Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

versão impressa ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.92 Lisboa dez. 2011

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

Revolutionary landscapes: the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area

Paisagens revolucionárias: as pinturas murais do PCTP/MRPP na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa

Paysages revolutionnaires: les peintures murales du PCTP/MRPP dans la zone Metropolitaine de Lisbonne

André Carmo1

1 Researcher, CEG-IGOT-ULisboa. E-mail: carmo@campus.ul.pt

ABSTRACT

This article investigates the mural paintings made by the PCTP/MRPP in the Lisbon Metropolitan area, in the aftermath of the 1974 Portuguese revolution. Drawing on Erwin Panofsky’s iconographic method of interpretation, murals are explored from an integrated landscape approach that combines two perspectives: landscapes as representations and landscapes as material artifacts. Findings suggest that the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings translated the visual ideology of social transformation and revolution underlying its politics. Furthermore, they also crystallized performative revolutionary landscapes, in the sense that they materialized acts of collective artistic citizenship, in which the social space of mural production played a fundamental role.

Keywords: PCTP/MRPP, landscape, mural paintings, iconography, representation, material artifact.

RESUMO

Este artigo investiga as pinturas murais feitas pelo PCTP/MRPP na Área Metropolitana de Lisboa, no rescaldo da revolução de 1974. Com base no método iconográfico de interpretação de Erwin Panofsky, os murais são explorados a partir de uma abordagem integrada que combina duas perspectivas: paisagens enquanto representações e paisagens enquanto artefactos materiais. Os resultados sugerem que as pinturas murais do PCTP/MRPP traduziram a ideologia visual de transformação social e revolução subjacente à sua política. Para além disso, também cristalizaram paisagens revolucionárias performativas dado que materializaram actos colectivos de cidadania artística, nos quais o espaço social da produção de murais desempenhou um papel fundamental.

Palavras-chave: PCTP/MRPP, paisagem, pinturas murais, iconografia, representação, artefacto material.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article porte sur l’étude des peintures murales du parti PCTP/MRPP qui ont été réalisées dans la Zone Métropolitaine de Lisbonne après la révolution de 1974. L’examen de ces peintures murales se base sur la méthode d’analyse iconographique D’Erwin Panofsky, à savoir une approche intégrée du paysage qui combine deux perspectives complémentaires : le paysage en tant que représentation et le paysage en tant qu’artefact matériel. Au vu des résultats, il semble que les peintures murales du PCTP/MRPP ont traduit l’idéologie visuelle de transformation sociale et de révolution sous-jacente à la pratique politique du parti. En outre, elles ont cristallisé des paysages révolutionnaires performatifs, dans le sens où elles ont constitué des actes collectifs de citoyenneté artistique dans lesquels l’espace social de la production de peintures murales a joué un rôle fondamental.

Mots-clés: PCTP/MRPP, paysage, peintures murales, iconographie, représentation, artefact matériel.

I. INTRODUCTION

Landscape is undoubtedly one of the most contested and ambiguous concepts in geography. Although it is at the core of the discipline, geographers have no monopoly over it and fields such as art history, archeology, anthropology, literary studies, sociology, architecture, and planning have also been interested in studying landscape (Aston, 1985; Hirsch and O’Hanlon, 1995; Andrews, 1999; Harvey and Fieldhouse, 2005; Kienast et al., 2007). from within the rather flexible and porous boundaries surrounding human geography as an independent field of knowledge, landscape research, mainly conducted by cultural geographers, has varied a lot, not only in what regards the meaning of the concept but also concerning the methodological approaches used to deal with it (Matless, 2003; Swaffield, 2005; Dubow, 2009).

This article investigates the mural paintings made by the PCTP/MRPP2 in the Lisbon Metropolitan area, in aftermath of the 1974 Portuguese revolution. The PCTP/MRPP mural paintings are studied from an integrated landscape approach, simultaneously seeking to describe and interpret the representations depicted and to understand the material processes associated to their production.

Although a project entitled Memories of the Far-Left in Portugal: the MRPP (1970-1976)3 is currently being undertaken, research about Portuguese radical left movements and political organizations like the PCTP/MRPP is scarce (see Cardina, 2009, 2010). On the other hand, as Godinho (2011) recently suggested, historical revision tends to relativize or recover authoritarian historical periods while, at the same time, condoning the moments when the disempowered and subaltern fringes of society managed to get some prominence. In the Portuguese case this means that the revolutionary period is either seen as an insignificant phenomenon or as an antidemocratic threat to the democratic society that eventually emerged, thus becoming historically neutralized. By looking at the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings, this article simultaneously contributes to the field of research about radical left movements and political organizations, to the reconstruction of a positive social imaginary of revolutionary periods, and to landscape studies from the perspective of cultural and political geographies. This article is divided in three main parts. It starts out by presenting the theoretical rationale and the methodological approach used in this research. This is followed by a brief historical contextualization of the PCTP/MRPP emergence and a detailed examination of its mural paintings. Finally, a discussion of the main findings is presented as well as some concluding remarks.

