Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

Share

Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia

Print version ISSN 0430-5027

Finisterra no.110 Lisboa Apr. 2019

https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis16035

ARTIGO ORIGINAL

"I have children and thus I drive": perceptions and motivations of modal choice among suburban commuting mothers

"Tenho filhos e por isso conduzo": percepções e motivações da opção modal de mães trabalhadoras residentes nos subúrbios

«J’ai des enfants c’est pourquoi je conduis»: perceptions et motivations des options modales des mères travailleuses résidentes dans la banlieue

"Tengo hijos y por eso conduzco”: percepciones y motivaciones de la elección modal de las madres con un desplazamiento suburbano al trabajo

Monika Maciejewska1; Carme Miralles-Guasch2

1 PhD candidate at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, España. E-mail: monika.maciejewska@uab.cat

2 Professor at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Campus de la UAB, Plaça Cívica, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, España. E-mail: carme.miralles@uab.cat

ABSTRACT

The mobility of mothers is often overloaded with a number of trips. The aim of this study is to understand the modal choice of mothers who commute to a suburban destination. The analysis takes into account trips related to all daily activities they are engaged in, and not just the commuting. However, the fact of having an intermunicipal trip to work is crucial since it conditions other travels. Using 15 in-depth interviews, we focus on feelings, perceptions and beliefs expressed by the respondents about their regular modal choice and the existing transportation alternatives. All participants commute to a suburban activity node in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region (Spain). Understanding the experience of this particular population segment may be useful to policymakers in creating effective programs and policies aimed at replacing car usage with more sustainable modes of transport.

Key words: Modal choice; women; determinants; mobility behaviour; qualitative; Barcelona Metropolitan Region.

RESUMO

A mobilidade das mães é muitas vezes sobrecarregada pelo número de viagens. O objetivo deste estudo é compreender a escolha modal das mães que viajam para um destino suburbano. A análise tem em considera ção as viagens relacionadas com todas as atividades diárias realizadas e não apenas as viagens casa-trabalho. No entanto, o facto de se realizar uma viagem intermunicipal para o trabalho é crucial, pois condiciona outras viagens. Realizadas e analisadas 15 entrevistas em profundidade, focamos os sentimentos, percepções e crenças expressas pelas entrevistadas sobre as suas escolhas modais habituais e alternativas de transporte existentes. Todas as pessoas entrevistadas viajam para um nó de atividade suburbana na Região Metropolitana de Barcelona (Espanha). Entender a experiência deste segmento populacional revela-se útil para os decisores políticos na criação de programas e políticas eficazes destinadas a substituir o uso do automóvel por modos de transporte mais sustentáveis.

Palavras-chave: Escolha modal; mulheres; determinantes; comportamento de mobilidade; qualitativo; Região Metropolitana de Barcelona.

RÉSUMÉ

La mobilité des mères est souvent surchargée par le nombre de voyages. L’objective de cette étude est de comprendre le choix modal des mères qui se déplacent vers un destin suburbain. L’analyse prend en compte les voyages liés à toutes les activités réalisées pendant la journée et non seulement ceux liés aux déplacements domicile-travail. Pourtant, le fait de se faire un déplacement inter-municipal vers le lieu de travail est crucial, une fois qu’il conditionne autres déplacements. Après réalisés et analysés 15 entretiens à fond, l’étude se concentre dans les sentiments, perceptions et croyances exprimés par les femmes interviewées sur les choix modaux usuels et les alternatifs de transport existants. Toutes les personnes interviewés voyagent vers un nœud d’activité suburbaine dans la Région Métropolitaine de Barcelone Espagne). Comprendre l’expérience de ce segment de la population est utile pour les décideurs politiques dans la création de programmes et politiques efficaces destinés à remplacer l’usage automobile par des moyens de transport plus durables.

Mots clés: Choix modal; femmes; déterminants; comportement de voyage; qualitatif; Région Métropolitaine de Barcelone.

RESUMEN

La movilidad de las madres a menudo está sobrecargada de número de desplazamientos. El objetivo de este estudio es comprender la elección modal de las madres que viajan por trabajo a un lugar suburbano. El análisis toma en cuenta los viajes relacionados con todas las actividades diarias que realizan y no solo los viajes al trabajo. Sin embargo, el hecho de tener un viaje intermunicipal al trabajo es crucial ya que condiciona otros viajes. Utilizando 15 entrevistas en profundidad, nos centramos en los sentimientos, percepciones y creencias expresados por los encuestados sobre su habitual elección modal y las alternativas de transporte existentes. Todos los participantes viajan a un nodo de actividad suburbano en la Región Metropolitana de Barcelona (España). Comprender la experiencia de este particular grupo de población puede ser útil para los políticos en la creación de programas y políticas efectivas orientadas a reemplazar el uso de automóviles con modos de transporte más sostenibles.

Palabras clave: Elección modal; mujeres; determinantes; comportamiento de viaje; cualitativo; Región Metropolitana de Barcelona.

I. INTRODUCTION

A review of the existent literature on mobility patterns from a gender perspective shows that women tend to use more often the modes of transport that are considered as more environmentally and socially sustainable. That is, they carry out a greater proportion of walking trips and use public transport more often, while men tend to rely more on private modes of transport (Polk, 2003; Levy, 2013; Scheiner, 2014; BasariÄ VujiÄiÄ, SimiÄ, BogdanoviÄ, SauliÄ, 2016; Mahadevia & Advani, 2016). Women, however, are not a homogenous group and depending on their life situation and territorial context, their mobility habits may differ (Goddard, Handy, Cao, & Mokhtarian, 2006). Middle-aged women, in particular, are in a life stage which usually corresponds to being active in both professional and domestic areas, and have been found to have mobility habits that are closer to the traditionally male, car-oriented model (Miralles-Guasch, Melo, & Marquet, 2015). Among them, middle-aged women with young children to take care of, tend to be even more car-dependent in order to accommodate home, work and childcare obligations (Vance & Iovanna, 2013). Female modal choice is also strongly determined by built environment attributes. Suburbs, characterized by low density and poor diversity, generally do not have enough public transport supply to meet the needs of individuals who may depend on it. These circumstances, along with street design, induce reliance on a private vehicle. In consequence, women who either live in a suburban, low-density area or who have to move within these areas are more likely to move by car, which provides them with more flexibility to accomplish their every day trip-chains (Dowling, 2000).

