Introduction

This article puts forward and describes a new research method for examining society today, which we have called the visceral method. This method consists of a way of reflecting on individual subjectivity by showing previously selected photographs to participants in order to generate emotions and feelings about complex and hidden issues, so that we can identify a chain of content linked to underlying ideology (Van Dijk, 2006), without the restraint of the collective ethics that mask a discourse to make it socially acceptable.

This approach is particularly relevant in countries such as Spain, which has made considerable progress in gender equality policies (Astelarra, 2005), but where there is a significant gap between a superficial consensus concerning equality and the persistence of deep structures or gender patterns that reproduce male superiority (Hernández, 2010; Fassin and Galindo, 2008). In this context, it can be difficult to access these gender biases and stereotypes ( Aurrio et al., 2010; Jabbaz and Ingellis, 2019). The discourse on equality is being distorted: there are those who deny the existence of inequality but replicate it, or those who dilute it by including it with other forms of discrimination, violence, or problems. Ideologies organise and give rise to the social representations that groups share, and these form the basis of opinions. But ideologies are not simply made up of a list of beliefs: they are inherently heterogeneous and inconsistent, especially in times of newly emerging values, even if various writers, leaders, teachers, or preachers try to demonstrate their coherence (Van Dijk, 2006).

The methodological procedure is divided into individual and group phases in which the consistency of each participant’s answers and the reciprocal influence between them is observed. Identifying contradictions between the individual and group phases provides access to individually and socially hidden convictions and feelings.

The aim of this article is to show, step by step, what our visceral method consists of so that it can be reproduced in other cases and contexts. In order to explain clearly how we came to develop it, we include as an illustration the results obtained by applying the visceral method in a study we conducted with young men and women on the subject of gender-based violence.

This article aims to contribute to feminist research through specific procedures that allow us to explore prejudices and entrenched myths, while at the same time creating a process of collective consciousness-raising and transformation to make the social world more equitable (Blazquez, 2012; Delgado, 2012) and, thus, imagining possible scenarios of more egalitarian social relations and diverse relationship models (García and Montenegro, 2014). We, therefore, outline the visceral method, step by step, so that it can be reproduced for other cases and in other contexts. In order to explain its implementation more clearly, we present the results of applying the visceral method in a study carried out with young people of both sexes on the topic of gender-based violence.

Gender-based violence as a structural phenomenon

Gender-based violence has visible manifestations, but also a deep structure that has become naturalised and therefore difficult to recognise. At the same time, it interacts with the belief in white heterosexual male superiority ( Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005; Rodríguez-del-Pino, 2020). Consequently, it glorifies a model of femininity based on motherhood and emphasises a contract of submission to the patriarchal order (Roberts et al., 2019; Ballester, Orte, and Pozo, 2014). In this sense, gender-based violence is a structural and structuring phenomenon of social relations within a system of domination that is sustained through multiple overlapping layers in various temporal and geographical orders (Braidotti, 2002; 2011). Domination does not have a single matrix; indeed, it is intersectional because it includes various types of discrimination: sexual and gender discrimination, but also including ethnic, national, and social discrimination (Davis, 1981; Butler, 2007; Fraisse, 2016). All these categories contribute to the production of identities, and it is only through both individual and collective processes that new ways of thinking can be generated.

Del Valle has indicated that these deep structures are subconscious, but they are the origin of an important segment of the attitudes both within and towards different groups and social categories. “The problem lies in the lack of a methodological approach to identify this type of structure. Therefore, research has focused on identifying stereotypes that pertain to surface structures” (1997, p. 164). Espinar and Mateo (2007) point out that the term gender-based violence is rooted in dominant gender relations. Research into psychological, sexual, or economic violence may, however, be incomplete without taking into account the aspects that Johan Galtung (2004) indicates are linked to structural violence (situations of exploitation, discrimination, marginalisation, or domination) and cultural violence that arise from reasoning, attitudes, and ideas that justify, legitimise, and promote direct violence and structural violence. Kaufman (1999) also shows us another classification of significant forms of gender-based violence, which he calls the triad of violence, in which men are more violent towards other men, are violent towards women, and additionally internalise violence against themselves.

Structures of domination, as Bourdieu (2002) showed, are not overt and are based on symbolic violence that is exercised through an act of knowledge and practice of recognition that takes place below the level of consciousness and will, its manifestations being mandates and suggestions, as well as seductions, threats, reproaches, orders, or calls to order-it has hypnotic power.

It is, therefore, necessary to look at the complexity of who we are, from the local level, in order to construct a collective critical narrative (Braidotti, 2011).