II. UNDERSTANDING LANDSCAPES

1. Integrated landscape approach: representations and material artifacts

Despite the variety of possibilities for landscape as a field of inquiry pointed out by Gaspar (2001) a decade ago, it seems possible to identity two broad perspectives that have been used to investigate it. One primarily concerned with landscape as representation, the other, focused on landscape as material artifact. Our goal is not to extensively review the literature (Jackson, 1984; Olwig, 1996; Salgueiro, 2001; Wylie, 2007), but to briefly point out slightly different understandings within those perspectives, thus mapping the theoretical rationale for this research.

The perspective of landscape as representation emphasizes its aesthetic, representational and symbolic aspects, the form, content and meanings it acquires, and how they combine giving shape to a particular landscape. in its contemporary formulation, this perspective initially started being developed in the 1980s due to an increasing convergence between geography and the humanities (Daniels, 2004). For Cosgrove (1984, 1985, 1989) landscape was conceived as a way of seeing the world, i.e. as a visual construction, a pictorial symbolic composition reflecting a specific set of values and ideas (i.e. visual ideology). The centrality of the visual for this understanding came from the fact that there is no universal way of seeing and that power relations influence representations. Therefore, landscape becomes a crucial element for the construction of geographical imaginations (Cosgrove, 1994, 2001, 2008). In his own work Daniels (1989, 1993) also highlighted the centrality of the visual. In fact, both were responsible for editing The iconography of landscape (1988), a landmark collection of essays from this perspective.

Duncan (1990), Duncan and Duncan (1988, 2003), Duncan and Ley (1993), and Barnes and Duncan (1992), have privileged a landscape-as-text understanding. In this sense landscape is conceived as a symbolic form to which unstable meanings and interpretations are ascribed. Furthermore, being influenced by post-structural theories, this understanding is also attentive to matters of readership and authorship, as they are constitutive of signification processes that are intrinsically multi-layered, dynamic, and complex. As a result, landscape is understood as an inter-textual representation made of a dense fabric of interconnected meanings immersed in broader sociocultural contexts.

This path has been further explored by W. J. T. Mitchell (1994, 1996), who sought to change landscape from a noun to a verb, asking us to think about landscape not as an object to be seen or text to be read but as a process by which social and subjective identities are formed. Thus, he looked at landscape as a dynamic cultural practice and medium of dialogical communication with the potential to disrupt power relations and able to challenge the existing social order. The complex connection between landscape and identity has also been underlined by Bender (1993: 3) who has written that ‘the landscape is never inert, people engage with it, re-work it, appropriate and contest it. it is part of the way in which identities are created and disputed, whether as individual, group, or nation-state’.

The perspective of landscape as material artifact re-orientates the discussion towards the intrinsic materiality at the core of the social relations responsible for landscape production. Arguably an important scholar working from within the Marxist tradition, Don Mitchell (1994, 1996, 2002, 2003), has systematically noted that the continuing relevance of landscape has to do with the social power it entails. Landscape, as Harvey (1996: 79) suggested, ‘instantiate and objectify human desires in the material world, not only through reproduction of self and bodily being but also through modifications of surrounding environments’. Thus, the study of landscape requires a particular attention to the concrete material processes and socio-spatial relations through which it is produced. the abandonment of the material world in order to focus almost exclusively on the politics of reading, language and hermeneutic interpretations represents a dangerous politics as it only tells half the story, i.e. how landscape is consumed (Olwig, 2005). it falls prey to what Peet (1996) has called idealist-representative relativism, as it fails to acknowledge that a landscape is not a text per se but rather a material form that, among other things, also has textual qualities. as Don Mitchell (2005: 54) has written: ‘to see the power at work in the landscape requires attention not just to the landscape (as a form, representation and set of meanings) in and of itself, but to the social relations that give rise to and make possible the landscape’s ability to do work’.

Within this perspective, a rather different understanding has been developed by scholars such as Dewsbury et al. (2002), Harrison (2007), Latham (2003), Lorimer (2005, 2007, 2008), Nash (2000), Rose and Wylie (2006), Smith (2003), and Thrift (1996, 1997, 2007), who have been influenced by non-representational theorists (e.g. Haraway, Latour, Deleuze, Bahktin, Merleau-Ponty). From our point of view, the work made by these scholars is important as it is focused on performativity and the embodiment experiences associated to landscape production. In other words, it looks at landscape as a material form emerging during procedural and transformative practices (ways of doing and/or becoming) that are necessarily embodied. Thus, landscape can take the shape of specific moments or particular events that, despite being geographically circumscribed and often ephemeral, can produce relevant socio-spatial effects.

In sum, the former perspective is based on three main understandings, namely, the relations between landscape and visual ideology, matters of authorship and the way landscape is interwoven with processes of identity formation. The latter is focused on two main understandings, namely, the relevance ascribed to the social space of landscape production, and the performative and embodied nature of landscape production. Together, they provide the basis for our discussion of the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings from an integrated landscape approach.