In addition to individual variables (such as gender, age) and environmental variables (infrastructure, facilities), there are also subjective factors that play an important role in choosing the mode of transport. A better understanding of the motivation that leads women with a specific profile to certain mobility behaviours – such as choice of a mode of transport – is necessary to design effective public policies aimed at reducing car use. This paper provides information about the reasoning suburban-commuting mothers are guided by, in their daily modal choice. This new understanding should lead to strategies to encourage women to replace the car with an alternative. In consequence, besides redirection of the current use of transport to more sustainable modes, as simultaneous effect, children raised in a non-car-dependent model might naturally adopt it as their own and follow it in the future (Pérez & Capron, 2018). Switching the model sometimes can take a generation, so the current mission is to start educating children according to the new principles (Sattlegger & Rau, 2016).

The present study used a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods. Using a representative survey as background data and carrying out face to face interviews for the in-depth analysis. The following section starts with an overview of the existing research on determinants of Modal Choice, focusing on the special case of mothers with suburban commuting. Next, section III introduces the spatial context, as well as explaining the study design. Results are organized in two sections: the quantitative context data are presented in section IV, followed by the qualitative analysis of interviews in chapter V. Finally, the article concludes pointing out the most important findings and highlighting the contributions of the paper in section VI.

II. BACKGROUND

1. Suburban commuting and car dependence

Commuting, generally understood as a regular trip to work, is an integral part of everyday mobility (Sandow, 2008). The main characteristic of this particular trip is the fixation in time and space. This fact is related to both rigidity schedule on workdays, and lower flexibility to choose a job than to decide where to go shopping or which activities to engage in (McGuckin & Srinivasan, 2005). When the workplace is located in peripheral areas, sprawl or suburbs, travel to these destinations is characterized by long distance and long travel time. To describe its extended duration, literature has developed the concept of intensive commuting (Ravalet, Vincent-Geslin, & Dubois, 2016), however, its temporal definition varies significantly between places. In the context of European metropolitan areas such as Paris, London (Jones, Massot, & Orfeuil, 2008) or Barcelona (Delclòs-Alió & Miralles-Guasch, 2017), it has been set from 60 minutes for a round trip onwards. In terms of distance, it greatly exceeds the range of active travel and thus forces employees to rely on motorized modes of transport.

Within the constrained modal choice of motorized transport, the choice between private vehicle and public transport is influenced by a combination of location, density and morphology (García-Palomares, 2010; Delbosc & Currie, 2011) of the environment around both the residence and the workplace, as well as on the infrastructure and services available. Over the last decades, many studies have argued that in out-of-city work-related trips, the use of car tends to prevail. The switch from public transport to car was observed in the late 1980s caused by the relocation of jobs from the downtown to the suburbs of San Francisco (Cervero & Landis, 1992). Aguilera and Mignot (2002) studied car reliance in France, and found that the car was needed in nine out of ten intermunicipal work trips. According to Limtanakool, Dijst, and Schwanen’s (2006) findings from Netherlands, 85% of commuting trips with a suburban destination are undertaken by automobile. In a case study from Lisbon, commuters were found to increase car travel after their workplace had been relocated to a suburban area (Vale, 2013). This general car-reliance phenomenon can be explained with different arguments. First, in large part it can be attributed to the prioritization of road infrastructure in the current shape of the metropolitan areas and to the fact that suburbs are generally supplied by public transport in much lower extents than the city (Rodríguez Moya & García-Palomares, 2012). Second, the use of a car is also conditioned by social and economic factors. During the now decade long world economic recession, Spain and France -two countries where car ownership among intensively mobile people is over 90%- experienced a growing willingness to accept long-distance commuting in order to get a job (Schleith & Horner, 2014; Ravalet et al., 2016). In other studies, the willingness to engage in private car suburban commuting has been associated with optimization of time (Vega & Reynolds-Feighan, 2009). Since private car is expected to be the fastest way of travel, people generally choose this mode in order to shorten time invested in traveling (Mackett, 2014). This need arises especially for those who have an intensive commuting because it affects other trips of the day.

2. Beyond commuting. Beyond built environment determinants

Besides the conditions imposed by the built environment, mobility patterns depend heavily also on individual attributes, and because of that, they vary between different social groups, as a result of people’s particular needs and resources (Oakil, Nijland, & Dijst, 2016). Gender and age are among the personal characteristics most often examined. Scholars have found that travel behaviour differs between age groups and is deeply gendered (Queirós & Marques de Costa, 2012; Peters, 2013), as it reflects power relation dynamics existing in society. Gender asymmetries are evident in both the frequency of trips made for different purposes and in the use of transport modes. Women’s personal mobility tends to be more complex than men’s, due to the abundance of obligations which generate many maintenance and care-related trips (Roberts, Hodgson, & Dolan, 2011). The combination of intensive commuting determining the characteristics of trips made throughout the day, and the fact that women tend to engage in more trips per day, makes the outcomes of intensive commuting to be deeply gendered. Regarding transport modes, women, in contrast to men, are more likely to use public transport and walking, at the same time that they rely less on private vehicles (Miralles-Guasch et al., 2015). This can be the result of both, limited access to a private automobile, as traditionally the man has priority in using it (Boarnet & Hsu, 2015; Solá, 2016), or female preferences towards the alternative modes (Scheiner & Holz-Rau, 2012; Vance & Peistrup, 2012).

However, women are not a homogenous group. Their mobility patterns evolve throughout the life, adapting to the needs of subsequent life-stages (Goddard et al., 2006). Middle-aged women are characterized by particular practices that often are a result of their mobility behaviour being dependent to a greater extent than that of others. They usually have to combine the role of employee with that of caregiver of children (and often also of senior parents), and they have been identified by some authors as the generation of support (Camarero & Oliva, 2008; Camarero, Cruz, & Oliva, 2016). Despite the current trend of convergence in the distribution of family care, women are still charged with a disproportionate responsibility for children care (Hanson & Pratt, 1995; Best & Lanzendorf, 2005). Therefore, in addition to the everyday commute to work, mothers are also usually responsible of a wide range of mobility for care reasons such as household-related trips, escorting dependents, grocery shopping etc. (Sánchez de Madariaga, 2013). As proved by Motte-Baumvol, Bonin, and Belton-Chevallier (2017) two thirds of the shuttling travels fall to mothers. Due to this chauffeuring mobility, middle-aged women tend to increase their car-use and car-dependence (Cresswell & Uteng, 2008), especially while children in their charge are below 10 years old (Scheiner, 2014).

In addition to personal attributes and features of the built environment, subjective motivations, perceptions and beliefs may also play a decisive role in modal choice (Garcia-Sierra, van den Bergh, & Miralles-Guasch, 2015). Schneider (2013) proposes a Theory of Routine Mode Choice Decision which takes into account those determinants. The model describes a decision-making process consisting of the following elements: 1) availability of options; 2) perception of security; 3) beliefs about convenience; 4) enjoyment (such as comfort perception) and 5) habit. Each of these steps, strongly depends on individual attributes such as gender, especially those related to individual perceptions given how gender sensitive these are. Overall, however, more research is needed to understand the factors behind employed mother’s car dependency. Literature has not yet provided evidence on the gendered relationship between motherhood, specific life-stage and travel behaviour, especially in the constrained context of a suburban commute.

