Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versión impresa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra n.88 Lisboa 2009

Environment based innovation. Policy questions

Argentino Pessoa [i]; Mário Rui Silva[i]

[i] CEDRES, Faculdade de Economia do Porto, Universidade do Porto. E-mail: apessoa@fep.up.pt; mrui@fep.up.pt

ABSTRACT – Natural resources and physical cultural resources, referred to in this paper as Environmental Resources, can be important assets for regional competitiveness and innovation. In recent years, these types of assets have been increasingly taken into consideration in the design and implementation of regional development strategies, as a consequence of their potential role as a source of differentiation and of new competitive advantages. However, in contrast to environmental policies, which usually focus on the protection of the environment, innovation policies and their instruments are largely shaped by, and geared towards, knowledge-based innovation. In this paper, we discuss the role played by environmental resources in the context of regional innovation policies. We begin by discussing the relationship between environmental resources and regional development, and by emphasizing some contrasting views with regard to the function of environmental resources in regional development. Then, we address the relationship between regional competitive advantages and innovation strategies. The specific issues and problems that arise whenever the aim is to attain competitive advantages through the valorisation of environmental resources constitute the core of section III. In that section, we highlight the specific characteristics of environmental resources and we discuss the applicability of the natural resource curse argument to the dynamics based on the valorisation of environmental resources. The reasons that justify public intervention as well as the difficulties concerning the adequate level of intervention (local / regional / national) are also examined. The paper ends with some conclusions and policy implications.

Key words: Competitiveness, environment, innovation, innovation policies, regional development. JEL codes: O3, Q0, Q2, Q5, R5.

Inovação baseada em recursos ambientais. Desafios para a política

RESUMO – Os recursos naturais, a par dos recursos culturais físicos – globalmente designados no contexto desta análise por recursos ambientais – podem constituir activos importantes para a competitividade regional e para a inovação. Verifica-se uma tendência crescente para a consideração destes activos nas estratégias de desenvolvimento regional, uma vez que estes podem constituir uma fonte de diferenciação e de novas vantagens competitivas. Contudo, por contraste com as políticas ambientais, que visam habitualmente a preservação ambiental, as políticas de inovação e os seus instrumentos estão em grande medida formatados para promover a inovação baseada no conhecimento. Neste artigo, discutimos o papel dos recursos ambientais nas políticas regionais de inovação. Começamos por relacionar recursos ambientais e desenvolvimento regional, considerando algumas perspectivas opostas no que se refere a essa relação. Seguidamente, assinalamos a relevância das estratégias de inovação no contexto da criação de vantagens competitivas regionais. As especificidades e problemas associados à promoção de vantagens competitivas através da valorização dos recursos ambientais são o objecto central da análise desenvolvida na secção III. Entre outros aspectos, procuramos clarificar as características económicas dos recursos ambientais e discutimos a aplicabilidade da maldição dos recursos naturais às dinâmicas assentes na valorização de recursos ambientais. As razões que justificam a intervenção pública, bem como as dificuldades inerentes à selecção do nível mais apropriado para essa intervenção (local / regional / nacional), são igualmente examinadas. O artigo termina com um conjunto de conclusões, nas quais se destacam as implicações da análise ao nível das políticas.

Palavras-Chave: Competitividade, ambiente, inovação, políticas de inovação, desenvolvimento regional. Códigos JEL: O3, Q0, Q2, Q5, R5.

Les ressources environnementales en tant que base de linnovation. Un défi politique

RESUME – On entend par ressources environnementales tant les ressources naturelles que la partie physique des ressources culturelles. Elles peuvent être dimportants facteurs de compétitivité régionale et dinnovation et sont aujourdhui davantage prises en compte par les stratégies de développement régional, parce quelles peuvent être la source de différentiations et davantages relatifs. Mais les politiques dinnovation et leurs instruments sont surtout destinés à promouvoir le développement qui est basé sur la connaissance. Quant aux politiques qui prennent en compte les ressources naturelles, elles tendent surtout à leur préservation. On discute le rôle que les ressources environnementales jouent dans les politiques régionales dinnovation. Il existe à ce propos des points de vue opposés. On montre ensuite le rapport existant entre avantages régionaux relatifs et stratégies dinnovation. Le point 3 traite des problèmes liés à la création davantages compétitifs, à partir de la valorisation des ressources environnementales. On cherche à clarifier les aspects économiques de ces dernières et, en particulier, la notion de malédiction des ressources naturelles. Sont examinées les raisons justifiant lintervention publique et les difficultés liées au choix du meilleur niveau dintervention, local, régional ou national. En conclusion, on montre les implications politiques de cette analyse.

Mots-clés: Compétitivité, environnement, innovation, politiques dinnovation, développement régional.

I. ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT

In growth theory, seen as the set of macro-models aiming to explain economic growth at the aggregate level, the reference to natural resources has nearly disappeared. In the Harrod / Solow debate (Harrod, 1939, 1948; Solow, 1956, 1957), per capita growth was attributed to exogenous and unexplained technical progress. Later, human capital accumulation also started to be regarded as a relevant source of economic growth, in accordance with perspectives such as the work of Robert Barro on the determinants of the level of the socalled steady-state product (Barro, 1991; 1997), or Lucas model of endogenous growth (Lucas, 1988). Then, in the second generation of endogenous growth models, the engine of per capita growth is technical knowledge (Romer, 1990; Aghion and Howitt, 1992), the accumulation of which is modelled endogenously.

In fact, natural resources strictu sensu cannot be accumulated and therefore tend to be seen as an exogenous constraint to growth – as indeed they were considered by such classical authors as Ricardo (1817). However, the appraisal of the role and impact of natural resources as an exogenous constraint to growth has taken very contrasting forms. While some social scientists and historians (see for instance Wright, 1990) tend to view natural resources as an endowment of nature that represents an advantage over regions where such resources are in short supply, other look to natural resources as a curse (Sachs and Warner, 2001)[ii].

An analogous appraisal may be made of cultural assets as concerns the lack of attention to the latter as a determinant of economic growth. While culture is a wide concept whose discussion falls outside the scope of the present analysis, cultural assets may include such immaterial elements as the traditions, norms and values that make up group identities, as well as those symbolic elements that serve a meaning purpose. Moreover, cultural assets also include physical objects like art objects and other human built heritage, including for instance the human built rural or urban landscape.

Certain immaterial aspects associated with the concept of institutions have been considered in the economic analysis of growth, within both the institutionalist (Commons, 1931; North, 1990) and even the mainstream neoclassical theoretical frameworks. For instance, the aforementioned work by Barro includes the quality of institutions as a determinant of the level of the steadystate product of economies. However, these analyses stress the role of norms and culture in understanding and explaining institutions such as firms and markets, which is related to but not coincident with the idea of cultural assets as a source of economic value. Moreover, physical cultural assets clearly fall outside the scope of any considerations concerning the role of institutions in growth and development.

Nevertheless, the consideration of natural and cultural assets has been present in development analysis through the contribution of the sustainable development perspective. The concept of sustainable development first gained widespread public attention thanks to the work of the Brundtland Commission, the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED, 1987)[iii]. This Commissions report not only argued that a healthy economy depends on a healthy biosphere and vice versa, but also put forth the idea of sustainability as a means of integrating economic and ecological concerns within long-term development strategies, thereby contributing to the emergence of the new subdiscipline of ecological economics. One of ecological economics key contributions was the concept of natural capital (El Sarafy, 1991) – a form of capital that is distinct from fixed and human capital and which is brought into the analysis by taking account of its particular properties using the common instruments of capital theory. One of the distinctive features of natural capital, according to ecological economists, is precisely its sustainability properties (Costanza and Daly, 1992).