2. Erwin Panofsky’s iconographic method of interpretation

Having no specific tools for investigating visual representations, geography can turn to Erwin Panofsky (1892-1968), the German art historian who originally devised iconography as method for visual interpretation (Mitchell, 1986; summers, 1995; Leeuwen, 2001; Howells, 2003). In its initial formulation, iconography was conceived as the ‘branch of the history of art which concerns itself with the subject matter or meaning of works of art, as opposed to their form’ (Panofsky, 1972: 3). As an iconographic system of interpretation, it was based on a multi-layered and contextualized approach to representations, overlapping with our own knowledge of the world, in the sense that the latter comes out of a process of apprehension that unfolds over time (Preziosi, 2009). Hence, art works were conceptually organized according to three constitutive layers of meaning. Each one of them intrinsically connected to all the others, allowing one to map the general structure of a specific cultural artifact (Hoelscher, 2009).

in his seminal work – Studies in Iconology (1972) – Panofsky described the three levels of examination entailed by the method he devised. The most superficial level corresponds to the first level of visual interpretation (pre-iconographic) and, as it is concerned with the identification of what is depicted in the image, it is primarily based on a clear observation and description of its contents. The second level (iconographic) is underlined by the notion that what is depicted means something else, thus emphasizing the symbolic value of the images depicted. Finally, the third level (iconology) is both deepest and broader, requiring the interpretation of the contextual social fabric from which representations emerge. As a whole, this tripartite iconographic system of inquiry can be acknowledged as a ‘method of interpretation which arises from synthesis rather than analysis’ (Panofsky, 1970: 32).

Due to the fact that this method has a multi-layered structure entailing two levels especially concerned with landscape as representation but also a third level that is focused on landscape as material artifact, it seems to provide a coherent instrument to address the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings from an integrated landscape approach.

For this research, mural painting images (photographs and slides) were collected from two main sources: the PCTP/MRPP and an anonymous personal archive. In both cases, the information available had significant lacunae concerning basic descriptive characteristics such as year of production, location, and authorship. Regarding landscape as representation, a collection of nearly 20 mural painting images was used to produce an extensive interpretation. At the same time, two mural paintings were examined in-depth, according to the perspective of landscape as material artifact. In addition, 34 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted during a two month period, allowing some of the arguments put forth to be further explored, in a more vivid fashion, by those that had firsthand experience of them.

III. THE PCTP/MRPP MURAL PAINTINGS

1. The origins of the PCTP/MRPP and its mural paintings

The MRPP4 was clandestinely founded on the 18th of September 1970 in a political atmosphere of great complexity (Feio et al., 1975; Balso, 1976; Cordeiro, 2009). At the national level, the active resistance to Salazar’s fascist regime became progressively stronger during the 1960s. The end of the decade witnessed the emergence of Portuguese universities as particularly fertile grounds for the development of radical political organizations (Ventura, 1993). Internationally, the Portuguese ‘African empire’ was already crumbling. it faced severe resistance from African nationalist organizations such as the PAIGC in Guinea and Cape Verde, the FRELIMO in Mozambique, and the MPLA in Angola, and in response the Portuguese state started a war that would last more than a decade (1961-1974) (Mailer, 1977).

The origins of the MRPP were somewhat related to the PCP positions regarding the CPsU5 (Martins and Loureiro, 1980) and the colonial war (Cardoso, 2011). Together, they paved the way to the emergence of a significant number of radical organizations. The MRPP developed from an organization called EDE (Democratic Student Left), whose activity was closely associated with the faculty of Law of the Lisbon University. Before 1974 there were several anti-colonial organizations connected to the MRPP, namely, the RPAC (Popular anti-colonial resistance), the CLAC (anti-colonial struggle Committee) and the MPAC (Anti-Colonial Popular Movement), constituting an alternative to the PCP position towards the colonial war. In addition, the MRPP also had a student organization called FEML (Marxist- -Leninist student federation). At the time there was already an intense editorial work being carried out and it started publishing its journal – Luta Popular – in 1971. Public demonstrations were also conducted by the MRPP on a regular basis and it was also in this period that the first mural paintings were produced. However, due to the political repression, most paintings consisted merely of rapidly scribbled subversive political sayings waged against the fascist regime.

After the 25th of April, 1974, the MRPP faced turbulent years, both outside and inside the movement, as the ‘red/black’6 debate and the imprisonment of 432 militants by the COPCON (28th of May, 1976) illustrate but, in December 1976, the PCTP/ MRPP was officially founded. By then elaborated mural paintings were already being made, inspired by other revolutionary muralist traditions such as the Mexican and the Chinese ones. The new atmosphere of political freedom and social experimentation paved the way for revolutionary political messages to be inscribed in visible and accessible public spaces. Nevertheless, by the end of the 1970s, the PCTP/MRPP was struggling with severe financial and organizational problems and, as a result, its mural paintings production declined.

2. The PCTP/MRPP mural paintings as representations

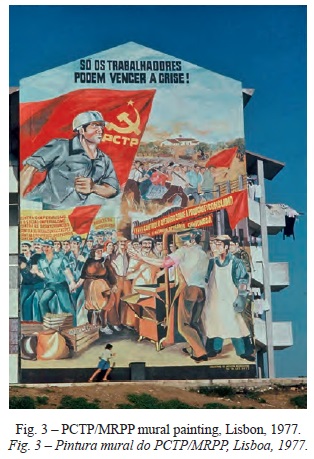

Table I displays a synthesis of the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings as representations based on a comparative extensive examination. Often, murals presented a mixed content, meaning that the elements depicted did not represent isolated actions or events, but rather a series of scenes organized as a socio-political narrative. Usually they displayed locations within or in the surrounding areas of factories, farms, streets and other settings. Thus, the idea of public spaces as the places where politics and acts of citizenship occur is embedded in the narratives depicted (Isin and Nielsen, 2008). Up to a certain extent this was what interviewee n77 suggested when he said that the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings where descriptive murals of the people, the workers in the factories, soldiers and people on the streets where everything happened.