We have only given a brief outline here of the hidden, cultural, and structural nature of gender-based violence, but enough to justify the importance of applying the visceral method to our example. However, the method we propose can be used to tackle any subject related to gender inequalities and discrimination of all kinds, as it allows us to establish a dialogical relationship between researchers and participants in order to tease out naturalised aspects derived from the mental categories of shared androcentric worldview.

Visual impact as an “emotional receiver”

The use of photographs as a methodological resource already has some history in anthropology (Hockings, 1975). In the exercise we present, the photographs were intentionally selected to reveal hidden feelings and attitudes among the individuals involved, and this is one of the main aspects of the method we present. We know that photographs have been used in different studies as a document or testimony, that is, as a research source because of the symbolic force they can convey, whether it is the representation of a battlefield (Wells, 2019) or photographs of weddings (Bourdieu, 1990). But in our case, photographs fulfil another function, as they are used to arouse an intimate emotion autonomically. For this reason, we have described our strategy for approaching these situations as the visceral method, since it evokes a gut reaction. Our source of information is the individual, and photography is an instrument that facilitates access to the information we want to collect.

We project a photograph to provoke feelings and interpretations in the participants, first individually and then in a group, to reflect and contrast, as in a kind of mirror, their beliefs and ways of feeling, thinking, and perceiving reality. And at the same time, we collect the discourses that the participants produce individually and in groups, in other words, when they have autonomy and when they are mediated and pressured by the peer group.

In brief, an image sends different messages, it is polysemic, but it also connects people with what they have experienced in common and reproduces their generational experiences (Rovetta, 2017; Maffesoli, 2003). The value of visual and audio-visual work in producing information has been recognised through the use of images in anthropology and social criticism. Thus, from very early on, the still image as a representation of fact and a complement to written information began to be understood as a cultural product that was subject to criteria, motivations, and dynamics that came from the external context in which the photographer moved. Bourdieu (1990) asserts that in some situations-for instance, weddings-the process of creating the photograph is so structured that it leaves little or no room for the photographer’s individual intentions.

The low impact that photography had initially in the academic world was, according to Prosser (2008), because of the undue priority academics have given to the written word over images. Gradually, however, photography began to be understood as carrying a message and, therefore, valued as a cultural product carrying intentionality (and widely used, for example, in ethnography). As Pink points out, this intentionality is conferred, “not only because the photographer manipulates the image he or she takes, but also because the photographed subjects manipulate and organise the way they want to be photographed, possibly doing so with personal or political ends in mind” (1996, p. 132).

We must bear in mind that a photograph is a document that represents an instant seen through the eyes or focus of the photographer, who establishes the frame and records certain facts or scenes but not others. Situations that are without interest according to the photographers’ subjective interpretation are excluded. Therefore, as Buxó (1999) describes, the challenge is to interpret how meaning is constructed-both the meaning of what is seen and what is not seen in the image. Once captured, however, the image no longer belongs to the photographer; it is his or her creation, but it will be re-signified, and therefore reconstructed, in as many ways as the gazes that fall on it.

In this way, the link between research and photography also becomes more complex, as it is not only a document that represents reality or constructed reality but also situated knowledge (Haraway, 1988). It is a reflexive and recursive situation in which multiple gazes converge to construct reality from a particular place. For this reason, photography is of great value in the social research process as it allows us to influence the participants involved in the study and interact with them in the field of knowledge, provoking reactions about the social and cultural aspects from their experiences and opinions (Ardèvol, 2006).

The implicit value of impinging on individuals’ consciousness is, as Dabenigno and Meo (2004) propose, because an image relates to imaginary or symbolic situations that represent something different for each person. The photograph helps to evoke memories and generates the possibility of returning constructed empirical evidence. These qualities help to integrate images progressively into research as a rich source with new possibilities for representation and interpretation. For Ana Lobo, using photographs in research “enables memories to be evoked” (2010, p. XX) and makes it possible to explore the participants’ structures of meaning and cultural frameworks.

In this way, the use of images allows us to research interviewees’ feelings (Lobo, 2010). Taking photographs as constructed and polysemous facts, we have designed the method to use photographs to trigger emotions, sensations, and memories, which are recorded immediately through simple questions. The use of images is a methodological resource to obtain narratives of irrational thoughts that respond to a stimulus beyond the intentionality of the photographer taking them (and also the research team selecting them).

The photographs are, therefore, chosen based on their symbolic power. The aim is for them to generate emotion in order to capture it. For this reason, it is necessary for the photograph to be suggestive, without suggesting any specific response. In short, photographs are linked to gut reaction, and the visceral method enables us to discern the feelings that they generate in those who observe them almost immediately and obtain a more truthful response than the meditated discourse that is collected through other media.