Thus, the concept of natural capital forms the basis for thinking about sustainable development – the management of natural resources in a way that provides for the needs of the present generation without compromising the capacity of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED, 1987: 43). The constitutive elements of natural capital comprise renewable and non-renewable resources, the ecosystems that support and maintain the quality of land, air and water, and biodiversity.

In the early 1990s, another UN Commission, the World Commission on Culture and Development (WCCD, 1995) extended the idea of sustainability to the dominion of culture[iv]. Although the impact of this latter commission upon the public consciousness has not been as significant as that of the Brundtland Commission, it has succeeded in raising a number of questions to do with the relationship between culture and development in somewhat analogous terms, and in placing this debate within that on the broader issue of sustainability.

Ever since this time, the concept of cultural capital has been slowly but surely taking form (Throsby, 1997, 1999, 2003; Shockley, 2004). A piece of cultural capital may be described as any asset that embodies or gives rise to cultural value in addition to whatever economic value it may possess. An example helps make this intuitively clear: a heritage building may have a given commercial value as a piece of real estate, but its true value to individuals or to the community is likely to include artistic, spiritual, symbolic or other elements that may transcend or lie outside of the economic calculus. These values may be regarded as that buildings cultural value. Cultural capital defined in this way may take a tangible form – e.g. buildings, locations, sites, artworks, artifacts, etc. –, or an intangible one – e.g. ideas, practices, beliefs, traditions, etc.

Other authors have highlighted the direct interactions between culture and the environment (Nassauer, 1997; Garcia Mira et al., 2003). While a thorough assessment of this fruitful literature is outside the scope of the present paper, in terms of environmental and economic policy these paradigms imply interpreting the management of cultural capital and natural capital as a matter of defining sustainable development paths for the economy under a variety of assumptions (Solow, 1986; Hartwick, 1995).

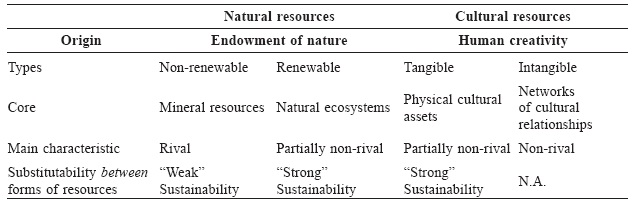

In line with the aforementioned contributions, natural capital includes both non-renewable and renewable resources, while cultural capital includes both physical and immaterial elements. In our analysis, we will deal mainly with natural renewable resources, physical cultural resources and their relevance to economic growth – including, in particular, to regional development. As we will discuss further in section III, renewable natural resources and physical cultural assets share a number of common characteristics (in terms of rivalry and sustainability properties) that set them apart from both exhaustible natural resources (which are characterised by rivalry in their use) and intangible cultural resources (which, like knowledge, are completely non-rival). In the meantime, we shall from now on avoid the use of the term capital, given that, in a more strict sense, this term refers to wealth accumulated and mobilised by economic agents with an investment intention, as occurs in the case of physical and human capital but not in that of natural or cultural resources. Thus, we shall instead refer to the set of natural renewable resources and physical cultural assets as environmental resources.

Though neglected in the context of growth theory and of aggregate analyses of economic dynamics, environmental resources are at the centre of many successful cases of sector and regional growth, and many policy-makers have been increasingly paying attention to them. At the regional development level, it is not difficult to find cases in which the economic valorisation of environment resources has played a major role in economic growth. As for physical cultural assets, obvious examples of their impact upon regional and urban development include those of many city-regions in Italy, including Rome, where investments made several centuries ago – for domestic or infrastructural purposes – have continued to give rise to positive externalities and to generate economic value up until the present today.

Based either on their natural resource endowment or on a combination of natural and cultural resources, several European laggard regions have in the past few decades undergone successful evolutions driven by tourism and tourismrelated activities. For instance, the Algarve and Madeira were in the 1960s two of the poorest regions in Portugal and in Europe; they are now two of the three Portuguese regions with highest GDP per capita and, at the end of the Third CSF period, they ceased to be Objective 1 regions.

In sectoral terms, it is a well-known fact that tourism – an activity that is clearly based on environment resources – is a fast-growing activity with great relevance in terms of job creation. Between 1950 and 2004, the worldwide number of tourists has undergone a 30-fold increase (World Tourism Organization). According to certain estimations, by the year 2000 the tourist industry possibly represented 11% of world GDP and 8% of world employment (Rita, 2000).

The cultural industries associated with art, music, museums, literature and so on already account for more than 7 millions of jobs in the EU (MKW, 2001). These industries may be defined as those activities that are related to the production and distribution of symbolic goods, whose value derives from the function they serve in terms of providing meaning (OConnor, 1999). More recently, the new category of creative industries has been the object of increasing attention as an important filière of activities, which includes not only the cultural sector but also the media and other technological activities in which creativity and culture are the main source of added value.

Policy-makers have also been paying increasing attention to the economic value of environmental resources, regarding them not only as a constraint but also as a relevant asset for growth and development. For instance, in a recent report on the pro-active management of the impact of cultural tourism upon urban resources and economies, Besson and Paskaleva (2005) summarize 33 best-practice cases in a series of European regions.

The European Commission, when recently preparing a Maritime Policy for the Union, declared the need for a wide-ranging policy aimed at developing the maritime economy in an environmentally sustainable manner. Such a policy should be supported by excellence in marine scientific research, technology and innovation. In the same report, the European Commission estimated that between 3% and 5% of Europes GDP is generated by maritime-based industries and services – even without taking into account the value of raw materials such as oil, gas or fish (Commission of the European Communities, 2006). Maritime industries are likely to undergo significant growth in the future, namely due to the growth potential of sectors and activities such as cruise shipping, ports, aquaculture, renewable energy, submarine telecommunications and marine biotechnology (Douglas-Westwood Limited, 2005).

In the next section, we argue that environmental resources can play an important role in fostering regional competitive advantages and regional innovation strategies but also that, at the same time, the use of environmental assets in this process gives rise to some difficult policy questions.

II. REGIONAL COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES AND INNOVATION STRATEGIES

In a recent report published by the European Commission with the appealing title Constructing Regional Advantage, a group of European experts highlight the distinction between comparative advantage, competitive advantage and constructed advantage (Cooke et al, 2006). While comparative advantage corresponds to the Ricardian concept that perceived competitiveness in a static manner, as the result of production factor endowments, the competitive advantage concept was introduced by Porter in order to capture the dynamics of competitiveness. Competitive advantage rests on making more productive use of inputs, which requires continual innovation (Porter, 1998a, p. 78, quoted by Cooke et al., 2006).