Mural painting representations highlighted significant events happening in the 1970s, such as presidential elections, the overt antagonisms and conflicts existing between different political organizations and movements, and other significant events occurring at the time. interviewee n308 sought to describe the relationship established between the PCTP/MRPP, Portuguese politics and the production of mural paintings noting that in a specific moment of the national life, current politics were discussed at the Central Committee level and then went all the way down until reaching the graphic committee (…) after defining the political guidelines to apply in the paintings they were discussed in the graphics committee and the propaganda department.

In general, murals displayed two interrelated moments: first, the popular struggle against the status quo in its various configurations, generally targeting the consolidated power structures that managed to emerge in the aftermath of the Portuguese revolution; second, an effort was frequently made to gather popular support for the positions defended and expressed by the PCTP/MRPP. Political propaganda usually took the form of an appeal for voting in the candidates supported by the party.

According to Taylor (1981), color is also a fundamental aspect of mural painting representations iconography. Three parameters are considered particularly relevant: hue (i.e. colors present in mural paintings), saturation (i.e. the relative purity of hues in comparison to their appearance in the spectrum), and value (i.e. the relative lightness or darkness of the colors used). As for hue, in the PCTP/MRPP case, it consisted mainly of yellow, red and black. The first two, also the main colors of the PCTP/MRPP symbology, were usually used to fill the backgrounds, to frame the mural painting, or to color the PCTP/MRPP flags when they were used. Black paint tended to be used to outline figures and volumes, its usage decreased as the degree of complexity of mural paintings increased. As for saturation, it was very high in the PCTP/MRPP paintings as colors tended to be used in a quite vivid manner. By the same token, value was also high because colors were usually closer to the brighter side of the color spectrum. As a whole, the importance of the colors used for the general impact of the mural paintings was highlighted by interviewee n109 who claimed that the impact still remains today and people still remember. The mural painting, not only by its quality, for the colors chosen, the yellow and the red, and also the message, the strength transmitted (…) the truth is that our paintings always had a huge impact among the others, more or less strange and confusing, made by the great painters of the PCP.

Looking at the spatial organization of the representations depicted in mural paintings requires us to pay attention to two parameters. In terms of the internal spatial organization of the representations they featured a linear dynamic arrangement, meaning that the volumes depicted followed rather rigid linear directions. Simultaneously, a sense of rhythm was also offered to the mural painting observers. rather than being static, representations were displayed in a dynamic manner, almost as if the different contents and figures were in motion. Concerning their external spatial organization, mural representations presented two main features, namely, linear perspective and spatial distortion. The former, meaning that the arrangement of volumes and figures was based on the relative diminution of their apparent size according to the distance separating them from the observer’s point of view. The latter, meaning that in some representations the middle distance was ignored, or at least diminished, thus contributing to create a sense of space and grandeur (Acton, 1997). Moreover, two different kinds of light were primarily used in the PCTP/MRPP mural painting representations: daylight, to create a sense of space, further contributing to widen the landscape horizons; and firelight, attempting to increase the dramatic intensity of the representations portrayed.

Finally, the expressive content of mural representations, i.e. the feelings and reactions the mural painting created in the observers. Due to the fact that the interpretation of such a subjective matter relies heavily on the position of the observer, it seems better to give voice to interviewee n210 who recalled that mural paintings contributed for the party’s impact in society, both at the political and aesthetic levels. One looks at a PCTP/MRPP mural, sees and feels what is depicted. It is not necessary to have someone explaining what it is because the images convey a clear message. Tentatively it can be argued that the expressive content of the PCTP/MRPP mural painting representations was somewhat filled with a sense of popular strength and courage. By the same token, cooperation under the guidance of a vanguard leadership was also depicted. Often leadership was left to a figure representing the PCTP/MRPP carrying a flag and adopting a predominant position within the representation.

3. PCTP/MRPP mural paintings as material artifacts

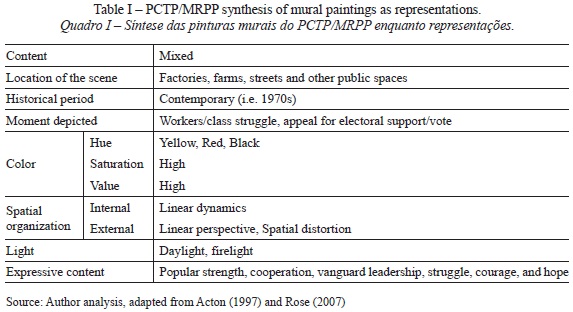

From the perspective of landscape as material artifact, the first mural painting under examination was made in one of the walls surrounding the ist11 in 1976 (fig. 1).

Three main features seem to be particularly relevant in terms of the social power associated to this particular mural painting. Firstly, it was a call to vote for Ramalho Eanes who, from the PCTP/MRPP perspective, represented a democratic position of compromise regarding the other possible candidates. Above all, it emphasized the possibility of electing a candidate other than two of the PCTP/MRPP main political adversaries, namely, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho (former leader of the COP-CON) and the PCP’s candidate (Octávio Pato). In this sense, this mural painting was conceived as an instrument of political propaganda.

