Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar is an artist, writer and historian of modern South Asia who is Associate Professor of History at Brown University. I met her in 2016 when I spend the academic year of 2016-2017 in Providence (Rhode Island, USA): in the first semester as a visiting scholar in the Department of Portuguese and Brazilian Studies (Michael Teague FLAD/Brown Visiting Professorship). It was during this period that I had the privilege to meet and spend some time with some brilliant women scholars I decided to interview as part of a series that I named “In their own words. Academic women in a global world” and proposed it to Análise Social, which has supported the invaluable work of transcribing the long interviews before I did the editing work. Ariella Aisha Azoulay’s interview was the first to be published in Análise Social, in 2020, shortly after the publication of her book Potential History. Unlearning Imperialism.1 Lina Fruzzetti was next, in 2021.2 The anthropologist who transforms her work into remarkable films as well as books was the first black woman to have tenure at Brown University, not a short venture in a country that is still dealing with serious racial discrimination in all spheres, including the higher education level.

What these women had in common was that they are all at Brown University, in different positions and departments, but came from places in the world far from the US and Europe. They were born and raised in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, and all had a reflexive, historical, and politicized relationship with the place where they were born in and resided for some part of their lives. Some had been in the US for many years, decades often, after going there to study a first degree - that was the case of Lina Fruzzetti from Sudan, and Vazira Zamindar from Pakistan. Meltem Toksoz, on the other hand, a Turkish historian, had lived in the US for a few years, earned her doctorate there, but then returned to Turkey. In 2016-2017 she was at Brown Center for Middle East Studies at Brown University (2016-2017) and now she is a Visiting Associate Professor of History at Wesleyan University. Others, like Ariella Azoulay had already studied and taught elsewhere in the world and in the US, before being appointed by Brown as part of a recent university policy to hire exceptional academic women.

Since these interviews were done in the form of a colloquial conversation, rather than with a predefined rigid script, I chose to “withdraw” from the text as the person asking the questions, listening, and guiding the conversation. The interviews were transformed into direct speech in which the different themes were edited by me and divided into sub-chapters, and then revised by the interviewed, at the moment of publication. Hence the name I gave to this serie- “In their own words.”3

All of these women scholars impressed me with their intellectual and academic work, as well as for their politicized engagement with the different worlds they related to. Several of them came from places where conflicts have been raging for decades and had made this their object of study and critical reflection - Palestine-Israel, in the case of Azoulay, and India-Pakistan, in the case of Vazira Zamindar, for example. All of them challenged both the past and the present with difficult questions and none of them had followed a straightforward academic path. They all exemplify how work and life can be one and the same and how one can (and should) be both an academic and a citizen. They all defied the comfort of the idyllic and artificial life at an Ivy League university campus, where one can so easily forget about the outside world, and opted, instead, for “restless” paths and interests. And, of course, they were all women in an American context in which Donald Trump’s recent victory, on the 8th of November 2016, reminded us daily of how gender and racial equality, social justice, and the universality of citizenship had to be constantly cared for, protected, and affirmed. “Freedom is a constant struggle”, wrote Angela Davies, the renowned African American anti-racist and civil rights activist who gave a conference at Brown University around the same time I did these interviews.4

Paradoxically, or maybe not, many of the issues and events we discussed in 2017 remain just as relevant today - six years later. Donald Trump is no longer in power but plans to return soon and, meanwhile, his supporters are thriving, encouraged by the knowledge that he and his ideas can win elections democratically. Not even events such as the Capitol invasion, on the 6th of January 2021, with its massive national and international condemnation, or Trump’s continuous proof of disregard and sexual violence against women, have been strong enough to categorically eradicate the possibility of a Trump comeback. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict, at the center of Azoulay’s work, continues just as pressing as ever before. Recep Tayyip Erdogan is still ruling in Turkey. Just as I am writing these lines, on the 14th of May 2023, Erdogan is being subject to national elections in a country where his political practices and ideas - 20 years in power now - have jeopardized the possibility of a democratic Turkey. A second round of elections will answer the difficult question of if it is possible to overturn an authoritarian leader with elections that are not reliable. On the other hand, the conflicts and tensions between India and Pakistan, which are at the core of Zamindar’s work, only intensified with the “Hindu India” idealized by Narendra Modi, in power since 2014. In his project about the Hinduization of India, Muslim Indians are the greatest victims, even if the country is officially secular. Next year, in 2024, Modi will have to go through his third round of legislative elections to reaffirm his authority. However, only a few months ago, in December 2022, his party, Bharatiya Janata (BJP), had astonishing positive results in the State of Gujarate, Modi’s birth state.

