Introduction

In the last decade, access to adequate and affordable housing has become a major concern in many European cities (Farha, 2019). The recent tourism boom and the emergence of the sharing economy have exacerbated the housing crisis in several tourist cities, jeopardising their ability to provide adequate and affordable housing for all (Lee, 2016; Novy, 2017). Most short-term rental services are mainly concentrated in a few specific neighbourhoods in large cities (tourist attractions, business centres, museums, religious sites, playgrounds, historic centres etc.), creating spatial inequalities, driving property prices up and negatively affecting local liveability (Horn and Merante, 2017; Garha, 2021). These services can exclude long-term tenants from their traditional neighbourhoods by reducing supply and increasing monthly rents for available long-term rentals (Samaan, 2015). This exclusion of the local population can have dire consequences for community life in certain neighbourhoods of tourist cities. One of the main global players in the short-term rental business, which has a very strong impact on the housing market in Barcelona and Lisbon, is ‘Airbnb’.

Airbnb started as a peer-to-peer platform in San Francisco in 2008, allowing people to rent out their underutilised rooms or homes to tourists or other short-term visitors through online transactions. It currently has more than 5.6 million listings in over 100,000 cities in 220 countries and regions around the world. According to data from December 2019, on average, more than 2 million people stay on Airbnb per night (Airbnb, 2020. Over the last decade, following the success of Airbnb, many other short-term rental services have emerged around the world. Although, Airbnb remains the largest service provider in the short-term rental business, with almost twice as many listings as its closest competitors (e. g. Homeaway, Holidu, and Housetrip). The platform functions as a mediator and charges a designated fee for each successful booking. Airbnb’s success can be judged by the fact that it currently earns more money than the world’s most famous hotel chains, such as Hilton and Marriot international (Molla, 2019). Its self-proclaimed mission is ‘to create a world where people can belong through healthy travel that is local, authentic, diverse, inclusive, and sustainable. Airbnb uniquely leverages technology to economically empower millions of people around the world to unlock and monetise their spaces, passions, and talents and become hospitality entrepreneurs’ (Airbnb, 2020). However, for many researchers, policy makers, community groups, and housing activists around the world, the company’s activity has devastating effects on adequate and affordable housing in traditional neighbourhoods in major tourist cities (Wachsmuth et al., 2017; Wieditz, 2017; Lee, 2016; Samaan, 2015). Moreover, since its inception, Airbnb’s business model has remained controversial, as it ignores housing and land use rules and regulations in almost all cities where it operates (Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018).

Previous studies have shown that Airbnb had a far-reaching impact on the housing markets of host cities. For some researchers, short-term rental services such as Airbnb offer two main benefits: additional income for hosts and more short-term accommodation options with additional amenities for visitors (Shabrina et al., 2019). However, others argue that the comparatively higher income potential of short-term rentals led to the displacement of local residents (Cocola-Gant, 2016; Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018) and exacerbate housing affordability problems in major tourist cities around the world (Lee, 2016; Horn and Merante, 2017; Barron et al., 2017).

This article analyses the impact of Airbnb on the housing market in two of southern Europe’s leading tourist cities, Barcelona and Lisbon. Both cities receive more than 9 million and 4.5 million overnight tourists per year, respectively (Statista, 2020), making them the most mature tourist destinations and a perfect market for Airbnb in Southern Europe. This large influx of visitors, together with the emergence of short-term rental services, has a major impact on the supply and price of housing in both cities. In previous studies on the expansion of Airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon, several authors have discussed its impact on the tourism and hotel industry (Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Cocola-Gant et al., 2021), the quality of life in cities (Cocola-Gant and Gago, 2019) and the commercialisation of residential housing (Lestegás et al., 2018; Lestegás et al., 2019; García-López et al., 2019) and recently on spatial inequalities (Garha, 2021; Garha and Azevedo, 2021a). However, its effect on the price and supply of the long-term rental market remains to be quantitatively assessed.

Our hypotheses are that: i) the spread of Airbnb has a considerable impact on the supply and price of long-term rentals in both cities; and ii) the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the growth of Airbnb and reduced the burden of the housing market in Barcelona and Lisbon. Accordingly, using data extracted from the Inside Airbnb website, the Idealista website, and the 2011 Census of Spain and Portugal, this article starts by characterising the typology of listings, hosts and accommodations offered on Airbnb in both cities. Then, testing our first hypothesis, it estimates the number of long-term rentals lost to Airbnb in different neighbourhoods in both cities, which in turn affects their supply in the local housing market. Next, it measures the potential rent increase created by Airbnb, which ultimately can affect housing affordability in certain neighbourhoods in both cities. Finally, testing our second hypothesis, the paper examines the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the spread and characteristics of Airbnb activity in both cities and compares the growth of Airbnb and its impact on the housing market in both cities.

The article is structured as follows. ‘Literature review’ presents a review of existing studies exploring the relationship between Airbnb and the housing market. ‘Data sources and methodology’ describes the data sources and methods used in this study. ‘Airbnb and housing market in Lisbon and Barcelona’ analyses the impact of Airbnb on the housing market in Barcelona and Lisbon. ‘The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon’ examines the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on Airbnb activity in both cities. Finally, ‘Conclusions’ presents the concluding remarks and discusses the impact of Airbnb on the housing market and the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on Airbnb in the two southern European cities.

