Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Análise Social

versão impressa ISSN 0003-2573

Anál. Social no.233 Lisboa dez. 2019

https://doi.org/10.31447/AS00032573.2019233.07

ARTIGOS

Evaluating and fostering transparency in local administrations

Avaliação e proteção da transparência em administrações locais

Pedro Molina Rodríguez-Navas*

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1586-881X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1586-881X

Vanessa Rodríguez Breijo**

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9749-8444

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9749-8444

*Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad, Facultad de Ciencias de la Comunicación, Autonomous University of Barcelona. Edifici I, 08193, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain. pedro.molina@uab.cat

**Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y de la Comunicación, La Laguna University. Camino La Hornera, 37 - 38200 San Cristóbal de La Laguna, S/C de Tenerife, Spain. vrbreijo@ull.edu.es

ABSTRACT

The methods used to evaluate the transparency of local administrations present notable differences that are influenced by national legislation and administrative characteristics. Consequently, it is difficult to formulate a valid international procedure to obtain a global picture. We have conducted a comparative analysis of the procedure developed by Transparency and Integrity in Portugal with that designed by the Laboratory of Journalism and Communication for Plural Citizenry in Spain. The results reveal that the approaches, maintained in various disciplines, exhibit notable but complementary differences. In the conclusions we propose new elements to design a method based on a syntax of transparency and order of fundamental elements.

Keywords: transparency; evaluation method, public communication, local administrations.

RESUMO

Os métodos utilizados para avaliar a transparência nas administrações locais apresentam notórias diferenças que são influenciadas por fatores como a legislação nacional e as características administrativas. Por conseguinte, é difícil estabelecer um procedimento internacional que se mostre válido para a obtenção de uma imagem global. Conduzimos uma análise comparativa dos procedimentos desenvolvidos pela Transparência e Integridade em Portugal, com aqueles desenvolvidos em Espanha pelo Laboratório de Jornalismo e Comunicação para a Cidadania Plural. Os resultados revelam que as abordagens de diversas matérias, exibem diferenças simultaneamente notáveis e complementares. Nas conclusões, propomos a introdução de novos elementos com o intuito de desenvolver um método baseado numa sintaxe da transparência e na ordem de elementos fundamentais.

Palavras-chave: transparência; método de avaliação; comunicação pública; administrações locais.

Introduction[1]

The transparency of public administrations is a subject of great international interest. Its study, especially on the evaluation of its application, is being addressed in the academic world from different disciplines. In parallel, public institutions themselves apply other procedures to determine the degree of compliance of current legal regulations at the various administrative levels. In addition, civil organizations, both national and international, have adopted other systems to monitor the flow of information and to thus control the actions of governments, to promote the participation of citizens in public policies, or monitor the honesty of the governing politicians.

This plurality of interests and measurement procedures generates confusion among the evaluated subjects, who on occasion need to take into account the requirements of multiple observers who use different systems of evaluation and measurement. It also reveals both the interest in the subject and the lack of standardized criteria that guide the public by offering them rigorous, comparable results. Although it is true that legislation and administrations in each country or region exhibit their own particularities, it is equally true that other fields have solutions to this problem, such as PISA reports (Program for International Student Assessment)[2] that are promoted by the OECD. While the procedure could be improved, it is also a guarantee of impartiality, since it is based on a supranational structure that is accepted as an arbitrator and respected by the parties involved.

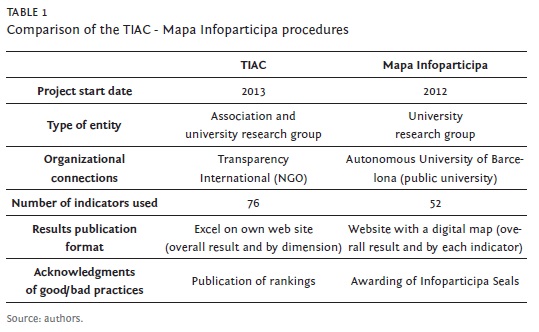

In order to validate similar procedures in the area of transparency, it is necessary to know the various methods being applied and their reasons for being used and characteristics, as well as the particularities of the evaluated administrations and the legislation regulating the right to access information. Therefore, we believe that a comparative study of the procedures being used by the Civic Association of Transparency and Integrity (Transparência e Integridade, Associação Cívica; TIAC)[3], which is the Portuguese arm of the international organization Transparency International, and the Mapa Infoparticipa[4] Project in Spain, which is part of the Laboratory of Journalism and Communication for Plural Citizenry (Laboratorio de Periodismo y Comunicación para la Ciudadanía Plural; LPCCP) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona to be important. These studies share not only common characteristics but also have important differences that when studied in depth will allow conclusions to be drawn regarding the possibility of combining both procedures and using them as a starting point for an evaluation proposal for transparency at the international level.

The relevance of a comparative evaluation is based on the fact that, in addition to sharing an object of analysis, namely local public administrations, both are consolidated procedures in their national context and have a clear intervention purpose. The evaluation of the compliance of the right to information takes on meaning when it is intended to influence reality in order to bring about a transformation without losing sight of the fact that this study is interested in developing the theory in this regard and providing academically valid results.

However, the perspectives from which the problem is being addressed differ, since the Mapa Infoparticipa project has its origins in communication sciences, whereas the TIAC project is mainly based on political sciences and law. This study will enable the determination of both the differences and the possibilities for complementarity of these two approaches that determine the design of the respective evaluation methods.

We do not intend in this study to compare the results of the application of these methods, since this is not a study of the transparency of local administrations in either country but a study of the method designed in each case. However, it should be pointed out that the number of municipalities in Spain is much greater than in Portugal[5]. Therefore, the Mapa Infoparticipa project has been carried out in several phases at different speeds in each Spanish region. We focus this comparative analysis on the work carried out in Catalonia, since the project was started in this region and Catalonia is therefore where it has been applied the longest and where it is more consolidated.[6]

Objectives and methods

The aim of this study is to determine the similarities and differences between the procedures of Transparency and Integrity (TIAC) in Portugal and LPCCP in Spain for the evaluation and promotion of transparency in local public administrations. The objective is pertinent, as it enables us to establish the differences and their causes. In this way, the complementary elements can be defined and the proposals for the design of a method applicable in different contexts can be established. In order to achieve this, a comparative analysis of the literature is carried out in which both the reports of the results and academic articles published by both groups will be used in addition to the information published on the projects’ websites.[7]

First, we carry out an analysis of the sources used for the design of the procedures. We then situate each project in its background and aims and explain the method, paying special attention to the evaluation indicators and the methods for presenting results that incentivize good practices. Last, we present the conclusions based on the most notable elements that arise from the comparison, taking into account factors that allow the two procedures to be combined, and we provide discussion points to give continuity to this work. This last section is especially important, as the comparison yields substantial points for discussion that enable us to formulate a series of proposals to address in the future.

Comparative analysis of sources

Some studies on government transparency compare practices and results from different countries. Huijboom and van den Broek (2011) presented a report of research for the Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations in which they assessed the open data strategies in five countries: Australia, Denmark, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The inquiry made a comparison of the programs, instruments, barriers, and drivers of open data policy implementation in these countries, concluding that important differences existed in how government data are published.

Jarmuzek, Orlowski, and Radziwill (2004) evaluated monetary policy transparency in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland: the three new European Union Member States that have adopted a direct inflation targeting strategy. They used two measures of transparency, institutional and behavioral, using the European Central Bank’s transparency as a benchmark for evaluating their results. They found a high degree of alignment of monetary policy transparency between the three countries and the European Central Bank. These same countries were studied by Dragos (2006) in order to pinpoint the differences in their application of freedom of information laws, in aspects such: different models in regulating freedom of information regimes, obstacles in the implementation of the law, public bodies that should apply the law, and timeframes. The findings show some resistance of political parties and of old mentalities to the further deepening of transparency.

Sirafi (2006) made a qualitative comparative case study between Sweden and Slovenia to demonstrate that the report of Transparency International on lobbying in Europe can be questioned and that a comparative study in this issue is very problematic, because the concept of lobbying is different in each country. He found that there is no clear definition of lobbying in Sweden, while in Slovenia it is regulated and clearly defined.

All of these studies compare the transparency of national governments, but other researchers are interested in studying the differences in the transparency of local governments. Pina, Torres, and Royo (2007) undertook an empirical study of 318 government websites in 15 countries of the European Union at a sub-national level, to determine the effect of e-government on transparency. They used a 73-item evaluation questionnaire divided into four dimensions: transparency, interactivity, usability, and website maturity. To evaluate the transparency, they adapted the Website Attribute Evaluation System (WAES), a methodology developed by the Cyberspace Policy Research Group. Their conclusion was that the websites have to strengthen interactivity to increase transparency, accountability, and openness. The above-mentioned authors applied the same methodology, but in this case, in 75 local government websites to analyze the evolution of e-government to assess the contribution of the different contextual factors in its development. They concluded that a real openness and a dialog with citizens was found on only a few websites (Pina et al., 2009). In another study (Pina et al., 2010), they focused on how local government websites disseminate financial information. Their conclusions were, once again, that e-government is not enough to improve transparency practices, in this case Internet financial reporting (IFR) practices.