The focus of the visceral method

With the visceral method, we assume a feminist epistemological approach. The method allows us to analyse how similar situations can affect the lives of women and men differently, in a process of knowledge that is never finished and is therefore partial. The subjects driving the research also bring into play their personal characteristics, interests, and conditioning factors, which in turn influence the choice of the subject and the way in which the study is conducted (Haraway, 1988). We place the visceral method, therefore, within the field of feminist methodologies that consider the process of knowledge construction to be flexible and dynamic, and marked by its political and transformative character. In this context, subject-subject relationships are established between all the participants in the research and, as Castañeda (2008) demonstrates, the experiences lived through and recreated are an important source of knowledge because they emerge from the bodies themselves. Spontaneous situations such as viewing photographs uncover emotions that allow us to recognise significant contexts and reflect on them.

The methodological innovation that we put forward here is proposed with the aim of solving a problem that is ultimately political, namely, how to identify collectively, both as researchers and participants, mental categories based on gender stereotypes, which are difficult to apprehend because they are hidden, but which, if they remain unperceived, will limit our progress in the field of equality.

We have, therefore, combined different techniques such as questioning through surveys and focus groups, but with important variations that interrogate the neutrality of these types of methodological instruments. In the case of our surveys, far from ensuring that the questions were formulated unambiguously, as is standard in quantitative methods, we deliberately include suggestive images to arouse as wide a variety of emotions as possible. Our interest is not to observe empirical regularities (as is usual in conventional quantitative techniques); instead, the questionnaire is one more means, alongside the focus groups, to interpret the participants’ subjectivity in a granular way. Through this process, we also analyse the articulation that people make between emotions and reasons, not always coherently and, most interestingly, often fraught with a great deal of tension and confusion.

The method, step by step

Here we start on the nuts and bolts of the method, describing each phase, each process, and the decisions taken. If we were in the framework of a specific research project, it would be necessary to have designed the project and defined the objectives in order to then start with this stage, i. e., with the method itself.

It should be borne in mind that the visceral method aims to reflect subjective attitudes by showing selected photographs to the participants. The first step is thus the team’s selection of the photos to serve as elements to elicit and trigger emotions in the participants. It is, therefore, necessary for the people in the research team to define the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the images and their implications. As the process of evaluating images and applying criteria is not mechanical, it requires deliberation and an awareness that there will be biases involving their own subjectivity in the selection. One of the ways of controlling this possible bias is cross-checking meanings between the researchers themselves-in other words, bringing inter-subjectivity into play, so as to approach the topic of study by sharing perspectives. A research project is always a relatively arbitrary reading of the area under investigation. And in this reading, values play a fundamental role. This approach, as Pérez (2005) indicates, challenges one of the basic assumptions of the philosophy of science, objectivity understood as value neutrality, or science understood as impartial, autonomous, and neutral (Díaz and Dema, 2013). Here, however, we are not fighting against subjectivity but aim to make it part of our toolbox.

As a general rule, a key selection criterion should be to choose images with the greatest openness of content, which are not explicit, and give rise to multiple interpretations. As a result of this selection, possibilities for varied interpretations of the situations should be opened up.

As Donna Haraway (1988) asserts, the moral is simple: only a partial perspective promises an objective view. All Western cultural narratives of objectivity are allegories of the ideologies that govern the relations of what we call mind and body, distance, and responsibility. Feminist objectivity is about limited location and situated knowledge, not about transcendence and the division between a cognizing subject and an object to be known. Being a conditioned and conditioning part of the observation of reality is an essential element from a feminist perspective, as it allows us to be responsible for what we learn to see.

The second step is the selection of participants. In the case of the research we are using to illustrate this method, we used purposive sampling criteria (Glaser and Strauss, 2017; Barbour, 2018), adapted to group discussion technique (Llopis, 2004). What is important in this step is that the people invited to participate know that the visceral method involves an intense personal experience and that they themselves will be transformed by its implementation. This is similar to creating a theatre staging, as the research group forms a set or framework for action. The difference is that, in our case, it is not a play that is being performed, as the actors and actresses bring their own bodies, their own beliefs, and their own personalities into play when experiencing the visceral method. Therefore, being informed and willing to self-reflect is a fundamental ethical issue.

The third step is the work of producing information, through two related moments in which a group of approximately 10 people participate each time:

1st. individual phase: the participants are given an individual questionnaire so that they can indicate their immediate reaction to the visualisation of the images that are projected one after another successively on a screen and, after their reaction, explain or justify it.

2nd. group phase: the participants, who until then were looking at the screen individually, form a circle and the group discusses the same images that the facilitator projects, again one by one, and with the parsimony that the discussion requires. At this stage, anyone can say what they want, in order to determine what role each person assumes in the social scenario, as Erwin Goffman indicates in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956). As a clarification, it should be noted that the research team should not reveal the individual answers that each person gave in the first phase.