The third interviewee of this series is the historian Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar. Her itinerary is paradigmatic in the ways in which she demonstrates History’s pertinence to the reflection and action on our present. Her first book was titled The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia: Refugees, Boundaries, Histories and it was first published by Columbia University Press in 2007, before having English editions in India and Pakistan a year later, and, in 2014, also in Urdu. The publication was the outcome of her PhD thesis completed at the Anthropology Department of Columbia University in 1997, and it has become a reference for the specific field of decolonization in South Asia as well as for the wider topic that intersects ideas of nation, frontiers, minorities, refugees, displacement, and migration. Through a combination of oral histories and archival research, Zamindar examines the meaning of refugees in nation-state formation of Pakistan and India, after the Partition of 1947.

The impact of the book went beyond academia. Some of the individual stories from the book were transformed into performances by the Delhi-based Dastangoi (Dastaan-e-Partition).5 Mara Ahmad’s film A Thin Wall (2015) was also inspired by the book.6 It was written and directed by Ahmed, an independent writer and filmmaker based in New York, and co-produced by Surbhi Dewan, both descendants of families torn apart by Partition. The film, shot on both sides of the border, in India and Pakistan, is “a documentary about memory, history and the possibility of reconciliation” through the stories that have passed from generation to generation since the division of India in 1947. The Long Partition was also an inspiration for Shayma Sayid’s dance Kanhaiya yaad hai kuch bhee hamari [Krishna, do you ever think of me] which was staged at the South Bank Center, London, in 2017, and for the San Francisco Enacte Arts’ play The Parting, in 2018.7

Another example of Vazira Zamindar’s capacity to build bridges with other creative minds beyond academia is her collaboration with the Indian graphic novelist Sarnath Banerjee, who refers to Vazira’s first publication as “this amazing book on partition, called The Long Partition.”8 Banerjee has a special interest in history and is setting up a project where 10 historians - Vazira Zamindar is one of them - work with 10 visual artists, as well as professionals animators, illustrators, set designers, architectural model makers, or fashion designers. They also plan to collaborate on a graphic novel on the relationship between Gandhi and Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988), also known as the “Frontier Gandhi” because of his nonviolent active resistance against British colonial rule in India. Khan, the Pashtun independence activist was a Muslim who believed in a multi-religious India and opposed the idea of Partition.

As Vazira explains in this interview, she always had an interest in history and her first degree, at Wellesley College, US, with a year at the University of Cambridge, was in Art History. Her second book, Anti-colonial: Image Archive and the Writing of Indian History is the result and testimony of her earlier interests. It continues some of the subjects of her first book - anticolonial struggles, unsettled borders, and the destructive effects of war and conflict - but adds material and visual documents to other written ones, as source and subject. Photographs and colonial films but also museum catalogs, government records, ethnographic dictionaries, military manuals, war albums, as well as contemporary documentation from the author’s own fieldwork on the “frontier” were used to track the effects of the extraction of Gandharan objects from the Indo-Afghan border, in different contexts, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. War and colonialism in the region have had effects in the migration of objects, many of them to European collections, but also in the definition of “Indian art” in different geographies and temporalities.