Aiming at this gap, the present study attempts to provide a deeper understanding of subjective motivations that may be influencing the modal choice of employed mothers who commute to a suburban workplace. In the following section, the methodology of the study is explained. Afterwards, the results section is structured through 1) a brief quantitative introduction and some background data – in order to present the modal split of the female Autonomous University of Barcelona employees while commuting – and, 2) findings from fifteen face-to-face interviews aimed at exploring the issue of their relations with modes of transport. Lastly, the paper ends with a conclusion.

III. METHODOLOGY

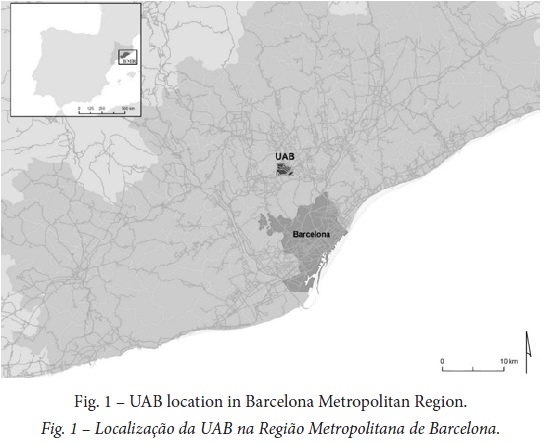

1. Location context and UAB community

The study focuses on the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and its employees. The campus is an example of a suburban activity node, which generates a large number of round trips. It is located in the border between the first and second metropolitan ring of the Barcelona Metropolitan Region (BMR), 23km from the capital city (fig. 1). The polygon is located in an intersection between two major motorways and has a wide range of public transportation connecting other localities in the area: there are three railway stations and several interurban bus lines (Miralles-Guasch, Avellaneda, & Cebollada i Frontera, 2001). The UAB’s population is approximately 40 000 individuals, of which 16,5% corresponds to faculty and administrative staff. Living in different, near or distant, municipalities makes their commuting consist of an inter-municipal trip. Among this group high car ownership that exceeds 75% of members has been detected. Most of them are car commuters and many have an intensive commute (GEMOTT, 2017).

2. Study design: survey and interviews

The aim of this study is to understand how certain profiles of women explain their relations with the modes of transport they use. The subjective factors that condition modal choice were identified among intensive commuter working mothers, selected as a specified-profile homogeneous group with similar needs (Wedel & Kamakura, 1998). Quantitative background data allows the detection of patterns of a social group, but it is not enough to deepen understanding of the issue. For an open research process giving the participants the opportunity to express their opinion, perceptions and explanatory reasons for their behaviour and choices, the use of qualitative methods was needed. Once the specific group was identified and its behaviour was measured quantitatively, individual interviews provided information about their decision-making process of modal choice.

The quantitative data comes from the 9th edition of the University Community Mobility Habits Survey (hereinafter UCMHS) from UAB held among the university community in spring 2017 (previous editions used by (Miralles-Guasch & Domene, 2010; Miralles-Guasch, Martinez-Melo, & Marquet, 2014; Delclòs-Alió & Miralles-Guasch, 2017). It was designed in order to understand community members’ commuting travel patterns. A total of 3 554 questionnaires were selected through stratified group sampling. The confidence level was set at 95.5% with a relative error of ±1.57%. The present study focuses on female staff respondents, so the final sample comprises 694 participants. The analysis of descriptive statistics was performed in IBM SPSS version 19.

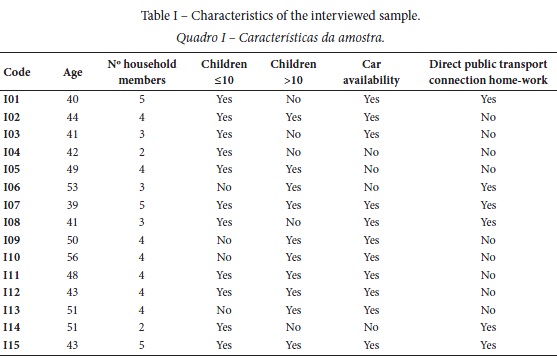

Next, in order to achieve depth of analysis, a total of 15 interviews were carried out with women employed at the UAB Campus in spring 2017. Regarding the sociodemographic and cultural profile, it is a fairly homogeneous group. They are middle-aged, with a double role as mothers and workers. In addition, they share commuting trip characteristics: the same purpose, the same suburban destination and the need to use motorized transport. On the other hand, to avoid the location bias, the sample is composed of staff from different areas of the campus, living in different municipalities and having different access characteristics (table I). Most of them are married or in stable relationships; two are single mothers. Eleven of have children who are ten years old or younger, considered as dependent who need care in all their trips. Except for the two women from lone parent households, all participants declared car availability. However, during the conversation it turned out that two shared the car with their partner since they travel to the same workplace and two did not usually use the car because it was mostly used by their partners. To ensure confidentiality, each person was given a number to encode their personal data. In order to be able to compare the answers, the conversations were based on a semi-structured discussion guide with key open-ended questions (as in Noack, 2011) regarding mobility patterns and took 30 minutes on average. With the permission of the participants, the conversations were audio recorded. The collected material has been transcribed verbatim, coded according to the emerging concepts, and analysed. The qualitative research software MAXQDA© Plus v10.9.8.1 was used to facilitate coding and data analysis. The analysis is based on the constant comparative grounded theory technique (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The number of interviews was based on two criteria: 1) the saturation concept (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006) and 2) the minimum number of interviews in other studies (Guggenheim & Taubman - Ben-Ari, 2013; Mitra, Siva, & Kehler, 2015; Sattlegger & Rau, 2016).

IV. BACKGROUND DATA

An average woman from BMR invests 46 minutes per day in commuting (EMEF2015), while one who works at UAB spends 78 minutes (2.6 times more). This longer work-related travel along with a highly demanding mobility of care -especially common among mothers- affect their daily time budget and can be the source of a constant hurry. Therefore, the time pressure can be reflected in the mobility strategies and the choice of mode of transport. Indeed, a 62% majority of the UAB women workers reaches the campus in a private vehicle, while 35% declare to get there on public transport (GEMOTT, 2017). This high car reliance brings women closer to the traditional male trend. However, even when women rely more often on the car, they use it differently than men. As women are more likely to combine commuting with escorting or other household-related trips, their travel to work is more complex, and therefore more time consuming, than males (Dobbs, 2005). Given this use of modes of transport among targeted women, it was considered appropriate to deepen our understanding of how they make their modal choice.

