Introduction

Political parties and interest groups represent distinct channels of representation, yet they also cooperate in the electoral, institutional and societal arenas.1 This shared dependence on mutual resources is precisely what might provide the means for interest group-party linkages. Indeed, the interaction between groups and parties not only shapes the content of public policies but also the nature of interest representation (Schattschneider, 1948; Easton, 1957).

The linkages between parties and interest groups have been conceptualized in distinct ways, leading also to different operationalizations. From party membership or the group point of view, party-group interactions have focused mainly on organizational or behavioral dimensions. On the one hand, the institutional perspective has emphasized the formal links established by parties by looking at their statutes and their collateral organizations (Poguntke, 2006; Allern and Verge, 2017). On the other, a growing number of works are examining the intensity and types of contact between political parties and interest groups (e. g. Rasmussen and Lindeboom, 2013; Otjes and Rasmussen, 2017), a strategy that has become increasingly common due to the rising popularity of interest group surveys (see Marchetti, 2015; Pritoni and Vicentini, 2020).

Yet, recent studies have noted that the collaboration between these two types of collective actors has become less institutionalized and structured than in the past (Allern and Bale, 2012b; Rasmussen and Lindeboom, 2013). Most scholarship argues that parties are no longer interested in establishing close ideological and organizational ties to interest groups, as this type of linkage can be a constraint in a context of electoral volatility and declining citizen involvement in traditional associations. However, trade unions and businesses alike still exchange political and technical information with political parties as a means of maximizing their chances to impose their views and their interests on specific policy outputs.

To what extent are party officials members of organized interests? How do different parties establish personnel linkages to interest groups? And how has this leadership overlap evolved over the last decades? This study addresses these issues by relying on an original dataset that draws on the Portuguese case. We argue that personal linkages between parties and interest groups can shed more light on this connection for several reasons. First, this research focus may reveal both how parties and group discipline each other and how partisan and group identities become interconnected (Heaney, 2010). Second, systematic investigations of the responsibilities within parties and groups help illuminate party-group networks and they may provide evidence of the subtle but profound connections between parties and groups. Last but not least, the analysis of party-group connections at the leadership level may also lead to new insights into recruitment patterns and the evolution of career paths over time.

This study aims to contribute to the literature on the subject on both theoretical and empirical grounds. On one side, we adopt an underexplored operationalization of party-group linkage by focusing on leadership overlap in multiple layers of party organization, namely in the extra-parliamentary party and also the party in public office.2 On the other, we analyze original data based on the composition of the main party and group decision-making bodies in Portugal, which is clearly a neglected case in terms of the study of party-group interactions. The fact that it presents a significant variation of political actors, from both the organizational and ideological point of view (see below), and that it includes economic associations at the peak level with distinct ideological profiles and political alignments (see Magone, 2014; Lisi and Loureiro, 2019) make it an interesting case study that can provide useful insights for other European countries and party-based democracies.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: the next section reviews theoretical arguments regarding party-group connections at the elite level; we then contextualize the Portuguese case and we derive a set of four hypotheses on leadership interaction in three distinct arenas; the fourth section presents our research design, data and the methods used to analyze these linkages; section five empirically examines leadership overlap in Portugal before and after the euro crisis; the conclusion summarizes the main findings and the implications of party-group relations for the overall system of interest intermediation.

The complex relationship between parties and interest groups: personnel linkages and leadership overlap

There is broad consensus in the literature that there has been a ‘retrenchment’ of parties from civil society over the last decades. The increasing distance between political parties and interest organizations - together with decreasing levels of party membership and a more heterogeneous support base - has been interpreted as a sign of the so called ‘party crisis,’ specifically with regard to the loss of their intermediation function (Dalton and Wattenberg, 2000; van Biezen, Mair and Poguntke, 2012). Indeed, data collected within the framework of the Political Party Data Base (PPDB) show that only 10 out of 122 parties (8.4 percent) have formal links to trade unions, and connections with other groups are even more uncommon (Allern and Verge, 2017).3 Moreover, recent trends in party development suggest significant growth in the parties’ detachment from civil society, while institutional resources have become increasingly important (Katz and Mair, 1995; 2018; Ignazi, 2017).

This shift of party-group interactions in the institutional arena has led to a focus on how these links develop within the Parliament. Legislatures provide interest groups with channels to access decision-making institutions and influence policy outputs. More importantly, parliaments represent a key arena to develop party-group interactions. In general, interest groups have three main access points to parliament: committees, parliamentary groups (as a whole) and individual MPs. The access points may be reached by using two distinct types of instruments, namely formal or informal links (see Lisi and Muñoz, 2019). Formal channels are regulated by parliamentary rules and are conducted mainly through committees; specifically, interest groups participate in hearings to discuss bills or public policy implementation. Conversely, informal channels may develop through individual ties based on the deputies’ work representing their constituencies (or specific issues), or due to the MPs’ belonging to a specific parliamentary group, thus intermediating the interaction between parties and legislatures.