Literature review

Over the last decade, Airbnb has become the biggest competitor in the short-term rental market (Larpin et al., 2019), with a large number of commercial listings of entire flats offered by multi-hosts. Currently, ‘the majority of Airbnb listings, in different cities, are entire homes, many of which are rented year-round, becoming de facto hotels’ (Chamusca et al., 2019, p. 3). This rampant commercialisation of Airbnb, which has evolved from a home-sharing platform to a commercial platform for short-term rentals, has raised questions about the very nature and primary purpose of this service.

Numerous studies have highlighted the social impacts of the Airbnb phenomenon on urban populations, especially in terms of the distortion of the housing market (Lee, 2016; Horn and Merante, 2017), the displacement of the local population from their traditional neighbourhoods (Dudas et al., 2017), the loss of traditional short-term rentals and the hotel industry (Guttentag, 2015; Guttentag and Smith, 2017; Oskam and Boswijk, 2016; Zervas et al., 2017), and tourism-related gentrification of urban districts (Oppilard, 2017). Researchers studying the impact of Airbnb on housing have found that it has created a new category of rental housing, short-term rentals, which fill the gap between traditional residential rental housing and hotel accommodation (Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018; Cocola-Gant et al., 2021). Proponents of Airbnb and other short-term rental services claim that these services have made it easier and more lucrative for small landlords to rent out their underutilised rooms and homes that supplement their monthly rental income and bring tourism to traditionally non-touristy neighbourhoods (Gunter, 2018). According to them, it empowers people to exploit the full potential of their properties, increases tourism-related economic benefits, and generates additional income for businesses in these neighbourhoods. However, critics claim that these services take away already scarce long-term rentals in large cities, increase rents for the remaining long-term rentals, transform residential buildings into commercial assets, create precarious service sector jobs, diminish the quality of life for local residents, violate local zoning and other ordinances, and exclude the indigenous population from their traditional neighbourhoods (Samaan, 2015; Cocola-Gant, 2016; Fuentes et al., 2019).

Airbnb has a considerable impact on the supply of long-term rentals in the cities where it operates. As Airbnb uses residential areas, which are traditionally designed to serve the housing needs of the local population, it decreases the supply of long-term rentals in local housing markets (Barron et al., 2019). Horn and Merante (2017) demonstrated in their study that Airbnb has led to a reduction in the supply of housing available for long-term residents in Boston. Similarly, Schäfer and Braun (2016) have shown how the misuse of the Airbnb platform by multi-hosts in Berlin is one of the main reasons behind the housing crisis in Berlin.

The effect of Airbnb on the emergence of the ‘rent-gap’ has received much attention from researchers in the last decade (Wachsmuth and Weisler, 2018). Since Airbnb functions as a mechanism to produce new income streams for homeowners, it also increases the average monthly rent of houses in the areas where it operates. Its effect is also mediated by culture, as the rent increases first in those areas that are close to the city centre and to different points of attraction. In some recent studies, authors have highlighted the role of Airbnb in accelerating the process of touristification of residential areas, which in turn exacerbates the shortage of long-term rentals and increases residential rents in different tourist cities (Cocola-Gant and Gago, 2019). Lee (2016) in his research showed that an increase in the supply of short-term rentals raises rents in the long-term rental market and affects housing affordability for local residents. Coyla and Yeung (2016) in their study of Airbnb activity in London showed a positive impact of the arrival of Airbnb on rental prices in the city. Similarly, Ayouba et al. (2019) in their study of eight French cities showed the impact of Airbnb on the increase of long-term rentals in Lyon, Montpellier, and Paris. Sheppard and Udell (2018) in their study on New York City showed how the entry of Airbnb has increased housing prices in the city. Barron et al. (2017), in their study of 100 US cities, found that, especially in neighbourhoods with a lot of rented housing, increased Airbnb activity translated into higher rents for long-term residents. Despite previous evidence on the impacts of Airbnb activity on the housing market, the majority of studies have focused on studying one city or several cities in one country, with some exceptions (e.g. Coyla and Yeung, 2016).

In this study, we focus on two European cities - Barcelona and Lisbon - with a twofold objective: 1) to explore the impact of Airbnb on the housing market (supply and rent) and 2) to examine the effect of COVID-19 on the Airbnb activity (number of listings, types of accommodation, and composition of hosts) in both cities. These cities have overheated and complexified housing markets, where it is increasingly difficult for low-income groups to access adequate housing at affordable prices (Blanco-Romero et al., 2018, Antunes and Seixas, 2020). Barcelona is the financial capital and second most populous city in Spain. It was one of the first cities in Spain where Airbnb started its activity in 2009. The large influx of tourists and short-term visitors makes it a perfect market for Airbnb. Also, Lisbon, which is the capital and one of the main tourist cities in Portugal, has the highest number of Airbnb listings in Portugal. The number of Airbnb listings in both cities has increased considerably after the global financial crisis of 2007-2012. Although Barcelona has more than three times the population of Lisbon, the number of Airbnb listings is very close in both cities, partly because the Portuguese economic recovery has been driven by increased tourism. The choice of two cities with a similar housing system, but with different policies regarding Airbnb activity (more restrictive in Barcelona than Lisbon), makes this study more relevant to examine the impact of policy changes.

