Susan Copping Curator), London, South London Gallery, n. p. [ Links ]

MOLDER, J. (1998), Photographs (Susan Copping Curator, 1998) London, South London Galery. [ Links ]

MOLDER, J. (2009), A Interpretação dos Sonhos, Lisbon, FCG. [ Links ]

MOLDER, J. (2010), Modo de usar (entrevista a Jorge Molder, por Anabela M. Ribeiro). Público-Pública, 07-02-2010, pp. 45-51. [ Links ]

MOLDER, J. (2011), Jorge Molder em território incerto (entrevista, por N. Crespo). Público- Ípsilon, 08-06-2011, Available at http://ipsilon.publico.pt/artes/entrevista.aspx?id=286841 [consulted 10-06-2011]. [ Links ]

OREILLY, S. (2009), The Body in Contemporary Art, London, Thames and Hudson. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, L.S. (2009), Jogos de prestidigitação. Público-Ípsilon, 08-10-2009. Available at http://ipsilon.publico.pt/artes/critica.aspx?id=241156 [consulted 01-11-2009]. [ Links ]

RICOEUR, P. (1990), Soi-même comme un autre, Paris, Éditions du Seuil. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, A. M. (2010), Modo de usar (entrevista a Jorge Molder). Público-Pública, 07-02-2010, pp. 45-51. [ Links ]

VIDAL, C. (2009), Helena Almeida, a obra fotográfica e os seus desenhos: um círculo fechado e perfeito. Available at http://5dias.net/2009/04/10/helena-almeida-a-obra-fotografica-e-os-seus-desenhos-um-circulo-fechado-e-perfeito/ [consulted 20-2-2010]. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, F. (2009), O aparecimento da ocultação (entrevista a Jorge Molder). Artes e Leilões, 24-12-2009, pp. 14-18. [ Links ]

Received 14-02-2011; Accepted for publication 04-06-2012.

NOTAS

1 An earlier version of this article was presented to the 2010 PSA Annual Meeting, Oakland CA, April 8-11, Revitalizing the Sociological Imagination: Individual Troubles & Social Issues in a Turbulent World. I now present a modified and enlarged version of that communication.

2 For a clear account of these practices, see OReilly (2009) and Fornaciari (2010). Although equally significant to the world of contemporary art, these approaches are not explored in the scope of this article.

3 She is daughter of the sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida and one of the main contemporary Portuguese artists. She started her career by participating in collective exhibitions in 1961; in 1967 she had her first solo exhibition; she studied painting in the Fine Arts School at the University of Lisbon.

4 He has a B.A. in Philosophy from the University of Lisbon, and began his artistic career with his first individual exhibition in 1977. Professionally, he worked for the Justice Ministry (1976-1990), where he occupied several positions. In 1990 he began working as a consultant for the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian (1994-2000), after which he was executive director of José de Azevedo Perdigão Modern Art Center – CAMJAP, which he left for personal reasons in 2009.

5 The trajectory represents a series of positions successively occupied by a same agent or group in a transformation space and subjected to incessant transformations, thus allowing to unstring from the subject and situate the biographical happenings in allocations and dislocations in the social field (Bourdieu, 1999). Hence, lifes trajectory can be considered as a part of lifes story or as a biography, a certain course, itinerary or lifes cycle, awakening the interest of the researcher such as occupational, migratory, work trajectory, etc. As theoretical, methodological categories, lifes trajectories are not ontological realities or possible abstractions. They are social historical constructions produced and reproduced from conflictive relations among structure and action, since the structures are made from social relations and in social relations, systematically developed and produced according to a complex structuration process by individuals and collectivities, part of a same space-time conjecture (Giddens, 2000).

6 Being a paradox, according to Ricoeur (1990, p. 150) this definition of personal identity can only be solved by narrative theory in a reciprocal re-edification between action and the self, between reflexivity and discursiveness in which memory, dispositions or the whole of acquired identifications, this is to say, the habitus whose sedimentation tends to be reconstructed and rediscovered in the course of the practice and in the boundary that tends to abolish the innovation that preceded it plays an important role.