Although informal contacts between MPs and group representatives are an important strategy of interest organizations, the lack of available data precludes a systematic investigation of this phenomenon, especially from a comparative perspective. One way of pursuing direct contacts may be through the practice of ‘revolving door’ or more formal recruitment channels.4 As has already been noted (e. g. Musella, 2015), political careers have changed significantly in recent years. While becoming president or prime minister was traditionally seen as an achievement resulting from a long journey within the institutional arena, top-level politicians are increasingly likely to use their political experience to start a new career in a broad and diverse range of business activities. A comparative study on the career path of democratic leaders shows that the average age of outgoing presidents or prime ministers has declined over time, thus opening up new opportunities for the beginning of professional activities in the business sector (Musella, 2015). However, the focus does not include the interaction between parties and interest groups, nor does it offer a longitudinal view of the evolution of this relationship.

This study focuses on the personnel linkages between parties and interest groups, understood as the overlap of leadership positions in the two types of organization. Such ties are generally considered an indicator of the closeness of the two actors of intermediation (e. g. Grossman and Dominguez, 2009; Heaney, 2010; Celis, Schouteden and Wauters, 2016). Heaney et al. (2012) considered co-membership as the degree of overlap between people that belong to a party and members of a political organization. We take a similar approach, considering leadership overlap as the proportion of party leaders that simultaneously hold top positions in the main interest organizations’ bodies (see next section for more details on operationalization).5

Parties may recruit from interest groups for a variety of reasons. One aspect is they may look for political support, thus enhancing their mobilization capacity, which may ultimately improve their electoral performance. Parties may also strengthen individual ties to specific interest groups with the aim of boosting their legitimacy. Accordingly, in light of a growing distance between parties and civil society (e. g. van Biezen and Poguntke, 2014; Ignazi, 2017), party organizations may decide to enhance their representative potential by diversifying or increasing the proportion of civil society representatives within the main party bodies. Another aspect is that interest groups may find it useful to have leaders with a partisan profile in order to become more influential in policymaking. In addition, there may also be internal benefits, as political experience may boost the effectiveness of the group organization, fundraising activities or the training of professional cadres. Finally, the recruitment of a previous party leader may also augment the visibility of specific interest groups, in terms of media exposure and social legitimacy.

Interest group politics has developed a number of ‘exchange theories’ that account for party-group collaboration. As the linkage between parties and interest groups has generally shifted toward informal ties, leadership overlap emerges as a key dimension to explore. Leadership ties allow both types of organizations to better adapt to the environment and to ensure more flexibility to external uncertainties. In addition, leadership links may also foster an exchange between politicians and groups in terms of information and trust. As several studies have already stressed (Kirkland, 2013; Fouirnaies and Hall, 2018), these are two vital commodities of politics that may influence the strategy of actors, the mobilization of specific resources and also the content of policies.

Based on the American case, Heaney (2010) has drawn attention to two main mechanisms that may foster party-group relations through leadership overlap. The first is based on the establishment of party-group networks, which aim to unify their action and maximize their potential for policy influence. This usually implies a brokerage relationship, especially when parties and groups do not have enough time or resources to develop permanent structures. The function of brokerage may be conducive to a variety of goals, such as the creation of new alliances, the elaboration and implementation of reforms or the competition between parties and groups to achieve shared goals.

This situation may also lead to the second mechanism highlighted by Heaney (2010), namely the attempt to develop ‘discipline.’ Overall, discipline can be interpreted as the ability to influence the kind of agents that participate in politics (Foucault, 1978). Thus, another possibility of leadership overlap is to allow the party/interest group to exert a reciprocal influence. Both outside and inside the institutional arena, discipline may be used to gain control by putting agents (parties or groups’ representatives) into place that act in a certain way. This situation can be associated with the logic of ‘control’ highlighted by the cartel party literature, according to which the recruitment or appointment of individuals is instrumental to the monitorization of policy outcomes and results (see Kopecky, Mair and Spirova, 2012).

Despite the relevance of these exchanges, party-group relations at the leadership level have largely been ignored by the scholarship. Any reference to the subject has been investigated quite randomly and there is a general lack of theory. Moreover, most of the works have tended to focus on Anglo-Saxon countries or advanced democracies. This article aims to go some way toward redressing this balance, analyzing a dataset of party and interest group leaders over the twenty-first century.

Exchange theories are not the only explanations that account for party-group interaction in the parliamentary arena. Collective or ideological motivations are equally important. On the one hand, over the twentieth century, parties and groups were developing along traditional cleavages, thus establishing (more or less) strong relations, especially when sharing the same ideology (Allern and Bale, 2012a). On the other hand, studies based on descriptive representation theories highlight the importance of identity as a source that determines the desirable profile for MPs. In other words, representatives are expected to share the social identity of a specific group, and this is a key linkage between politics and society (Phillips, 1995; Mansbridge, 1999). A comparative study based on established European democracies found that the extent to which MPs create contacts with trade unions and business associations is based mainly on their party affiliation (Celis, Schouteden and Wauters, 2016). Therefore, social democratic MPs are more likely to exhibit ties with trade unions, while conservative deputies show stronger ties with business organizations.