We shall now provide more details on each phase.

In the individual phase, each person is given a template with questions for each picture: What emotion does the following picture evoke in you? It is a self-administered questionnaire and, on their own, they mark an emotion with a cross: anger, sadness, amusement, or indifference. The fact that the alternatives are closed-ended facilitates an instant response. They are instructed to respond while the pictures are being projected and to choose one or more emotions. After indicating their choice(s), they can include a brief comment (two lines) explaining why they indicated that particular emotion (or emotions). Participants write their responses while the images are projected at a speed that is appropriate for them to record their reactions but fast enough to ensure spontaneous visceral responses or gut reactions. The images have a direct impact on emotions and we want to know the automatic responses and, then, capture any possible misalignments of the arguments concerning these sensations, as well as the nuances, tensions, and/or contradictions between these spontaneous emotions and the person’s values and ways of thinking. But the first thing is to scratch the surface and to include answers that we may not like or feel ashamed of for not being correct, but which are there, and which ultimately operate in our individual and social behaviours.

Once this first process has been completed, the second phase begins. In the meantime, part of the research team processes the questionnaires.

The second or group phase takes the form of a conventional discussion with the added feature that the elements discussed are the same images seen in the individual phase. In this situation leaders appear, as well as dominant narratives and some that appear subordinate but are, despite that, no less important. Goffman (1956) refers to the reciprocal influences that occur between those who share a situation. The role played by an individual adapts to the role played by the other individuals present who are observing her or him. When individuals present themselves to others, their actions will tend to embody and exemplify officially accepted values.

Discourse is not ideologically transparent and we cannot always infer individual ideological beliefs, which are dependent on how the communicative situation of all the participants is delimited, i. e., on the position each one occupies in the context (Van Dijk, 2006). To help the emergence of those unacknowledged aspects of who we are and how we have developed-to help deconstruct ourselves-we present the data gathered in the individual phase to the participants in an aggregated form, to be subjected to critique in the group phase; by contrasting the two, we can perceive the influences that bind us to the group with invisible threads. In the collective self-reflection, the participants will analyse the numerical data arising from the individual phase in a general way, without highlighting anyone’s particular choice.

All of this is essential in order to move on, perhaps, to a third, critical, and self-reflective stage, in which we produce a creative transformation in ourselves. This third stage is a possibility that goes beyond what is experienced in the visceral method, which may open up the path to that shift.

Feminist knowledge is an interactive process that brings out aspects of our existence, especially our own implication with power, that we had not noticed before. In Deleuzian language, it “de-territorializes” us: it estranges us from the family, the intimate, the known, and casts an external light upon it; in Foucault’s language, it is micro-politics, and it starts with the embodied self. Feminists, however, knew this well before either Foucault or Deleuze theorized it in their philosophy. [Braidotti, 2002, p. 13]

Furthermore, we understand that the process that begins with the visceral method produces cracks in the process of personal growth that last. We should bear in mind that the method we propose aims to realise aspects of knowledge about the subjects that are partially denied to their consciousness, but also, that its purpose is transformative and aims to be, in and of itself, a space for the recognition of prejudices and stereotypes and, as a result, for personal growth. In the research, therefore, we conducted a series of dialogues about the images, or to be more precise, about the subjective meanings we gave them in the framework of a reflective and transformative process that went from the individual to the group and vice versa.

An example of the visceral method in practice: young people’s attitudes to gender-based violence

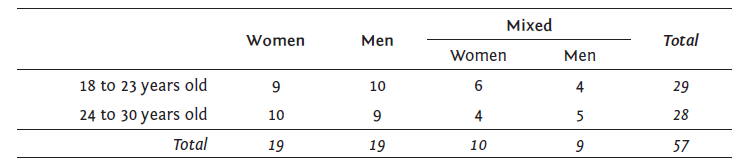

This section aims to provide an illustration of the method, in order to present it in a more complete way. To do this, we describe the research (Jabbaz, Rodríguez-del-Pino, and Gil, 2020), in which we applied the visceral method. Each image included was associated with one of the themes we wanted to address with the young participants: voyeurism, sexist humour, rape, prostitution, feminicide, micro-sexism, psychological and physical gender violence, sexist advertising, and gender stereotypes. Here, for reasons of space, we shall only address one of the topics covered: sexual violence. The criteria for inclusion in the sample were: sex and age (18 to 30 years old), and we scheduled six groups of 10 people each, as follows: women aged 18 to 23; women aged 24 to 30; men aged 18 to 23; men aged 24 to 30; mixed (women and men) aged 18 to 23, and mixed (women and men) aged 24 to 30. In total 29 women and 28 men participated. The participants were recruited from a range of different social groups based in the locality where it was carried out. Table 1.