7 If personal identity is not something that is simply given as a result of the continuity of the subject in the social action system but something that has to be routinely created and supported in its reflexive activities (Giddens, 1991, p. 53), then the body becomes equally socialized and drawn into the course of the daily life reflexive organization and, consequently, of the specific practice of self-representation. Thus, what is applied in the self and in the pure relations domain is equally applied to the bodys sphere, since the body image appears as one of the aspects of personal identity construction, similarly succeeding with other aspects of bodys surface (namely ways of dressing, moving or talking) whose practical insertion in daily life is an essential part to the sustenance of self-identitys coherent sense (Giddens, 1991, pp. 98-99).

8 Dubar (2006, p. 52) distinguishes the cultural and reflexive identity forms (socialized self and the acknowledgment by the significant others), and statuaries and narrative identity forms (role play and acknowledgement of the significant generalized others).

9 In the years the artists participated in this event [1999 (JM) and 2005 (HA)], there is the realization of work-videos on their lives and work such as Jorge Molders Life shown in Artes e Letras aired on RTP2 on 5.12.99 and Inhabited Painting directed by Joana Ascensão and aired on January 1st of 2006 at the Aula Magna in Lisbon. Both these works have allowed in terms of communication/disclosure another type of visibility for both the subjects and the work, due to the fact that they allowed a more unusual type of exhibition for artists given outside the art gallery. This has justly influenced their fame besides being, apart from the CV(s), additional documentary evidence for the analysis of the cases.

10 Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisboa.

11 Depending on the periods of the artists lives, these change from opportunities to personal choices. It is something that also concerns the type of relations the artists had been developing and the characteristics of their own work. According to the analysis, invitations to participate in events have a tendency to increase along the trajectory, allowing more options.

12Biennials, festivals, fairs and triennials categories are always mentioned as group participations because although often participation is an individual one, for instance when the artist is chosen due to his name or due to the singularity of his work to represent his country in a biennial, this representation is always framed in the scope of the group event. While awards are always individual because although they are very often attributed in the scope of other events, for example in festivals or biennials, or when the same award is simultaneously attributed to several artists, this is always a distinction of artists singularity and of a unique and particular character.

13 This analysis allows illustrating the matrix of positions with certain associated existence conditions socially defined with specific configurations − each position corresponding to a combination of multiple properties defined by a coordinate system. Because they are not analytically reducible among them, their analysis comes from the relation analysis established between them (Carvalho, 2008, p. 20). The goal of this analysis is to trace the main segments or moments characterizing the artists trajectories, in addition to the suggestions emerging from the initial descriptive analysis, above.

14 The inertia varies between 0 and 1 and the closer to the upper limit, the more variableness is explained by dimension (Carvalho, 2008, p. 64). Nevertheless, in the context of multiple correspondence analyses, it can occur that inertia values are relatively low, and consequently the percentages of the explained variableness are tendentiously not very high (ibid., p. 67). However, it is not because these values are low that the interpretation must cease. The reduced numerical expressiveness does not necessarily mean lack of quality of the analysis. It can occur that individual profiles lie further from the median profile. Therefore, inertia values are weak, but not necessarily less interpretable (Benzecri, 1982, p. 43 apud Carvalho 2008, p. 67).

15 For the purpose, the coordinate board and the categories contributions for each dimension can be equally helpful for a decision. It can be added in a merely indicative title in terms of explanation that 1st dimension=4.31%; 2nd dimension=3.83%; (percentages based on the inertias of each dimension/total inertia* 100). The total inertia=11 and is calculated based on the maximum number of the dimensions included in the solution, this is to say, 48 possible dimensions for this case (because there are no missing cases in this analysis r max=p-m=44, in which p=48, is the total number of categories and m=4 is the total number of variables). The medium contribution is (1/p) =1/48=0.020, also calculated based on the maximum number of dimensions in the analysis.

16 Regarding geographic location (country), Portugal and Spain are the countries with the highest frequency of exposures, for both artists. Both are located near the individual location on the one hand, in the initial phase (26 years), and near the category Collective on the other, in the most advanced career (56 years) phase. The large number of events in these countries gives this connection of categories little discriminant value, and is therefore graphically not only very close together, but also very close to the graphs origin, as seen before. The categories in the most remote end of the 4th quadrant concern Triennials, held in Angola and India, with just four hits in total, consequently presenting atypical coordinates. However, the decision to keep them in the analysis prevailed, since if they were removed, the map configuration would remain identical.