The fact that distinct party families establish connections with specific interest groups is also confirmed in case studies. In the Swiss case, for example, partisan links between MPs and business associations become considerably stronger when we move from the left to the right of the political spectrum (Gava et al., 2016). In the Portuguese case, we also find a closer link between leftist parties and trade unions, whereas right-wing parties are more likely to display stronger linkages with business organizations (Lisi, 2018). Considering the arguments above, our first hypothesis regards leadership overlap between the members of the party in the central office and interest groups, and it claims that left-wing parties are more likely to display stronger networks than right-wing parties (H1: party central office hypothesis).

In addition to the ideological/partisan distinctions, we also need to account for the variety in the studied groups and their legacy in terms of organizational linkages. When it comes to the asymmetries between economic groups, empirical research has shown that trade unions and left-wing parties are still trying to maintain some sort of linkages. Despite the overall trend of de-linking or weakening party-trade union ties, in most European countries both types of actors still consider it valuable to establish formal or informal connections (Allern and Bale, 2017). It has also been argued that business associations are more prone to directly contact government officials given their ‘insider’ nature, while trade unions are more likely to rely on their political allies (Binderkrantz, 2008). This is true, especially in the context of the high relevance of social concertation and when there are predictable patterns of government that exclude the participation of unions’ supporters (Royo, 2001). As a consequence, we expect to find more dense networks in trade unions than in employers’ associations, which are generally more competitive and more fragmented than labor organizations (Lanzalaco, 2008). Given the asymmetries we found in the party-group organizational linkages together with the strength of distinct interest groups, our second hypothesis is that trade unions are more prone to develop leadership networks than employers’ associations (H2: interest group hypothesis).

Empirical studies based on party-group surveys indicate that central party organizations are less likely to have leadership contact than parliamentary party groups (Allern et al., 2021). This finding is not surprising, since parliamentary representatives are directly responsible for drafting and deciding on legislative proposals. Given the importance of expertise and knowledge of specific policies, it is expected that parties would prioritize the recruitment of group representatives as candidates or MPs. Therefore, our third hypothesis argues that personnel overlap is higher in the party in public office than in the party central organization (H3a). As aforementioned, the same pattern that associates distinct party families to specific organizations should be observed also for the party in public office. Consequently, we also posit that trade unions are closer to left-wing MPs (or candidates), whereas right-wing parties’ MPs (PSD or CDS-PP) tend to establish more ties with employers’ organizations (H3b).

To what extent has the economic turmoil since the onset of the global crisis affected party-group relations? First, the policy shifts and the neoliberal convergence of mainstream parties led to a decline in partisanship, strengthening the process of dealignment and the erosion of public support for established actors. Second, there has been a growing distrust toward both domestic and European institutions (Muro and Vidal, 2017). Third, Portugal experienced a deep process of mobilization during the Troika (European Bank, International Monetary Fund and European Commission) intervention, which reached a peak in the 2012-2013 demonstrations, characterized by new types of collective action and innovative forms of interaction between parties, movements and interest groups (Freire, Viegas and Lisi, 2012).

What does this mean for leadership interactions between parties and interest groups? Given this contextual background, we contend that the crisis represented a critical juncture that may make different types of organizations revise their mobilization strategy and the resources used to influence policymaking. The growing lack of responsiveness of governments hardly hit by the global economic and financial crisis is expected to influence the type and intensity of linkages established between political parties and organized interests (see Tsakatika and Lisi, 2013). The increasing disconnection of political parties from civil society may lead political leaders to change patterns of recruitment, in particular by bringing new political personnel into the democratic political systems (e. g. Coller, Cordero and Jaime-Castillo, 2018; Freire et al., 2020). Thus, our first hypothesis claims that since the outbreak of the Great Recession, the relationship between parties and groups has strengthened (H4a). In particular, we also hypothesize that trade unions will display a greater increase in their centrality on party networks over time compared to business’ organizations (H4b).

Having examined the relevant scholarship on party-group ties and the main hypotheses, we now present the Portuguese context. After this, we discuss the new data we have collected to make the inquiry possible.

The portuguese case

This work focuses on the main Portuguese parties that have been able to achieve parliamentary representation over the last decades. This means that we consider the two moderate and centrist parties - the Socialist Party (PS, Partido Socialista) and the center-right Social Democratic Party (PSD, Partido Social Democrata) -, the right-wing Democratic Social Center/Popular Party (CDS/PP, Partido do Centro Democrático e Social/Partido Popular), as well as two radical left forces, i. e., the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP, Partido Comunista Português) and the Left Bloc (BE, Bloco de Esquerda).6

As for the sphere of interest groups, our analysis considers the main Portuguese trade unions and employer confederations. The General Confederation of Portuguese Workers (CGTP, Confederação Geral dos Trabalhadores Portugueses) is the communist-leaning trade union confederation that quickly surfaced as the dominant peak-level organization in the aftermath of the democratic revolution, but soon faced competition from the socialist-leaning General Union of Workers (UGT, União Geral dos Trabalhadores). On the employer side, the Portuguese Business Confederation (CIP, Confederação Empresarial de Portugal) is the main actor and mostly represents the manufacturing sector, although its domain has also expanded to the services over the years. The Portuguese Commerce and Services Confederation (CCP, Confederação do Comércio e Serviços de Portugal) and the Portuguese Farmers’ Confederation (CAP, Confederação dos Agricultores de Portugal) are the other main representatives of employers.