Moreover, the potential political function of the mural was not dissociated from its location. The fact that it was made on the ist walls was not unintended. In fact, it was aimed at gathering support from the its students. As was mentioned earlier, the PCTP/MRPP base of support was partially constituted by the politically active youth enrolled in universities and secondary education schools of Lisbon. This mural pain ting sought to explore that condition, as the ist was one of the largest universities in the city. As the PCTP/MRPP main sources of recruitment were the faculty of Law and the faculty of arts, this location contributed for the possible expansion of its political influence to other institutional settings. Obviously, this depended on the capacity of the artists and all those involved in the production of the mural to somehow communicate the political message of the PCTP/MRPP to those passing by in a meaningful way.

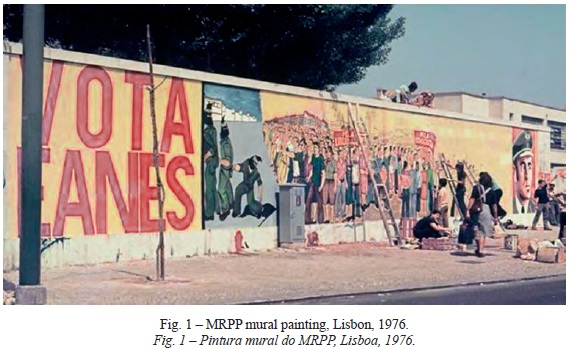

Finally, the production of this mural painting had to face great animosity from other radical leftist organizations, above all the UDP12. The conflicts and tensions between both organizations were strongly connected to the circumstances surrounding the death of Alexandrino de Sousa (MRPP militant). The MRPP blamed UDP militants for that tragic event and, from then onwards, violence became one of the trademarks of the relations between the UDP and the MRPP. in this case, both the mural painting and the artists were victims of several attacks, causing the completion of the painting to take longer than was originally expected. in addition to these, and although it was one of the first mural paintings to be subject to previous planning, there were some spontaneous and unintended public interventions contributing for it to become a performative political event. For instance, some of the people passing by requested to be depicted in the mural painting and, consequently, some of the human figures represented were real people who had to pose for the muralists (fig. 2).

As retribution, some of them stayed near the mural painting in order to help protecting it as well as the painters, from the aforementioned attacks. N7 recalled this event saying that the artists painted the people walking by, establishing dialogues, turning the moment into a collective work, in the sense that there was a strong interrelation between artists and people. Hence, the social construction of this mural painting, expanded beyond the PCTP/MRPP artists and militants, encompassing people who intentionally wanted to become inscribed in a material artifact that was simultaneously artistic and political.

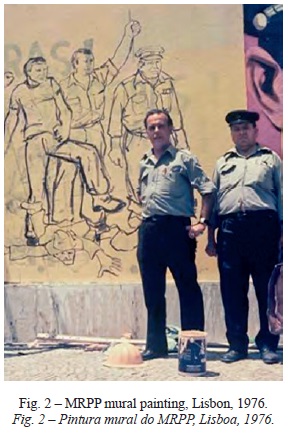

The second mural painting was made in Cabo Ruivo, a working class neighborhood on the outskirts of Lisbon, in 1977 (fig. 3). Unlike the previous one, the political purpose of this mural painting was not to make an appeal for some kind of support or participation in political processes such as voting. Instead, its goal as instrument of propaganda was broader, as it depicted a series of popular demands in line with the political ideology underlying the PCTP/MRPP.

Whereas the previous mural painting became a performative political event in the sense that it was open to a wider participatory audience, this one was produced in a much less informal way. When the preliminary ideas for this mural painting emerged, there was already a ‘graphic committee’ in charge of the whole process of mural production. The creation of the committee signals the growing importance that the PCTP/MRPP ascribed to its mural paintings as an artistic way of political engagement. Likewise, it also marked a turning point concerning the organization of the whole process of mural production. it was now becoming more and more an activity that was subject to an intense process of internal discussion before moving on to the public spaces where it was materialized.

In this case, particular attention was paid to the uniforms and clothes used by different working class sectors and the representation was strictly based on the preliminary sketch that was drawn by the committee. Nevertheless, some degree of popular participation was allowed. The mural painting was completed in a four day period. Before it started, there was an intense process of discussion with one of the residents (who was a militant of the PCP) of the building that was intended to be used as ‘canvas’, as he did not want the mural painting to be made. it was necessary to engage in a discussion partially recalled by interviewee n2413 who said that it was only after several discussions with him that we were able to explain the importance of making that mural painting in that particular place. Although reluctantly, in the end he accepted, and we were able to go ahead with our work (…) it ended up as being the most amazing mural painting ever made by the PCTP/MRPP.

Finally, as the aforementioned statement also suggests, the mural painting location was considered to be highly relevant. the fact that is was painted in a working class neighborhood, located in what came to be known as the northern industrial ribbon of Lisbon, indicates that the PCTP/MRPP was also interested in further reaching its other source of militancy, i.e. politically conscious young working class activists. Location seems to have emerged as a fundamental condition for the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings production. Thus, the potential impact of mural paintings as political and artistic material artifacts was seen by the PCTP/MRPP as being related to the social spaces where they were made.