Similarly, Navarro-Galera et al. (2014) studied the transparency about sustainability of 33 local governments on the websites of seven European countries, to compare Anglo-Saxon and Nordic areas. They used a questionnaire of 75 items based on the Global Reporting Initiative, about the publication of information on public-sector sustainability, incorporating economic, social and environmental vectors. They calculated the cumulative percentage of information disclosed in both groups of countries and concluded that Anglo-Saxon local governments make greater use of the internet to inform about sustainability. The same authors enlarged the study and made another comparative analysis of sustainability information, this time on the websites of 72 local governments in 10 European countries (Anglo-Saxon, Southern European, and Nordic). They concluded that the most transparent local governments are the Anglo-Saxon, followed by the Southern European and the Nordic. In addition, they confirmed the influence of administrative traditions on transparency (Navarro Galera et al., 2017).

Likewise, Brusca and Montesinos (2016) compare 17 countries’ implementation of performance reporting by local governments. They included Anglo-Saxon, Nordic, and Central, Western, and Southern European countries. The performance reporting systems of the countries were compared by analyzing the institutional webpages with information on performance reporting frameworks, the regulations and standards of the countries in this field, and performance reporting literature in the different countries. Findings show that there is no convergence in practice or results. Besides institutional factors influence the implementation of performance reporting.

A larger sample was studied by Gallego-Álvarez, Rodríguez-Domínguez, and García-Sánchez (2010): the 81 largest municipalities from 81 countries selected for the elaboration of the report “Digital Governance Municipalities Worldwide”, which also included the Digital Governance Index 2005, used in this comparison. This index consists of five elements: Security and Privacy, Usability, Content, Services, and Citizen Participation. They found a correlation between the municipalities that have a significant level of technological development and a higher level of improvement in e-government. Nonetheless, they did not obtain evidence of a close relationship between economic wealth and the development of digital government. According to the authors, the content of websites shows common trends among the largest cities worldwide.

All of these investigations coincide in that the political, economic, and social context of each country influences the practices of transparency, locally and nationally, and even the way of understanding this concept. That is why our research has not focused on comparing the results of TIAC and LPCCP evaluations, or on evaluating Spain and Portugal with a single instrument, but rather on comparing both methodologies to find points of convergence and divergence and to determine their causes. Consequently, the comparison should begin with an analysis of the theoretical perspectives from which each project addresses the evaluation. For this, in this section we used two sources: an article from the TIAC group, authored by da Cruz et al. (2016), and another authored by Moreno, Molina, and Simelio (2017), who form part of the LPCCP.

First, the journals in which these two articles were published define the field of study. While the TIAC article appears in an administration journal, the LPCCP article was published in the field of communication. The profiles of the teams are also apparent from the sources used. Thus, in the TIAC study, most notable are the studies published in journals that specialize in the study of public administrations or, to a lesser degree, in political sciences. Some of these are often cited, such as Public Administration Review and Government Information Quarterly. The latter, due to its more specific orientation toward information and government, is also used in the study by the LPCCP group, which bases most of its discussion on studies carried out in Spain.

In its introduction the TIAC article addresses the fundamental preoccupations to be resolved and introduces authors that are cited in the discussion later in the article, such as Piotrowsky (Cuillier and Piotrowski, 2009; Piotrowski 2010) and Jaeger, Bertot, and Grimes (Jaeger and Bertot, 2010; Bertot, Jaeger, and Grimes, 2010), the latter being used to introduce, among other issues, the problem of the ambiguous use of the concept of transparency.

The LPCCP article also cites some of these authors (Bertot, Jaeger, and Grimes, 2010), but its argument takes only one direction: the importance of the right to information and to public participation as well as the need for municipalities to use information to show themselves to be effective and trustworthy. For this, they refer to Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch, (2012), who are also mentioned in the discussion of the TIAC article, and also introduce Spanish literature, such as Campillo Alhama (2012). This line of reasoning continues with a defense of the importance of the evaluations to guarantee accountability based on articles by Cameron (2004) and Giménez (2012), and the right of citizens to obtain this information (Rivero, Mora, and Flores, 2007).

In conclusion, the LPCCP article is based on communication studies and gathers authors, studies, and discussions that lead in this direction. Thus, Spanish authors are used to emphasizing the importance of the use of ICT to facilitate the understanding and reuse of information (Garriga, 2011; Calvo, 2013; Rivero, Mora, and Flores, 2007; Pina, Torres, and Royo, 2010) and addresses the importance of the reduction of the costs of the publication and distribution (Roberts, 2006), the relationship with the citizens (Borge, 2007), and the reduction of corruption (Anderson, 2009). For this, importance is given to the increase in interactivity as a driver of new forms of governance, of the legitimization of government action, and of the opening of spaces for accountability and citizen empowerment (Pina, Torres, and Royo, 2007; Gandía, Marrahí, and Huguet, 2016; Cameron, 2004; Bertot, Jaeger, and Grimes, 2012). Finally, the LPCCP article notes that ICT require changes in management models in order to increase transparency and participation (Bonsón et al., 2012), contributing studies in Spain that relate these issues and that highlight the difficulties for administrations in adequately using communication resources (Beltrán and Martínez, 2016; Gértrudix, Gertrudis, and Álvarez, 2016; del Rey, 2007; Rivero, Mora, and Flores, 2007; Pina, Torres, and Royo, 2007; Moreno and others, 2013).

This perspective, which is based on communication studies and which therefore gives great importance to technological mediation, is also addressed in the TIAC study from the very first paragraph, which highlights the crucial role of the Internet in promoting government transparency (Cullier and Piotrowski, 2009; Jaeger and Bertot, 2010; Transparency International, 2015). The authors also point out that technology is a vehicle for generating and increasing trust in the government (Kim and Lee, 2012; Welch, Hinnant, and Moon, 2005, Tolbert and Mossberger, 2006; Pina, Torres, and Royo, 2007; Moon, 2002; Welch, Hinnant, and Moon, 2005; Cullier and Piotrowski, 2009) and relate the availability of information with empowering citizens to participate (da Cruz and Marques, 2014). However, they discuss the centrality of the issue and the excessive importance given to websites, which are unidirectional, decontextualized, and excessively structured communication spaces (Meijer 2009; Dawes 2010).

On the other hand, it is striking that a study promoted by an arm of Transparency International (TI) does not address the relationship between transparency and the prevention of corruption until much later in the article. Moreover, when it does appear, both arguments in favor of its legitimatizing use and discussions on its effectiveness are presented in line with the studies carried out by Lindstedt and Naurin (2010), who state that transparency is effective in preventing corruption only when other conditions are also met. In addition, the problems of corruption and mismanagement are mentioned to explain the distancing between citizens and political affairs (King, Feltey, and Susel, 1998; Innes and Booher, 2004; Stivers 2008; Piotrowski and Bertelli, 2010) and, in agreement with Stivers (2008), so that citizens can enjoy greater participation in decisions and co-production of services and in accountability, and, in short, to promote empowerment (Hood and Heald 2006; Bauhr and Grimes 2014; Piotrowski and Van Ryzin 2007; Piotrowski and Bertelli 2010).

It is very interesting to observe how the TIAC article also discusses other effects of transparency, not always positive, on governments and on improving citizens’ perception of them. Thus, they cite studies that warn of the danger of undermining trust when decision-making procedures are made transparent or when doubts arise regarding the mechanistic relationship between transparency and trust in public policies when transparency is understood and executed by overwhelming the user with excess technical information (de Fine Licht, 2011 and 2014). However, they conclude that from the point of view of the rights of citizens there needs to be a regulatory framework on transparency that results in knowledge upon which to promote public participation.

A further interesting discussion alludes to the effects that transparency can have depending on the context in which information is produced and received, noting the studies of Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, and Im (2013), who state that in countries in which there is no tradition of transparency or open government, citizens perceive these new practices favorably.

With regard to the methodology, the authors of the TIAC article point out that the studies performed have two limitations: the equal value of all the indicators, which according to da Cruz and Marques (2013) yields incorrect results, which TIAC aims to resolve in their project through a process of participation in the design of their method and the delegation of the evaluation in the answers of the subjects evaluated, which will be resolved by the direct evaluation of the websites.

The second limitation has to do with the project’s method itself. It is compared with those of TI in other countries, although differing with the inclusion of stakeholders in the design decisions, in line with Figueira, Greco, and Ehrgott (2005), the multi-criteria structure (Munda, 2004), and with support regarding the scoring procedure in da Cruz and Marques (2014). Finally, the use of rankings based on Cooper (2004) and Piotrowski (2010) is argued in order to send signals to policy-makers, although it is recognized that the method used is a quantitative reduction of a complex problem without including an analysis of the quality of the information (Bannister 2007; Dawes 2010).