In Porters analysis, as well as in other relevant analyses of competitiveness, competitive advantage is regarded as a highly localized, or contextual, process. Other than Porters contribution (1990, 1998b), the analyses structured around the marshallian concept of industrial district – given a new impetus by Becattini (1979) – or the more recent set of analyses around the concept of regional innovation systems (Cooke, 2001) have also stressed this local dimension. However, the consideration of business interactions and networks, knowledge diffusion, collective learning mechanisms and so on are not sufficient to distinguish the concept of competitive advantage from a closely related one – that of constructed advantage. As argued by Cooke et al., the emphasis on constructed advantages stresses the idea that competitive advantages need to be constructed consciously and pro-actively, namely through a more dynamic role of the public sector ( ) generally and government and governance specifically (Cooke et al., 2006, p. 74-74). In the same way and in our opinion, the concept of constructed (competitive) advantage can be a useful one for regional development analysis because, in many cases, not only should the support to innovation in the business sector and the promotion of interactions between different agents be a permanent concern of policy-makers, collective actions and a public coordination role should also integrate the core of policy actions.

The regional innovation system (RIS) concept is a recent one, but it will probably become one of the most influential in the next few years, namely as far as the design of regional development policies is concerned. First, there is no doubt that the RIS concept was to a great extent derived from the previous concept of National Innovation System (Freeman, 1987 and 1995; Lundvall, 1992; Nelson and Rosenberg, 1993). According to Saviotti (1997), an innovation system can be defined as a set of actors and interactions whose main objective is the generation and adoption of innovations. This definition recognizes that innovations are generated not just by individuals, organizations and institutions but also by complex patterns of interactions between them. Thus, for each innovation system it is possible to identify its elements, its interactions, its environment and its frontier.

As argued by Cooke (2001), the recent idea of RIS is the result of a certain degree of convergence between the work of regional scientists, economic geographers and national innovation systems analysts. The relevance of RIS is based on the fact that proximity plays a major role in terms of the density of networks and interactions; this fact is in general attributed to the tacit nature of a relevant part of knowledge. Tacit knowledge is best shared through face-to-face interactions between partners who already share some basic commonalities: the same language, common codes of communication and shared conventions and norms (Asheim and Gertler, 2005, p. 293). The regional dimension also generates a more focused knowledge basis, as a cumulative result of the clustering of economic and innovation-oriented activities. Asheim and Gertler develop analogous arguments and do not hesitate to stress that the more knowledge-intensive the economic activity, the more geographically clustered it tends to be (Asheim and Gertler, 2005, p. 291).

Alongside the cognitive and normative dimensions of RIS, which may be present to a greater or lesser degree, the political dimension should also be taken into account. Cooke (2001) points to the region as a key component of RIS, regarding it as a meso-level political unit set between the national (or federal) and local levels of government, which may or may not have some cultural or historical homogeneity but which possesses the statutory powers to intervene and support economic development, particularly innovation. This political dimension is particularly relevant from the point of view (as discussed above) of constructing regional competitive advantages. We shall therefore keep this aspect in mind throughout the ensuing discussion on the issue of innovation policy based on the valorisation of environmental resources.

Regional innovation policies should be aware of the differentiation of regional paths. Even from a strict knowledge-based economy perspective, regional differentiation is important because the knowledge base of the existing productive sectors is not the same everywhere. Also, some knowledge focus is needed in the Science and Technology public institutions. As pointed out by many authors, cumulativeness and path dependency are important characteristics of technological capabilities.

The endowment in terms of environmental resources can constitute another source of differentiation of regional development paths. Contrary to capital, which is a generic resource, environmental resources exhibit specificities and can, therefore, act as a source of regional competitive advantages. The economic valorisation of environmental resources and their combination with knowledge can lead to specific innovation paths. However, regional innovation policies and instruments are shaped in a quite generic way and essentially geared towards knowledge-based innovation, with an emphasis on cognitive aspects. Because the nature and use of environmental resources presents some singularities, their economic valorisation has a number of specific implications for innovation policies.

III. CONSTRUCTING COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGES THROUGH ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCE VALORISATION: SPECIFICITIES AND PROBLEMS

Environmental resources have certain specific characteristics that must be taken into account when these resources are used. Thus, we begin this section by discussing the scope and characteristics of environmental resources, focusing on the rivalry, sustainability and substitutability dimensions.

Because the economic history of the last two centuries shows mixed evidence as far as the effects of natural resources endowment upon growth and development are concerned, we proceed by addressing the reasons for this contradictory evidence. As a matter of fact, during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century, several countries went through development experiences in which natural resources seem to have been the engine of economic growth. The most notable cases include Australia, Scandinavia and the United States (Wright, 1990; Blomstrom and Meller, 1990). However, it is hard to find similar successful development experiences in the second half of the twentieth century. Indeed, in many countries the natural resource sector has been allegedly responsible for the underdevelopment or slow growth of the economy, leading to the emergence of the idea of a natural resource curse. An important question that arises in this context is: are the mechanisms that generate this curse present when development is based on the economic valorization of environmental resources?

Building competitive advantages depends not only on putting inputs to a more productive use, but also on the dynamic effects of that use upon the economy. Consequently, the third part of this section addresses the externalities caused by the use of environmental resources. In the presence of either externalities or public goods, economic theory calls for public intervention. However, building sustained development paths through the use of environmental resources gives rise to another, not less important, question: what is the appropriated level for public intervention? Is it the local / regional or the national level? This section concludes with a brief reflection on this latter issue.

1. The scope and characteristics of environmental resources

A key element of the aforementioned sustainable development perspective when applied to natural resources is the concept of equity in the treatment of different generations over time, i.e. the principle of intergenerational equity (Pearce and Turner, 1990). However, in addition to intergenerational aspects, the notion of ecological sustainability also implies several other principles, including equity within the present generation, the conservation of biodiversity and observance of the precautionary principle, i.e. the adoption of a risk-averse attitude when confronted with decisions that may cause irreversible change (ORiordan and Jordan, 1995). Similar principles can be applied to cultural resources, insofar as the stock of cultural assets, both tangible and intangible, embodies the culture that we have inherited from our ancestors and which we pass on to future generations[v].

It can be argued that much in the same way as natural ecosystems support the real economy, so do cultural systems, regarded as networks of cultural relationships and institutions that spread through societies, play an essential role in sustaining economic activity. In other words, when cultural systems function well, human productivity and economic growth are enhanced. But there is another parallel between natural and cultural resources: both are related to wealth that has been inherited from the distant or recent past – the former provided as an endowment of nature, the latter deriving from human creativity. However, in spite of these similarities, the two types of resources are characterized by a certain degree of heterogeneity. On the one hand, natural resources are either renewable or non-renewable; on the other, cultural resources may take either a tangible or an intangible form.

As already mentioned, this paper deals with environmental resources, defined as the set of natural renewable resources and physical cultural assets. Why defining the object of our attention in this way? As is apparent from table I, which presents the similarities and differences between natural and cultural assets, the definition has to do with the main characteristics of each type of resource. While non-renewable natural resources (e.g. mineral resources) are rival goods, renewable natural resources, (e.g. the sun or the landscape) are partially non-rival. This latter attribute is a characteristic of tangible cultural assets as well. Moreover, culture is generally intangible (like knowledge) and therefore non-rival.

Table I – Natural and cultural assets.

Quadro I – Bens naturais e culturais.

In economic terms, a sustainable development path can be defined as a situation where aggregate consumption is less than, or equal to, the net domestic product. Consequently, sustainability requires that the total stock of resources is kept at least at its current level. If the stock of resources is regarded as including human, cultural and natural assets as well as physical capital, the question arises as to whether different types of assets can simply be aggregated, such that a decline in the level of one type of resources can be compensated for by an increase in another. In other words, this raises the issue of substitutability between forms of assets[vi].