IV. THE PCTP/MRPP REVOLUTIONARY LANDSCAPES

The study of the PCPT/MRPP mural paintings through an integrated landscape approach raises a number of issues that seem particularly relevant in order to better understand their social and political relevance. In the sense that revolutionary mural paintings convey an explicit political message that is seen as a priority in relation to the aesthetic qualities of murals, art is subordinated to politics (Sluka, 1996; Cockroft et al., 1998; Cooper, 2003; Rolston, 2004). In the PCTP/MRPP case, although there was an increasing concern with the aesthetic qualities of mural paintings, the main goal was to take the political message of the party to public spaces in order to enhance the propaganda effect, its main political function. in reality, from the perspective of landscape as representation, it can be argued that the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings expressed a visual ideology of social transformation, as they depicted narratives underlined by what Coelho (2004: 22) called a ‘movement of emancipation and an idea of revolution’. either by appealing to conventional forms of citizenship such as voting or to more revolutionary political actions anchored on popular struggles, ideas of social transformation and revolution were translated into the mural paintings, thus contributing to the PCTP/MRPP process of identity formation.

As a whole, mural painting representations sought to convey specific meanings in line with the PCTP/MRPP underlying ideology. the fact that representations privileged mixed content in the form of narratives instead of simpler contents, that they presented a spatial organization intended to express movement and dynamism, that public spaces associated to the working classes assumed a central position in compositions, that they sought to capture the political atmosphere surrounding the period in which mural paintings were made, that the moments displayed presented a tension between revolutionary and conventional politics, and that their expressive content stressed the vanguard role of the PCTP/MRPP leading the working classes, all seem to point out the correspondence between mural painting representations and the PCTP/MRPP ideology.

From the perspective of landscape as material artifact two aspects emerged as being of utmost importance for the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings production. On the one hand, location, the social space of mural paintings, is deeply connected to their processes of production. Usually, instead of being created with the aim of being placed or exposed in conventional settings (e.g. museums, showrooms), revolutionary mural paintings are conceived specifically as outdoor material artifacts. Additionally, they are predominantly connected to working-class and deprived minority neighborhoods, thus seeking to become empowering expressions of public art. The PCTP/MRPP murals followed this trend, as the two mural paintings examined in depth demonstrate. Whereas one was made near a higher education institution, the other was located in a working-class neighborhood. Thus, the spatial concentration of specific social groups to which the PCTP/MRPP was directly linked, namely, young industrial workers and students, was a matter of concern.

On the other hand, mural paintings often have a collective nature, necessarily associated to the active involvement of nonprofessional artists responsible for their design and execution. The performative nature of the PCTP/MRPP murals production serves to attest this argument as it, although to a variable degree, involved more people than those responsible for its initial planning. In this sense, they became ‘a vehicle of connection, a means to realize and recognize the commons, a medium for people to gather together to reflect on the very idea of being together’ (Martin, 2006: 4). Thus, the PCTP/MRPP murals also worked as points of departure for critical political engagement and reflection from those embodying the experience.

V. CONCLUSIONS

In this article we have sought to examine the mural paintings made by the PCTP/MRPP in the aftermath of the 1974 Portuguese revolution. In order to do that, mural paintings were investigated from an integrated landscape approach. Two broad perspectives were brought together under this theoretical framework: landscape as representation and landscape as material artifact. together they comprise understandings as varied as those focusing on the visual ideologies of landscape, matters of authorship and its role in processes of identity formation, as well as the social relations associated to its production and its embodied and performative nature.

Based on Erwin Panofsky’s iconographic method of interpretation an extensive comparison of nearly 20 mural paintings was conducted in order to examine them as representations, in parallel with an examination of two mural paintings from the perspective of mural paintings as material artifacts. Findings suggest that regarding the former, the PCTP/MRPP mural paintings translated the visual ideology of social transformation and revolution underlying its politics, thus contributing for its process of identity formation. As for the latter, they crystallized performative revolutionary landscapes, in the sense that they materialized acts of collective artistic citizenship, in which the social space of mural painting production played a fundamental role.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank Matthew Gandy for supervising the research leading up to this article, the PCTP/MRPP and an anonymous collaborator for allowing access to archives. Three reviewers and a colleague provided extremely useful and constructive comments.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acton M (1997) Learning to look at paintings. Routledge, Abingdon. [ Links ]

Andrews M (1999) Landscape and Western Art. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Aston M (1985) Interpreting the landscape. Landscape archaeology and local history. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Balso J (1976) O M.R.P.P. Tradução de J. Silva Cornélio, Edições Delfos, Lisboa. [ Links ]

Barnes T, Duncan J (eds.) (1992) Writing worlds. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Bender B (1993) Landscape – meaning and action. In Bender B (ed.) Landscape Politics and Perspectives. Berg, New York: 1-17. [ Links ]

Cardina M (2010) A esquerda radical. Angelus Novus, Coimbra. [ Links ]

Cardina M (2009) O maoísmo em Portugal: 1964-1974. In Política Operária (org.) Lutas Velhas, Futuro Novo. Dinossauro, Lisboa: 33-72. [ Links ]