Background, objectives, procedure, and publication of results

Municipal transparency index, TIAC

Civic Association of Transparency and Integrity (TIAC) was founded as an association in 2010. It is the Portuguese arm of Transparency International[8], an organization that in its motto “the global coalition against corruption” focuses on transparency as a means of preventing corruption.

However, TIAC goes further:

Our aim is to achieve a fairer society and democracy of quality in Portugal, advocating for effective access to information and the creation of an informed, strong and participatory citizenry.[9]

It therefore includes other objectives related to the improvement of democracy, for which it carries out campaigns, research, educational actions, and collaboration with different types of public institutions or private organizations. TIAC also boasts of a support service for complainants in addition to the monitoring of the state of transparency.

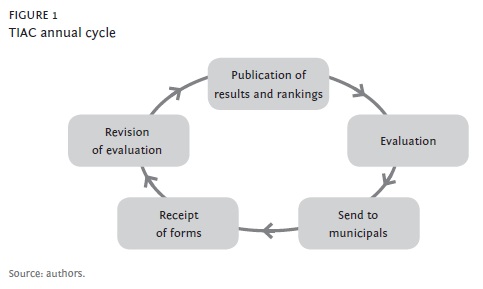

The study method (see Figure 1) starts with the evaluation of websites, which is carried out by the TIAC group. The results are sent to the municipalities in order that they can compare them and, if discrepancies are found, the municipalities can report these discrepancies. The work group revises the modification proposals received from the municipalities and revises the evaluations when a discrepancy has been demonstrated. Finally, the results of the annual wave are published.

Since 2013 TIAC has published an annual Municipal Transparency Index (MTI), which was designed, constructed, and implemented in large part by a group of scholars from Portuguese universities. This Index is the result of analyzing the transparency of the 308 Portuguese municipalities’ webpages. The results are published in Excel format in a specific section of its main website. Following the list of municipalities in alphabetical order and presenting the overall results and the results for each dimension, in 2013 two tables were included, one with the ranking of the 10 best results and the other with the 10 poorest. In 2014 and 2015 these tables were replaced by two others showing the complete ranking, the first ordered from first to last and the second, from last to first. In 2016, in addition to these same tables, two additional ones were included that showed the improved positions in the ranking in one and the positions lost in the other.

Mapa infoparticipa, LPCCP

The Mapa Infoparticipa was also defined on the basis of the existing academic literature and on the previous studies of the LPCCP itself. These studies demonstrated that the media was excluding plural citizenry from the public debate as a political subject and that it was therefore necessary to humanize information, that is, to innovate journalism in order to facilitate participation of the plural citizenry.

Consequently, the need arose to develop instruments that made visible the existence of the lack of information and the deficiency of quality in publications, and that helped to resolve these problems. The main aim is to improve communication activity in order that democratic quality consequently advances:

[…] to develop methods and tools to innovate journalism and create information that facilitate[s] the plural citizenry - women and men of any age, status, origin, ability, need - to exercise their rights in a fully democratic society.[10]

Therefore, a website and the complete procedure was designed, taking into consideration three aims: 1) to ensure that any citizen could access and understand information, 2) to establish mechanisms in order that the group could work online cooperatively, and 3) publish the results with the aim of encouraging improvements. Thus, the results are published in map form in order that everyone can make a personal reading of it that is not subject to a pre-established order, taking into account their main interests first and comparing the information published with what they know from the experience of the social positions they occupy. Thus, contents are provided to build a new pluralistic, humanistic, and political knowledge that is ranked and online.

On the other hand, the indicators are in the form of questions that the evaluators have to answer in the same way that any other individual would do (whether or not the information can be found), carrying out what is defined as a civic audit of transparency of local administrations (Molina, Simelio, and Corcoy, 2017) and avoiding any technical language that might hinder understanding.

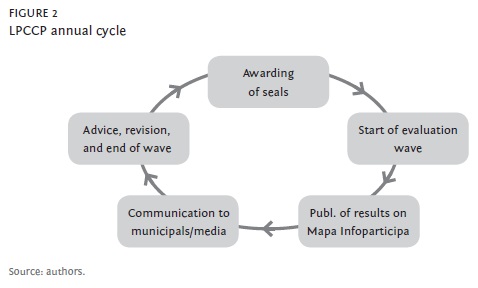

The annual wave begins with the evaluation of the websites of the municipal institutions by the research team and the publication of the results on the Mapa Infoparticipa website progressively, that is, the full evaluation is not published on a specific date, but rather the results are published as the evaluations are carried out in order that the policy-makers of the municipalities or any other person can see the results immediately after the evaluation, both globally and indicator by indicator.

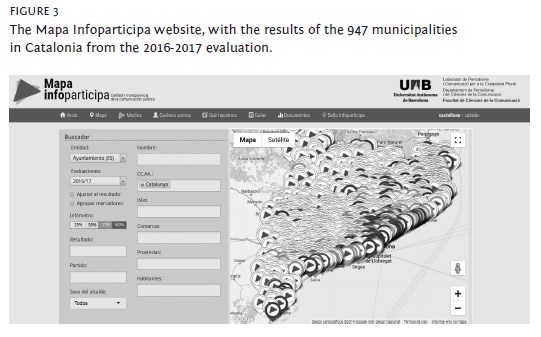

These results are published on the Mapa Infoparticipa website in a geolocalized way by means of a sign over the municipal with a color automatically assigned by the system that identifies: the municipalities that achieve fewer than 25% of the positive indicators (white); those that obtain between 25 and 50% (yellow); those that exceed 50% and up to 75% (light green); and those that obtain more than 75% (dark green). Finally, the municipalities that obtain an Infoparticipa award are marked with a red bow on a dark green background.

The next step is the preparation of reports, which are sent to the media, and the communication of the publication of results to the municipalities. Therefore, a communication strategy in the form of the map, the media, and direct communication is used to reach all interested parties.

The municipalities communicate any discrepancies or improvements they can carry out by sending emails to the project’s researchers, who also advise on the application of the indicators following a guide prepared for this purpose, pursuing the objective of the project, namely to achieve improvements in the transparency of local administrations. The evaluators verify that the information received is correct and update the evaluation on the Mapa Infoparticipa website when appropriate.

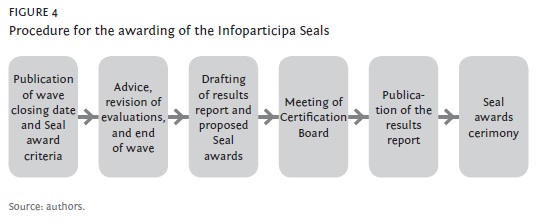

A closing date for the wave is established beforehand in order that all of the municipalities are aware of it. In this way a result of all the municipalities is obtained simultaneously, which allows a wave report of the results to be prepared, which subsequently enables us to decide which municipalities will be recognized by means of an Infoparticipa Seal for having obtained the best scores. The requirements for obtaining a Seal are also published on the Mapa Infoparticipa website in order that municipalities aspiring to obtain one know in advance the evaluation percentages they must obtain.

This report contains a grant award proposal, which is sent to the Seal Certification Board, which has the capacity to validate it or reject it either totally or partially. The Board was created by resolution of the Rector of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) in 2014 and is chaired by a person of recognized prestige in the field, who is proposed by the Rector of the UAB, and composed of those who preside over each of the following institutions: The Rectorate of the UAB, The Faculty of Communication Sciences of the UAB, The Catalan Association of Municipalities, The Catalan Federation of Municipalities, The Catalan Antifraud Office, The Catalan College of Journalists, the Association of Public Communication, The Confederation of Neighborhood Associations of Catalonia, The University of Girona, and the team promoting the project.

Once the awards have been approved, this information is published on the Mapa Infoparticipa website and all mayors obtaining an award are invited to an awards ceremony chaired by the Rector of the UAB and a representative of the Generalitat of Catalonia. The award consists of a Certificate and an accrediting Seal that can be published on the municipal website.

Indicators

The definition of the TIAC indicators was based on studies carried out in different countries and a proposal of 176 indicators was finally submitted for the consideration of a group of experts, who determined the final relationship of the index in 76 indicators divided into 7 dimensions. This group consisted of 15 individuals, including academics, lawyers, the heads of different political areas at various levels of the administration or individuals with experience in these fields, and activists and leaders of workers’ groups.