V. QUALITATIVE FINDINGS

Due to the space-time dispersion of activities of women under study, a great part of their daily mobility is characterized by the use of motorized transport, public or private. The mode of transport they mainly use conditions their perception on both this mode and other existent options. Habitual car drivers and regular public transport users express different argumentation about the mode they use and show a different attitude towards the alternative, hence their experience is presented separately in the following 1 and 2 sections.

1. Car users

First of all, a noteworthy fact is that all the interviewed women who have access to the car for their own use, declare to use it regularly. They do not consider travelling by transit as feasible. It seems that car availability makes women blind to public transport as an option. Whereas it had been found so far in rural areas, for example in Scotland by Noack (2011), it seems that the same happens in metropolitan areas, even with a dense public transport network. However, during the conversation about their usual modal choice, a sense of guilt appears. As these women rely on a private vehicle despite being aware of harmful consequences of this mode for the environment, it seems that admitting to car use evokes embarrassment, remorse and the need to justify that behaviour.

In consequence, the interviewees indicate the causes of this car-dependent state of affairs. The main condition to which they attribute the blame for it is the presence of children in the household. It contributes to the claim that mobility does not depend only on oneself but also on other members of the household (Plaut, 2006). Moreover, identifying children as a direct determinant of adults’ modal choice is in line with findings of Rau and Manton (2016). Apparently, "when you're a mother, your habits change a lot. So now we use the car much more" (I08). As described in the following paragraphs, not all but many arguments in favour of car use are related to children. What is more, driving mothers are convinced that currently they cannot change their habits, but they mention hypothetical scenarios of change in the future: "Now we use the car much more than I would really like according to my way of understanding of life (I08) I hope we can change when the children grow up" (I01). The following paragraphs show the four main arguments used by the interviewed mothers, which induce them to use the car: time, comfort, habit and economic issues.

1.1. A matter of time consumption

"When I did not have children, I always came [to work] by train, because I was not in a hurry" (I13). This statement suggests that, in fact, relating driving with children is due to time pressure, caused by many obligations related to coordination of dual roles as mother and earner (Best & Lanzendorf, 2005; Wheatley, 2014). Time perception has appeared to be the most-mentioned explanatory factor of modal choice and is related to many different issues. The link between time and children is frequent in the context of the justification for the use of a car, mainly in context of multi-person and multi-destination trips, commented below.

Accompanying the children to the nursery or school during the travel to work makes it became a trip chain (Rosenbloom, 1989; Greed, 2005; Pitombo, Kawamoto, & Sousa, 2011). Many mothers stress that they need a car due to the complexity of the trip chains (Dobbs, 2005). As they articulate, the afternoon route is often even more complex than the morning one. It consists of picking up children, taking them where appropriate, to their extracurricular activities, which are located in different places and have an established schedule. "There are quite a few trips. I do not chauffeur the two kids to the music class and I pick them both up. No, I escort one of them, after an hour I drop off the other picking up the first one, and then I back to pick him up too" (I15). Making the trip chain even more complex, mothers usually take advantage of the time that the after-school class lasts for shopping or other errands. If they go to the supermarket they appreciate the role of the car so as not to have to carry weight.

The reliance on the car is thus due to the multitude of trips women execute during the day and due to the stress of having to arrive on time. The following is a typical statement highlighting the essentiality of the car, otherwise it would be not feasible to get anywhere: "Our children depend on us, depend on we can get there. (I02) You drive, or you do not arrive on time" (I01).

Women explain that they are less willing to use public transport while traveling with children because this way the ride is not door to door and it is necessary to walk to and from the station. Walking with small children "is slow, it lasts as long as they need" (I01), so in order to save time, they often decide to make these family trips by car. In many cases, the parent who takes the children, carries the car. "The car belongs to kids (I15). If I go alone, I go fast by train" (I01). However, in fact, not always more than one seat in the car is occupied. That is justified with an argument opposed to what has been said above. Some mothers, reminisce than when their children were babies, they also used the car when travelling alone. They justify this behaviour with the quickness of the round trip and then having more time for the little ones.

As many mothers feel under pressure to comply with all activities, they seek to optimize time wherever is possible. Car users seem to be convinced that, in terms of time, they cannot afford to move on public transport. They express opinions such as "In weekdays, we go with a timer – as I often say - so we drive (I01). It's faster by car" (I07). “If I had time, for me going by public transport would be a luxury because you are sitting without having to worry about traffic lights, parking… But I can’t!" (I12). Actually, some car users, who recognize the advantages of going on public transport but do not use it, need to justify their actions and try to find advantages to what they do: "On the train you have time to read a lot, and in the car, you can’t do it. But hey, I've gotten used to the radio, I catch up with the news. You are finding advantages, as you have no choice…" (I09). It is surprising that precisely car drivers talk about having no choice, when they are the ones who can really choose from the existing alternatives.

Another time-related determinant of car use is the lack of direct public transport connection with destination. Several women mention it as a barrier. They perceive that travel time is extended even if the transfer is short. Moreover, it seems that they do not want to do it, more as a precaution, as travel time could be potentially extended in case of desynchronization, than by the real inconvenience that it entails. "The transfer is not bad, it is short. You have to wait a bit. But if something happens…" (I09). It is striking that they do not mention the possibility of travel time extension due to a traffic jam or accident, when driving. In fact, there are suspicions that the transfer-related extension in time may be just a perception issue. "I don't know if it's a real or mental thing. It provokes us a kind of distortion (...). We feel much calmer and free having the car parked right here" (I10).

1.2. As comfortable as possible

Having said so, it seems evident that beyond time, there is a kind of comfort perception in question. "There are 15 minutes of difference. But take the three children to the station then climb the hill to school… I think it's that, both, but rather comfort than time" (I15). Women often rely on car because they consider going by public transport as tiring. The concept of comfort is connected to a subjective perception of convenience. The interviewees reveal that the car provides the comfort of not having to pay attention to connection combinations and to check schedules. Moreover, as several mothers state, the car is more convenient especially when traveling with babies in a stroller or when toddlers get tired and "if they fell asleep in the car, no worries" (I02) while if it happens in public means women see it as "very complicated (I08). Moving kids by metro was a show" (I10). This explanation contributes to the findings about convenience pointed out as the main argument in favor of the car among UAB staff in (Miralles-Guasch et al., 2014).