Airbnb’s business is largely based on the short-term movement of people from one place to another, for work or tourism. Thus, closures and restrictions imposed on the movement of people in different countries due to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the growth of Airbnb worldwide (Bugalski, 2020; Dolnicar and Zare, 2020). Barcelona and Lisbon are no exception, justifying a closer examination of the effects of the pandemic on Airbnb activity. Still, restrictions are in place in both cities and the future of Airbnb depends on the success of ongoing vaccination programmes around the world.

Data sources and methodology

Data sources

In this article, we combine data from three sources to study the impact of Airbnb on the housing markets of Barcelona and Lisbon. Data on Airbnb listings are obtained from Murray Cox’s Inside Airbnb website. This website periodically performs web-scraping of the official Airbnb website and makes available snapshots of Airbnb listings in major cities around the world. We used all Airbnb listings, which have information on rental accommodations that were available for booking in September 2019 and December 2020, in Barcelona and Lisbon. Each listing has attributes such as host and room ID, neighbourhood name, geographic location, room type, accommodation details, availability, price, and number of reviews posted by users on the website.

Data on the existing housing stock in Barcelona and Lisbon are obtained from the 2011 Population and Housing Census of Spain and Portugal.1 These data provide information on the number, size, quality, and types of residential apartments available in different neighbourhoods in both cities. Data on the median price of long-term rentals in each neighbourhood are obtained from the Idealista website,2 which is one of the most widely used internet platforms for long-term rentals in Barcelona and Lisbon.

Methodology

According to our hypotheses, we use different measures to estimate the impact of Airbnb on the housing market in Barcelona and Lisbon. To assess the impact of Airbnb on housing supply, we classify all listings into two categories: casual listings and commercial listings. We use the number of days a unit is booked or available for booking to identify and estimate the number of commercial listings. All listings where entire flats are available for more than 60 days per year are defined as commercial listings. This rules out most short-term occasional rental scenarios, such as a landlord taking advantage of a one-month gap between long-term tenants, or a family going on a one-month summer holiday (Wachsmuth et al. 2017). In contrast, all other listings with an availability period of less than 60 days are considered casual listings.

Similarly, to study the profile of Airbnb hosts, based on the total number of listings posted by an individual or company on the platform, we classify all Airbnb hosts into two categories: ordinary-hosts and multi-hosts. Ordinary-hosts are those who occasionally make their residences available for short-term rental to earn supplementary income. This includes hosts who rent out their entire home or rooms on a short-term basis when they are away for a weekend, holiday or trip. In contrast, multi-hosts are those who have more than three listings with their user ID on the Airbnb platform. As these hosts do not rent their empty flats in the long-term rental market, they affect the supply of long-term rentals in the housing market. We use the unique Airbnb user ID number to identify and count the number of multi-hosts. When the same user ID number is associated with more than three complete flat listings, we consider it a multi-host.

The number of housing units lost to Airbnb is calculated by subtracting the number of commercial listings of full flats in a neighbourhood from the total number of housing units available in that neighbourhood. The proportion of housing units lost to Airbnb shows the impact of Airbnb on the supply of long-term rentals, which in turn can affect the average monthly rent in different neighbourhoods. The potential rental-income increase created by Airbnb is calculated by measuring the difference between the actual average monthly rent of a long-term rental in a neighbourhood and the potential rental income can be earned by a short-term host on Airbnb. To calculate the potential revenue from Airbnb, we use the occupancy threshold of 20 days per month.

Then, to study the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Airbnb in both cities, we compared the situation of the housing market and Airbnb in both cities before (September 2019) and during the pandemic (December 2020) using three measures: the total number of Airbnb listings, the types of accommodation offered, and the composition of hosts.

One final note is worth mentioning: this article compares two moments in time (September 2019 and December 2020), so it is not possible to say anything about long-term trends in the housing market and Airbnb activity in both cities. However, it is possible to identify different interpretations of the results without establishing causal relationships.

Airbnb and housing market in Lisbon and Barcelona

Airbnb transforms residential flats into short-term rentals, which has a considerable impact on the housing market in Barcelona and Lisbon. In September 2019, Barcelona and Lisbon had the highest number of Airbnb listings in Spain and Portugal, i. e. 20,404 and 18,277 listings, respectively. Most of these were located in the historic central parts of both cities, which have a large number of tourist attractions and a high concentration of commercial activities. Prior to the arrival of Airbnb, these historic neighbourhoods had a number of housing-related problems, stemming from poor conditions and lack of basic services (such as lifts, air conditioning, and heating systems) in residential buildings. A large part of the housing stock was unfit for healthy living due to neglect by the public administration and lack of investment in the refurbishment of residential buildings, resulting in a shortage of suitable housing and a high proportion of empty and largely abandoned housing in both cities.

Airbnb’s expansion in these neighbourhoods coincided with several urban redevelopment schemes, which allowed homeowners to rehabilitate their abandoned houses in both cities. In Barcelona, taking advantage of public funding and subsidies, many homeowners refurbished their abandoned houses. But instead of putting them on the long-term rental market, they converted them into short-term rentals to rent them out on Airbnb. Some of them evicted long-term tenants to refurnish their houses and replace them with tourists. In Lisbon, the main objective of the redevelopment plans was to get rid of abandoned housing stock and attract more tourists to central areas, which facilitated Airbnb’s expansion but did not benefit the resident population. The expansion of Airbnb in both cities raised a new demand for housing (short-term rentals), creating new housing problems and exacerbating existing ones in both cities.