Within the literature on the substitutability between natural resources and human-made capital, two main paradigms have emerged (Neumayer, 2003). The first, which may be labelled weak sustainability, derives from the seminal work by Solow (1974a, 1974b) and Hartwick (1977, 1978)[vii]. These authors investigated the question of investing the rents from exhaustible resources in the presence of the need for intergenerational equity. In its simplest form, this model portrays an economy in which the competitive rents from the current use of the exhaustible resources are reinvested in human-made capital goods, thus enabling society to maintain a constant consumption stream; the accumulation of physical capital exactly offsets the decline in natural non-renewable resources.

As is apparent, the weak sustainability paradigm assumes that natural resources and human-made capital are perfect or good substitutes in the production of consumption goods and in the direct provision of utility for both present and future generations. This perspective entails a concept of sustainability that is completely different from the ecological one. It is the aggregate capital stock that matters, not what it encompasses; in other words, it doesnt matter if the present generation uses up exhaustible resources, as long as sufficient new physical capital can be provided to future generations by way of compensation.

However, how can the weak sustainability paradigm be applied to the case of cultural assets? It is a fact that, e.g., some of the economic functions provided by a historical building could just as well be performed by some other structure without any cultural content. However, since by definition cultural wealth is distinguished from physical capital by its embodiment and production of cultural value, there would be zero substitutability between cultural assets and physical capital in terms of cultural output, since no other form of capital is capable of providing this sort of value. In other words, because cultural assets by definition give rise to two types of value – namely, economic and cultural –, only the former of these can be substituted for.

Therefore, both natural renewable resources and tangible cultural resources are associated with the strong sustainability paradigm, that is, both forms of resources are regarded as being strictly non-substitutable for human-made capital – a view deriving in part from the unique life-supporting properties of global air, land and water systems. Proponents of strong sustainability argue that no other form of wealth is capable of providing the basic functions that make human, animal and plant life possible. Moreover, some forms of natural renewable resources cannot be reconstructed after they have been destroyed; for example, the destruction of biodiversity is a loss of natural wealth that cannot be reversed and even climate change could result in irreversible damage to the ecosystem.

2. Is the natural resource curse applicable to environmental resources?

The idea that natural resources might be more a curse than a good thing emerged in the 1980s. Since then, the resource curse has been taken to refer to the apparent irony whereby countries with an abundance of natural exhaustible resources exhibit less economic growth than countries without such an endowment[viii]. The alleged negative effects of this natural resource abundance are accounted for through both political and economic arguments.

Firstly, in political terms, and drawing on Kruegers (1974) argument that natural resources provide an easy way of receiving rents and lead to rent-seeking competition rather than productive activities, other authors (Sachs and Warner, 1995; Gray and Kaufmann, 1998; Ascher, 1999; Leite and Weidmann, 1999, Rodriguez and Sachs, 1999; Gylfason, 2001a; Torvik, 2002) have highlighted the fact that natural resource rents create an incentive for economic agents to corrupt the administration in order to gain access to them and that, consequently, natural resources are often associated with the emergence of politically powerful interest groups that attempt to influence politicians prone to corruption in order to adopt policies that go against the general public interest (Mauro, 1998).

Secondly, natural exhaustible resource abundance is taken to pressure some variable or mechanism X that obstructs or delays growth (see Sachs and Warner, 2001). Since abundance of natural resource provides a continuous stream of future wealth, it decreases the need for savings and investments. Yet, world prices for primary commodities tend to be more volatile than world prices for other goods. Therefore, economies based on primary commodity production will tend to experience greater volatility (sharper and more sudden booms and recessions), which in turn creates uncertainty for the potential investors in those economies (Sachs and Warner 1999b). This variable X may consist of either the manufacturing sector, education, or even openness. Natural resource wealth reduces the potential share of the manufacturing sector, for which human capital is an important factor of production. Sachs and Warner (1995) have also argued that natural resource abundance creates a false sense of confidence: easy riches lead to sloth. An expanding primary sector does not need a high-skilled labor force, and there is no pressure to increase spending on education. The need for high-quality education declines, and so do the returns to education (Gylfason 2001a). This restricts both the future expansion of other sectors that require educational quality (Gylfason, 2000, 2001a, 2001b; Sachs and Warner, 1999b) and technological diffusion in the economy (Nelson and Phelps, 1966). Natural resource abundance reduces the openness of an economy and hurts its terms of trade. Since natural resources weaken the manufacturing sector, policy-makers may impose import quotas and tariffs that protect domestic producers in the short run (Auty, 1994; Sachs and Warner, 1995), but which, in the long run, harm the openness of the economy and its integration into the global economy.

Finally, a phenomenon known as Dutch Disease (Sachs and Warner, 1995; Gylfason, 2000, 2001a, 2001b; Rodriguez and Sachs, 1999) may occur as a result of a natural resource boom whenever this boom causes the factors of production to move from the manufacturing sector towards the booming primary sector in response to the increasing rents in the latter. Often, the manufacturing sector is characterized by increasing returns to scale and positive externalities. The contraction of the manufacturing sector further decreases the profitability of investments, thus accelerating the decrease in investment (Sachs and Warner, 1995, 1999a; Gillis et al, 1996; Gylfason, 2000, 2001a). Additionally, natural resource booms increase domestic income and the demand for goods, generating inflation and an overvaluation of the domestic currency. The relative prices of all nontraded goods increase and the terms of trade deteriorate. Exports become more expensive relative to the world market prices and, consequently, decline.

Although resource curse arguments have been largely put forth at the aggregate level of national economies and mainly concern non-renewable resources, they can be extended to the regional context and to the use of environmental resources. Because the expansion of activities based on environmental resources may occur in an extensive way, i.e. without efficiency gains, some crowding-out effects upon other activities subject to competition may arise. Typically, in the case of some small touristy regions, the boom of tourism and tourism-related activities has contributed to the decline of previously-existing activities such as agriculture or manufacturing. In these cases, the crowding-out effects have been felt mainly through the markets for labor and land, due to the fact that the booming sector has generated a strong increase in labor and land prices.

Thus, in order to avoid or minimize these crowding-out effects, the use of environmental resources must be appropriately linked with dynamic efficiency concerns and with innovation. This allows for a less extensive use of environmental resources, as well as for competitiveness to be based not only on an initial resource endowment, but also on innovation. This also increases the range of activities that are related to the environment-based ones and makes it possible to provide them with a greater knowledge-based content.

3. Externalities and the need for public intervention

Environmental resources are a source of positive externalities, i.e. economic benefits accruing to individuals that did not contribute to their production or preservation. However, unless cautiously managed, the use of environmental resources may also give rise to negative externalities, such as additional pressure upon fragile environments, erosion of sites, unwelcome socio-cultural effects, road congestion or the crowding-out of activities of other sectors. Next, we provide some examples of positive and negative externalities by drawing on the case of the tourism industry.

Investments based on the use of environmental resources are typically interdependent. For instance, in the case of rural tourism, each investor benefits from the fact that several sites or farms are available within the same region, insofar as this increases the visibility for external visitors and has a positive impact upon the landscape. In the case of maritime regions, considerable complementarities exist between hotels, restaurants, beach facilities, recreational nautical activities, and so on.