Once we had defined the objectives of the project, we began to prepare the fieldwork, and the first step was selecting the photographs for use in the individual and group settings. The three members of the research team and an assistant were responsible for choosing the images. Each person chose three photographs found on the Internet for each theme, and then a discussion was generated around what each member of the team believed the image could contribute to the theme. But every image, because of its polysemy, shows the views of those looking at and interpreting it. In the case of those related to sexual violence, we discarded a photo in which there were clenched fists, another in which a woman was held tightly and, in general, those that presented violence in an explicit way. We finally chose a photograph of a man standing with his back to a woman sitting on a bed. Her head was bowed, held in both hands, while the man was buttoning his trousers. Both were young, as we believed that this would generate greater empathy in the participants, who were also young. Our aim was to depict sexual assault, but we wanted a visual narrative in which the participants could interpret the situation with greater degrees of freedom.

In the individual phase, the majority of the 29 women taking part reacted to the questionnaire by indicating anger: 13 women out of a younger group of 18-23-year-olds and 9 out of the 24-30-year-olds. The reactions of the 28 men were more varied: 9 men out of the younger range (18-23) indicated sadness, while those aged 24-30 were divided between anger (3), sadness (5), and both feelings simultaneously (6).

Analysing the discourses that emerge

The women’s comments relating to their anger included the following:

−“That shouldn’t happen.”

−“It’s outrageous, all relationships must be consensual.”

−“From the woman’s position, you can see that she is suffering and is afraid of what the man is going to do.”

The men gave the following comments along with their choices:

−“The man is abusing his girlfriend.”

−“Sad and painful because you can’t stop it.”

Significantly, 2 of the men aged 18-23 indicated that they were indifferent, and one made the following comment:

- “The woman is sexually dissatisfied.”

Despite this minority position, there was a consensus in condemning the situation presented in the photograph, from both women and men. However, the women reacted mostly with anger and the men with sadness.

The women’s anger denotes empathy with the young woman in the photo, as they later recounted in the group stage, whereas the men’s sadness is linked to not being able to prevent the situation, according to the evidence we received. In one case, however, a man did specifically blame the girl for her own situation.

In the group phase, social condemnation was not as strong. Among the 18-23-year-old males, they found it difficult to express how they felt about this image. The group began to outline their narrative with expressions such as the following:

- “The young man has forced her to do something she didn’t want to, and he’s gone too far, and she’s very upset.” (men, 18-23)

In verbalizing it, they are giving new meaning to the scene, indicating that “he’s gone too far” as if forcing her to do something she did not want to do was not in itself violence. Saying that she is upset reduces the man’s responsibility for the scene and lays the blame on the woman’s attitude. This formulation was questioned by other men within the group. Some of them questioned expressions that made the victim appear in a way that would make her responsible for the situation she was in:

−“She didn’t want to, but she doesn’t say anything at all.” (men, 18-23)

−“The girl didn’t know how to stop him.” (men, 18-23)

The testimonies echo the critique of feminist epistemology collected by Castañeda (2019) on the binary separation between feeling and thinking, body and mind, reason and emotion. The visceral method considers that there is a continuum in between feeling and thinking, not a strict separation, which is why we start from emotions as ways to access beliefs and, from there, what is naturalised as the only reality there is and, ultimately, therefore, as logical-rational thought. The image puts people in the situation; they are no longer asked about their beliefs directly but react as if they were really there. And this group of younger men mostly does so in a defensive way, without empathizing, or blaming the woman. In this way, spontaneous situations, such as viewing photographs, uncover emotions that allow us to recognise meaningful contexts and reflect on them.

When presented in this group phase with the aggregated data of the individual phase, the young men expressed how angry they felt about the possibility of empathizing with the assumed aggressor in such a situation. And they were also perturbed by the low score they had assigned to anger among themselves, which they related to their difficulties in empathizing with the victim. Based on this recognition, they then clearly defined the situation:

−“It’s a man who’s raped a woman.” (men, 18-23)

−“By force… because the woman’s suffering.” (men, 18-23)

At this point, there was a debate about strength and power relations within couples who begin to have a sexual relationship. Then other expressions appeared, such as the following:

- “I see her as helpless, she can’t do anything, and neither can I, it’s as if we were watching TV. Maybe we could have done something if we’d arrived earlier.” (men, 18-23).

And one young man goes even further:

− “You don’t see the violence in the image, but I can see the domination, because this is a clear situation and you see a person being dominated, not being able to stand up as an equal.” (men, 18-23)

Suddenly, what was being discussed among the men in this group took a turn and they asked themselves how they could establish more egalitarian relationships. There were phrases recognizing that women are suffering and there was a certain self-criticism as they stated that “we have to stop being just spectators of violence” (men, 18-23).