1.3. Habit as difficulty to change repeated actions

Attributing the cause of the use of the car to the fact that the children are very small and traveling with them in alternative modes is difficult, suggests anticipation of change once these circumstances pass away. As aforementioned, some mothers of small children explicitly express desire to resign from the car in the future. Nonetheless, the interviewees with older children indicate the habit as key factor in their modal choice. "I've already gotten used to driving. And now it would cost me a lot [of effort] to get back to the train" (I09). As a result, that attachment to the car tends to grow instead of decreasing as beliefs and habits intensify over time (Scheiner, 2014). It seems that drivers regular practice becomes such a deep-rooted habit that even when children are not small any longer, they still try to blame them: "when you have teenage children, time is also very important for them. If I were alone with my partner, maybe we would go by train" (I10). As shown, they keep making excuses, but always leaving room for potential change if the circumstances are different. The explanation of these circumstances partly responds to the need of deep exploration of the formation of driving habits suggested by Garcia-Sierra, Miralles-Guasch, Martínez-Melo, and Marquet (2018).

1.4. Economic issue – what is the real price?

Another type of determinant in the decision-making process of using one mode or another is the economic issue. Car users often underestimate the real cost of their use, especially in relation to the price of public transport (Garcia-Sierra et al., 2015). That happens because this kind of argument often appears linked to the price comparison of a singular trip, without taking into account maintenance, insurance, car revision and repairs. The interviewees have relied on this reasoning referring to multi-person trips. It has been possible to hear comments like the following: "The ticket is very expensive. You calculate and paying the parking is almost more economic" (I02).

When it comes to travelling alone, for example to work, many women do take into account other factors beyond the cost of petrol. They are aware of investing more money in total, but they immediately contrast it with the information about benefits provided by the car. "By car, I spend more. Ok, because you have gas and everything that happens in the car, it breaks down or something comes up. The train, well... it's economic and not economic... [I spend] More money but I save time" (I03). This reasoning is in line with the trend of putting time value over economic cost mentioned by Carmo, Santos and Ferreira (2017).

As the literature states, once reached the resources to afford the purchase of the car, it is difficult to resign from using it (Dargay, 2001), even though the interviewed users feel obligated to justify their behaviour. This reliance could be related to the factors mentioned beforehand as habit, comfort and deep conviction of saving time. Car users tend to overuse this mode, relying on it not only as a substitute for public transport, but even for short, walking distances (Loukopoulos & Gärling, 2005).

2. Public transport users

Everyday passengers of public transport show a different attitude than drivers talking about their patterns. They do not feel obliged to justify themselves, rather they talk about their experience.

An outstanding distinguishing point is, that these women do not mention children as an obstacle that hinders the use of public transportation. They have traveled with children in different means of public transport and they express satisfaction with this practice: "Even with small children it's more convenient. Driving is a stress and then, parking..." (I06).

The interviewees who usually go on public transport do not seem to have similar feelings to drivers about the indispensability of the private vehicle. An exception is the vision of an emergency situation: "If they call from the school saying that my child has been sick, in that moment, I wish I had a car." (I05).

Women accustomed to being passengers of public transport are aware of some weak points of this mode, but do not consider their own experience as negative. They do not complain about not having a private vehicle available for themselves. Also, contrary to the findings from the UK, reported by Wheatley (2014), about lower job satisfaction by public transport users compared to drivers, no similar phenomenon was noted in the present study.

Nevertheless, besides some contrasts there are also some similarities. It is noteworthy that this group uses the same categories of arguments – economy, comfort/convenience, habit and time – in favour of their mode choice, but from a different, sometimes opposed perspective.

In their case, the lack of car has different causes. One of them is the economic factor - they cannot afford to run it or they think it is an unnecessary expense. As they claim: "Having children at charge, the salary does not allow me to have a car on my own" (I05) and "Day-to-day I don’t need it and just for some weekends it is better renting it. And there is no parking. Oh no, it is an expense, in my case, quite senseless" (I14). Other reason is just not like driving, so the car does not look like a comfortable option: "I have a driver's license, but I do not use it, because I find it less convenient. Parking in the city centre is complicated" (I06). Another reason for not wanting nor missing the car is the simple fact of not being used to that alternative and not having created a dependency: "I've never had a car" (I04).

Not being contaminated by the tendency to idealize the car, and especially by knowing public transport firsthand, its users value this mode positively: "The public transport is fast, there are usually no problems" (I06). Public transport travellers do not consider their trip as a waste of time at all, but take advantage to carry out productive or enjoyable activities (Sattlegger & Rau, 2016) such as reading, writing emails, using social networks, making plans or sleeping: "On the train I do many things. I read a lot, people usually cannot do that. I sleep (I05). I use the time to read or answer emails" (I04). The last is in line with Gripsrud and Hjorthol's (2012) findings about the positive effect of the use of information and communication technology, while travelling by train, on the perception of travel as a useful time.

It is noticeable that this group mentions disadvantages of driving, while the regular drivers do not reveal a similar perception: "The car provides you more freedom (…), but you can get stuck in a traffic jam on the motorway (I06). I would take more by car than by public transport. I would have to leave at 6.30 in the morning or at 7 to avoid traffic jams (I14)".

VI. CONCLUSIONS

A 62% majority of the UAB female workers reaches their place of work in a private vehicle. In order to understand that behaviour we asked mothers with suburban commuting about their modal choice and found that it depends on different kinds of factors. The accessibility to different transport modes -car availability and public transport supply- is undeniably the primary condition to be able to use them. Besides, the modal choice is conditioned by individual perceptions and habits. It has been found that most of perception-based explanations for car use have to do with time and comfort. Routines, which become habits, have also been found to be an important determinant. It especially works for drivers, as -according to them- once one gets used to a car it is hard to change the pattern. Security issues do not appear as an argument in favour of this mode, positioning the car above the alternative. This silence means that public transportation in BMR is perceived as safe – an issue which might have come to light negatively in many other contexts (Delbosc & Currie, 2012; Rozas Balbontín & Salazar Arredondo, 2015).

A similarity detected among both interviewed groups is that the users of a given mode of transport refer to the disadvantages of the other mode, not mentioned by their own users. Namely, drivers remark on possible delays of transit due to breakdowns or uncoordinated transfers, while public transport passengers indicate the traffic jams and the need to implement strategies such as leaving home very early to avoid them.