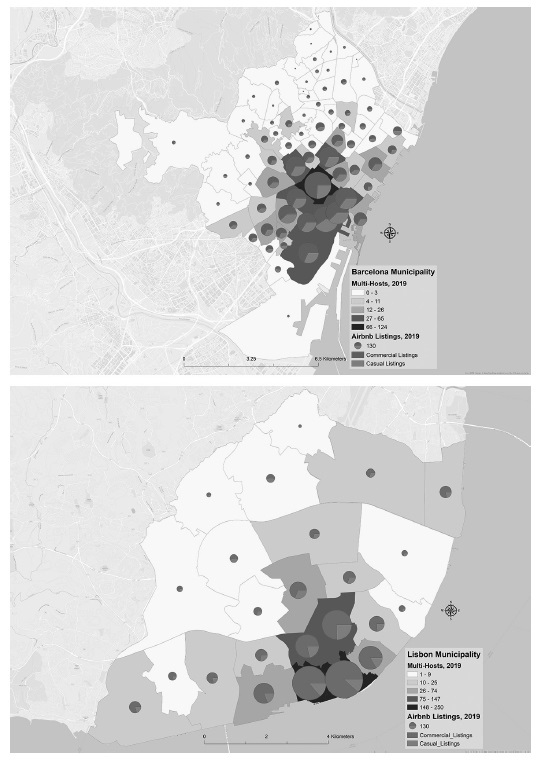

Given that the demand for accommodation on Airbnb is affected by various characteristics of the housing stock, it is important to explore the typology of accommodation offered on Airbnb in both cities to measure its impact on the housing market. Over the last decade, Airbnb has diversified the types of accommodation it offers. This has helped Airbnb expand its business around the world, but has turned residential flats into commercial assets, which can be rented out in whole or in parts to earn additional income. In 2019, 44.4% of total listings in Barcelona were whole houses/apartments, 51% private rooms, 3.8% hotel rooms, and 0.8% shared rooms. The neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample (1208), Raval (646), Sagrada Familia (604), Sant Pere, Santa Caterina I la Ribera, (592), and Poble Sec (565) had the highest number of whole houses/apartments in their Airbnb listings. However, the neighbourhoods of Vila Olímpica del Poblenou (61.6%), Diagonal Mar i el Front Maritim del Poblenou (58.8%), Barceloneta (58.3%), and Putxet i el Farro have the highest proportion of whole houses/apartments in their total Airbnb listings. In terms of private rooms, the neighbourhoods of Raval (1,059, 59.9%), Barri Gotic (785, 57.4%), Dreta de l’Eixample (644, 31.1%), Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera (611, 48.9%), and Nova Esquerra de l’Eixample (579, 64.3%) have the highest proportion of private rooms in total listings (Fig. 1). All of these neighbourhoods have many tourist attractions and business centres that attract a large number of short-term visitors annually and make them a perfect market for Airbnb.

In Lisbon, the proportion of whole houses/apartments in the total number of listings was much higher than in Barcelona (73.7%), followed by 22.5% of private rooms, 2.6% of hotel rooms, and 1.3% of shared rooms. The parishes of Santa Maria Maior (3,286), Misericórdia (2,651), Arroios (1,363), São Vicente (1,269), and Santo António (1,089) have the highest number of whole houses/apartments in their Airbnb listings, which may be related to the fact that in this area there was a high proportion of vacant dwellings. All these parishes make up the historic centre of Lisbon, which has a large number of tourist attractions and other places of interest for short-term visitors. In addition, also very well-located areas, the parishes of Parque das Nações (83.5%), Ajuda (79.6%), Estrela (78.7%), and Alcântara (76.4%) had the most significant proportion of whole houses/apartments in their total Airbnb listings. In the private room category, the parishes of Arroios (903, 38.2%), Misericórdia (394, 12.7%), Santa Maria Maior (377, 9.9%), Avenidas Novas (346, 44.9%), and Santo António (332, 22.1%) had the highest proportion of private rooms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 The total population and the types of accommodations offered on Airbnb in each neighbourhood of Barcelona and Lisbon, 2019. Source: own elaboration, data from municipal registers 2019, Inside Airbnb, September 2019.

Confirming our first hypothesis, in relation to the housing supply, the large proportion of whole houses/apartments on Airbnb shows its impact on reducing the supply for long-term rentals in the housing market both in Barcelona and in Lisbon. Most of these flats, which are now available to short-term visitors, were available to long-term renters or vacant before the arrival of Airbnb. Compared to Barcelona, the higher proportion of Airbnb listings in relation to population and of whole houses/apartments in the total number of Airbnb listings in Lisbon makes it more vulnerable to the adverse effects of Airbnb on the housing market.

Commercial listings, multi-hosts, and long-term rentals lost to airbnb

Airbnb’s impact on the supply of long-term rentals in both cities can be measured by the presence of commercial listings, multi-hosts, and the proportion of long-term rentals lost to Airbnb in different neighbourhoods in both cities. As a home-sharing platform, Airbnb began its activity for ordinary hosts, who were encouraged to rent out their underutilised rooms to short-term visitors in exchange for a daily rent. However, it quickly evolved into a commercial service, specialising in short-term rentals and a major competitor to the long-term rental market and the hotel industry. With a very small investment, it allows homeowners in large cities to convert their empty flats into short-term rentals, which are then rented out to tourists and other short-term visitors for a comparatively higher rent than the average long-term rent in the neighbourhood. This ease of doing business has made Airbnb a lucrative business for landlords, but has altered the balance of supply and demand for long-term rentals in local housing markets.