We can see how, in order to conceptualise gender-based violence, this group of young men went from looking at a photograph to discussions where they had to take a stance. They were addressing their difficulties in putting themselves in the place of women, as well as, to some extent, the entrenched values linked to the inequality that exists in society. In a way, they were reflecting according to the three constitutive dimensions of violence that Galtung points out in his triangle of violence:

The direct violence, physical and/or verbal, is visible as behaviour. But human action does not come out of nowhere; there are roots. Two roots are indicated: a culture of violence (heroic, patriotic, patriarchic, etc.), and a structure that itself is violent by being too repressive, exploitative or alienating; too tight or too loose for the comfort of people [Galtung, 2004, p. 6].

In the group of young men, it was also noted that this type of situation occurs in same-sex relationships and that sexual violence can be against women or against other men. Violence therefore appears as a form of interrelation and control (Rodríguez-del-Pino, 2020):

“There is also violence within the same sex, so I think it’s domination, which comes from a less educated mindset, making the other person feel helpless or causing them pain, and they shouldn’t feel that suffering.” (men, 18-23)

Clearly this drift in the debate was linked to situations that concern them, but this statement does not take into account that when the couple is heterosexual there is a structural gender asymmetry. And in terms of dominance factors, they were not able to see the differences between the two circumstances.

In contrast to the way the discussion developed among the younger men, in the group of older men (24-30 years old), the position towards violence was made clear from the beginning:

− “It’s a rape.” (men, 24-30)

− “It’s disgusting.” (men, 24-30)

− “… it’s lack of education, because of the system we live in, we men usually see ourselves a step above women, but that doesn’t give us the right to rape, or things like that.” (men, 24-30)

− “… And the feminist movement, it’s calling for what’s really needed. And we should be fighting for equality too, not just women.” (men, 24-30)

The group started talking about the role of the family in bringing children up and the degrees of individual freedom for couples:

− “It’s also influenced by upbringing and the culture you’re in, when it comes to acting, eh… I mean, mm… someone who has been brought up, I don’t know, in an environment with little violence, mm… might get out of control. Or they might manage to think things over, to relate, etcetera. Someone who… I don’t know, who has been brought up in a very violent environment…” (men, 24-30)

− “I’m a completely non-violent person… if you’re in one of those situations… so when I’m very angry, I either… I either shut up or I leave… and that’s it.” (men, 24-30)

While the younger group of men came up with secondary victimisation of women, this group was more reflective. They managed to understand the cultural origin of the violence but did not justify it.

Cultural violence plays a role in legitimizing structural violence, where power relations and all kinds of supremacy (including class, ethnicity, nationality) are located. In this case, the group’s dynamics led the members to verbalise how they belonged to one gender-male-and thus to reject self-exculpatory discourses. These young men assumed their social responsibility as a group and even put forward promoting education about equality as a cultural proposal. It must be said, however, that these cultural changes are conditioned by broader processes of social and political argument on which the feminist movement has had a decisive influence (Miguel, 2013; Carballido, 2010).

The group of women between 18 and 23 was very assertive about gender roles. The group style was very close to fourth-wave feminism, with more or less obvious criticism of their predecessors, with expressions such as the following: “I can like pink as much as I like yellow. I’m not a princess because I wear pink”. Regarding the photograph, the debate revolved around the meaning of gender-based violence:

- “Because of her gender, she’s more vulnerable than men. And male supremacy is because we live in a patriarchy.” (women, 18-23)

- “But there are also many vulnerable men, more even than you, and you can feel much more power of domination.” (women, 18-23)

- “Yes, but who’s afraid to walk the streets alone to get home?” (women, 18-23)

- “I can’t rape him.” (women, 18-23)

So, on sexual violence, among younger women, we find several juxtaposed discourses. In the individual phase, the vast majority of them reacted with anger, because all of them, in a very intimate way, know the vulnerability they experience and how interpersonal relationships can be a source of love and well-being or of insecurity and personal harm. Relationships are experienced and felt with a certain vulnerability. But when we moved on to group reflection, the discourses changed, and young women who are closer to feminist militancy speak of patriarchy, while others treat female and male vulnerability equally. We find, then, a gap between instant individual reaction and group reflection. As individuals, they felt vulnerable, but as a group, they were empowered and used language reinforced through feminist theory.