The use of environmental resources can also give rise to positive economic benefits or externalities that accrue to the entire community, e.g. greater awareness of the environment and of the local culture, monument conservation and wildlife preservation (Tisdell, 1983, 1987). Additionally, the economic use of environmental resources may make it possible for other resources to be used and charged for at a price that is greater than their opportunity cost to the community (e.g. if some of those resources were previously not employed). If external visitors are willing to pay a higher price for the use of a particular natural or cultural asset than the rate at which the community currently values it, this effectively constitutes a net gain to the community. For example, if tourism helps bring down unemployment by increasing the demand for labor, there is a net gain as long as the price of this labor is greater than the cost to the economy of making it available.

Partly due to the aforementioned interdependence, investments based on environmental resources can also give rise to negative externalities. Tourism has a major disrupting impact upon the host community and its way of life, in addition to a symbolic dimension that is characteristic of each destination. For this reason, individual projects that do not fit with the existing cultural or symbolic values may have negative effects upon all the other projects and activities.

While tourism fosters the creation of jobs, services and facilities, it may also exert various pressures upon the host community, especially during growth phases. Because the environment has traditionally been regarded as a free public good, the consequence is often excess demand for, and over-utilization of, environmental resources (Buhalis and Fletcher, 1995). Some of the major negative social impacts of tourism include congestion, crowding, noise, pollution, crime and price increases (Brown and Giles, 1994). This is particularly so during the development phase, as local involvement gives in to the interests and pressures of external developers. An increasing ratio of visitors to locals may encourage a decline in tolerance towards tourists – and a high population of temporary workers, particularly during peak seasons, adds to the discomfort. Problems also occur in decline phases, as these this may put at risk the economic and social future of the destination area[ix].

Environmental concerns have led to moves towards the development of sustainable tourism in recent years, particularly as a consequence of the increase in the number of tourists. Sustainable tourism may be defined as the optimal use of natural and cultural resources for national and regional development on an equitable and self-sustaining basis, providing a unique visitor experience and improving the quality of life. By contrast, others have instead considered that sustaining tourist numbers is the main objective. Whatever the case, it is clear that tourism has important economic, social and environmental implications that should not be overlooked when evaluating the impacts of the tourist industry upon a given region. Important developments in accordance with this perspective have included the definition of sustainable tourism, the use of eco-labeling (e.g. ecotourism) and the levying of tourist taxes aimed at raising the revenues required to correct the environmental damage caused.

Visitors inevitably have an impact upon such local public goods as roads, parks and recreation facilities. These may be supplied to users free of charge, and financed through income taxes. Additional use of these public goods by tourists may add to the costs, through congestion and the increase in the costs of maintenance, but tourists may not contribute to the costs of provision. This would constitute a cost imposed by additional tourism. In response, local governments worldwide are moving towards covering these costs by requiring new tourist industry developments to contribute to financing local infrastructure, thus making tourists pay (indirectly) for their use of local public goods[x].

Many of these effects are likely to be quite small in the case of countries with well-developed markets. Taxes and profits on most goods and services are not high, tariffs are moderate and declining, and supply elasticities for most tourist products are quite high, thereby limiting the potential for price increases. While externalities can be large or small and the size of employment effects is difficult to quantify, the overall net gains from additional tourism expenditures is likely to be significantly less than the total expenditure (Dwyer and Forsyth, 1993).

Additionally, the risk of some crowding-out effects is always there. Tourist booms increase local income and the demand for goods. The relative price of all non-traded goods increases, as well as the relative price of land and the relative wage rate, which renders agricultural and manufacturing activities less attractive. Greater visitor expenditure generally increases employment by firms within the tourism sector, but job losses may occur elsewhere in the economy, particularly if resources are drawn away from other export-oriented industries. This is true whenever labour substitution arises between different industries, owing to a demand for similar sets of skills that are in short supply.

4. Local or global public goods? What is the appropriate level of policy intervention?

The public goods problem highlighted by Samuelson (1954) led to Tiebouts 1956 response. While Samuelson highlighted the non-excludability of public goods and the fact that, as an important consequence, a decentralized mechanism to achieve their optimal provision cannot be found[xi], Tiebout (1956) argued that there was a class of public goods, namely local public goods, for which a decentralized mechanism for achieving optimal allocation does indeed exist. His paper, along with others published in reaction to Samuelsons article, focused on the fact that many public goods are subject to congestion. This is especially true, it was argued, of public goods provided by local governments. These are available to everyone in the community, but for any given level of infrastructure, the more people who use the facility the more crowded it becomes, and the less it is available or useful to others. In Musgraves terminology, local public goods are characterized by non-excludability but not non-rivalry; they are partially rival (or partially non-rival).

As discussed above, environmental assets have characteristics that are in some ways akin to those of local public goods, insofar as their excessive or inadequate use can lead to lesser availability for each user. In a more specific assessment, a major question arises from the fact that, in the case of activities based on environmental resources, social costs (crowding, congestion, erosion, environmental degradation, visual pollution caused by new buildings, etc.) tend to be internal to the region, while social benefits can be partially external. The example of Venice is paradigmatic of a case where the social costs are internal to the region, but social benefits are partially external [xii].

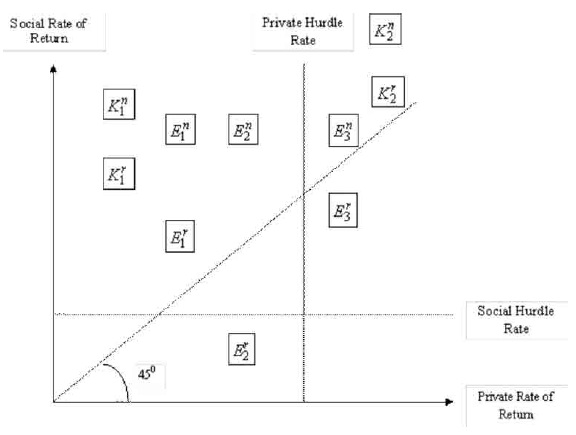

Although the answer to this problem is not an easy one, figure 1 arguably helps to address the issue of social evaluation by taking into account that there are differences between national and regional social evaluation. Innovation policy usually assumes that, in the case of typical knowledge-based investments, social benefits may exceed private benefits, but there are no negative externalities. For this reason, knowledge-based investments should always be represented above the 45º line in figure 1. In the event that the social benefits at the national level exceed those at the regional level, this does not pose a very significant dilemma: at most, the need may arise for some articulation between regional and national policies. For instance, K1 might illustrate the case of public investment in basic research, where the private return is low but social return can be very high; in this case, external benefits will spread not only inside the region but also to the outside, including internationally. Regional subsidising of this kind of investment may be sub-optimal from a national point of view, and call for some articulation with national funding. Similarly, Kn2 and K2r might represent the social evaluation, at the national and regional levels respectively, of a profitable private investment based on knowledge that generates some positive externalities at the regional level and even more of those externalities at the national level.

Fig. 1 – Private and social evaluation of projects.

Fig. 1 – Avaliação privada e social dos projectos.