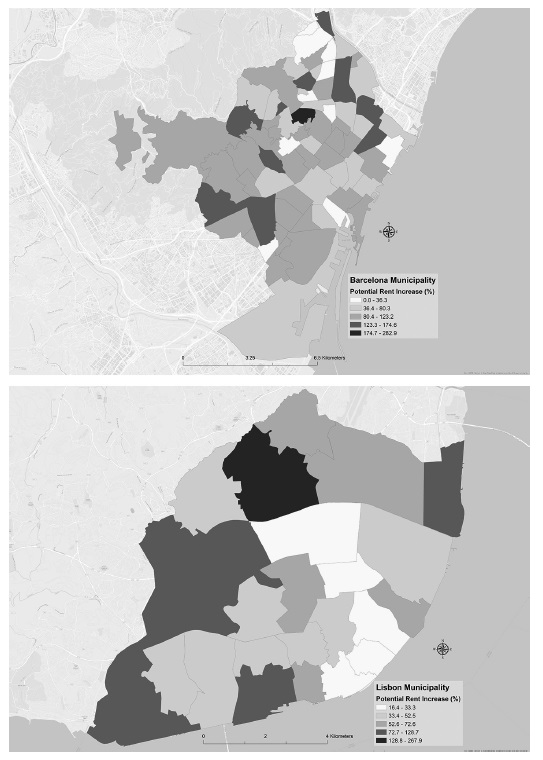

In Barcelona and Lisbon, the number of commercial listings has increased rapidly over the last decade. In 2019, the share of commercial listings in Barcelona and Lisbon was 64.9% and 80.2%, respectively. The majority of these were located in the central historic districts of both cities. In Barcelona, the central neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample (66.2%), Raval (58.2%), Barri Gotic (61.1%), Sant Pere, Santa Caterina i la Ribera (63.2%), and Poble Sec (66.7%) had a significantly higher proportion of commercial listings. Similarly, in Lisbon, the parishes of Santa Maria Maior (88.4%), Misericórdia (86.3%), Arroios (75.2%), São Vicente (83.3%), and Santo António (78.6%) had a significant proportion of commercial listings (Fig. 2). This rampant commercialisation of Airbnb in both cities has exacerbated the shortage of suitable and affordable housing for the long-term renters from the local population. Most of these commercial listings are owned and operated by large real estate firms and foreign investors who have brought in multiple properties in the downtown neighbourhoods of both cities to rent to tourists (Cocola-Gant and Gago, 2019), which in turn has created a special class of multi-hosts who are the real beneficiaries of Airbnb.

Figure 2 The proportion of commercial listings and multi-hosts in different neighbourhoods of Barcelona and parishes of Lisbon, 2019. Source: own elaboration, data from Inside Airbnb.

In this study, we consider as multi-hosts all persons or companies that have more than three listings with the same user ID number. It is reasonable to assume that these multi-hosts do not share houses, but rent entire flats or private rooms to short-term visitors. In 2019, the total number of multi-hosts in Barcelona was 775 (6.3% of all hosts). However, they owned and managed 28.1% of the total number of listings in Barcelona. Most of them are concentrated in the neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample (124, 14.6%), Barri Gotic (65, 8.6%), l’Antiga Esquerra de l’Eixample (65, 11%), Raval (64, 5.8%), Sant Antoni (55, 9.1%), and Sagrada Familia (50, 8.1%). The total number of multi-hosts in Lisbon (1,035, 10.9%) was even higher than in Barcelona. In 2019, they owned and managed 41.5% of the total number of listings in Lisbon. The parishes of Santa Maria Maior (250, 14.9%), Misericórdia (189, 13.5%), Avenidas Novas (48, 13.3%), Arroios (147, 12.5%), Santo António (92, 12.3%), and Areeiro (23, 11.8%) had the highest proportion of multi-hosts (Fig. 2). Compared to Barcelona, the large proportion of multi-hosts in Lisbon shows that the Airbnb business is concentrated in the hands of a few owners, who rent out their empty homes to short-term visitors to maximise their rental income. This could be related to the existence of a housing surplus in the period before the global financial crisis of 2007-2012 that severely affected the Portuguese housing market and the economy in general (Garha and Azevedo, 2021b).