The analysis also revealed how the point of view differs between those two groups. First, it turns out that car users are more likely than public transport passenger to miss the mode they do not use. They show it expressing their concern about the environment -a common female concern (Matthies, Kuhn, & Klockner, 2002)-, as well as the desire of taking advantage of the time of the journey instead of having to pay attention to the road. However, they are convinced they cannot switch. Secondly, the interviewees who choose the car emphasize and prioritize the quickness of travel by this mode, although -as they recognize- travelling by bus or train they could do something in the meantime. Transit passengers, instead, focus on advantages of the mode they use valuating their experience as more convenient and less stressful than driving. Moreover, while the latter don’t mention children as a factor which hinder trips in this mode, car enthusiasts tend to state that public transport trips with kids becomes slow, tiring and annoying.

It seems like having children is a perfect excuse for using the car. Sometimes, even if the mothers drive alone, they still say it is due to the children, for saving time and spending it with them. Anti- public transportation arguments related to the children are evolving depending on the age of the children: from the fatigue of the stroller, little ability of pre-schoolers to walk quickly, the need to make multiple escort trips and arrive on time -of those who are not yet independent-, to the reluctance towards public transport of teenagers.

There have appeared voices that the cars are for children and it does not matter which of the parents drive them. But, as mothers usually make more escorting trips (Motte-Baumvol et al., 2017), children strongly condition female mobility behaviour. From the argumentation of interviewed drivers, it turns out that they, as working mothers, are overwhelmed by responsibilities and pressed for time (Rosenbloom & Burns, 1994). It reflects the still present gender differences in the division of reproductive labour, which results in women having a second, unpaid, shift at home (Hochschild, 1989). Although the dynamics of division of domestic work has a convergent tendency among genders (Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, 2006), the traditional model continues to have negative repercussions for women (Sayer, 2010).

At this point, it is worthy to pay attention to the two participants characterized by the intersectional element of being single mothers. Their situation assumes shouldering alone the full burden of domestic and professional work, which strongly stresses their time and economic resources, at the same time that they deal with the additional burden of daily travel (Lee, Vojnovic, & Grady, 2018). In line with the idea that time pressure forces women to use the car, it would be the single mothers the ones who would travel in this mode more often. In this case, however, it is exactly the opposite, which in part may result from not having a car available, likely to happen in one-earner household. However, the interviewed single mothers do not appear to miss driving, but rather consider public transport as an efficient mode for them.

Without denying the fact that mothers juggle a lot of parenting tasks (even if shared), it is important to notice that part of the problem may rise from the choice of activities of their children and assumption that having a car will grant them quick access everywhere. From this point of view, it is understandable why they consider having no alternative to using the car. However, they could have structured the everyday activities (theirs and those of their children) considering accessibility based on public transport, just like other mothers, who do not have a car. While the house and the workplace are "fixed" destinations, all the rest are destinations that they or their families have in part chosen. Thinking that they have no other option than using the car is self-serving bias. However, another possibility is that in some cases more convenient -in terms of access- alternatives were not available, so they could only access those activities thanks to the car.

The study contributes to the growing academic literature based on qualitative approaches. Through interviews, it has been possible to explore in depth specific profiles and women's motivation for their choices. The findings corroborate working mothers' time constraints due to their engagement in double shifts, which brings many of them to use a car as a tool which enables managing all activities throughout the day (Dowling, 2000). Moreover, it has been shown that regardless of the mode of transport people use, they are convinced of the convenience of their choice. Gaining knowledge on this subject can be useful to the policymakers in creating effective programs and policies aimed at replacing the car with more sustainable alternatives. These interventions are expected to have double-dimensional outcomes. On the one hand, they would redirect working mothers’ patterns and would make them take advantage of the benefits of using public transport. On the other hand, as long-term effects, children raised in a non-car-dependent model might naturally adopt the more sustainable transport options as their own patterns and follow them in the future (Mackett, 2002).

Given that the outcomes of intensive commuting are deeply gendered due to imbalanced share of household-related duties, there is also no doubt that political agendas should address family-work issues (Stanfors, 2015) in order to provide equal opportunities to both men and women. However, additionally there is a need for gender equality social campaigns to normalize the adaption of a gender-equal household model. As an example, in Spain, despite of the existence of the right to reconciling work and family life, only a marginal percentage of fathers use it -less than 8% of all cases in 2017 (IMIO, 2018)- because this practice is currently not sufficiently socially embedded. As a result, mothers are often those who have to combine work with daily family care, including mobility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the pre-doctoral contract FPU 2016 awarded by The Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain. The research has been also possible thanks to financial support received from the Project CSO2016-74904-R.

REFERENCES

Aguilera, A., & Mignot, D. (2002). Structure des localisations intra-urbaines et mobilité domicile-travail. Recherche Transport Sécurité, 77, 311–325.

BasariÄ, V., VujiÄiÄ, A., SimiÄ, J. M., BogdanoviÄ, V., & SauliÄ, N. (2016). Gender and Age Differences in the Travel Behavior - A Novi Sad Case Study. Transportation Research Procedia, 14, 4324–4333. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.354

Best, H., & Lanzendorf, M. (2005a). Division of labour and gender differences in metropolitan car use. An empirical study in Cologne, Germany. Journal of Transport Geography, 13(2), 109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2004.04.007

Best, H., & Lanzendorf, M. (2005b). Division of labour and gender differences in metropolitan car use. An empirical study in Cologne, Germany. Journal of Transport Geography, 13, 109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2004.04.007

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage. [ Links ]

Boarnet, M. G., & Hsu, H. P. (2015). The gender gap in non-work travel: The relative roles of income earning potential and land use. Journal of Urban Economics, 86, 111–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2015.01.005

Camarero, L. A., & Oliva, J. (2008). Exploring the social face of urban mobility: Daily mobility as part of the social structure in Spain. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32(2), 344–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00778.x

Camarero, L., Cruz, F., & Oliva, J. (2016). Rural sustainability, intergenerational support and mobility. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), 734–749. doi: 10.1177/0969776414539338

Cervero, R., & Landis, J. (1992). Suburbanization of jobs and the journey to work: A submarket analysis of commuting in the San Francisco bay area. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 26(3), 275–297. doi: 10.1002/atr.5670260305

Cresswell, T., & Uteng, T. P. (2008). Gendered Mobilities: Towards an Holistic Understanding. In T. P. Uteng and T. Cresswell (Eds), Gendered Mobilities (pp. 1-12). Farnham: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Dargay, J. M. (2001). The effect of income on car ownership: evidence of asymmetry. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 35(9), 807–821. doi: 10.1016/S0965-8564(00)00018-5

Delbosc, A., & Currie, G. (2011). The spatial context of transport disadvantage, social exclusion and well-being. Journal of Transport Geography, 19, 1130–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2011.04.005

Delbosc, A., & Currie, G. (2012). Modelling the causes and impacts of personal safety perceptions on public transport ridership. Transport Policy, 24, 302–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.09.009

Delclòs-Alió, X., & Miralles-Guasch, C. (2017). Suburban travelers pressed for time: Exploring the temporal implications of metropolitan commuting in Barcelona. Journal of Transport Geography, 65, 165-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.10.016 [ Links ]

Carmo, R. M., Santos, S., & Ferreira, D. (2017). “Unequal mobilities” in the Lisbon metropolitan area: Daily travel choices and private car use. Finisterra - Revista Portuguesa de Geografia, LII(106), 29–48. doi: 10.18055/Finis10102

Dobbs, L. (2005). Wedded to the car: Women, employment and the importance of private transport. Transport Policy, 12(3), 266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2005.02.004

Dowling, R. (2000). Cultures of mothering and car use in suburban Sydney: a preliminary investigation. Geoforum, 31, 345–353.