In the group of women aged 24 to 30, one of the most discussed topics was the insecurity involved in a casual encounter or a date with a man, a very important topic, as the discussion took place during the notorious trial of “La Manada”:1

- “Some people create a mental block [referring to the victim of “la Manada”]. I think that maybe it could happen to me … and I’d stay as still as a statue. Does that mean I’m enjoying it? Well, it might be my only way of getting out alive. And that’s not taken into account. I have many female friends who went out with their male friends or acquaintances and accompanied them and they weren’t raped, but then they say, ‘We were lucky not to have been raped’ and I find this outrageous …” (women, 24-30)

- “My God, how terrible [coughs], to say I was lucky because I wasn’t raped.” (women, 24-30)

This group of older women, in contrast to the younger group, showed a greater acceptance with regard to a certain sexual subordination to men’s desires. They expressed themselves in this way about non-consensual relationships with their partners:

- “I’ve heard from a friend, ‘Well, I had sex with my boyfriend and I didn’t really want to, but well… it’s like it’s a habit or… Well, otherwise we wouldn’t sleep and…’. In everyday situations of… I really don’t feel like it, but you end up making the effort because, look, because he’s your partner and you love him.” (women, 24-30)

- “I think that this happens because the woman feels like she has to satisfy the man. So, I don’t feel like it, but since I know that you do, then okay, yes. And it’s a bit like, yes, forcing, because of the sexist education we have.” (women, 24-30)

As we see, they considered the sexual submission of women within a relationship as something normalised, although they recognised that sometimes it can be a “forced” or non-consensual sexual relationship. When we talked about whether it was sexual violence, the positions were very varied. The group entered into a process of reflection and, finally, concluded that situations of this type are violent for them and that they have not learned to control them, which is part of their socialisation process.

As Gerda Lerner (1986) points out, cultural control of the symbol system is of central importance in consolidating male hegemony, which was achieved by denying women education for centuries and by men’s monopoly of definitions. Dismantling socialisation processes, therefore, requires processes of collectively constructing new conceptualisations, in order to escape the corset of categories emanating from a shared androcentric worldview which, as observed in this group, subordinates women’s sexual desire.

In the mixed group of younger men and women aged between 18 and 23, there was consensus on a phrase that naturalises gender stereotypes, indicating that “men place a lot of importance on sex, much more so than women”. This helps to maintain the belief that there are behaviours related to primitive and uncontrollable instincts in men and that men have special sexual needs (Ramos and Palomino, 2018). In fact, the sexual initiative is naturalised and blurred in the exercise of power (Yanagisako and Delaney, 2013):

- “I need sex, so I’m going to get it somehow…” [instrumentalizing women’s bodies] (man, mixed, 18-23).

They also reproduced the view of women as a controllable gender. This started a debate in which some people (women and men) saw sexual needs as necessary male biological urges, while another group, mainly women, saw these needs as social conditioning:

- “It’s not biological, because from an early age you’re taught the model of being a woman you have to follow.” (woman, mixed, 18-23)

- “We can look at history and see how what’s desirable has changed. Tastes change and the successful man is the one who gets that desirable type of woman.” (man, mixed, 18-23)

In the end, in this group situation with the space shared by both sexes, young women aged 18 to 23 were more critical than their male peers, although slightly less so than the non-mixed group of women of the same age.

In the mixed group of 24-30-year-olds, it was the men who limited their defence of masculinity, but showed little empathy with rape victims:

- “A lot of women go to the hospital, and when they tell her, ‘Report it’, and she doesn’t report, it’s her fault too…” [said with irony] (man, mixed, 24-30)

Some women also referred to the aftermath of psychological violence within a relationship:

- “I also think that when you are in that situation, you are not only physically abused, but psychologically…” (woman, mixed, 24-30)

- “You see an abuser and you see how he treats his partner… even if he doesn’t hit her and just yells at her, you know what’s going on.” (woman, mixed, 24-30)

In this group, some men tried to show that this kind of violent behaviour belonged to the past:

- “[the image shows] old values, […] it doesn’t happen now.” (man, mixed, 24-30)

Men showed little empathy for the victim and diluted the responsibility:

- “So, what’s happening to the woman? Think, man! They’re ruining his life!” (man, mixed, 24-30)

- “They’re both at fault, you know?” (man, mixed, 24-30)

- “The man because he wants to do it, but it’s also… the woman is to blame, for putting up with it and not reacting…” (man, mixed, 24-30)

- “If I were a woman and I was being beaten, I’d leave.” (man, mixed, 24-30)

Through the accounts, we see that gender-based violence is a phenomenon present in everyday social relations and, of course, it does not always show its most brutal face (direct violence), but appears masked, for example, by romantic love (García and Montenegro, 2014), tradition, religion, and many other forms. Therefore, engaging in a dialogical conversation with young people about gender-based violence involves a process of dismantling a whole series of elements that make up the culture of violence and that legitimise the situation of women’s structural subjection in a position of inferiority.