The high proportion of multi-hosts in some central neighbourhoods translates into the large number of long-term rentals lost to Airbnb. In 2019, the number of long-term rentals lost to Airbnb in Barcelona was 7,595, 0.9% of all available housing in the city. The neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample (1031, 4.1%), Raval (531, 2.3%), Poble Sec (502, 2.7%), Sant Pere, Santa Caterina I la Ribera (496, 3. 4%), Barri Gòtic (447, 4.3%), Barceloneta (218, 2.4%), and Vila Olímpica del Poblenou (109, 2.3%) lost the most housing units to Airbnb. In contrast, the peripheral neighbourhoods of Guineueta, Prosperitat, La Turo de la Peira, Horta, and Verdun had less than 0.1% of homes lost to Airbnb. In Lisbon, the number of dwellings lost to Airbnb was 13,403, representing 4.1% of all available housing in the city. The parishes of Santa Maria Maior (3,332, 31.4%), Misericórdia (2,650, 26.3%), Arroios (1,375, 7.9%), São Vicente (1,213, 12.3%), Santo António (1,088, 13.2%), Estrela (882, 7.4%), and Penha de França (372, 2.1%) had the highest number of homes in this situation. In contrast, the parishes of Santa Clara, Benfica, Carnide, and Marvila were the least affected, i. e., below 1% (Fig. 3). The loss of long-term rentals to Airbnb reduces the supply of affordable housing, which particularly affects socio-economically vulnerable groups, such as young adults who want to leave their parents’ home and form new households and migrant workers who want to start their lives in the host country (Garha and Azevedo, 2021b).

Potential rent increase in Barcelona and Lisbon

Airbnb also had a very significant impact on the average monthly rent in the neighbourhoods where it operates (Yrigoy, 2019). The decline in the supply of long-term rentals in the rental market is accompanied by a sharp rise in housing rents in both cities. Since 2013, rental prices in Barcelona have risen by 36.4%, with the monthly average reaching an all-time high of €929.60 in 2018, and sales prices have risen by 38.1% for newly built homes and 50.3% for second-hand homes between 2013 and 2018 (Trilla and Alcalá, 2019). Similarly, in Lisbon, the average monthly rent has doubled to €1000 and the average selling price of housing has increased by 26% between 2011 and 2015 (Lestegás et al., 2018). According to recent estimates by INE Portugal, the average price of housing in the Lisbon metropolitan area has increased from 150.4 thousand in 2009 to 209.4 thousand in 2020 (INE Portugal, 2021a). The median price of new rental contracts has increased by 24.3% in Lisbon between 2017 and 2019 (INE Portugal, 2021b). From the available data, it is not possible to say how much of these increases in rental price is due to the spread of Airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon, but it has certainly played an important role in decreasing the supply of long-term rentals in some central neighbourhoods. The possibility of renting flats to short-term visitors at a higher price has increased the potential income that owners can earn from their empty homes. This increase in potential revenue has helped Airbnb’s expansion in both cities.

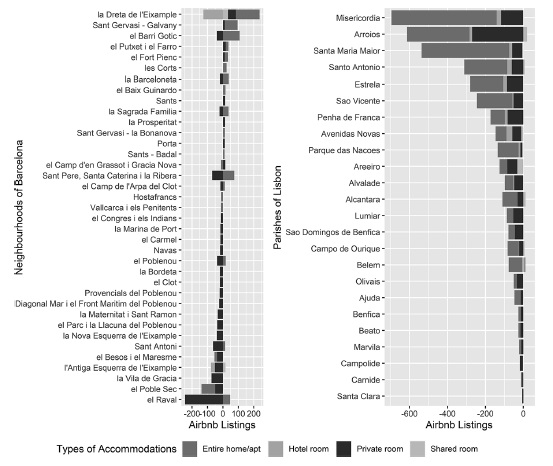

Currently, homeowners in Barcelona and Lisbon can earn on average 92.7% and 68.1% more rental income, respectively, by renting out their flats to short-term visitors on Airbnb, as opposed to renting them to long-term tenants on the Idealista website. This difference in potential income is not identical across neighbourhoods in both cities. In Barcelona, the neighbourhoods of Marina del Prat Vermell (282.9%), La Salut (174.6%), Hostafrancs (171.6%), Vilapicina i la Torre Llobeta (163.6%), and Vallvidrera, el Tibidabo i les Planes (151. 2%) have registered the highest potential increase in rental income and the neighbourhoods of Baro de Viver (3.5%), Pedralbes (13.9%), Navas (26.5%), Vall d’Hebron (31.5%), and Montbau (32.4%) have registered the lowest potential increase in rental income created by Airbnb. Likewise, in Lisbon the parishes of Lumiar (267.9%), Belém (128.8%), Parque das Nações (103.9%), Benfica (94.2%), and São Domingos de Benfica (91.3%) have witnessed the highest potential increase in rental income and the parishes of Alvalade (16.4%), Penha de França (24.8%), Santa Maria Maior (26.3%), Areeiro (30.3%), and São Vicente (33.3%) registered the lowest potential increase in rental income (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 Potential rent increase caused by Airbnb in different neighbourhoods of Barcelona and parishes of Lisbon, 2019. Source: own elaboration, data from Inside Airbnb and Idealista website.

From these results, we can show that in neighbourhoods where the average monthly rents were lower than the city average, Airbnb had created a higher potential increase in rental income than in the other neighbourhoods. This increase in potential rental income had raised monthly rents in both cities and contributed to the expulsion of the local population from their traditional neighbourhoods. Today, in Barcelona and Lisbon, there are a large number of residents who cannot afford to pay the current rent and who will be forced to leave their homes and neighbourhoods after the end of their current rental contracts, which will have a number of negative consequences for community life in the central neighbourhoods of both cities.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon

The COVID-19 pandemic has a considerable impact on the supply and demand for Airbnb accommodations worldwide. The collapse of the travel and tourism industry induced by the lockdowns also slowed down Airbnb’s growth in Barcelona and Lisbon. In both cities, the recent pandemic has affected the number of total listings, the types of listings and hosts, the number of accommodation units lost to Airbnb, and the potential rental income obtained from Airbnb in different neighbourhoods.