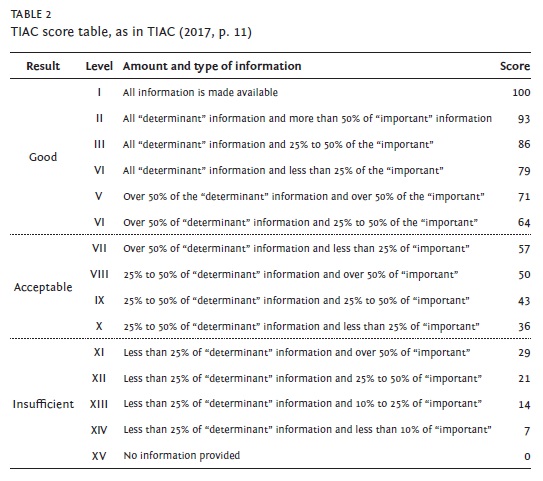

Regarding the calculation of the evaluation results, the same team of experts selected a group of 21 determining indicators. This difference is key, since the final percentage obtained weights the relationship between published “determinant” information and the rest, considered “important”. Moreover, each dimension has a different value or weight over the whole, such that, for example, dimension A, with 18 indicators, has a weight of 0.15 out of 100, while dimension G, with 10 indicators, has a weight of 0.25 out of 1. This weighting was also decided in a meeting carried out with the group of experts, described in da Cruz et al. (2016). Finally, three categories of results were established: good, from 64%; acceptable, from 36%; and insufficient. These three categories are in turn divided into a total of 15 levels in which the relationship between the determinant indicators is considered, as can be seen in Figure 5.

The first list of Mapa Infoparticipa indicators was formulated based on the Municipal and Local Regime Law of Catalonia[11] and on documents written by the project group itself, such as the Decalogue of Good Practices in Local Public Communication[12], until the Spanish Law of Transparency was approved[13] and later, the Catalan Law of Transparency.[14] This new legal framework, which is mandatory for public administrations, led to a redefinition of the evaluation indicators that were agreed upon with other agents. The first meetings were attended by representatives of the Regional Ministry of the Government of Catalonia, the body responsible for local administrations and, in parallel, meetings were held with representatives of the two municipal entities of Catalonia, with three of the four Provincial Councils of Catalonia and with representatives of interested municipalities of different characteristics due to the political color of the government or population size. The final list of 52 indicators, divided into 5 groups, was closed by the LPCCP and the Regional Ministry of the Generalitat of Catalonia. Since then, every year some changes have been incorporated in the indicators or the evaluation guide. These modifications are usually carried out at the initiative of the LPCCP group and are submitted for the consideration and approval of the Infoparticipa Seal Certification Board.

The scoring system is very simple. Starting from the consideration that all the indicators have the same value, the final score is the percentage of compliance over the total. However, differences are made between municipalities, depending on the number of inhabitants, to obtain Seals[15].

The 7 dimensions of the TIAC procedure are:

a) Information about the organization, social composition and functioning of the municipality.

b) Plans and reports.

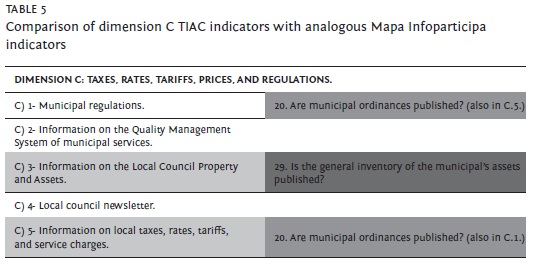

c) Taxes, rates, tariffs, prices, and regulations.

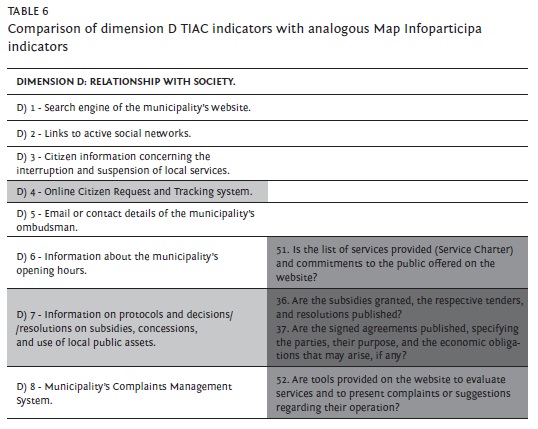

d) Relationship with society.

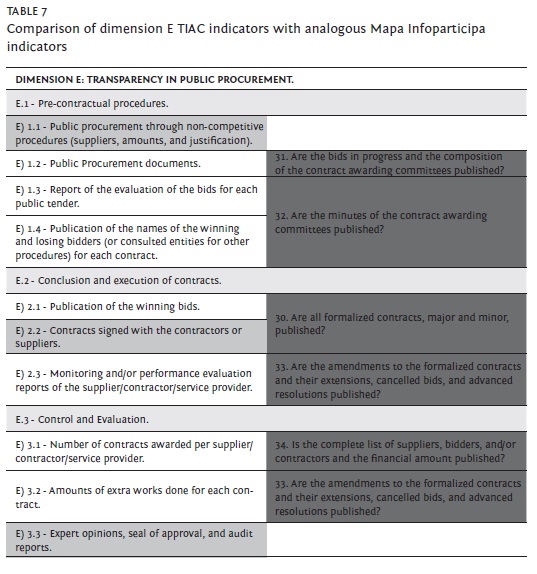

e) Public procurement.

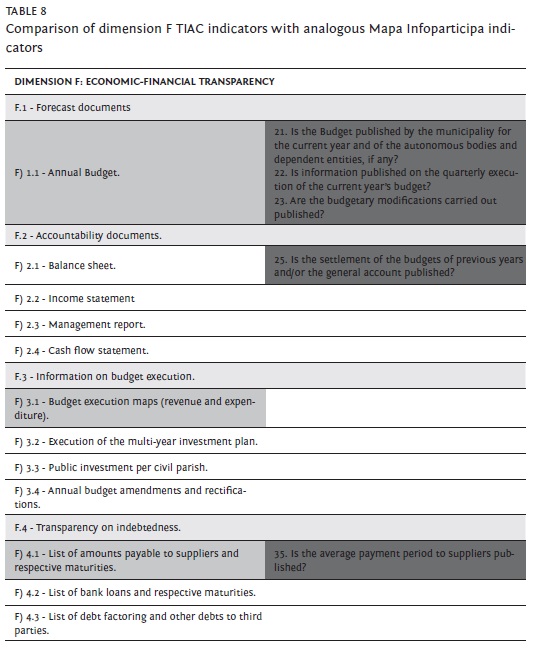

f) Economic-financial transparency.

g) Transparency in urban planning.

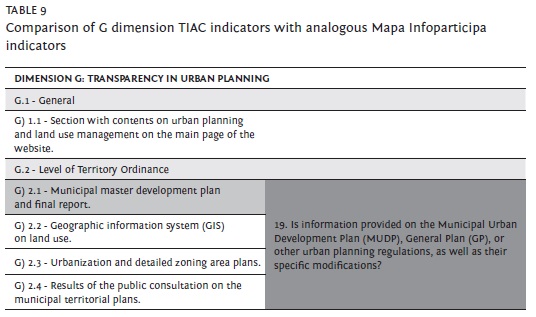

Some have subdivisions, which can be seen in Table 2.

The Infoparticipa procedure divides the 52 indicators into two groups and 5 subgroups:

1. Corporate transparency

1.1 Who are the political representatives?

1.2 How do they manage collective resources?

1.3 How do they manage economic resources: budgets, salaries, recruitment, subsidies, etc.?

2. Information for participation

2.1 What information do they provide regarding the municipality and the management of collective resources?

2.2 What tools do they offer for citizen participation?

To make the comparison between the indicators, in the following tables we have placed the TIAC indicators in the first column in the same order in which they are published (highlighting in yellow those considered determinant) and numbered, with those of the Mapa Infoparticipa procedure in the right column next to the TIAC indicator with which it presents greater parallelism, indicating with colors the group to which they belong: 1.1 yellow; 1.2 green; 1.3 blue; 2.1 lilac; 2.2 brown.

The first large group in Portugal is (A) Information on the organization, social composition, and functioning of the municipality, while in Spain the heading (1) Corporate Transparency is used, which, although more eclectic, suggests a very approximate content.

Within these, the first subsection in Portugal reads (A1) Information on elected officials of the municipality, which is very similar to the Spanish equivalent (1.1) Who are the political representatives? However, already the first indicator is different in each case. While the TIAC project seeks information on the assignment of positions in the chamber, its equivalent in the LPCCP project is found in indicator 14, already in the second group of indicators on management, which demands the publication of the corporation’s organizational chart, including the functions of each person. In contrast, in Spain indicators 1, 3, and 5 request basic profile data: full name of these representatives, photograph and political party to which they belong, first about the mayor and then about the members of the government, and finally about the members of the opposition.

Next, indicator A1.2[16] requests a biographical note about the members of the chamber, information which is perfectly comparable to that requested in indicators 2, 4, and 6 in Spain and, as in the previous case, by areas of responsibility (mayor, members of the government, members of the opposition). These first 6 LPCCP indicators have a clear impact on the final score, which is the result of the publication of elementary information, but also show how significant the treatment of the opposition is in this procedure, as will be seen in other sections, and the importance given to the publication of information as relevant as belonging to a political party, information that in Portugal is not specifically indicated.