As investments that make use of environmental resources can generate both positive and negative externalities, they can be represented in figure 1 both above and below the 45º line (in the latter case, the negative externalities prevail over the positive ones, and the social return is smaller than the private return). Additionally, because in this kind of investments social costs are internal to region but social benefits can spread outside, the vertical distance between the points designated by the superscripts r and n tends to be greater. For instance, E2 might illustrate the case of a national infrastructure (say, a highway) that is of great national interest but whose environmental costs at the local level are so high that the regional social evaluation is clearly negative. E1 and E3 correspond to other less dramatic but nonetheless relevant cases: both are above the social hurdle rate, but while E1 should receive support from both the regional authorities and the national ones, E3 would justify support from the national authorities and disincentive by the regional ones, due to the negative social regional assessment.

In practice, things can be even more unclear, given that the perception of social costs and benefits is far from objective and is subject to a number of social pressures. For instance, one might think that a private investment with high local environment costs (for instance, a residential and golf resort that encroaches upon a protected biodiversity area) would have a negative social evaluation at the local level but could have a positive national evaluation considering its aggregate effects upon tourism. In reality, in this kind of investments we often find the opposite: local governments seeking to authorize and support these investments, and the latter ending up blocked by regulations at the national level. This may be due to a number of reasons, which we shall briefly mention without discussing them in detail: local benefits may be perceived as immediate, while local costs may only make themselves manifest after the current local political cycle; local promoters may have lobbying capacity vis-à-vis the local authorities but not the national government; and so on.

In any case, it is clear that differences between local / regional and national social evaluations do exist and can pose major problems to innovation policies based on the valorisation of environmental resources. Overcoming this problem inevitably requires coordination between national and regional policies.

IV. POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis has focussed on the relationship between environmental resources and regional development. The term environmental resources has been used as referring to both natural and cultural resources. Specifically, it has been used to refer to non-exhaustible natural resources and tangible cultural assets. They are both partially non-rival in their use, and the fact that both must be considered from a strong sustainability perspective, insofar as human-made capital cannot substitute or make up for their destruction.

Environmental resources can play a major role in constructing regional competitive advantages and in differentiating regional development strategies. However, the specificities of environmental resources have a number of policy implications. First of all, the process of creating economic value based on the use of environmental resources must also incorporate knowledge and innovation. This is important in order to avoid the extensive use of environmental resources and the crowding-out of previously-existing or potential new activities; it also helps to ensure the sustainability of the environmental resources, in addition to generating economic opportunities for the science and technology system. Thus, while the growth of environment-based activities drawing on an extensive use of environmental resources corresponds to a comparative advantage logic based on factor endowment, environment-based innovation is typically a source of new competitive advantages.

A second general idea is that, when using environmental resources, the social costs and benefits of private investments often exceed their private costs and benefits. This calls for public intervention through a combination of taxes and incentives. While taxes should be levied in such a way as to reflect the extent of the environmental costs, incentives should be closely linked to the innovative intensity of private investments. However, the use of environmental resources has relevant policy consequences not only as far as market failures are concerned, but also in terms of the issue of coordination failures.

Addressing innovation policy from a Regional Innovation Systems perspective seems to provide an appropriate framework for managing the economic valorisation of environmental resources. Traditional innovation policy instruments had little to do with the RIS perspective: instead, the basic foundations of standard innovation policy relied on the idea that R&D activities are a source of technology spillovers[xiii]. On the empirical front, several authors have also shown the importance of the social returns to R&D[xiv]. Because the private returns to innovative activities are lesser than their social returns, governments are warranted in subsidising R&D. Governments at the national level have traditionally used direct funding of basic and applied research, as well as indirect methods such as the patent system and research tax credits, to help mitigate market failures and the resulting underinvestment problem.

From a knowledge economy perspective, the RIS concept has been inspiring regional development policies and the construction of regional competitive advantages, leading to innovation policies that are much more territorially-based than was the case in the past. Although policy priorities may differ in accordance with the different typologies of RIS, the focus is clearly on the provision of network-based support and on strengthening the regions institutional infrastructure. Because the RIS perspective emphasises innovation as a highly localised process favoured by interactions (Asheim and Gertler, 2005), policy instruments are often based on the idea of public-private partnerships (PPP) involving a variety of local actors. For instance, the provision of support to R&D and technological innovation projects promoted by firms in consortium with public entities belonging to the Science and Technology System is already a typical PPP in innovation policies. Likewise, programmes aimed at promoting the creation of technological start-ups are almost always based on institutional networks involving public agencies, universities, technology centres, research institutes, financial organizations, entrepreneurial associations and other non-profit institutions. Of course, technological PPP may also be present in national innovation policies, as described by Stiglitz and Wallsten (1999, 2000). However, the aforementioned relevance of proximity in the innovation process suggests that the effectiveness of technological PPP will often be greater at the local level or under local or regional management.

As we have discussed elsewhere (Silva and Rodrigues, 2005a and 2005b), PPPs can bring important benefits on their own, as a specific instrument for innovation policy as well as for other public policies. Compared to more traditional policy instruments, such as direct funding of public agencies and the provision of direct subsidies to firms, PPPs rely on some distinct and possibly more beneficial principles, such as (i) contractual funding, (ii) the bringing together of private and public resources and (iii) subsidiarity and decentralization. As a general instrument for public policies, the use of PPP converges with the spirit of the so-called New Public Management, and it is not hard to foresee that, in several contexts, PPP can bring more efficacy and efficiency to public policies.

When applied to innovation policy, the main argument in favour of the use of PPP is not different from the general argument for public intervention: PPP must be seen as an instrument aimed at ensuring or reinforcing the provision of relevant productive services to firms when simple market mechanisms do not afford an adequate provision of them. Consequently, the main argument in favour of technological PPP, as pointed out by Stiglitz and Wallsten (2000), is the existence of market failures linked to the positive externalities of technological activities. However, because PPP correspond, by definition, to a collaborative effort between several public and private agents, we can regard PPP as an adequate instrument for solving not only market failures but also co-ordination failures. Co-ordination malfunctions (see Hoff and Stiglitz, 2001) mean that the decisions of different agents are interdependent and that a co-ordination effort can anticipate efficiency benefits and avoid social costs[xv].

The economic use of environmental resources calls for strong coordination, namely because investments are interdependent but also because environmental resources are partially rival goods – their endowment and regeneration (or recreation) depending to a great extent on collective actions. As explained before, constructing competitive advantages and sustainable development paths based on both natural renewable resources and tangible cultural resources largely depends on the capacity to take advantage of the externalities that are associated with technical and symbolic knowledge, as well as on the increasing returns that are generated by the interdependence between different investments. In this context, and in consonance with the RIS perspective, the regional and local levels of policy implementation seem to be unavoidable, and instruments of the PPP kind seem much more effective than a simple system of taxes and subventions.

When using environmental resources, the social costs are mainly internal to the region, while the social benefits may spread to the outside. Therefore, some kind of coordination between regional / local and national policies is called for. For several reasons, which we have not discussed in detail, it remains unclear what the most appropriate way of implementing this coordination is, and it seems likely that the coordination costs are in some cases quite high.

REFERENCES

Aghion Ph, Howitt P (1992) A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2): 323-351.

Arrow K J (1962) The economic implications of learning by doing. Review of Economic Studies, 29 (3): 155-173.

Ascher W (1999) Why governments waste natural resources: policy failures in developing countries. The John Hopkins University Press.

Asheim B, Gertler (2005) The geography of innovation. In Fagerberg J, Mowery D C, Nelson R R (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, Oxford University Press, Oxford: 291-317.