Other than some exploratory studies conducted in the early years of the democratic period (Lucena and Gaspar, 1991; Schmitter, 1992), party-group relations have not been systematically investigated and there is a general lack of knowledge on the topic. Most studies have addressed this issue from the parties’ standpoint, examining mainly the organizational dimension, i. e., the formal links established between parties qua organizations (looking at party statutes) and the main interest groups (Lisi, 2013; Razzuoli and Raimundo, 2019). Some works have focused on the parliamentary arena, by considering MPs’ profile (e. g. Fonseca de Almeida, 2015). Finally, a number of studies have tried to analyze informal links and personal connections between parties and private entities, gathering empirical evidence on the importance of these interactions in terms of the decision-making process and policy outputs (e. g. Coroado, 2017). These studies are associated with the general theme of corruption, providing scattered evidence on the mutual benefit that these interactions may entail for both sides. These links concern mostly the two main governing parties (PS and PSD), but they do not systematically examine the intensity of this phenomenon, nor the variation across parties and over time.

Previous works conducted for Southern European countries indicate that the variety in the patterns of party-group relationships depends not only on ideological affinities but also on organizational models (Morlino, 1998; Tsakatika and Lisi, 2013). Empirical findings for the Portuguese case confirm that there is a significant variation in the type and strength of linkages between parties and the main interest groups. The PCP has historically displayed the strongest linkage with the CGTP, although the interaction has weakened somewhat over the last decades. The BE shows weaker ties, but it has tried to strengthen this collaboration, especially during the Great Recession (Razzuoli and Raimundo, 2019). The PS - and, to a lesser extent, the PSD - has some loose ties with trade unions, mostly with the UGT. Finally, right-wing parties (PSD and CDS-PP) show no organizational links to the main interest groups, but they both have collateral organizations with the aim to articulate and structure the participation of union members in party activities.7 Despite the fact that some of their programmatic stances are in line with business organizations’ interests, social dialogue during the Troika period harmed the collaboration between right-wing parties and social partners.

The second strand of research has focused on the link between MPs and organized interests. Data drawn from several surveys of parliamentary candidates conducted in the 2002 and 2009 elections confirm that communists are more strongly anchored to the labor movement, whereas the BE has more differentiated links to civic organizations. When we look at trade union membership, we find very high integration among communist candidates (60 percent of communist candidates are also members of a trade union); the socialists show the weakest anchorage, with the BE occupying an intermediate position (between 37 and 43 percent). This finding is also confirmed by recent surveys to MPs, which found that communist sympathizers are significantly more likely to participate in trade unions than BE militants (Viegas and Santos, 2009, pp. 136-137; Lisi, 2018). On the right side of the political spectrum, it is worth mentioning the link between CDS-PP and religious associations, as well as organizations linked to the ‘third sector’. Finally, the two main governing parties (PS and PSD) display links typical of the catch-all parties, i. e., more heterogeneous and pluralistic ties with civic associations, mostly based on professional associations, solidarity organizations and, to a lesser extent, trade unions (e. g. Lisi, 2014; 2018).

Anecdotal evidence shows that there are cases of the revolving door in Portugal (Costa et al., 2010; Pereira, 2014; Coroado, 2017). While examples of high-profile politicians and civil servants in Portugal leaving the public sector for lucrative private employment opportunities are recurrently in the media, party leaders may also take an active position in the main groups’ governing bodies. The clearest case is the PCP, which has dominated the leadership composition of the main trade union (CGTP).8 However, there is little systematic evidence about the ties left-wing parties have with trade unions. Similarly, we still lack empirical evidence of the relationship between right-wing parties and employers’ associations.

Data and methods

In order to examine party-group relations at the leadership level, we focus on the main executive bodies of both parties and interest groups. For the former, we follow the distinction elaborated by Katz and Mair (1993) between the party in public office, the party central office and the party on the ground. The first dimension is associated with the party face in parliament or government, while the second is based on the national leadership of the party organization (Katz and Mair, 1993, p. 594). As a number of authors have shown (van Biezen, 2003; Jalali, 2007; Lisi, 2011), these are the two most important party faces because the extra-parliamentary party enjoys remarkable powers, although the party in public office displays an important functional autonomy. Indeed, according to van Biezen’s study (2003, p. 213), “party organizations appear to have become increasingly controlled from a small center of power located at the interstices of the extra-parliamentary party and the party in public office.” As far as interest groups are concerned, the choice to focus on the main executive bodies is quite clear, especially given the hierarchical configuration of peak confederations (see below).