(clique para ampliar ! click to enlarge)

The following indicator, A1.3, regarding the publication of emails of the members of the chamber, has an equivalent in 10 and 11, but in this case it involves a request for information on social networks, websites, telephone numbers, and other forms of communication with these representatives. Here the communication and participation perspective seems to be clearly acting, that is to say, dialog with the political representatives. It should also be noted that in Portugal indicator A.3.6 requests the emails of the various bodies, namely the council, assembly, and parishes. In this regard, the difference in administration between both countries determines this need, which in Spain is solved more easily since there is only one institution.

In contrast, indicators A1.4 and A1.5, regarding the assets and interests of the representatives, is a single indicator (8) in Spain.

In the section on remuneration, A1.6 requests representation expenses, while in Spain (7) the complete salary is requested. Regarding the salaries of the so-called positions of trust, there is unanimity in both procedures (A1.7 and 27), although in Spain this indicator is in the third group of questions on the management of economic resources, as well as another indicator that does not appear in Portugal regarding staff salaries (26), which in addition to being an important entry in all municipalities, allows other work or social issues to be visualized.

In the second subgroup of indicators in Portugal (A.2, Information regarding municipal staff), the first two indicators, on the annual social balance of the municipality and the professional compatibilities (which is considered a priority), have no equivalent in Spain (A2.1 and A2.2).

In Spain, indicators A2.3 and A2.5 are covered by indicator 28, since both job vacancies and the development and result of the tenders are requested. However, indicator A2.4 has no equivalent, since contracts for the provision of services have a different procedure that is not included in that indicator.

The powers of the governing bodies are included in indicator A3.1, which corresponds to indicators 12 and 13. The latter includes the requirement to publish the work schedule, which in Portugal is included in indicator A3.3 and which in Spain is expanded on in indicator 15 by demanding independently the announcements of the municipal plenary meetings. Indicators A3.4 and A3.5, concerning the decisions of the governing bodies, are covered by two indicators in Spain (16 and 17), although with different drafts.

Indicator A.3.2, on ethical codes, has no equivalent in Spain, nor A.3.6, which requests email addresses of the governing bodies. However, in Spain the latter does not have the same meaning because of the different structure of the governing bodies.

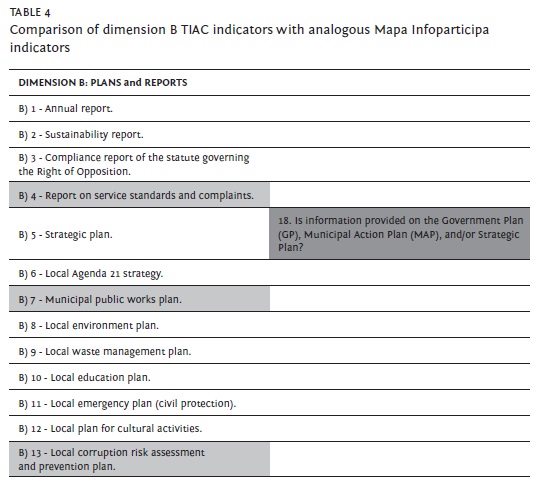

Regarding dimension B, which in Portugal covers plans and reports, it is clear that of the 13 indicators, only B.5 has an equivalent in Spain in indicator 18 regarding the publication of the municipal strategic plan. Therefore, there are 12 indicators without an equivalent. These evaluate the existence of projects on municipal activities, sustainability, claims and suggestions made, local Agenda 21, public works, the environment, solid waste, education, civil protection, culture, and corruption prevention. The presence in four of these indicators on issues related to the environment (B.2, B.6, B.8, and B.9) is striking. On the other hand, in Spain it is deemed that the Action Plan or the Strategic Plan must contain all of these plans or those that the municipal government intends to carry out. The main issue is that the Portuguese procedure reveals more clearly the shortcomings. This is a notable difference in that more detail is requested in Portugal.

In section C of the TIAC project, which is composed of 5 indicators, only 3 have any correspondence in Spain. Indicators C.1 and C.5 can be compared with indicator 20, which requests the publication of municipal ordinances. Moreover, C.3 and 29 are clearly equivalent, since in both cases the publication of the municipal inventory is requested. There is no parallel in C.2, concerning quality management, or in C.4, which evaluates the publication of the municipal bulletin, a resource that not all municipalities have in Catalonia (they are published in the provincial bulletin), which is why it is not generally possible to request this information.

In dimension D, only 3 of the 8 TIAC indicators have an equivalent, namely D.7, which has its equivalents in indicators 36 and 37, regarding subsidies granted and signed agreements, D.8, which in Spain is indicator 52 and in both cases requests that there be a space on the website for citizens to submit complaints or suggestions, and D.6, although it is necessary to point out that indicator 51 includes a request for the complete list of services.

On the other hand, in Spain there is no request for a search engine on the website (D.1), nor, surprisingly, links to social networks (D.2), or information concerning the operation of the transport system (D.3.), the tracking of online administrative systems (D.4), or the ombudsman (D.5), as this entity does not exist in all municipalities.

Dimension E, on transparency in public procurement, is composed of 10 indicators that correspond to 5 indicators in Spain. Only E1.1 (partly covered by indicator 37), concerning direct awards, and E3.3, which covers audit reports on these procurements, have no equivalence.

Section F, on economic and financial transparency, is composed of 12 indicators. The first (F1.1) corresponds to 3 indicators in Spain, where in this case more detailed information is requested, since in addition to the annual budget, indicator 22 requests quarterly information on its execution while 23 requests publication of any modifications carried out. The settlement is requested in a very similar way (F2.1 and 25), but there are other indicators that are not requested in Spain (F2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4).

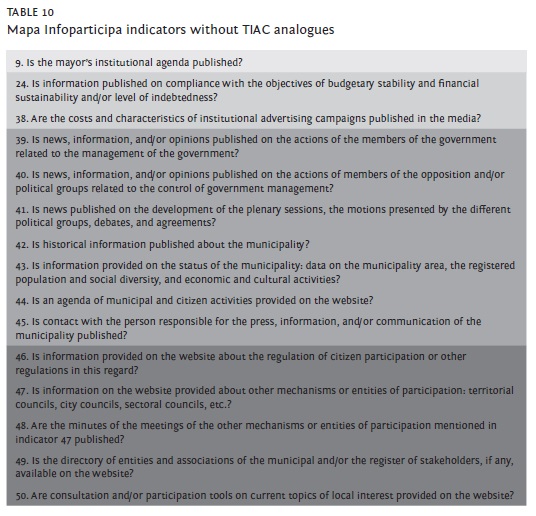

In section G, which covers transparency in urban planning and which is composed of 10 indicators, the first 5 (G2.1 to G2.5) are equivalent to 1 in Spain concerning the publication of planning standards (19), while in Spain the presence of this information is not required on the main page of the municipal website (G1.1) nor in the 4 indicators in section G.3 regarding urban management.

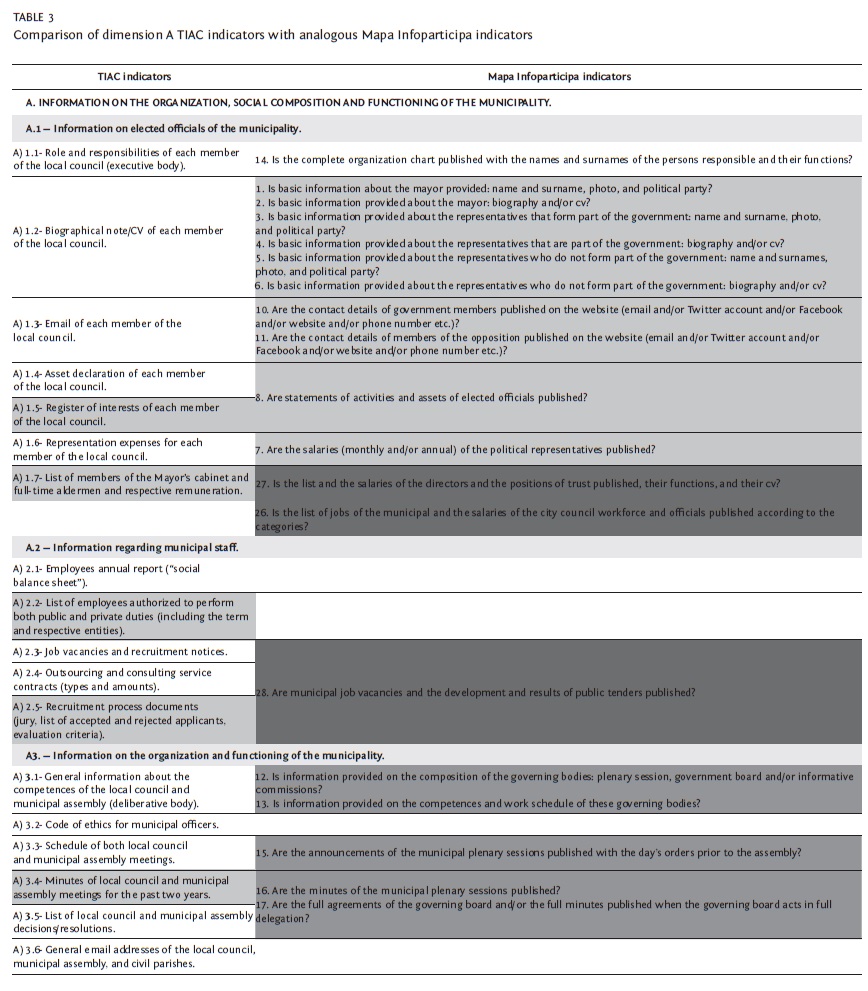

Finally, none of the Spanish indicators concerning information has an equivalent in Portugal (39 to 45), nor 5 of those in the participation section (46 to 50), nor 9 indicators, on the mayor’s institutional agenda, 38, concerning the cost and characteristics of institutional advertising in the media, or 24, regarding the compliance of stability objectives.