It was this work that led Vazira Zamindar’s reflections on Gandharan art in European collections and to her role in the Brown University-based project Decolonial Initiative on Migration of Objects and People.9 The Decolonial Initiative came together after a Teaching experience on Decolonizing the Museum organized in 2019 by Ariella Azoulay (Modern Culture and Media/Comparative Literature), Yannis Hamilakis (Archaeology/Modern Greek Studies), and Vazira Zamindar (History), at Brown University. The project brought “together two trajectories of migration, often forced, which are thought of as unrelated and usually studied separately by scholars from different disciplines in the humanities, arts and social sciences”. The first is the migration of objects and the second is the migration of people. As part of Zamindar’s ethos and practice, her written research multiplied in diverse paths, from community and university service to teaching, and to creative collaborations with artists and critical conversations with museums.10

Vazira Fazila-Yacoobali Zamindar’s interest in art history and the visual in South Asia has also manifested in other ways. She coordinated an interdisciplinary reading group on “Theory from the South” (2013-2016), which led to a lecture series and course “Art History from the South” (2018-2020). The latter focused on institutions and practices of art. In Fall of 2018, she also co-organized an international symposium with visiting scholar Tapati Guha-Thakurta from Kolkatta, India, and that has resulted in the co-edited book How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History and Religion in South Asia, published by Cambridge University Press in 2023. Proceedings from another collaborative symposium, this time with RISD colleagues in Fall 2020, are soon to be published as a special issue of the Art Margins magazine, on “Art History, Postcolonialism and the Global Turn”.11 Her interest in the arts and art history has also led her to write on specific artists, such as the well-known Pakistani prolific 20th century artist and poet Sadequain [Sadequain Naqqash] (1930-1987), known for his calligraphic style, and on the Muslim Indian artist based in the US, Zarina [Zarina Hashmi] (1937-2020), whose work Vazira considers to be “an attempt to explain exile in the enduring constitutive violence of partition, one that requires grappling with the ‘minority’ question at its heart, and what it means to long for ‘home’ as a place one can travel to but never return […].”12 Zarina’s family, like Vazira’s, was “one of millions whose lives were controlled, disrupted, and/or destroyed by British imperialism, Partition, and its aftermath.”13 In this essay, Zamindar continues to struggle with the deeply personal experience of partition, as well as its political consequences of dividing a multi-religious society on the basis of religion.

Pakistani cinema is also an intrinsic part of Zamindar’s itinerary. When she directed the Brown South Asian Studies Program from 2012 to 2016,14 she co-organized the Brown-Harvard Pakistani Film Festivals of 2014 and 2015, alongside the anthropologist Asad Ali. This project was turned into the book they both co-edited: Love, War and Other Longings, with essays on cinema in Pakistan (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Zamindar’s teaching at Brown has included undergraduate and graduate courses, individually led and co-taught. Some have concentrated on more specific subjects such as the “History of Colonialism and Nationalism in South Asia, including the Partition of 1947 and Gandhi”, while others, have focused on broader subjects such as “Decolonizing Minds: A People’s History of the World” (with Naoko Shibusawa, the Associate Professor of History, in American and Ethnic Studies);15 “Power, Culture, History”; “The Theory and Practice of History”; and “Refugees: A Twentieth Century History”, a lecture course which “locates the emergence of the figure of the refugee in histories of border-making, nation-state formation and political conflicts across the twentieth century to understand how displacement and humanitarianism came to be organized as international responses to forms of exclusion, war, disaster and inequality.”

As is proven by her itinerary, Zamindar is a holistic academic, engaged with the transformation of her research work into multiple formats of knowledge and creativity, in, out, and in-between the university. Her commitment to public engagement is always present but some moments have been crucial, as has happened with the Occupy movement, as she tells in this interview. By publishing both in the best scholarly venues as well as in newspapers and magazines such as e-flux, Hyperallergic, Third Text Online, Times of India, The News, Dawn, Time Out Delhi, Caravan, Current History or The Wire, Zamindar’s work has reached different audiences. She has also been invited to participate in the radio program Open Source with Christopher Lydon 16 - “India-Pakistan: Vazira Zamindar on the raw wound of Partition” - and in the BBC Radio 4 series and podcast, Museum of Lost Objects, which traces the “histories of antiquities and landmarks that have been destroyed or looted in Iraq and Syria, India and Pakistan.” The histories she writes are always those that can stake a claim on the present and the future, to make possible plural and just worlds where we can “live together” again.