Cardoso A M (2011) Um tempo, um contexto. In Rodrigues A (2011) Gente comum. Uma história na PIDE. 100LUZ, Loulé: 45-56. [ Links ]

Cockroft E, Weber J, Cockroft J (1998 [1977]) Towards a people’s art: the contemporary mural movement. University of Mexico Press, Albuquerque. [ Links ]

Coelho E P (2004) O fio da modernidade. Editorial Notícias, Cruz Quebrada. [ Links ]

Cooper D (2003) Art. In Cull N, Culbert D, Welch D (eds.) Propaganda and mass persuasion: a historical encyclopedia, 1500 to the present. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara: 21-23. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (2008) Geography & Vision: Seeing, Imagining and Representing the World. I.B. Tauris, London. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (2001) Apollo’s Eye: A Cartographic Genealogy of the Earth in the Western Imagination. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (1994) Contested global visions: one world, whole-earth and the Apollo space photographs. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 84(2): 270-294. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (1989) Geography is everywhere: culture and symbolism in human landscapes. In Gregory D, Walford R (eds.) Horizons in Human Geography. Macmillan, London: 118-135. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (1985) Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 10(1): 45-62. [ Links ]

Cosgrove D (1984) Social formation and symbolic landscape. The University of Wisconsin Press, Wisconsin. [ Links ]

Daniels S (2004) Landscape and art. In Duncan J, Johnson N, Schein R (eds.) A companion to cultural geography. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford: 430-446. [ Links ]

Daniels S (1993) Fields of vision: landscape imagery and national identity in England and the United States. Princeton University Press, Princeton. [ Links ]

Daniels S (1989) Marxism, culture, and the duplicity of landscape. In Peet R, Thrift N (eds.) New Models in Geography, Volume 2. Unwin Hyman, London: 196-220. [ Links ]

Dewsbury J, Harrison P, Rose M, Wylie J (2002) Enacting geographies. Geoforum, 33: 437-440. [ Links ]

Dubow J (2009) Landscape. In Kitchin R, Thrift N (eds.) International encyclopedia of human geography. Elsevier, Amsterdam: 124-131. [ Links ]

Duncan J (1990) The city as text: the politics of landscape interpretation in the Kandyan Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Duncan J, Duncan N (2003) Landscapes of privilege: the politics of the aesthetic in suburban America. Routledge, New York. [ Links ]

Duncan J, Duncan N (1988) (Re)reading the landscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 6: 117-126. [ Links ]

Duncan J, Ley D (1993) Place/Representation/Culture. Routledge, London. [ Links ]

Feio J, Leitão F, Pina C (1975) MRPP: O que é?Agência Portuguesa de Revistas, Lisboa. [ Links ]

Gaspar J (2001) O Retorno da paisagem à Geografia. Apontamentos místicos. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XXXVI(72): 83-99. [ Links ]

Godinho P (2011) História de um testemunho, com Caixas em fundo. In Rodrigues A (2011) Gente Comum. Uma história na PIDE. 100LUZ, Loulé: 11-43. [ Links ]

Harrison P (2007) How shall I say it…?’’ Relating the nonrelational. Environment and Planning A, 39: 590-608. [ Links ]

Harvey D (1996) Justice, nature and the geography of difference. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. [ Links ]

Harvey S, Fieldhouse K (eds.) (2005) The cultured landscape. Designing the environment in the 21st Century. Routledge, Abingdon. [ Links ]

Hirsch E, O’Hanlon M (eds.) (1995) The anthropology of landscape. Perspectives on place and space. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [ Links ]

Hoelscher S (2009) Landscape iconography. In Kitchin R, Thrift N (eds.) International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. Elsevier, Amsterdam: 132-139. [ Links ]

Howells R (2003) Visual culture. Polity Press, Cambridge. [ Links ]

Isin E, Nielsen G (eds.) (2008) Acts of citizenship. Zed Books, London. [ Links ]

Jackson J B (1984) Discovering the vernacular landscape. Yale University Press, Yale. [ Links ]

Kienast F, Wildi O, Ghosh E (eds.) (2007) A changing world. Challenges for landscape research. Springer, Dordrecht. [ Links ]

Latham A (2003) Research, performance and doing human geography: Some reflections on the diary photograph, diary interview method. Environment and Planning A, 35: 1993-2017. [ Links ]

Leeuwen T (2001) Semiotics and iconography. In Leeuwen T, Jewitt C (eds.) Handbook of visual analysis. Sage Publications, London: 92-118. [ Links ]

Lorimer H (2008) Cultural geography: non-representational conditions and concerns. Progress in Human Geography, 32(4):551-559. [ Links ]

Lorimer H (2007) Cultural geography: worldly shapes, differently arranged. Progress in Human Geography, 31(1): 89-100. [ Links ]

Lorimer H (2005) Cultural geography: the busyness of being ‘more-than-representational. Progress in Human Geography, 29(1): 83-94. [ Links ]

Mailer P (1977) Portugal: the impossible revolution. Solidarity, London. [ Links ]

Martin R (2006) Artistic Citizenship: Introduction. In Campbell M, Martin R (eds.) Artistic citizenship: a public voice for the art. Routledge, New York: 1-22. [ Links ]

Martins J P, Loureiro R (1980) A extrema-esquerda em Portugal. História, 17: 8-23. [ Links ]