Auty R M (2001) Resource abundance and economic development. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Auty R M (1994) Industrial policy reform in six large newly industrializing countries: The resource curse thesis. World Development, 22: 11-26.

Auty R M (1993) Sustaining development in mineral economies: the resource curse thesi. Routledge, London.

Barbier E (1987) The concept of sustainable economic development. Environmental Conservation, 14 (2): 101-110.

Barro R J (1997) Determinants of economic growth – a cross country empirical study. The MIT Press, Cambridge – Massachusetts.

Barro R J (1991) Economic growth in a cross section of countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106 (2): 407-443.

Becattini G (1979) Dal settore industriale al distretto industriale. Alcune considerazione sullunita dindagine delleconomia industriale. Rivista di Economia Industriale, 1: 8-32.

Besson E, Paskaleva K (2005) IT Resource Centre for the Exchange of Innovative Cultural Tourism Practices. Picture Projects, Sixth Framework Programme.

Blomstrom M, Meller P (1990) Trayectorias divergentes. Comparación de un siglo de desarrollo económico Latinoamericano y Escandinavo. Cieplan– Hachette, Santiago.

Brown G, Giles R (1994) Coping with tourism: an examination of resident responses to the social impact of tourism. In Seaton A V (ed.) Tourism: the state of the art. Wiley, Chichester: 755-764.

Buhalis D, Fletcher J (1995) Environmental impacts on tourist destinations: an economic analysis. In Coccossis H, Nijkamp P (eds.) Sustainable tourism development. Avebury, Aldershot: 3-24.

Commission of The European Communities (2006) Green paper. Towards a future maritime policy for the union: a European vision for the oceans and seas.

Commons J (1931) Institutional economics. American Economic Review, 21: 648-657.

Cooke Ph (2001) Regional innovation systems, clusters, and the knowledge economy. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10 (4): 945-974.

Cooke Ph (1998) Introduction: origins of the concept. In Braczyk H, Cooke Ph, Heidenreich M (eds.) Regional innovation systems. UCL press, London: 2-25

Cooke Ph et al. (2006) Constructing regional advantage, principles, perspectives, policies. Directorate-General for Research, European Commission.

Costanza R, Daly H E (1992) Natural capital and sustainable development. Conservation Biology 6(1): 301-311.

Dasgupta P S, Heal G M (1979) Economic theory and exhaustible resources. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Douglas-Westwood Limited (2005) Marine industries global market analysis. Marine foresight series 1, the Marine Institute, Ireland.

Dwyer L, Forsyth P (1993) Assessing the benefits and costs of inbound tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 20 (4): 751-768.

El Sarafy S (1991) The environment as capital. In Castanza R (ed.) Ecological economics: the science and management of sustainability. Columbia University Press, New York: 168-175.

Freeman Ch. (1995) The national system of innovation in historical perspective. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19 (1) 5-24.

Freeman Ch. (1987) Technology and economic performance: lessons from Japan. Pinter, London.

Garcia Mira R et al. (2003) Culture, environmental action and sustainability. Hogrefe and Huber, Göttingen.

Gillis M, Perkin H D, Roemer M, Snodgrass D R (1996) Economics of development. Norton.

Gray C, Kaufmann D (1998) Corruption and development. Finance and development, March: 7-10.

Griliches Z (1992) The search for R&D spillovers. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 94, Suplement: 29-47.

Gylfason T (2001a) Natural resources, education, and economic development. European Economic Review, 45: 847-859.

Gylfason T (2001b) Nature, power and growth. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 48(5): 558-588.

Gylfason T (2000) Resources, agriculture, and economic growth in economies in transition. Kyklos, 4: 545-580.

Harrod R (1948) Towards a dynamic economics. MacMillan, London.

Harrod R (1939) An essay in dynamic theory. Economic Journal, 49: 14-33.

Hartwick J M (1995) Constant consumption paths in open economies with exhaustible resources. Review of International Economics, 3(3): 275-283.

Hartwick J M (1978) Substitution among exhaustible resources and intergenerational equity. Review of Economic Studies, 45: 347-374.

Hartwick J M (1977) Intergenerational equity and the investing of rents from exhaustible resources. American Economic Review, 67(5): 972-974.

Hoff K, Stiglitz J (2001) Modern economic theory and development. In Meier G M, Stiglitz J E (eds.) Frontiers of development economics. Oxford University Press, New York: 389-459.

Hunter C, Green H (1995) Tourism and the environment. A sustainable relationship? Routledge, London and New York.

Jones C I (1995) R&D-based models of economic growth. Journal of Political Economy, 103 (4): 759-784.

Jones C I, Williams J C (1998) Measuring the social return in R&D. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113: 1119-1135.

Krueger A (1974) The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review, 64: 291-303.

Leite C, Weidmann J (1999) Does mother nature corrupt? Natural resources, corruption and economic growth. IMF Working Paper.

Lucas R E (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22 (1): 3-42.

Lundvall B-A (1992) National innovation systems: towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. Pinter, London.

Mauro P (1998) Corruption: causes, consequences and agenda for further research. Finance and Development, March: 11-14.

MKW (2001) Exploitation and development of the job potential in the cultural sector in the age of digitalization. DG Employment and Social Affairs.

Nassauer J I (1997) Cultural sustainability: aligning aesthetics and ecology. In Nassauer J I (ed.) Placing nature: culture and landscape ecology. Island Press, Washington DC: 275-283.

Nelson R R, Phelps P S (1966) Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 61: 69-75

Nelson R R, Rosenberg N (1993) Technical innovation and national systems. In Nelson R R (ed.) National innovation systems: a comparative analysis. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 3-21.

Neumayer E (2003) Weak versus strong sustainability: exploring the limits of two opposing paradigms (2nd ed.). Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

North D (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

OConnor J (1999) Cultural intermediaries and cultural industries. In Verwijnen J, Lehtovuori P (eds.) Creative Cities. University of Art and Design Publishing Unit, Helsinki.

ORiordan T (1988) The politics of sustainability. Belhaven Press, London.

ORiordan T, Jordan A (1995) The precautionary principle in contemporary environmental politics. Environmental Values, 4 (3): 191-212.

Pearce D W, Atkinson G D (1993) Capital theory and the measurement of sustainable development: an indicator of weak sustainability. Ecological Economics, 8: 103-108.

Pearce D W, Turner R K (1990) Economics of natural resources and the environment. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Porter M (1990) The competitive advantage of nations. The Free Press, New York.

Porter M (1998a) Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76 (6): 77-90.

Porter M (1998b) Clusters and competition: New agendas for companies, governments and institutions. In Porter M (ed.) On Competition. Harvard Business School Press, Boston: 197-287.

Ricardo D (1817) The principles of political economy and taxation. 1st Ed.; 3th Portuguese Edition, Princípios de Economia Política e de Tributação. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, 1983.

Rita P (2000) Tourism in the European Union. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12 (7): 434-436.

Rodriguez-Clare A (1996) The division of labor and economic development. Journal of Development Economics, 49: 3-32.

Rodriguez F, Sachs J D (1999) Why do resource-abundant economies grow more slowly? Journal of Economic Growth, 4: 277-303.

Rodrik D (1996) Coordination failures and government policy: a model with applications to East Asia and Eastern Europe. Journal of International Economics, 40(1-2): 1-22.

Romer P (1993) Idea gaps and object gaps in economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 32(3): 543-573.