Encounters

I had never expected to go into academia as I do not come from a family where anyone is a writer or scholar. I mean, there were expectations that I would go to college but to actually have any aspirations to research or write, or to be a writer of any kind, that was outside our worldview. And so, it took many years after I finished my undergraduate studies, a series of experiences and encounters that led me to graduate school, and in that sense, my research is really driven by those life experiences - there were questions that made me go to graduate school.

I come from a Gujrati-speaking community and grew up in a family and a community that is divided between India and Pakistan. So, we were always trying to go to the other side to see our family and loved ones or have them come to visit us. Karachi is a city where almost everyone is a refugee from some part of the subcontinent, shaped by its partitions and displacements, and heavy, with tumultuous stories. I grew up with those stories and I remember how my grandmother and other older women in the family would sit around in the quiet afternoons and tell their stories and they would cry, and they would hug each other, and they would cajole each other for crying over the past! When I was studying in the US as an undergraduate, Karachi kept calling me and I dreamt about my grandmothers. I really just wanted to come back and listen to the stories I had grown up with. When I returned to Karachi, it was after the end of the military dictatorship - General Zia had blown up in an airplane - and there was just a huge surge of creativity and experimentation in the city. But this was also the time when the Babri mosque in Ayodhya was torn down. My entire family had gathered in Bombay for my cousin’s wedding that winter, and they found themselves in the midst of the terrible communal violence that followed; its trauma cast a huge silent shadow on our divided family.

Feminism from the south

Feminism has been, of course, incredibly important especially because my mother was the first woman in her family to have a higher education - she went from Bombay to Delhi to study at an all-women’s medical school - and it was an exciting time of change, the 1960s, but it brought new struggles with it. It was extraordinary to have a working professional mother and her struggles at home, as a woman in the workplace, as well as in the national context, was very formative for me.

My mother’s generation of middle-class women created a number of women’s organizations, and they began to organize during General Zia’s dictatorship in the 1980s, especially against laws that were being introduced in the name of religion which discriminated against women. The Women’s Action Forum was perhaps the most important.17 Over the years I found mentors and friends amongst these women and worked for a legal aid organization and a street theater group that was trying to mobilize around violence against women.

One could argue that the history of women’s movements needs to be located in relation to anticolonial mobilizations which brought a lot of women into politics and public service. When these anticolonial struggles achieved national independence, this independence also came with universal enfranchisement. Women immediately got the voting right as opposed to many parts of the West where women did not get voting rights until much later. Thinking with the anticolonial roots of feminist thought in the region is important because of imperialism’s entanglements with women’s emancipation: the idea of “saving” women in societies cast as “backward and traditional” has been a major trope of colonialism. For example, the invasion of Afghanistan was partially justified as liberating women in Afghanistan. And so, a quiet feminism that shapes my own work is inseparable from its anti-imperialist and anti-racist lineaments.

Theater in karachi: listening to stories

I began working in theater when I was in high school - those were the years of the military dictatorship when everything had to go through a censor board, and there were very few places where you could do any kind of theater work. At the time, I worked for Rafi Peer Theatre Company, which was a puppet theater company, but which also provided technical support for theatrical productions. One of the productions I worked on was an adaptation of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the Thomas Hardy book, which had been adapted to Urdu and was being dramatized for this little theater inside the Pakistan-American Cultural Centre, which was called PACC by its initials.

Some progressive theater groups emerged at this time, like Dastak and Ajoka, which were doing adaptations of, say Brecht, but I did not know them as a teenager. There were also many artists and writers in exile at this time. Then the dictatorship ended, and the first elections after more than a decade took place and the young Benazir Bhutto came to power. And this was a very, very important moment. When I returned from the US there was this efflorescence of activity in the city. One of the theatre groups that was very important for the city and for me was called Tehrik-e-Niswan (Women’s Movement), and they started working with neighborhoods and writing plays of their own from the local context, capturing the stories of the city. In the 1990s, there was a lot of conflict and violence in Karachi between different ethnic groups, and they were capturing those stories by doing workshops, theater workshops, in neighborhoods and then transforming them into plays. For one of the plays, called Yahan Se Shehar Ko Dekho (See the City from here), the great Indian artist M. F. Husain came and painted his famous horses for the sets of the play - I remember we would go to the garden of the Goethe Institute to watch him paint as if his painting was part of the play itself!