Matless D (2003) Introduction: the properties of landscape. In Anderson K, Domosh M, Pile S, Thrift N (eds.) Handbook of cultural geography. Sage, London: 227-232. [ Links ]

Mitchell D (2005) Landscape. In Sibley D, Jackson P, Atkinson D, Washbourne N (eds.) Cultural geography – a critical dictionary of key concepts. I.B. Tauris, London: 49-56. [ Links ]

Mitchell D (2003) California living, California dying: dead labour and the political economy of landscape. In Anderson K, Domosh M, Pile S, Thrift N (eds.) Handbook of cultural geography. Sage, London: 233-248. [ Links ]

Mitchell D (2002) Cultural landscapes: the dialectical landscape – recent landscape research in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 26(3): 381-389. [ Links ]

Mitchell D (1996) The lie of the land: migrant workers and the California Landscape. University of Minneapolis Press, Minneapolis. [ Links ]

Mitchell D (1994) Landscape and surplus value: the making of the ordinary in Brentwood, California. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 12: 7-30. [ Links ]

Mitchell W J T (1996) What do pictures “really” want? October, 77: 71-82. [ Links ]

Mitchell W J T (1994) Introduction. In Mitchell W J T (ed.) (2002) Landscape and power. 2nd Edition. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago: 1-4. [ Links ]

Mitchell W J T (1986) Iconology, image, text, ideology. Chicago University Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Nash C (2000) Performativity in practice: some recent work in cultural geography. Progress in Human Geography, 24(4): 653-664. [ Links ]

Olwig K (2005) Representation and alienation in the political land-scape. Cultural Geographies, 12: 19-40. [ Links ]

Olwig K (1996) Recovering the substantive nature of landscape. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 86(4): 630-653. [ Links ]

Panofsky E (1972 [1939]) Studies in iconology: humanistic themes in the art of the renaissance. Harper and Row, London. [ Links ]

Panofsky E (1970 [1955]) Meaning in the Visual Arts. Harmondsworth, Penguin. [ Links ]

Peet R (1996) Discursive idealism in the “Landscape-as-Text” School. Professional Geographer, 48(1):96-98. [ Links ]

Preziosi D (2009) Mechanisms of meaning. In Preziosi D (ed.) The art of art history: a critical anthology, 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 215-219. [ Links ]

Rolston B (2004) The war of the walls: political murals in Northern Ireland. Museum International, 56(3): 38-45. [ Links ]

Rose G (2007) Visual methodologies: an introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. 2nd Edition. Sage Publications, London. [ Links ]

Rose M, Wylie J (2006) Animating landscape. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 24: 475-479. [ Links ]

Salgueiro T B (2001) Paisagem e geografia. Finisterra – Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, XXXVI(72): 37-53. [ Links ]

Sluka J (1996) The writing’s on the wall. Peace process images, symbols and murals in Northern Ireland. Critique of Anthropology, 16(4): 381-387. [ Links ]

Smith R (2003) Baudrillard’s non representational theory: burn the signs and journey without maps. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21: 67-84. [ Links ]

Summers D (1995) Meaning in the visual arts as a humanistic discipline. In Lavin I (ed.) Meaning in the visual arts: views from the outside. Institute for Advanced Study, New Jersey: 9-24. [ Links ]

Swaffield S (2005) Landscape as a way of knowing the world. In Harvey S, Fieldhouse K (eds.) (2005) The cultured landscape. Designing the environment in the 21st Century. Routledge, Abingdon: 3-23. [ Links ]

Taylor J (1981 [1957]) Learning to look: a handbook for the visual arts. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. [ Links ]

Thrift N (2007) Non-representational theory: space, politics, affect. Sage, London. [ Links ]

Thrift N (1997) The still point: resistance, expressive embodiment and dance. In Pile S, Keith M (eds.) Geographies of resistance. Routledge, London: 124-151. [ Links ]

Thrift N (1996) Spatial formations. Sage, London. [ Links ]

Ventura A (1993) A oposição ao Estado Novo. In Medina J (ed.) História de Portugal: dos tempos pré-históricos aos nossos dias. Ediclube, Amadora: 149-205. [ Links ]

Wylie J (2007) Landscape. Routledge, Abingdon. [ Links ]

Recebido: Novembro 2009. Aceite: Agosto 2011.

NOTAS

2Portuguese Worker’s Communist Party/reorganizing Movement of the Proletariat Party. 3SEE http://www.fcsh.unl.pt/deps/antropologia/docentes/paula-godinho 4REORGANIZING Movement of the Proletariat Party, radical movement that later became the PCTP/MRPP . 5PCP: Portuguese Communist Party; CPSU: Communist Party of the SOVIET Union. 6A political struggle conducted within the MRPP concerning its strategy. Whereas ‘reds’ argued for a more radical approach, ‘blacks’ where in favor of a collaborative stance towards other organizations. 7INTERVIEW n7, male, 61. 8INTERVIEW n30, male, 63. 9INTERVIEW n10, male, 58. 10INTERVIEW n2, female, 53. 11INSTITUTO SUPERIOR TÉCNICO: technical University of Lisbon. 12People’s Democratic Union. RADICAL left party founded in 1974. 13INTERVIEW n24, female, 53.