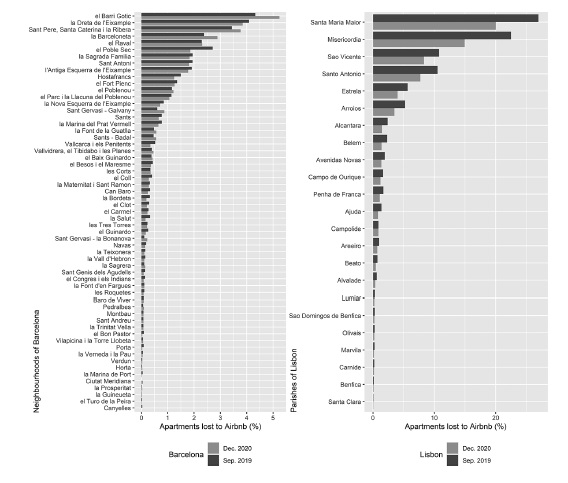

Since the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, the total number of Airbnb listings in Barcelona and Lisbon has decreased from 20,404 and 18,277 in September 2019 to 19,641 and 14,332 in December 2020, respectively. Compared to Barcelona (3.7%), the drop in the number of listings was much larger in Lisbon (21.6%), where almost one in five listings has been removed from the platform. This sharp decline in the number of listings in a relatively short period of one year shows that the pandemic hit Airbnb’s business hard in both cities. In Barcelona, the impact of the pandemic is very different in different neighbourhoods. The neighbourhoods of Raval (-236), Poble Sec (-149), Vila de Gracia (-102), Sant Antoni (-80), and Besós i el Marisme (-63) have seen a significant drop in the number of Airbnb listings, which is an expected result of the pandemic. However, on the contrary, the neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample (112), Sant Gervasi-Galvany (85), Barri Gotic (52), and Putxet i el Farro (37) had registered a small increase in the number of total listings, which was not expected. It may be due to the increasing demand for full flats instead of private or shared rooms, where social distancing was not possible. In Lisbon, the parishes of Misericórdia (-695), Arroios (-594), Santa Maria Maior (-536), Santo António (-305), and Estrela (-280) had lost the largest number of listings, while the parishes of Santa Clara (-4), Carnide (-13), Campolide (-19), Marvila (-21), and Benfica (-26) had the smallest drop in the number of total listings. A small part of this decline may be associated with new laws enacted by public authorities to curb the growth of Airbnb in both cities, but with the available data it is not possible to differentiate what percentage of the decline can be attributed to these regulatory changes.

In addition to the decline in the total number of listings, the COVID-19 pandemic has also affected the types of accommodation offered on Airbnb. In Barcelona, the largest decrease is registered in the number of private rooms (-906 listings), at the same time, the number of listings of entire houses/apartments has increased considerably in some central neighbourhoods (+543 listings). In Barcelona, the central Raval neighbourhood has lost the highest number of listings for private rooms. Meanwhile, the neighbourhoods of Dreta de l’Eixample, Barri Gotic, and Sant Gervasi-Galvany have gained the highest number of listings for entire houses/apartments. This shows that the main idea of Airbnb - sharing a house with others - has failed in Barcelona due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Barcelona hosts are unwilling to share their homes with strangers due to the risk of COVID-19 infection. However, the number of listings of entire houses/apartments on Airbnb, where the risk of infection is low, has continued to increase. Contrary to this trend, in Lisbon, the number of all types of accommodation offered on Airbnb has decreased, with a small exception of shared rooms in the parishes of Arroios and Alcântara (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 Typologies of accommodations offered on Airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon, 2019-2020. Source: own elaboration, data from Inside Airbnb, September 2019 and December 2020.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also affected the composition of hosts in both cities. In Barcelona, the number of multi-hosts (775) has remained constant, with some small changes in central neighbourhoods. However, the number of casual hosts has decreased from 11,612 in September 2019 to 11,112 in December 2020. Thus, in Barcelona, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected casual-hosts more than multi-hosts, who are commercial users and maintain their places on the platform, hoping that the situation will improve. In Lisbon, the number of both multi- and casual-hosts has decreased (from 1,035 and 8,493 in September 2019 to 815 and 6,676 in December 2020, respectively). This shows that, compared to Barcelona (4.3%), Lisbon (21.3%) has lost a higher proportion of hosts in the last year (Fig. 6). Given the failure of a municipal programme put in place to encourage landlords to switch their homes from the short-term to the long-term market, it appears that landlords may prefer to do short-term contracts (6-12 months) during the pandemic period and then return to the short-term business.

Figure 6 Airbnb hosts in Barcelona and Lisbon, 2019-2020. Source: own elaboration, data from Inside Airbnb, September 2019 and December 2020.

Confirming our second hypothesis, the fall in Airbnb activity in the last year has released some of the burden of the housing markets in both cities. The number of homes lost to Airbnb in Barcelona and Lisbon has fallen from 6,480 and 11,280 in September 2019 to 6,268 and 8,029 in December 2020, respectively. In Lisbon, all parishes have registered a decrease in the number of accommodations offered on Airbnb, however, in Barcelona some neighbourhoods, such as Barri Gotic, Sant Pere, Santa Cateina i la Ribera, and Barceloneta, have seen an increase in the number of homes lost to Airbnb. This may be due to increased demand for whole flats rather than private or shared rooms (Fig. 7).