Conclusions and discussion

It is clear that the approach from the perspective of communication in one case and political sciences in another determines the characteristics of the overall procedure, although the magnitude of these differences in the definition of the indicators that ultimately lead to the evaluation result and therefore enable us to determine which administrations are sufficiently transparent and those that are not is surprising. Not even in the indicators that are considered to be determinant in the TIAC procedure is there agreement, and a number of the sections in one procedure are ignored or practically non-existent in the other and vice versa. In the definition of indicators, it is perceived that in the case of TIAC, despite the broad formulation of the problem, the concept of transparency as a preventive element of TI’s own corruption dominates, which results in a detailed list of data required. However, the LPCCP project is comparatively less specific in terms of management and planning issues (although the sections on procurement and economic-financial transparency include a good number of indicators) but highlights politically relevant aspects such as the presence or not of the opposition in information publishing systems as part of the institution as a representative of citizens. However, the presence of certain indicators is clearly determined by the characteristics of the administrations in each country or by other legal regulations that entail publication obligations.

Despite this, we consider that the indicators of both proposals are perfectly compatible and complementary. The sum of the indicators from both perspectives allows the various aspects of active transparency to be considered, adding precision to the information demanded with information quality principles that bring transparency closer to its objective, which is to ensure that citizens can use this information to follow government action and participate and to ensure that governments are accountable for their mandate.

Likewise, the procedures present strong similarities in their annual cycle and a common interest in considering transparency as a fundamental element for the development and proper functioning of democracy. The manner of publication differs in that the TIAC classifies the municipalities from 1 to 308, while the LPCCP gives them a final score from 0 to 100% and classifies them by quartiles indicated by colors on a map: white for the municipalities that obtained from 0 to 24.99%, yellow from 25 to 49.99%, light green from 50 to 74.99%, and dark green from 75 to 100%, so that citizens can easily visualize the group to which each municipality belongs.

The evaluation of the LPCCP also includes an award for the municipalities with the best results. There are two different approaches: the TIAC is based on publishing to identify and then improve those municipalities’ with subpar practices, and the LPCCP in addition to the same strategy, also rewards excellent performance, to encourage good practices in local governments. In spite of the differences, both approaches have the common goal that the municipalities improve their communication toward citizens, beyond a simple assessment. It could be that the double strategy of the LPCCP manages to strengthen the effort in the achievement of that goal, since it uses both negative and positive reinforcement. However, we must not forget that there is a risk in the rewarding of transparency best practices, as municipalities can publish innacurate information simply in order to obtain the award. This strategy therefore requires an effort of continuity in the evaluation, that is, to follow up on the awarded municipalities so that the improvement obtained thanks to the stimulus of the prize will be maintained over time.

On the other hand, the LPCCP bases its work fundamentally on the results of previous studies, while TIAC relies more extensively on external theoretical studies conducted in different contexts. This latter option allows wider problems associated with the issue to be addressed, which is a very important aspect if the intention is to internationalize a procedure. However, the LPCCP project attaches more importance to the subsequent phase of making the results visible and promoting improvements. In this regard, both the map publication tool and the awarding of accreditations are useful strategies.

With regard to the scoring system, we do not consider the greater effectiveness of one system over the other in achieving the proposed objectives, in evaluating the transparency of the websites, or in achieving an increase in their transparency to be sufficiently proven. This point requires further in-depth analysis that goes beyond the framework of this article, but we provide some elements. It can be understood that some information is more important than other information but the list can differ depending on who considers it: experts, citizens with business interests, neighborhood organizations, or others. Thus, unanimity in the technical decision of the evaluations will not have equivalence in the reading phase of results. On the other hand, the dominant idea regarding the function of transparency will significantly change the evaluation in favor of some or other indicators, as can be seen from the comparative analysis. It should also be noted that it may be equally reasonable to understand that having information is an elementary step and that the weighting must act on the quality elements of publication in order to thereby favor access and understanding. Finally, a simple calculation is understandable and replicable by any person, while a more complicated calculation can create a distancing effect from the evaluation carried out and the procedure, which is an undesirable consequence when social repercussion is sought, for which simplicity and clarity are necessary. Despite this, the expert weighting of the MCDA technique has a very important benefit: it allows adjusting the indicators’ importance to different contexts, asking stakeholders in each country, and even other concern groups to complement their approach. This can be the first step in exporting a model to assess transparency in different countries, which is adaptable to each context, because there are many common transparency indicators, but they do not have the same importance everywhere.

In view of these conclusions, it is necessary to continue discussing certain issues, especially if advances in the definition of an international procedure are to be achieved, be it in Europe, in Ibero-America, or both, which allows the transparency of administrations in different countries to be compared in order to generate a recognizable standard to diagnose whether the rights of citizens to information in different locations and states are guaranteed.

To begin with, it should be noted that there is no shared paradigm. As we have seen, depending on the perspective of the studies, certain priorities are emphasized, sometimes insisting on the publication of data or information and sometimes on the cross-cutting principles that the publications must comply with in order to be effectively transparent. It seems that the logical thing would be to combine both perspectives. However, this would require teams with sufficient funding that could train the evaluators to carry out quality work and evaluations that take a long time to be carried out given the nature of the work, its complexity, and the precision with which it must be conducted in order to avoid errors that arbitrarily subjugate the work of the administrations, thereby putting at risk their credibility and that of the political leaders who govern them under a democratic mandate.

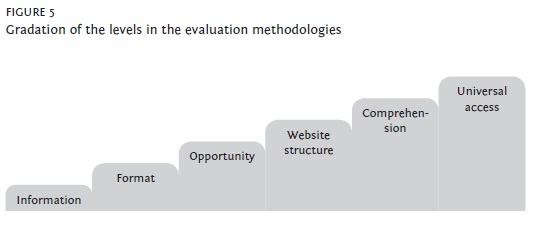

We provide a scale of the elements that must make the information provided transparent and that therefore have to incorporate the evaluation methodologies for their implementation:

• The first level relates to the confirmation of the publication of the information requested. This level corresponds to the advertising obligations stipulated by the legislation, which may be complemented with other requirements stipulated by the indicators in the evaluation procedure.

• The second is the verification that the publication formats are open and easily shareable.

• The third relates to the opportunity level. By this we mean that documents must be published at the appropriate time in order to provide up-to-date information that can be used at the time it is useful to generate knowledge and democratic dialog.

• The fourth concerns the website structure, checking that documents are easily found without the need to resort to external search engines and that they can be found within a maximum of three steps from the home page.

• The fifth covers the communicational level, which requires that the information is understandable and, therefore, also requires the use of current news spaces to disseminate information on government action and the management of the institution (Manfredi, Corcoy and Herranz de la Casa, 2017).

• The sixth is universal accessibility, that is, the possibility that any person, considering different possibilities, capacities, and levels of training, can access information, both written and audiovisual (Sánchez-Labella, Simelio and Moreno, 2017).

At the same time, it is necessary to structure the procedures in such a way that they are effective and also understandable for the agents involved and for any other interested person. In this regard, we propose the development of an evaluation structure that we could refer to as the syntax of transparency. This implies that we will serve an evaluated subject governed by persons who hold responsibilities within the framework of government and government-controlled bodies who plan and carry out actions with the participation-collaboration of other agents using specific resources that they must manage correctly. Therefore, they must account for their results, report promptly, and establish communication channels with citizens, whether individually or through organizations.

This scheme allows a logical order of sections and indicators, which supports suborders and alterations in their linearity, thereby facilitating an understanding of the method and orienting the systems of content publication.

In this context, we confirm that multidisciplinary work in this field, from political and legal sciences to communication sciences, is essential to address this issue, which is not only a legal or administrative compliance but is also complementarity between governmental and non-governmental organizations. Therefore, the procedure acquires a civic perspective, using a methodology that recognizes that citizens are able to find and make use of this information.