Portugal is a suitable case for the study of party-group linkages at the leadership level for two main reasons. First, there has been remarkable stability in terms of political recruitment over the period under study (see Lisi, 2018). The process of candidate selection is relatively centralized and there is not a huge variation in terms of inclusiveness among parties. Stability also characterizes the evolution of party organizations, with no significant changes with regard to the composition and powers of the main party bodies.9 Second, the institutional and political stability that has characterized the Portuguese political landscape over the last decades means there have been no relevant alterations in the incentives and opportunities for party-group interactions associated with the political environment. The existence of a tripartite body for social concertation that includes all the interest groups considered in this study further supports the suitability of this context for the analysis of leadership overlap.

We collected data on the composition of the interest groups’ national executive bodies, the political parties’ candidates for national elections, their elected MPs and the composition of parties’ national executive and deliberative bodies.10 The period considered in this study extends from 2002 to 2015. While it was not possible to collect complete data for the period before 2002, this time span is large enough to detect systematic trends. It also allows us to distinguish between two periods, namely before (2002-2009) and after the crisis (2009-2015).

The above lists were automatically processed and analyzed in order to produce a complete list of full names of party and interest group officeholders. All the cases where first and last names matched a mandate in both a party and an interest group were manually verified to ascertain the actual existence of an overlap. In the end, the complete list comprised about 4,600 individuals. Our unit of analysis is the dyad party-group leadership, i. e., the overlap at the top position in both organizations. This is how we operationalize our key dependent variable (leadership overlap).

After this initial coding, we created an edge, or connection list that tied each officeholder to every other official that shared membership in a party or interest group body during the same mandate. We also analyzed the internal network of each party using the igraph package for R11 to measure each members’ centrality. For this purpose, we weighted different connections differently. Namely, we scored each party body from 1, for candidates’ list, to 5, for MPs and party executive officers. The rationale behind this operationalization is that the role of elected representatives and members of the main party bodies are clearly more important than candidates.

To measure each member’s centrality, we calculated individual eigenvector centrality scores. This choice is justified since we wanted to measure who each person is tied to, rather than how many connections each member has. Due to the limitation of formal ties, the actual number of connections for each member is pre-determined by each specific institutional setting. We, therefore, used a measure that highlights the relationship to high-ranking individuals while de-emphasizing lower-ranking individuals (Bonacich, 2007).

Results

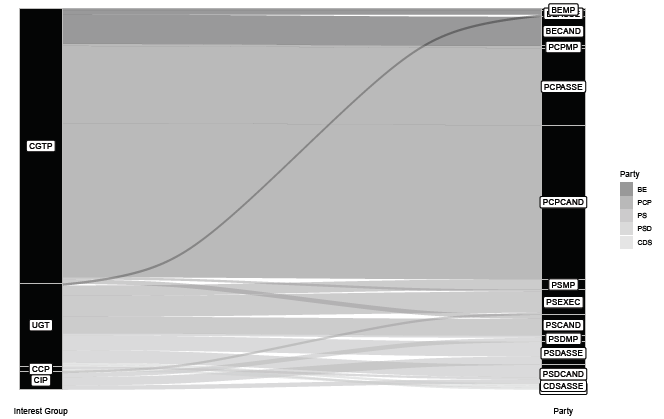

Figure 1 presents an alluvial plot that links interest groups’ officeholders and the party leadership (in public or central office). While most interest group officeholders are not members of party leadership, about 183 of them were also party officeholders. It should be noted that the unit in Figure 1 is the individual and not mandates. In fact, many of the individuals, who are office holders of either interest groups or parties serve more than one mandate, disproportionally more so than non-partisans in some cases. Most of these ties are related to the PCP and its links with the main trade union confederation (CGTP). PS and PSD display a similar proportion of leadership overlap, mostly connected with the UGT. CDS-PP is the party that displays the lowest level of leadership overlap. This comes as no surprise given the ‘minimalist approach’ adopted by this party in terms of linkage to interest groups (Razzuoli and Raimundo, 2019, p. 636), as well as its peripheral position within the party system.