Tehrik-e-Niswan, street theater and community theater exposed me to different parts of the city, different sections of society. And it made me want to travel in the region and get to know it from outside the comforts of middle- -class life. So, when I got a job at a research center in Islamabad (where I worked on the national career of the artist Sadequain), I also began walking in the mountains in the north of the city. On one of the long treks, I walked up to the Tibetan plateau, to Mount Kailash, Mansarovar and Lhasa, and that is where I became acutely aware that there were histories that belonged to me that I was unaware of, and I began to ask why that was the case. Was it a result of colonialism? Was it a result of partition and the partitioning of the past? For instance, in Tibetan monasteries I received so much love and warmth because Padmasambhava had come from the Swat valley and brought Buddhism to Tibet - but I was totally ignorant of these connections. While I was in Tibet, I met an anthropology student from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, doing her fieldwork there and, as we walked together for some weeks, she convinced me that I should apply to PhD programs in the US.

The long walk: family histories

I got into the doctoral program in Anthropology and History at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and when I initially returned to the US in 1995, it was to study Sanskrit and early Indian history (Buddhism in particular) in this inter- disciplinary program that thought about the entanglements of the past in the present. However, after a few years when some of the faculty that worked on the modern period in the program decided to move to Columbia, I had to decide which period I was going to work on. And this was a really hard decision. I was really interested in early Indian history as a way to overcome the Hindu-Muslim partition of history, but I was also moved by the historiographical questions Subaltern Studies was asking at the time. By moving to Columbia University, I became a twentieth-century scholar and came to the Hindu-Muslim divide through the partition of ’47 and the stories I had grown up with. Partition stories seemed to be everywhere and yet they were completely unrepresented at the time in the political and public debates about how we had become three nation-states. Instead of my own Gujarati-speaking community from Bombay, I focused on north Indian, Urdu-speaking families that I had grown up with as well. I picked the cities of Delhi and Karachi because they were familiar to me and yet a little bit less intimate than my own family’s geography.

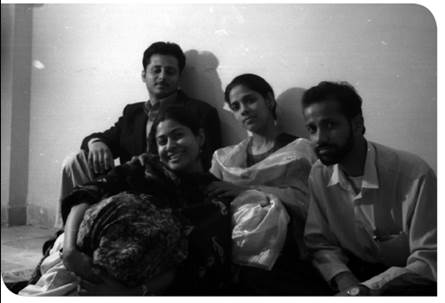

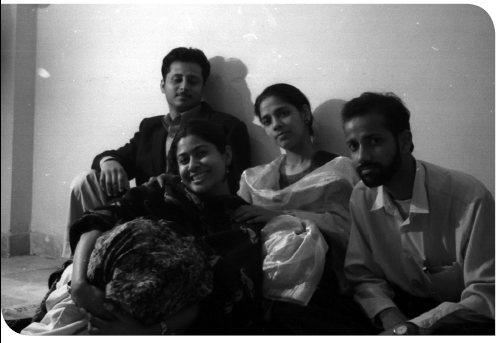

With Attia Rais, my research assistant, and her family in old Dehli, 1998.

I started moving between the two cities, Delhi and Karachi. I conducted oral histories with families in Karachi and then I went and met their family members who had remained in India. In turn, when I got to know other divided families in Delhi, I went and interviewed their family members in Karachi as well, and so I moved back and forth for two years between the two cities. While recording these family histories, I was also interested in understanding what was happening at the state level. And so, I was searching for archives, and trying to read newspapers or government documents of the time, and this was not always easy for the postcolonial period. However, the oral histories grounded me and gave me a particular line of sight in archives. It made me realize that there was a whole process of nation-state formation that was deeply intertwined with displacement, with the mass displacement of partition, and the violence of partition. It gave me an understanding of my own family stories, of the kinds of loss that came with an intractable border, and of the history of the India-Pakistan border.