García-Palomares, J. C. (2010). Urban sprawl and travel to work: the case of the metropolitan area of Madrid. Journal of Transport Geography, 18(2), 197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2009.05.012

Garcia-Sierra, M., Miralles-Guasch, C., Martínez-Melo, M., & Marquet, O. (2018). Empirical analysis of travellers’ routine choice of means of transport in Barcelona, Spain. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour , 55, 365–379. doi: 10.1016/J.TRF.2018.02.018

Garcia-Sierra, M., van den Bergh, J. C. J. M., & Miralles-Guasch, C. (2015). Behavioural economics, travel behaviour and environmental-transport policy. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 41, 288–305. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2015.09.023

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). Discovery of Grounded Theory (Aldine). Chicago: Aldine Transaction. Retrieved from http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf

Goddard, T., Handy, S., Cao, X., & Mokhtarian, P. (2006). Voyage of the SS Minivanâ¯: Women’s Travel Behavior in Traditional and Suburban Neighborhoods. Transportation Research Record, 1956(1), 141–148. doi: 10.3141/1956-18

Greed, C. (2005). Overcoming the Factors Inhibiting the Mainstreaming of Gender into Spatial Planning Policy in the United Kingdom. Urban Studies, 42(4), 719–749. doi: 10.1080=00420980500060269

Gripsrud, M., & Hjorthol, R. (2012). Working on the train: from ‘dead time’ to productive and vital time. Transportation, 39(5), 941–956. doi: 10.1007/s11116-012-9396-7

Grup d’Estudis en Mobilitat Transport i Territori. (GEMOTT). (2017). Enquesta d’Hàbits de Mobilitat de la comunitat universitària de la UAB 2017 [Mobility Habits Survey of the UAB university community 2017]. Retrieved from http://www.uab.cat/doc/resum_executiu_EHMUAB2017

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability and a good number of journals in the. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–882. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Guggenheim, N., & Taubman-Ben-Ari, O. (2013). Women who DARE: driving attitudes and road experiences among ultraorthodox women in Israel. Gender, Place & Culture, 21(5), 533–549. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2013.802670

Hanson, S., & Pratt, G. (1995). Gender, work and space. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hochschild, A. R. (1989). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking Penguin. [ Links ]

Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. (IMIO). Mujeres en Cifras - Conciliación - Excedencias, permisos y reducciones de jornadas: Excedencia por cuidado de hijas/os. http://www.inmujer.es/estadisticasweb/6_Conciliacion/6_2_ExcedenciasPermisosyReduccionesdeJornada/w121.xls Accessed February 18th 2019

Jones, M.-H., Massot, J.-P., & Orfeuil, L. P. (2008). Links between Daily Travel Times and Lifestyles of Families. Paris and London, Rapport Final de Contrat Pour La Fédération Internationale Automobile (FIA Foundation), fé vrier (2008). [ Links ]

Lee, J., Vojnovic, I., & Grady, S. C. (2018). The “transportation disadvantaged”: Urban form, gender and automobile versus non-automobile travel in the Detroit region. Urban Studies Journal Limited, 55(11), 2470–2498. doi: 10.1177/0042098017730521

Levy, C. (2013). Travel choice reframed: “deep distribution” and gender in urban transport. Environment and Urbanization, 25(1), 47–63. doi: 10.1177/0956247813477810

Limtanakool, N., Dijst, M., & Schwanen, T. (2006). The influence of socioeconomic characteristics, land use and travel time considerations on mode choice for medium and longer-distance trips. Journal of Transport Geography, 14(5), 327 –341. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2005.06.004

Loukopoulos, P., & Gärling, T. (2005). Are Car Users Too Lazy to Walk?: The Relationship of Distance Thresholds for Driving to the Perceived Effort of Walking. Transportation Research Record, 1926(1), 206–211. doi: 10.3141/1926-24

Mackett, R. L. (2002). Increasing car dependency of children: should we be worried? Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Municipal Engineer, 151(1), 29–38. doi: 10.1680/muen.2002.151.1.29

Mackett, R. L. (2014). The health implications of inequalities in travel. Journal of Transport & Health, 1, 202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jth.2014.07.002

Mahadevia, D., & Advani, D. (2016). Gender differentials in travel pattern - The case of a mid-sized city, Rajkot, India. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 44(February), 292–302. doi: 10.1016/j.trd.2016.01.002

Matthies, E., Kuhn, S., & Klockner, C. A. (2002). Travel Mode Choice of Women: The Result of Limitation, Ecological Norm, or Weak Habit? Environment and Behavior, 34(2), 163–177. doi: 10.1177/0013916502034002001

McGuckin, N., & Srinivasan, N. (2005). The Journey-to-Work in the Context of Daily Travel. In Presented for the Census Data for Transportation Planning Conference, Transportation Research Board. Irvine, California. Retrieved from http://www.travelbehavior.us/documents/5.pdf

Miralles-Guasch, C., Avellaneda, P. G., & Cebollada i Frontera, A. (2001). Los condicionantes de la movilidad en un nodo de la ciudad metropolitana: el caso de la universitat autònoma de Barcelona. Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. [ Links ]

Miralles-Guasch, C., & Domene, E. (2010). Sustainable transport challenges in a suburban university: The case of the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Transport Policy, 17, 454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.04.012

Miralles-Guasch, C., Martinez-Melo, M., & Marquet, O. (2014). On user perception of private transport in Barcelona Metropolitan area: an experience in an academic suburban space. Journal of Transport Geography, 36, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.02.009

Miralles-Guasch, C., Melo, M. M., & Marquet, O. (2015). A gender analysis of everyday mobility in urban and rural territories: from challenges to sustainability. Gender, Place & Culture, 23(3), 398–417. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2015.1013448

Mitra, R., Siva, H., & Kehler, M. (2015). Walk-friendly suburbs for older adults? Exploring the enablers and barriers to walking in a large suburban municipality in Canada. Journal of Aging Studies, 35, 10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.07.002