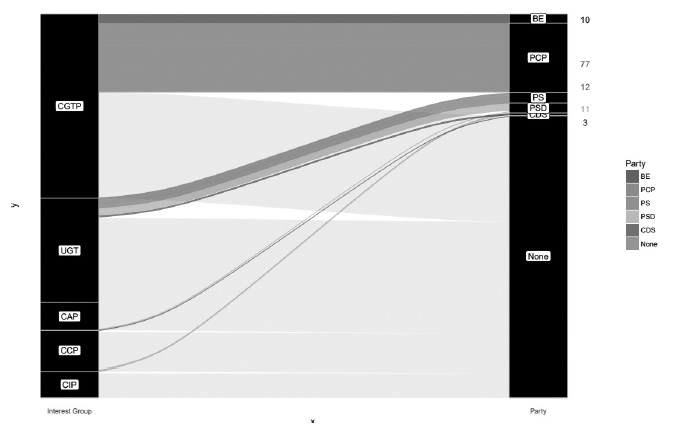

Figure 2 presents an alluvial plot that links interest group office holders who are party members and their role inside the party. This figure clearly shows that there are more connections between trade unions and political parties, notably left-wing parties. There are only a few connections between business associations and political parties, which - excluding just one case - are all right-wing parties (H2 confirmed). It is also worth noting that these ties are equally distributed between the party in public office and the extra-parliamentary party. However, our data suggest that the recruitment of labor activists in left-wing parties (i. e. belonging to trade union organizations) tends to fill positions in public office, rather than in the party bodies. Figure 2 also illustrates the clear division in Portuguese trade unions. While CGTP has representatives in all three left-wing parties (BE, PCP and to a lesser extent PS), the UGT representatives are all in the center parties (PS and PSD), except for one in BE. It also shows the close connection between CGTP and PCP. More than 110 CGTP leaders were also PCP office holders during this period. Another surprising fact is the absence of connections between a formal position in any interest group and being an office holder in CDS-PP. In fact, for the whole 2002-2015 period analyzed, only three CDS-PP office holders belonged to any interest organization. Interestingly, one of them was a trade union representative.12

Figure 1 Party-group leadership overlap (2002-2015). Note: The total number of Interest group leaders in each party membership is displayed on the right. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 2 Interest group membership and party role (2002-2015). Source: Author’s elaboration. Note: On the left side, the term after party abbreviations refers to candidates (CAND), deputies (MP), members of the executive body (EXE) and members of the deliberative body (ASSE).

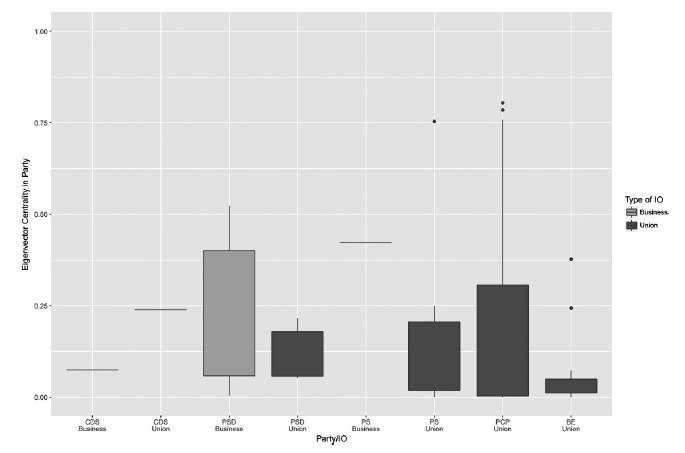

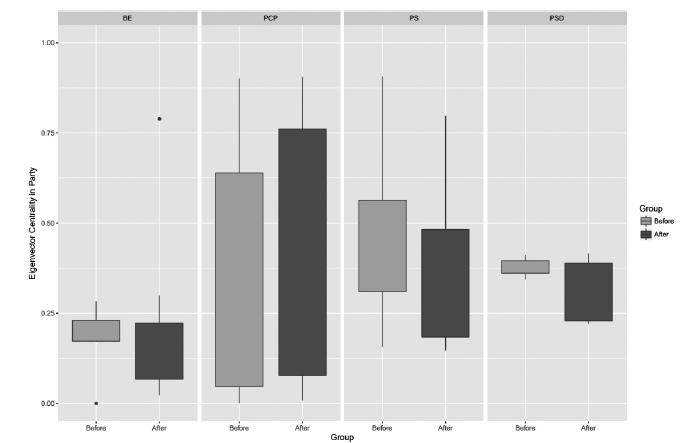

Figure 3 presents a boxplot of the eigenvector centrality of interest group members inside each party, split between union and business representatives. Note that the centrality measure we used is highly and positively skewed, which implies that only a few cases have higher centrality values. Hence our key characteristic of interest is the span in values when comparing between parties.

Figure 3 Boxplot of the centrality of interest group members inside each party (2002-2015). Source: Author’s elaboration.

When comparing centrality measures, it is clear that union representatives occupy much more central party positions in left-wing parties. This is especially the case of PCP. Not only are there more trade union members in its main office, but they also have more central roles in the party. However, BE represents an interesting exception to this rule. Despite being a radical left party and having union leaders as formal members in party bodies, their centrality inside the party is surprisingly low. Indeed, this indicator shows lower levels than those displayed by UGT representatives inside of PS. This result might be explained by the peculiar organizational characteristics of this left-libertarian party, which adopted more open patterns of recruitment and whose internal functioning is oriented (at least in principle) toward the enactment of internal democracy and deliberation.

Figure 3 also suggests an interesting aspect with regard to PSD. Although it has more union representatives in its party offices, business representatives are more central in the party network. This example demonstrates the importance of not only counting the number of interest organization representatives inside each party but also their relative importance in each party’s network. The situation in PS could be said to be similar, but there was only one business organization office holder in the party’s formal network during the whole period.13

Combining the information gleaned from all three figures, we can conclude that hypotheses 1 to 3 are corroborated by the data. Left-wing parties seem to be more connected to interest groups when compared with right-wing parties. This pattern seems to be correlated with the position on the left-right political scale. The more right-leaning the party, the fewer the connections established with labor organizations.