The long partition: refugees and minorities

The dissertation then became the book The Long Partition and the Making of Modern South Asia. Refugees, Boundaries, Histories (Columbia University Press, 2007). When it came out in 2007, it generated debate and had an impact on the new scholarship that was emerging at the time. When we think of the border between India and Pakistan, for example, we realize it is impossible to represent the difference between an Indian and a Pakistani. It is not religion, because there are as many Muslims in India as there are in Pakistan, and it is not ethnicity, so the border does not articulate a representable limit. Therefore, over the years a highly surveilled and difficult border has come to be constructed and which generates both internal violence as well as against an external other.

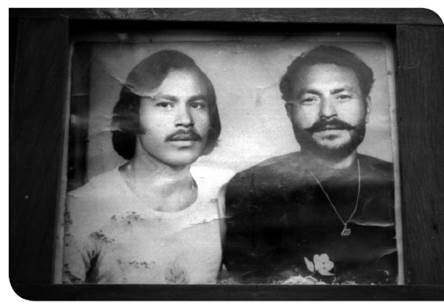

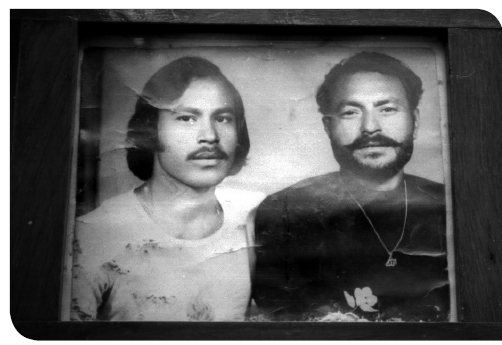

Photograph in Zaheer’s home in Karachi, of him with his older brother Zaheer in Kanpur (for whom he was named after the family was divided),1985 © Vazira Zamindar

The Long Partition placed the Muslim question, which is at the heart of partition, as a problem that was not solved with the drawing of the line. Of course, we knew that the so-called “minority problem” had persisted after partition, but the specific- ity by which the partition and the making, management, and care of refugees, had shaped post-colonial citizenship was not understood. The book was also a very close study of the cities themselves, of the transformation of urban geographies with looting and regimes of dispossession, and of the other kinds of violence that had accompanied genocidal civil strife. I tried to understand the role of the State and State violence in what unfolded, including what I call bureaucratic forms of violence, the dark underbelly of political debates on national belonging and citizenship. Over the last decade, there has been a burgeoning of scholarship that has looked at the transformation of cities, histories of refugees and refugee rehabilitation in different regions of South Asia and the specificity of different borders and borderlands.

The book places at the center those made liminal in this new cartography of nation-states, and one of those characters is an artificial limb-maker, a prosthesis maker. It is a very special story of a man who recovers after a catastrophic loss of a limb and his attempts to make himself whole after dismemberment.This artificial limb-maker was a Muslim, but the Indian State refused to recognize him as Indian, and the Pakistani State also refused to recognize him as Pakistani, and he was constantly deported to the “other” side. His story - of a man who both states disavow - has been performed by some theater groups and written about by others. I think it goes to the heart of the angst of partition itself.

There are parts of that story that I keep coming back to, that pull me and demand continuous reflection. There is an immediate political problem because of the nationalizing of history, the nation frames within which we think about politics and political change, need to be disrupted. In this particularly majoritarian, ethno-nationalist moment, we need to think beyond this frame.

After The Long Partition, I started to think less in terms of partition and more in terms of the figure of the “refugee”. The category of refugee was important for the book, to insist that South Asia be included in the burgeoning field of Refugee Studies, and for thinking with the twentieth century as a whole. But I was much more South Asia focused, even as I was drawing upon scholarships in other parts of the world. However, over the years of teaching a global history of refugees, I began to move away from a comparative framework to an interconnected interrogation of how political ideas moved from place to place to devastating consequences. My class, entitled “Refugees: A Twentieth Century History”,18 has helped me widen my geographical and chronological span, and a book of the same title is under contract with Cambridge University Press.