Motte-Baumvol, B., Bonin, O., & Belton-Chevallier, L. (2017). Who escort children: mum or dad? Exploring gender differences in escorting mobility among parisian dual earner couples. Transportation, 44, 139–157. doi: 10.1007/s11116-015-9630-1

Noack, E. (2011). Are Rural Women Mobility Deprived? - A Case Study from Scotland. Sociologia Ruralis, 51(1), 79–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00527.x

Oakil, A. T. M., Nijland, L., & Dijst, M. (2016). Rush hour commuting in the Netherlands: Gender-specific household activities and personal attitudes towards responsibility sharing. Travel Behaviour and Society, 4, 79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tbs.2015.10.003

Pérez, R., & Capron, G. (2018). Movilidad cotidiana, dinámicas familiares y roles de género: análisis del uso del automóvil en una metrópoli latinoamericana [Daily mobility, family dynamics and gender roles: analysis of car use in a Latin American metropolis]. QUID, 16(10), 102–128.

Peters, D. (2013). Gender and Sustainable Urban Mobility. Thematic study prepared for Global Report on Human Settlements 2013. Retrieved from http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2013 [ Links ]

Pitombo, C. S., Kawamoto, E., & Sousa, A. J. (2011). An exploratory analysis of relationships between socioeconomic, land use, activity participation variables and travel patterns. Transport Policy, 18(2), 347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.10.010

Plaut, P. O. (2006). The intra-household choices regarding commuting and housing. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 40, 561–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2005.10.001

Polk, M. (2003). Are women potentially more accommodating than men to a sustainable transportation system in Sweden? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 8(2), 75–95. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9209(02)00034-2

Queirós, M., & Marques de Costa, N. (Eds.). (2012). Gender Dimensions of Transportation in Portugal. Dialogue and Universalism Journal, 3(1), 47–69.

Rau, H., & Manton, R. (2016). Life events and mobility milestones: Advances in mobility biography theory and research. Journal of Transport Geography, 52, 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.02.010

Ravalet, E., Vincent-Geslin, S., & Dubois, Y. (2016). Job-related “high mobility” in times of economic crisis: Analysis from four European countries. Journal of Urban Affairs, 39(4), 563-580. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2016.1251170

Roberts, J., Hodgson, R., & Dolan, P. (2011). “It’s driving her mad”: Gender differences in the effects of commuting on psychological health. Journal of Health Economics, 30(5), 1064–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.07.006

Rodríguez Moya, J. M., & García-Palomares, J. C. (2012). Diversidad de género en la movilidad cotidiana en la comunidad de madrid [Gender diversity in daily mobility in the community of madrid]. Boletín de La Asociaci ón de Geógrafos Españoles, 58, 105–132.

Root, A., & Schinder, L. (1999a). Women, motorization and the environment. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 4, 353–355. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9209(99)00012-7

Root, A., & Schinder, L. (1999b). Women, motorization and the environment. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 4(5), 353–355. doi: 10.1016/S1361-9209(99)00012-7

Rosenbloom, S. (1989). Trip chaining behaviour: a comparative and cross cultural analysis of the travel patterns of working mothers, gender. In M. Grieco, L. Pickup & R. Whipp (Eds.), Transport and Employment: the Impact of Travel Constraints (pp. 75-87). Avebury: Aldershot. [ Links ]

Rosenbloom, S., & Burns, E. (1994). Why Working Women Drive Alone: Implications for Travel Reduction Programs. Transportation Research Record, 1459(274), 39–45.

Rozas Balbontín, P., & Salazar Arredondo, L. (2015). Violencia de género en el transporte público. Una regulación pendiente. Serie Recursos Naturales e Infraestructura [Gender violence in public transport. A pending regulation. Natural Resources and Infrastructure Series]. Santiago de Chile: Cepal. Retrieved from https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/38862/S1500626_es.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [ Links ]

Sánchez de Madariaga, I. (2013). The mobility of care. Introducing new concepts in Urban Transport. In I. S. Madariaga (Ed.), Fair shared cities. The impact of gender planning in Europe (pp. 49–69). Aldershot-Nueva York: Ashgate.

Sandow, E. (2008). Commuting behaviour in sparsely populated areas: evidence from northern Sweden. Journal of Transport Geography, 16, 14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2007.04.004

Sattlegger, L., & Rau, H. (2016). Carlessness in a carâcentric world: A reconstructive approach to qualitative mobility biographies research. Journal of Transport Geography, 53, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.04.003

Sayer, L. (2010). Trends in Housework. In Dividing the Domestic: Men, Women, and Household Work in Cross-National Perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press. doi: 10.11126/stanford/9780804763578.001.0001

Scheiner, J. (2014). Gendered key events in the life course: Effects on changes in travel mode choice over time. Journal of Transport Geography, 37, 47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.04.007

Scheiner, J., & Holz-Rau, C. (2012). Gendered travel mode choice: a focus on car deficient households. Journal of Transport Geography, 24, 250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.02.011

Schleith, D., & Horner, M. (2014). Commuting, Job Clusters, and Travel Burdens. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2452, 19–27. doi: 10.3141/2452-03

Schneider, R. J. (2013). Theory of routine mode choice decisions: An operational framework to increase sustainable transportation. Transport Policy, 25, 128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.10.007

Solá, A. G. (2016). Constructing work travel inequalities: The role of household gender contracts. Journal of Transport Geography Journal, 53, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.04.007

Stanfors, M. (2015). Family Life on the Fast Track? Gender and Work–Family Tradeoffs Among Highly Educated Professionals: A Cross-Cultural Exploration. In M. J. Mills (Ed.), Gender and the Work Family Experience (pp. 329–350). New York: Springer.

Vale, D. S. (2013). Does commuting time tolerance impede sustainable urban mobility? Analysing the impacts on commuting behaviour as a result of workplace relocation to a mixed-use centre in Lisbon. Journal of Transport Geography Journal, 32 , 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2013.08.003

Vance, C., & Peistrup, M. (2012). She’s got a ticket to ride: Gender and public transit passes. Transportation, 39(6), 1105–1119. doi: 10.1007/s11116-011-9381-6

Vega, A., & Reynolds-Feighan, A. (2009). A methodological framework for the study of residential location and travel-to-work mode choice under central and suburban employment destination patterns. Transportation Research Part A, 43, 401 –419.

Wedel, M., & Kamakura, W. A. (1998). Market Segmentationâ¯: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Wheatley, D. (2014). Travel-to-work and subjective well-being: A study of UK dual career households. Journal of Transport Geography, 39, 187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.07.009

Recebido: dezembro 2018. Aceite: fevereiro 2019.