Results of the gender-based violence exercise

In the discourses analysed, it is clear that, individually, sexist behaviour is condemned. But after having identified the different reactions, it can be seen that on the whole women were angry and empathetic towards the situation, while men had a passive attitude and at no point did they put themselves in the place of the victim, even if they questioned the situation or were saddened by it (and the same was true when faced with other photographs).

We agree with Segato (2017) when she asserts the importance of analysing the intersubjective field in order to understand the different aspects in which sexual violence occurs. In this context, in the separate groups, we have been able to observe that, in the narratives that were freely produced there, the characteristics or aspects of female sexuality were a topic that was almost absent, uncommented on by any participant. And only in the group of younger women was there any alternative discourse contesting the dominant assumptions about male sexuality, in contrast with the group of young women aged 24 to 30, who recounted different forms of submission to sexual desire within the framework of being in a relationship. The discourse was less confident within the context of the mixed groups, where a superficial discourse on dominant sexuality was reproduced to a greater extent. Therefore, the rights of equality, freedom, expression of desires, and respect for otherness were concepts that were straining to emerge, but were diffused by social pressure. They do not fit in neatly with the more egalitarian sexual rights which most young people are nowadays involved in. There is a tension between a libertarian social discourse on sexual matters, which is even promoted by the media, and sexual practice subject to gender prejudices and stereotypes. Likewise, the issues of force, power, and control in couples’ relationships also arise. There are clear differences between men and women in the discourses. And in contrast to women, it is the younger men who find it most difficult to recognise that the present scenario is still very much shaped by sexist and patriarchal violence.

Bearing in mind that focus groups are artificial constructs, aimed specifically at capturing social discourses, we have been able to pick out some traces of the discourses that make up the substratum that continues to legitimise inequality and sexual violence: on the one hand, self-exculpatory discourses based on men’s nature and, on the other, the re-victimisation of women. And women, while their vulnerability is made visible, retain a sense of guilt and subordination. In this way, they recognise the conditioning factors since they are women, but find themselves in a vicious circle from which it is difficult to escape because, although they empower themselves, they know their own vulnerability.

The research team was careful not to reveal any evidence that could put the participants in an uncomfortable situation. Therefore, the group reflection on each of the 10 photographs shown was approached without revealing individual opinions (remembering that there we presented the aggregated results for a single photograph). The experience of participation is part of each person’s own process of growth and transformation, even if it is not shown publicly.

Conclusions

The visceral method offers tools for gaining knowledge about stereotypes and underlying ideology more directly through photographs. However, the aim of the method is not only to create a means of accessing scientific information but also a strategy for feminist awareness-raising and transformation. It proposes that the participants should be not only producers of knowledge for others (the researchers) but also involved in an experiential, collective, and self-reflecting way.

It is a dialogue within the groups of participants and is also directed outwards, because the research work tries to ensure that, from the contrast between individual and collective narratives, knowledge emerges about the deep structures of inequality, which are invisible and therefore more difficult to change.

The visceral method was conceived within the framework of research on gender equality and gender-based violence, precisely because of the symbolic nature of violence, which implies the unconscious consent even of those who are in a submissive situation.

Awareness-raising processes are essential to eradicate violence. However, in a time of transition, such as the current one in Spain, where the discourse on gender equality is gaining ground, and boys and girls are often taught to be more egalitarian at school and in media campaigns, the situation becomes even more complicated (Delgado, 2012; Aurrio, et al., 2010). They learn the discourse on equality but do not absorb it or commit to it, reproducing jealousy, a sense of possession, and even traditional forms of behaviour between the genders in relationships as a couple. Peer pressure continues to exert social control effects that limit freedom and equality. It is, therefore, important collectively to explore new paths and to reflect on the ways in which women and men interact. Within this framework, it would be significant to identify and dismantle the everyday elements that constitute hidden and subtle forms of violence and gender inequality.

Castañeda (2019) proposes three approaches among those at the forefront of producing knowledge, all of which are congruent with the visceral method in our opinion. In the first, which we used and have presented here in our example, the researcher is recognised as an active subject in the process, as are also the people with whom the research is carried out. This is the option usually associated with academic research. In the second approach, the research is more action-research and is the result of collaborative relationships between the researcher and some group, collective, or social organisation that establishes what is needed for knowledge and goals. The third perspective applies to researchers who belong to the same social group as those they are researching. This approach involves processes of dismantling current academic knowledge and validating their own knowledge, which brings with it non-canonical forms of research.

From the analysis carried out, we draw the conclusion that we need to generate more effective and more playful methods that will put individuals in situations that confront them with their own ambiguities and contradictions. All of this may make it possible to advance more effectively on the road to equality. The visceral method, acting at an instinctual level, will help those who use it to better digest the material that arises from the experience, so that they can raise awareness of stereotypes and, in this way, develop ways of thinking, feeling, and being more consistent, coherent, and free.