Labor interest groups are more represented inside party offices when compared with business organizations. More trade union members belong to the main party bodies, and they are also represented in more parties. While their presence in radical left parties is clear, they are also present in center-left and center-right parties. However, it should be noted that the quantity of labor representatives is not always matched by their centrality, which seems to depend partially on the party’s left-right position. The more left-leaning the party, the greater the centrality of the union representative. Our results suggest there is a clear affinity between trade unions and left-wing party organizations. The importance of trade union representatives rises both numerically and in terms of centrality as parties become more left-leaning. Nonetheless, BE does not comply with this norm, a finding that is rather difficult to explain. Although this radical left force has competed strongly with PCP in order to prioritize labor issues, BE has had great difficulty penetrating the main trade union (see Lisi, 2013). Furthermore, the ‘movement’ nature of BE privileged stronger ties with civic associations, identity groups and public interest organizations (e. g. human rights, environment, etc.).

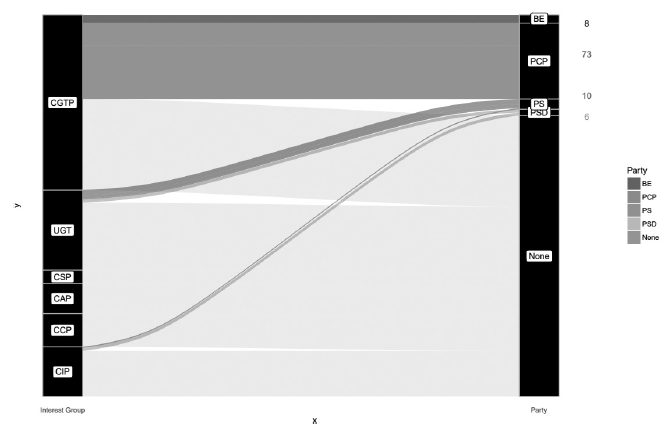

Figure 4 Interest group leadership and party membership before the crisis (2002-2009). Note: The total number of Interest group leaders in each party membership is displayed on the right. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Figure 5 Interest group leadership and party membership after the crisis (2011-2015). Note: The total number of Interest group leaders in each party membership is displayed on the right. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Turning to our last hypothesis, we split our data into two different moments to test the effect of the crisis on the connections between interest groups and parties. The first spans from the 2002 parliamentary elections to the legislative elections in 2009, which corresponds to the pre-crisis period, and the second from the latter elections to the 2015 parliamentary elections, which corresponds to the crisis period.

Figures 4 and 5 show the connections between interest groups and parties before and during the crisis, respectively. We can conclude that, when we look solely at the number of interest group representatives, there is a small decrease overall. While 113 interest groups leaders were also party officeholders before the crisis, this declined to 97 after the crisis.

When looking at within-party differences, there is a clear (albeit weak) trend for labor representatives. The number of union leaders decreases after the crisis for PSD, PS, PCP and BE. Therefore, our data do not seem to corroborate hypothesis 4a. When looking at all the parties, even the number of union representatives goes down during the crisis.

Figure 6 presents the boxplot of the eigenvector centrality of union leaders inside each party before and after the crisis. We excluded CDS-PP from this figure since it had only one labor representative in its office during the whole period. This figure shows two divergent trends. In the case of PSD and PS, the few union members that were still represented inside the party offices after the crisis played a less central role than they had before the crisis. From this viewpoint, it seems that the crisis had an effect not only on the number but also on the role of union leaders inside the party. It is difficult, of course, to say whether this finding is due to the impact of austerity measures - i. e. the opposition from both inside and outside the party to neoliberal policies implemented in that period - , or whether it is simply the result of a change in party strategy.

A different trend occurs inside PCP and BE. For both parties, there was a slight increase in the union leaders’ institutional role. Nevertheless, given the small number of union leaders in BE, this increase in centrality is due to a clear outlier.14 Contrary to hypothesis 4a, it seems that hypothesis 4b is (partially) corroborated. While for mainstream parties - PS and PSD - there was a decline in labor representatives inside the party during the crisis, the inverse is true for the radical left parties.

Figure 6 Boxplot of the centrality of union members inside each party, before and after the crisis. Source: Author’s elaboration.

We believe these findings are in line with - and support - two general trends that have characterized the evolution of political parties and interest groups. On the one hand, the main governing parties (PS and PSD) display weaker ties that reflect the priority given to electoral rewards through party platforms that are less ideologically oriented and more closely focused on issues and policy positions in order to appeal to the center of the political spectrum. On the other hand, there has been a growing proliferation of interest groups, especially associations with no political alignment or detached from class-based cleavages, which are increasingly in competition with traditional economic groups (i. e. trade unions and business associations) to represent citizens’ preferences and to gain more visibility (and influence) vis-à-vis policymakers, such as professional associations or cause groups. This trend is confirmed by the increasing proportion of MPs with formal membership in civic society organizations (see Lisi, 2018). Overall, these findings confirm the variation of party-group linkages and the fact that distinct incentives and opportunities are at play for the maintenance of such ties over time.

Conclusions

To what extent do political parties establish ties with interest groups at the leadership level? How do personnel linkages vary in terms of their location and their centrality across distinct parties? Have these ties increased during the crisis? This study addresses these questions by considering an understudied case and drawing from an original dataset. Moreover, we contribute to the theoretical literature by examining a neglected dimension of party-group linkage and by investigating differences across parties and groups, as well as their evolution over time.