Figure 7 Housing units lost to Airbnb, 2019-2020. Source: own elaboration, data from Inside Airbnb, September 2019 and December 2020; Census 2011.

The sudden drop in supply and demand for Airbnb accommodation has also affected the potential rental income of Airbnb hosts in both cities. Over the last year, out of a total of seventy-two neighbourhoods in Barcelona, potential rental income has fallen in fifty-five neighbourhoods, with a maximum drop recorded in La Salut (-121%), Hostafrancs (-103%), Turo de la Peira (-97%), and Besos I el Maresma (-94%). However, the rest of the neighbourhoods have recorded an increase in potential rental income, with the maximum increase recorded in Pedralbes (247%), la Maternitat i Sant Ramon (137%), Sant Gervasi-Galvany (101%), and la Dreta de l’Eixample (72%). This change in potential rental income is directly associated with a decrease in demand for Airbnb in the peripheral neighbourhoods and a small increase in demand for full flats in the central neighbourhoods of Barcelona. Likewise, fifteen of Lisbon’s twenty-four parishes have recorded a decrease in potential rental income, with the maximum decrease recorded in Avenidas Novas (-50%), Benfica (-49%), Misercórdia (-40%), and Estrela (-38%). The rest of the parishes recorded an increase in potential rental income, with a maximum increase in Santa Clara (65%), Lumiar (39%), Areeiro (30%), and Belém (13%). This decrease in Airbnb’s potential rental income may contribute to the return of housing to long-term rentals, which were snatched away by Airbnb in the last decade. However, it is still too early to know how the situation will evolve in the coming months and years.

Conclusions

After analysing Airbnb activity in Barcelona and Lisbon, we can conclude that there is clear evidence that the concentration of Airbnb listings in historic downtown neighbourhoods has had a number of consequences for the availability and affordability of long-term rentals in the central areas of both cities, such as a shortage of long-term rentals and a sudden increase in housing rents, which may lead to the displacement of poor local people from their traditional neighbourhoods. Airbnb affects the housing market in two ways. On the one hand, it reduces the supply of long-term rentals by transforming them into short-term rentals and, on the other hand, it increases the average rent for housing by creating a gap between the potential income from long-term and short-term rentals in the neighbourhoods where it operates.

Airbnb started its activity with the idea of sharing homes with short-term visitors to earn extra income. However, the accommodations offered on Airbnb have diversified over the last decade and it has now become a competitor in the long-term housing market in both cities. Currently, a significant number of Airbnb listings consist of entire flats, which diminishes the supply of long-term rentals in the housing markets of both cities. The composition of Airbnb hosts has also changed significantly. Most of the flats listed on Airbnb are owned by multi-hosts (individuals or companies) who use this platform to rent out entire flats or blocks of flats to multiply their rental income. The presence of a large number of multi-hosts demonstrates the commercialisation of Airbnb in both cities, which in turn increases the proportion of homes lost to Airbnb.

The rental increase created by Airbnb in different neighbourhoods in both cities exacerbates the problem of affordability of long-term rentals in both cities. In turn, it leads to the displacement of socio-economically vulnerable groups (elderly, youth, single-parent families, and immigrants) from traditional neighbourhoods, which has several negative consequences for community life and the liveability of people in both cities. The replacement of long-term tenants by tourists may alter the demographic, social, cultural, economic, and political composition of neighbourhoods and destroy the community life of residents, who often feel powerless in the face of these large multinationals.

In the last decade, local governments have taken some drastic measures to curb Airbnb’s expansion in both cities. In 2015, Barcelona’s municipal administration stopped granting new licenses for short-term rental services and strictly controlled illegal renters by imposing huge fines on illegal hosts and Airbnb. In recent attempts, Barcelona’s local government has gained direct access to Airbnb’s database, which is very useful for identifying illegal flats and controlling the spread of Airbnb in the city’s central neighbourhoods. These initiatives have slowed down the expansion of Airbnb in Barcelona. Similarly, in 2016, the local government of Lisbon passed a law obliging Airbnb to require a local accommodation licence (Alojamento Local) from hosts who want to list their properties on the platform. In 2018, the national law on short-term rentals was amended to create buffer zones for Airbnb’s expansion. The historic city centre was included in these zones. However, Lisbon seems to be turning a deaf ear to the control of illegal expansion of Airbnb activity, to initiatives taken by other local governments, as the number of hosts continues to grow rapidly through 2019.

Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted Airbnb’s growth in both cities. Restrictions imposed on the movement of people by different governments have contributed to the collapse of Airbnb’s business. The number of listings has declined considerably. However, the biggest decline has been in the number of casual hosts. Most of the multi-hosts are waiting for pandemic control to resume their business. Potential rental income has declined in both cities, which may encourage people to remove their empty flats from Airbnb and pass them on to long-term tenants. However, the first initiatives by Lisbon’s local authorities to encourage this transition have not been well received by landlords. In the future, it will be interesting to see how Airbnb modifies its business model to be less disruptive to the housing market and how the local government controls the expansion of illegal short-term rentals in both cities.3