Finally, it is worth noting that despite the interest of international institutions in promoting transparency, it repeatedly appears in documents as only a declaratory term. Similarly, national laws establish the principles but not the application procedures that must be subsequently carried out. This study shows that from the academic field we also recognzse that the problem is not yet solved, but that we have made an advance in the diagnosis and in the proposed solutions. We must continue working to solve it by agreeing on what we are discussing and how the results will be used by citizens, which is also not well-studied, although we have pointed out some areas.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, T. B. (2009), “E-government as an anti-corruption strategy”. Information Economics and Policy, 21(3), pp. 201-210. DOI: 10.1016/j.infoecopol.2008.11.003 . [ Links ]

BANNISTER, F. (2007), “The curse of the benchmark: an assessment of the validity and value of e-government comparisons”. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 73(2), pp. 171-188. DOI: 10.1177/0020852307077959 . [ Links ]

BAUHR, M., GRIMES, M. (2014), “Indignation or resignation: the implications of transparency for societal accountability”. Governance: an International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions, 27(2), pp. 291-320. DOI: 10.1111/gove.2014.27.issue-2. [ Links ]

BELTRÁN, P., MARTÍNEZ, E. (2016), “Grado de cumplimiento de las leyes de transparencia, acceso y buen gobierno, y de reutilización de los datos de contratación de la Administración central española”. El Profesional de la Información, 25 (4), pp. 557-567. doi.: 10.3145/epi.2016.jul.05 [ Links ]

BERTOT, J. C., JAEGER, P. T., GRIMES, J. M. (2010), “Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: e-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies.” Government Information Quarterly, 27, pp. 264-271. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.03.001. [ Links ]

BERTOT, J. C., JAEGER, P. T., GRIMES, J. M. (2012), “Promoting transparency and accountability through ICTs, social media, and collaborative e-government”. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 6(1), pp. 78-91. DOI: 10.1108/17506161211214831. [ Links ]

BONSÓN, E., et al. (2012), “Local e-government 2.0: social media and corporate transparency in municipalities”. Government Information Quarterly, 29(12), pp. 123-132. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2011.10.001. [ Links ]

BORGE BRAVO, R. T. (2007), “Nuevas tecnologías y regeneración de la democracia”. In L. Cotino-Hueso, Democracia, Participación y Voto a través de las Nuevas Tecnologías, Granada, Comares, pp. 25-34. [ Links ]

BRUSCA, I., MONTESINOS, V. (2016), “Implementing performance reporting in local government: a cross-countries comparison”. Public Performance & Management Review, 39, pp. 506-534. DOI: 10.1080/15309576.2015.1137768. [ Links ]

CALVO GUTIÉRREZ, E. (2013), “Comunicación política 2.0 y buen gobierno”. In M. Römer-Pieretti, Miradas a las Pantallas en el Bolsillo, Madrid, Universidad Camilo José Cela, pp. 70-80. [ Links ]

CAMERON, W. (2004), “Public accountability: effectiveness, equity, ethics.” Australian Journal of Public Administration, 63(4), pp. 56-67. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-8500.2004.00402.x. [ Links ]

CAMPILLO ALHAMA, C. (2012), “Investigación en comunicación municipal: estudios y aportaciones académicas”. Revista de Comunicación Vivat Academia, 14(117), pp. 1035-1048. DOI: 10.15178/va.2011.117E.1035-1048. [ Links ]

COOPER, T. L. (2004), “Big questions in administrative ethics: a need for focused, collaborative effort.” Public Administration Review 64 (4), pp. 395-407. DOI: 10.1111/puar.2004.64.issue-4. [ Links ]

CUILLIER, D., PIOTROWSKI, S. J. (2009), “Internet information seeking and its relation to support for access to government records.” Government Information Quarterly, 26, pp. 441-449. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2009.03.001. [ Links ]

DEL REY MORATÓ, J. (2007), Comunicación Política, Internet y Campañas Electorales: de la Teledemocracia a la Ciberdemocr@cia, Madrid, Tecnos. [ Links ]

DA CRUZ, N. F., MARQUES, R. (2013), “New development: the challenges of designing municipal governance indicators.” Public Money & Management, 33(3), pp. 209-212. DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2013.785706. [ Links ]

DA CRUZ, N. F., MARQUES, R. (2014), “Scorecards for sustainable local governments”. Cities: The International Journal of Urban Policy and Planning 39, pp. 165-170. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2014.01.001. [ Links ]

DA CRUZ, N., et al. (2016), “Measuring local government transparency”. Public Management Review. doi. 10.1080/14719037.2015.1051572 [ Links ]

DAWES, S. S. (2010), “Stewardship and usefulness: policy principles for information-based transparency.” Government Information Quarterly, 27(4), pp. 377-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.07.001. [ Links ]

DE FINE LICHT, J. (2014), “Policy area as a potential moderator of transparency effects: an experiment.” Public Administration Review, 74(3), pp. 361-371. DOI: 10.1111/puar.2014.74.issue-3. [ Links ]

DRAGOS, D. C. (2006), “Transparency in public administration: free access to public information. A topical comparative analysis of several jurisdictions from Central and Eastern Europe”. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 17, pp. 26-42. Available at http://rtsa.ro/tras/index.php/tras/article/view/331 [ Links ]

FIGUEIRA, J., GRECO, S., EHRGOTT, M. (2005), Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys, Boston, Springer. [ Links ]

GALLEGO-ÁLVAREZ, I., RODRÍGUEZ-DOMÍNGUEZ, L., GARCÍA-SÁNCHEZ, I.-M. (2010), “Are determining factors of municipal E-government common to a worldwide municipal view? An intra-country comparison”. Government Information Quarterly, 27, pp. 423-430. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2009.12.011. [ Links ]

GANDÍA, J. L., MARRAHÍ, L., HUGUET, D. (2016), “Digital transparency and Web 2.0 in Spanish city councils”. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), pp. 28-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2015.12.004. [ Links ]

GARRIGA PORTOLÀ, M. (2011), “¿Datos abiertos? Sí, pero de forma sostenible”. El profesional de la Información, 20(3), pp. 298-303. DOI: 10.3145/epi.2011.may.08. [ Links ]

GÉRTRUDIX, M., GERTRUDIS CASADO, M. C., ÁLVAREZ GARCÍA, S. (2016), “Consumption of public institutions’ open data by Spanish citizens”. El Profesional de la Información, 25(4), pp. 535-544. DOI: 10.3145/epi.2016.jul.03. [ Links ]

GIMÉNEZ CHORNET, V. (2012), “Acceso de los ciudadanos a los documentos como transparencia de la gestión pública”. El profesional de la información, septiembre-octubre, v. 21, n. 5, pp. 504-508. DOI: 10.3145/epi.2012.sep.09. [ Links ]

GRIMMELIKHUIJSEN, S., WELCH, E. W. (2012), “Developing and testing a theoretical framework for computer-mediated transparency of local governments”. Public Administration Review, 7 (4), pp. 562-571. DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02532.x. [ Links ]

GRIMMELIKHUIJSEN, S., PORUMBESCU, G., HONG, B., IM, T. (2013), “The effect of transparency on trust in government: a cross-national comparative experiment.” Public Administration Review 73 (4), pp. 575-586. DOI: 10.1111/puar.2013.73.issue-4. [ Links ]

HOOD, C., HEALD, D. (2006), “Transparency: the key to better governance?”. In Proceedings of the British Academy,135, Oxford, Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

HUIJBOOM, N., VAN DEN BROEK, T. (2011), “Open data: an international comparison of strategies”. European Journal of ePractice, 12(1), pp. 1-13. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/UN-DPADM/UNPAN046727.pdf [ Links ]

INNES, J. E., BOOHER, D. (2004), “Reframing public participation: strategies for the 21st century.” Planning Theory & Practice 5(4), pp. 419-436. DOI: 10.1080/1464935042000293170. [ Links ]

JAEGER, P. T., BERTOT, J. C. (2010), “Transparency and technological change: ensuring equal and sustained public access to government information”. Government Information Quarterly, 27, pp. 371-376. DOI: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.05.003. [ Links ]

JARMUZEK, M., ORLOWSKI, L. T., RADZIWILL, A. (2004), “Monetary policy transparency in the inflation targeting countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland”. CASE Studies and Analyses Working Paper, 281, pp. 1-32. DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.666102. [ Links ]

JORGE, S., et al. (2011), “Local government financial transparency in Portugal and Italy: a comparative exploratory study on its determinants”. 13th Biennial CIGAR Conference, Bridging Public Sector and Non-Profit Sector Accounting, Ghent, June 9-10. [ Links ]

KIM, S. (2010), “Collaborative leadership and local governance.” In R. O’Leary, D. M. Van Slyke, and S. Kim (eds.), The Future of Public Administration Around the World: The Minnowbrook Perspective, Washington, DC, Georgetown University Press, pp. 111-116. [ Links ]