Romer P (1990) Endogenous technical change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5): S71-S102.

Roseinstein-Rodan P N (1943) Problems of industrialization of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. The Economic Journal, 53: 202-11.

Sachs J D, Warner A M (2001) Natural resource and economic development: the curse of natural resources. European Economic Review, 45: 827-838.

Sachs J D, Warner A M (1999a) The Big Push, natural resource booms and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 59: 43-76.

Sachs J D, Warner A M (1999b) Natural resource intensity and economic growth. In Mayer J, Chambers B, Farooq A (eds.) Development policies in natural resource economics. Edward Elgar Publishing. Cheltenham.

Sachs J D, Warner A M (1995) Natural resource abundance and economic growth. http://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/5398.html NBER Working Paper 5398.

Samuelson P A (1954) The pure theory of public expenditures. Review of Economics and Statistics, 36: 387-389.

Saviotti P P (1997) Innovation systems and evolutionary theories. In Edquist C. (ed.) Systems of innovation – technologies, institutions and organizations. Pinter, London: 180-199.

Shockley G (2004) Government investment in cultural capital: a methodology for comparing direct government support for the arts in the US and the UK. Public Finance and Management,4 (1): 75-102.

Silva M R, Rodrigues H (2005a) Competitiveness and public-private partnerships: towards a more decentralised policy. Research – Work in Progress, n. 171, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto.

Silva M R, Rodrigues H (2005b) Parcerias público-privadas e eficiência empresarial colectiva. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 10: 27-50. [ Links ]

Solow R M (1986) On the intergenerational allocation of natural resources. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 88(1): 141-149.

Solow R M (1974a) The economics of resources or the resources of economics. American Economic Review, 64(2): 1-14.

Solow R M (1974b) Intergenerational equity and exhaustible resources. Review of Economic Studies, 41 (Symposium): 29-46.

Solow R M (1957) Technical change and the aggregate production function. Review of Economics and Statistics, 39 (3): 312-320.

Solow R M (1956) A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70 (1): 65-94.

Stiglitz J E, Wallsten S J (1999) Public-private technology partnerships: Promises and pitfalls. American Behavioral Scientist, 43 (1): 52-73.

Stiglitz J E, Wallsten S J (2000) Public-private technology partnerships. In Rosenau P. (ed.) Publicprivate policy partnerships. The MIT Press, Cambridge: 37-58.

Tiebout C M (1956) A pure theory of local expenditures. Journal of Political Economy, 64: 416-424.

Tisdell C A (1987) Tourism, the environment and profit. Economic Analysis & Policy, 17(1): 13-30.

Tisdell C A (1983) Conserving living resources in Third World countries: economic and social issues. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 22: 11-24.

Throsby D (2003) Cultural Capital. In Towse R (ed.) A handbook of cultural economics. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham: 166-169.

Throsby D (1999) Cultural capital. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23(1-2): 3-12.

Throsby D (1997) Sustainability and culture: Some theoretical issues. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 4: 7-20.

Torvik R (2002) Natural resources, rent seeking and welfare. Journal of Development Economics, 67: 455-470.

Victor P A (1991) Indicators of sustainable development: some lessons from capital theory. Ecological Economics, 4: 191-213.

WCCD (1995) Our creative diversity. World Commission on Culture and Development, UNESCO, Paris.

WCED (1987) Our common future. World Commission on Environment and Development, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Wright G (1990) The origins of American industrial success, 1879-1940. American Economic Review, 80 (4): 651–68.

NOTES

[ii] For a synthetic discussion of the relationship between natural resources and economics see Pearce and Turner (1990, part I).

[iii] For other earlier influential works, see Barbier (1987) on the concept of sustainable economic development and ORiordan (1988) on the politics of sustainability.

[iv] This Commission is also known as the Péres de Cuéllar Commission.

[v] Overall, the issue of specifying a sustainable development path involves the well-known debate around whether the intergenerational aspects of sustainable development are a matter of efficiency in terms of inter-temporal resource allocation, or whether they are a matter of fairness or equity in terms of the present generations treatment of its successors. It might be added that the consideration of cultural value as an additional element in the picture does not change the basic propositions at stake. The preservation of cultural resources for the benefit of future generations can be just as much a question of efficiency or equity in the allocation of resources that produce cultural benefits as it is in the case of economic returns.

[vi] As regards the issue of the sustainability of natural resources, there are two standard divergent positions: on the one hand, Dasgupta and Heal (1979), who represent a strictly neoclassical approach, and, on the other, Pearce and Turner (1990), who support the non-substitutability argument. A summary of this debate is provided in Victor (1991).

[vii] An indicator of weak sustainability is provided in Pearce and Atkinson (1993).

[viii] The term resource curse thesis was first used by Auty (1993) to describe how countries rich in natural resources were not able to use that wealth to boost their economies and how, counterintuitively, these countries exhibited lower economic growth than countries without an abundance of natural resources. See also Auty (1994; 2001).

[ix] An example of tourism decline due to environmental degradation caused by tourism is Lake Balaton in Hungary, which has traditionally been used for fishing (Hunter and Green, 1995). Increasing water pollution due to tourism has caused a decline in fishing, which in turn has led to a downturn in visitor numbers.

[x] Tourism has been shown to have significant impacts on the environment through a number of different pathways. Economic instruments such as tourist eco-charges constitute one possible way of addressing the negative aspects of tourism, both through changing behaviour and by providing funds for environmental improvement. Such charges have been applied in a number of countries, including the Balearic Islands, Bhutan and Dominica.

[xi] That is, it is not generally possible to find a way to get individuals to reveal their true valuation for public goods.

[xii] Venices worldwide fame is due, among other things, to its well-preserved architecture, St Marks Plaza, its museums, its romantic atmosphere, the gondolas, the Carnival and the Biennale of Arts. The fact that too many people visit Venice (on peak days, around 200,000 visitors) endangers its long-term preservation. Moreover, because the island is so small, this leads to competition between visitors and residents for the use of public space. Unfortunately, the main prevalent type of tourism (excursionists or people who lodge in the suburbs) means that the town loses out on many of the the possible or expected benefits of tourism. The identification of the appropriate carrying capacity of a town like Venice, where many tourists come just to soak in the atmosphere, has proven difficult and must of necessity take into account socioeconomic factors, rather than just the number of people who visit the attractions.

[xiii] Thus, Arrow (1962) argued that any new technological knowledge gives rise to positive spillovers; more recently, the idea that knowledge has the attributes of non-rivalry and dynamic feedback has gained widespread acceptance (Romer, 1990 and 1993; Jones, 1995).

[xiv] See Griliches (1992) and Jones and Williams (1998).

[xv] The argument of coordination failures as support to development policies is not a new one. The Big Push theory formulated by Rosenstein-Rodan (1943) can be considered an earlier illustration. The need of a coordinated Big Push is based on the idea that moving out of a low-level steady state requires co-ordinated and simultaneous investments in a number of different areas. The precise mechanism that generates profit functions of this form depends on the model in question. Murphy et al. (1989) develops models in which the complementarity arises from demand spillovers across final goods produced under scale economies or from bulky infrastructure investments. Rodriguez-Clare (1996), and Rodrik (1996) present models in which the effect operates through vertical industry relationships and specialised intermediate inputs.

Recebido: 10/10/2008. Revisto: 06/01/2009. Aceite: 12/01/2009.