Overall, we found that even at the leadership level party-group ties are quite weak, confirming the literature on the anemic interaction between parties and civil society and the lack of structural and organizational party-group ties in newer democracies. The explanation for this pattern has already been addressed by the literature, which focuses on several factors such as access to government positions just after democratization, the reduced party membership and citizens’ distrust toward political parties, among others. By and large, this confirms the findings of the Portuguese case regarding the weak anchorage of political parties vis-à-vis civil society (van Biezen, 2003; Jalali, 2007). The auto-referential character of party politics and the low turnout rate in the main party body (see Lisi, 2015) are also important aspects that help interpret the low degree of permeability between parties and groups at the leadership level. The novelty is that these results apply not only to the extra-parliamentary party but also - to a lesser extent - to the party in public office. The importance of group representatives for the institutional or parliamentary arena may be related to two main factors. Firstly, group leaders can be an electoral asset, i. e., they can bring electoral benefits to the party by strengthening the linkages with specific constituencies. Secondly, they can provide expertise and key information for the policymaking process, which is a fundamental resource for the establishment of party-group connections.

However, this conclusion comes with a caveat. This work considers the most visible arena of party-group linkages in terms of individual networks, but this may not necessarily correspond to the overlap at the grassroots level. As highlighted in the first part of the article, parties and groups may interact at the membership level rather than in terms of leadership. Indeed, an important proportion of candidates that run in national elections actually belong to some type of interest group. In other words, personnel overlap at the leadership level may not be an ideal strategy because it makes the political alignments between parties and groups more visible. This means that our object of study may be the tip of an iceberg, i. e., the surface of which masks a more profound political alignment if we consider the grassroots level. Therefore, our findings must be interpreted with caution given the complexity and multifaceted nature of political parties.

Another interesting finding is that trade unions are largely the type of organization most closely connected with political parties, especially left-wing actors. There may be several explanations for this. First, it is worth mentioning the legacy of democratization, during which the labor movement played a key role in fostering change and emerged as an important political ally of the main parties. Second, ideological closeness is also important because it represents the common ground for undertaking collective action and mobilizing specific social groups, thus strengthening personal ties. The strong alignment between PCP and CGTP exemplifies the proximity between the two sides at both the leadership and the membership level. The fact that left-wing parties have traditionally prioritized labor issues more than right-wing forces contributed to strengthening this ‘natural’ alliance. Finally, trade unions all over Europe have been quite resilient when considering the overall process of civic disengagement, showing more cohesion and unity than business associations (see Allern and Bale, 2017).

As for the impact of the crisis, we hypothesized that party-group ties, namely between left-wing parties and trade unions, had strengthened. This is only partially confirmed in the case of Portugal, which experienced a deep attack against the welfare state, impactful changes to labor market legislation and the implementation of painful austerity measures, which contributed to the convergence of leftist political actors and the rise of the so-called ‘Geringonça’ (2015-2019), sharing the same priorities and competing for the representation of similar constituencies. Indeed, even if the centrality of trade union leaders seems to increase, the density of leadership overlap seems to be reduced after the crisis.

Having summarized the main results, we should acknowledge the limitations of this study in terms of its generalizability. While the findings are of relevance to other similar countries, especially those based on party-centered representation and historically associated with an ideological fragmentation of its interest organizations, the specific institutional set-up, party system characteristics and the legacy of party building and development are likely to affect party-group relations at the leadership level (see Allern, 2010; Tsakatika and Lisi, 2013; Charalambous and Lamprianou, 2016). Moreover, these kinds of ties are particularly sensitive not only to party strategy but also to party status (government vs. opposition) and the channels of institutional access available in a specific period. This means that there might be reversals in the trends detected for this type of relations; however, these are likely to be contingent and with a limited time span, without altering long-term and systematic patterns.

We should also bear in mind that this is an exploratory study that presents inherent strengths and weaknesses. Although our approach allowed us to gain unexpected insights into party-group relations and to validate theoretically relevant questions, the results have some limits related not only to the period covered in this study but also to the depth of the data included in the analysis. In that sense, future research ought to consider not only other types of interest groups but also go beyond the peak-level representatives of labor and capital. Regarding the latter, information on the leadership of sectoral and/or regional business associations may provide fruitful insights. Moreover, we could not investigate in detail the phenomenon of the ‘revolving door’, i. e., the interaction between top politicians and representatives of business companies, multinationals or international organizations. This would require not only to adopt a broader definition of ‘interest group’, but also to look more in detail at the governmental arena. In addition, it would be interesting to update this study by considering the recent evolution of the Portuguese party system, in particular the emergence of new political actors with parliamentary representation following the 2019 and 2022 legislative elections. Subsequent quantitative studies that include data for local offices, as well as for other countries, would certainly allow for more rigorous hypothesis testing. However, the clear lesson to be drawn from this study is that leadership overlap cannot be neglected and deserves more attention in future studies.15