Another line of inquiry that I am very interested in is that of the “minority”. Partition was meant to solve “the minority problem” but paradoxically it intensified violence against religious minorities in both nation-states. I join others in asking what a minority is, and where and when does it emerge as a political concept, a distinct kind of problem for the postcolonial nation-state. The history of minority offers another way to interrogate the nation form, and engage with its global history. Hannah Arendt helped me a great deal to understand how minority, refugee and statelessness could be related terms, such that the minor, ever-present, could be potentially on the verge of expulsion. But the ways in which the concept takes shape and form in South Asia in relation to its global itinerary interests me deeply.

Now after more than a decade, I think it is also time, I feel, to return to my own family stories, the stories of loved ones which I had been very hesitant to use in The Long Partition. During my dissertation research, I did formal oral histories with my own family, and I traveled frequently between Karachi and Bombay to do this as an aside project. Within this context, I also collected old family photographs and documents, especially from the older members of the family, some of whom have now passed away. In those days, I did it just with an analog camera and an old cassette recorder. But there was one important death in my family at that time and the grief made writing about it extremely difficult. But I think its time has come.

Eventually I would also like to digitize all the archival research I did - realms of photocopies and hand notes, as well as photographs and cassettes, and make it accessible within an institutional context. It is difficult, and sometimes impossible, for scholars of the region to cross the India-Pakistan border, and I have been extremely fortunate to have been able to do so. So, I hope digital access could help others. I have been supporting the Partition Archive in California in an advisory role, largely because it overcame the difficult border by crowdsourcing oral histories work, paying people in different regions to go out and collect oral histories in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, and also the diaspora in the US and elsewhere.19

The art of war/visual archive

Given my prior interest in early Indian history, I began working on a book project on the “Greco-Buddhist” or Gandhara material remains in the northwest of Pakistan. After the Bamiyan Buddhas were destroyed by the Taliban in Afghanistan, I thought I would do my research in a region called the Swat Valley where Padmasambhava was from, famous for its Buddhist material culture and a very beautiful mountain region. However, soon after I started the project the Taliban took over20 this region in Pakistan, and the Pakistani army started a military operation against them. It became very difficult to go and do ethnographic research, and so this became an archive-based project, although I did travel to Peshawar several times over the years.

I was interested in the history of archaeology and art history, the knowledge formations that shaped Gandhara, as well as the military context of the region, a region where there was an armed insurgency against British colonial rule, as well as a very significant Gandhian non-violent mobilization. Certainly, the NATO forces and the US military in Iraq and Afghanistan constantly referred to the British experience on the frontier and self-consciously drew continuities with it. While working in the colonial archive, I began to encounter a huge body of visual materials - photographs, drawings, maps, lithographs, as well as films. That is why this book works with this visual material and engages with both art history and artistic practice in doing so. Using some of the visual material as inspiration, I am also working with a graphic novelist to make a graphic novel about the relationship of Gandhi to Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the anti-colonial leader of the non-violent mobilization (of the Khudai Khidmatgars) in the region.

With the conviction that visual and material artifacts are extremely important to political and historical formations, I have been building collaborations and working with a number of contemporary artists. In the summer of 2012, Asad Ali (an anthropologist at Harvard) and I met a group of young film-makers in Karachi and they inspired us to co-organize Love, War and Other Longings, the Brown-Harvard Pakistani Film Festivals in 2014 and 2015. This was such a labor of love and it brought together scholars and different kinds of film-makers (including Lina Fruzetti), so the edited book that followed tries to capture its experimental energy. Then I initiated a series called Art History from the South which ran from 2018 to 2020 and as part of that I co-organized a symposium at the Cogut Institute for the Humanities with visiting scholar Tapati Guha-Thakurta entitled “How Secular is Art?” in October 2018. Guha-Thakurta was at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, in Calcutta, and her books Monuments, Objects, Histories: Art in Colonial and Post-Colonial India (Cambridge University Press, 2004), and The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal, c.1850-1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2007) had been really important to me. 21 The symposium brought together art historians, historians and anthropologists who were working with visual cultures of South Asia and was so fiery that it felt important to give those hugely significant debates the form of a book. The pandemic certainly took its toll and was extremely difficult for so many of us. So the recent publication with Tapati Guha-Thakurta of How Secular is Art? On the Politics of Art, History and Religion in South Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2023) feels like a real achievement against all odds.