KIM, S., LEE, J. (2012), “E-participation, transparency, and trust in local government”. Public Administration Review, 72(6), pp. 819-828. [ Links ]

KING, C. S., FELTEY, K. M., SUSEL, B. (1998), “The question of participation: toward authentic public participation in public administration.” Public Administration Review, 58(4), pp. 317-326. [ Links ]

LINDSTEDT, C., NAURIN, D. (2010), “Transparency is not enough: making transparency effective in reducing corruption.” International Political Science Review, 31(3), pp. 301-322. DOI: 10.1177/0192512110377602. [ Links ]

MANFREDI SÁNCHEZ, J. L., CORCOY RIUS, M., HERRANZ DE LA CASA, J. M. (2017), “Breaking news? Journalistic criteria in the publication of news on Spanish municipal websites (2011-2016)”. El profesional de la Información, 26(3), pp. 412-420. DOI: 10.3145/epi.2017.may.07. [ Links ]

MEIJER, A. J. (2003), “Transparent government: parliamentary and legal accountability in an information age.” Information Polity, 8(1-2), pp. 67-78. [ Links ]

MEIJER, A. J. (2009), “Understanding modern transparency.” International Review of Administrative Sciences, 75(2), pp. 255-269. DOI: 10.1177/0020852309104175. [ Links ]

MOLINA RODRÍGUEZ-NAVAS, P., SIMELIO SOLÀ, N., CORCOY RIUS, M. (2017), “Methodology for transparency evaluation: procedures and problems”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 818-831. DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1194en. [ Links ]

MOON, M. J. (2002), “The evolution of e-government among municipalities: rhetoric or reality?”. Public Administration Review, 62(4), pp. 424-433. DOI: 10.1111/puar.2002.62.issue-4. [ Links ]

MORENO SARDÀ, A., et al. (2013), “Infoparticip@: periodismo para la participación ciudadana en el control democrático. Criterios, metodologías y herramientas”. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 19(2), pp. 783-803. Available at https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/artpub/2013/129284/estsobmen_a2013v19n2p783.pdf [ Links ]

MORENO SARDÀ, A., MOLINA RODRÍGUEZ-NAVAS, P., SIMELIO SOLÀ, N. (2017), “The impact of legislation on the transparency in information published by local administrations”. El profesional de la Información, 26(3), pp. 370-380 Available at http://www.elprofesionaldelainformacion.com/contenidos/2017/may/03.pdf [ Links ]

MUNDA, G. (2004), “Social multi-criteria evaluation: methodological foundations and operational consequences.” European Journal of Operational Research 158, pp. 662-677. DOI: 10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00369-2. [ Links ]

NAVARRO-GALERA, A. (2014), “Transparency of sustainability information in local governments: English-speaking and nordic cross-country analysis”. Journal of Cleaner Production, 64, pp. 495-504. DOI: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.038. [ Links ]

NAVARRO-GALERA, A., et al. (2017), “Promoting sustainability transparency in european local governments: an empirical analysis based on administrative cultures”. Sustainability, 9(3), pp. 432-452. DOI: 10.3390/su9030432. [ Links ]

PINA, V., TORRES, L., ROYO, S. (2007), “Are ICTs improving transparency and accountability in the EU regional and local governments? An empirical study.” Public Administration, 85(2), pp. 449-472. DOI: 10.1111/padm.2007.85.issue-2. [ Links ]

PINA, V., TORRES, L., ROYO, S. (2009), “E-government evolution in EU local governments: a comparative perspective”. Online Information Review, 33(6), pp. 1137-1168. DOI: 10.1108/14684520911011052. [ Links ]

PINA, V., TORRES, L., ROYO, S. (2010), “Is e-government promoting convergence towards more accountable local governments?”. International Public Management Journal, 13(4), pp. 350-380. DOI: 10.1080/10967494.2010.524834. [ Links ]

PIOTROWSKI, S. J. (2010), “an argument for fully incorporating nonmission-based values into public administration.” In R. O’Leary, D. M. Van Slyke and S. Kim (eds.), The Future of Public Administration Around the World: The Minnowbrook Perspective, Washington, DC, Georgetown University Press, pp. 27-31. [ Links ]

PIOTROWSKI, S. J., BERTELLI, A. (2010), “Measuring municipal transparency.” 14th IRSPM Conference, Bern, April. [ Links ]

PIOTROWSKI, S. J., VAN RYZIN, G. G. (2007), “Citizen attitudes toward transparency in local government”. The American Review of Public Administration, 37(3), pp. 306-323. DOI: 10.1177/0275074006296777. [ Links ]

RIVERO MENÉNDEZ, J. A., MORA AGUDO, L., FLORES UREBA, S. (2007), “Un estudio de la rendición de cuentas a través del e-gobierno en la administración local española”. In Empresa global y mercados locales: XXI Congreso Anual AEDEM. Available at https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/2521491.pdf. [ Links ]

ROBERTS, A. (2006), Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age, New York, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

SÁNCHEZ LABELLA, M. I., SIMELIO, N., MORENO SARDÀ, A. (2017), “Web accessibility for people with disabilities in Spanish city councils”. Cuadernos.Info, 41, pp. 155-173. DOI: 10.7764/cdi.41.1061. [ Links ]

SIRAFI, Z. (2016), What Difficulties Present Themselves When Trying to Compare How Corrupt and Democratic Lobbying is in Different Countries? Comparative Study between Sweden and Slovenia. Bachelor thesis. Department of Political Sciences, Växjö (Sweden), Linnaeus University. [ Links ]

STEVENS, S. S. (1946), “On the theory of scales of measurement.” Science, 103(2684), pp. 677-680. DOI: 10.1126/science.103.2684.677. [ Links ]

TOLBERT, C. J., MOSSBERGER, K. (2006), “The effects of e-government on trust and confidence in government”. Public Administration Review, 66(3), pp. 354-369. DOI: 10.1111/puar.2006.66.issue-3. [ Links ]

TRANSPARÊNCIA E INTEGRIDADE ASSOCIAÇÃO CÍVICA (TIAC) (2017), Índice de Transparência Municipal. Apresentação e Indicadores, Novembro 2017, Ed. TRANSPARÊNCIA E INTEGRIDADE, ASSOCIAÇÃO CÍVICA. Available at https://transparencia.pt/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ITM_Apresentacao_e_Indicadores_2017.pdf . [ Links ]

TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL (2015), Local Governance Integrity: Principles and Standards, Berlin, Transparency International. [ Links ]

WELCH, E. W., HINNANT, C. C., MOON. M. J. (2005), “Linking citizen satisfaction with e-government and trust in government.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(3), pp. 371-391. DOI: 10.1093/jopart/mui021. [ Links ]

Received at 15-05-2018.

Accepted for publication at 12-06-2019.

[1] This article is the result of the research project Methods and Models of Information for the Monitoring of the Actions of Local Government Policy-makers and Accountability (CSO2015-64568-R), financed by the Secretary of State for Research, Development and Innovation, of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), within the State Program for Research, Development and Innovation Oriented at the Challenges of Society. Principal investigators: Dr Amparo Moreno Sardà and Dr Núria Simelio Solà.

[2] On the PISA program, see http://www.oecd.org/pisa/.

[3] Available at https://transparencia.pt.

[4] Available at http://mapainfoparticipa.com.

[5] Portugal has 308 municipalities, while Spain has 8,116 according to the National Institute of Statistics (INE), available at http://www.ine.es.

[6] Catalonia has 948 municipalities according to the National Institute of Statistics (INE), available at http://www.ine.es.

[7] The TIAC website can be found at https://transparencia.pt; Mapa Infoparticipa at http://mapainfoparticipa.com.

[8] Website available at https://www.transparency.org.

[9] In O que facemos [What we do], https://transparencia.pt/o-que-fazemos/.

[10] Available at Mapa Infoparticipa, Qué hacemos [“What we do”], http://mapainfoparticipa.com/index/home/6.

[11] Legislative Decree 2/2003, of April 28, approving the Consolidated Text of the Municipal and Local Regime Law of Catalonia, available at http://dogc.gencat.cat/es/pdogc_canals_interns/pdogc_resultats_fitxa/?action=fitxa&documentId=320821&language=ca_ES.

[12] Available at http://labcompublica.info/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/decaleg.pdf.

[13] Law 19/2013, of December 9, on transparency, access to public information and good governance, available at https://www.boe.es/buscar/doc.php?id=BOE-A-2015-470.

[14] Law 19/2014, of December 29, on transparency, access to public information and good governance. Autonomous Community of Catalonia. Available at http://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-470 .

[15] The table with the criteria for granting the Seals and other information can be found on the Mapa Infoparticipa website in the Infoparticipa Seals section available at http://www.mapainfoparticipa.com/index/home/7.

[16] For the correct monitoring of this section: the TIAC indicators have multi-level numbering while the LPCC indicators have a cardinal number.