Decolonial initiatives at Brown

I have always strived to be politically engaged in the world, partly on the principle that it forges your relationship to a place, wherever you are. It connects you to the kinds of people that you want to spend time with! When I joined Brown, it shaped my teaching and the kinds of questions I wanted to ask in my classes. Many of my students in my classes at the time, for example, were from the Student Labor Alliance,22 and I joined them in the organized protests of the Occupy Movement. Occupy was really important for me, and for many of us on campus, it felt like a moment when we were part of a nationwide mobilization. The Arab Spring had just happened before Occupy and following the developments of the Arab Spring and Occupy, where I was very involved, it had an impact on my teaching at Brown. When Occupy happened we - faculty and students -organized a massive teach-in on Campus and then became very active with community organizations in Providence that were occupying Burnside Park downtown.23 It was roughly a six-month period when some professors, students and community activists came together and it was exhilarating. We were asking how do we sustain a social movement; how do social movements build solidarity and how do they make connections with social movements elsewhere. We were asking these questions through an amazing set of artistic and cultural activities, energies that were being brought together by this movement. In the winter of Occupy, as the students were leaving for winter break, we had a big conversation with them about what the winter was going to mean for this movement, and we feared it would fade but we felt like there had to be some conversation, intellectually at least, to continue to think with that movement.

Of course, it petered out that winter, there were warnings from the City of Providence authorities, and they were removed from downtown Providence. My colleague Naoko Shibusawa24 and I, who had both been involved together all the way through the Occupy movement, developed a course named Decolonising Minds: A People’s History of the World in response to the questions students were asking us. We wanted to create a course that would think about capitalism and colonialism together, as well as the struggles against capitalism and colonialism. Thus “decolonizing” in the title of the course, which we took from Ngugi wa Thiongo’s famous book of that name, and “people’s history” drew on the American historian Howard Zinn. We taught “Decolonising Minds” for the first time in 2012 and taught it for the next five years together. It attracted students who were politically active on campus and wanted historical tools to deepen their understanding as well as think globally. So, in the very first semester, we had mostly the students who had been active with us in the Occupy movement, and we were all reading together like a reading group. But in the second year, the word spread and a lot of different kinds of student activists applied, wanting to get into the class. We got up to a hundred students who applied to get into this 20-person seminar, and it developed a reputation and became a community of sorts. Every year different kinds of politically and socially engaged students joined us in reading, from Marx to Michel-Rolph Trouillot,25 histories of slavery and contemporary farmer suicides in India, Cedric Robinson on racial capitalism and Cathy Lutz on bases of empire. We both learned a lot from the materials we taught and from our students. Rather than presume that there was something readily available that we might teach as “global history” we were self-aware that teaching under that framework was also an argument to not just think about the political present in national terms but through the entanglements of colonialism and the anti-colonial struggle.

A few years later, I got to know my colleagues Ariella Azoulay and Yannis Hamilakis through a Pembroke seminar, and here we found connections with each other with our interests in both refugees as well as in material culture and the visual record. After the Sarr-Savoy report came out, we organized together a teach-in on “Decolonizing the Museum”. The energy and interest at the teach-in led us to continue the conversations through a Decolonial Initiative on the Migration of People and Objects. The Decolonial Initiative has coincided with student initiatives to decolonize the curriculum, and these remain vital conversations on campus and beyond.

There must be other ways of imagining how we live in the world and how we live together. Because how we live together in the age of forced migrations and climate change is perhaps one of the most important questions of our times. We must figure out and forge ways of living together with all the differences that we have across our planet. Why is living together still such a fraught question? We do have the history of colonialism to grapple with at the heart of it all, and so “decolonizing” as such is a process that we need to engage with every step of the way. One could argue that the widening of the use of the term “to decolonize” has diffused and weakened its meaning, and so it is helpful to anchor it in anticolonial thought from across the twentieth century and to think with it creatively as our shared inheritance for forging the twenty-first.