I. Introduction

The focus of this research are the narratives around tourism gentrification and urban shrinkage, by elite stakeholders of the city of Porto. The general objective of the work is to analyse the political, entrepreneurial and academic discourse about these two phenomena by conducting individual interviews. Bearing this in mind, our initial proposition is the existence of an interaction between the population decrease and the tourist pressure resultant from the growing number of visitors in recent years. We consider that it is possible to deconstruct the existence of a common story articulated in a transversal and complementary way. We suggest that this discourse is based on two fundamental premises that we analyse critically. First, it is questioned that an unacknowledged loss of population entails some degree of social, economic, or environmental harm for the municipality of Porto and its residents. Second, the negative effects derived from the tourist flows are relativized, especially with regard to the socioeconomic transformation of the historic center and the proliferation of gentrification phenomena.

We begin this research with a review of the literature on the processes of gentrification and touristification based on an urban shrinkage phenomenon in section II. In section III, we present some useful facts about the city of Porto in this respect. In the following section, section IV, we explain in detail the methodological construction of our research. In the sections V and VI, we develop a critical analysis of the interviews based on two central questions. Firstly, we address the views of the interviewees regarding the loss of population in Porto and the phenomenon of urban shrinkage. Secondly, we analyze their narrative about the possible existence of a gentrification phenomenon in the historic center of the city. In both cases, always highlighting the role that tourism plays. Finally, in section VII, we develop a section where we discuss the conclusions drawn from this research.

II. Brief literature review

As urban shrinkage takes its place alongside urban growth, not only in theory but also in practice, local decision makers and practitioners, more or less prone to recognize shrinkage, have nevertheless to deal with its challenging consequences, at the very least, and find solutions for them (Ryan, 2019; Sousa & Pinho, 2015). Tourism, which links global and local processes (Teo & Li, 2003), is often a key development strategy, especially in cities that, despite population loss, economic decline and a certain degree of urban degradation, still possess one or more appealing existing or potential inherent qualities to attract world visitors. In shrinking cities, although it increases the number of city users, which includes very diverse groups as, for example, visitors or international students, it seldom increases the number of permanent residents. This solution is not without its social, spatial and economic impacts and, if taken to the extreme, the cure can turn into an illness itself and worsen not only population decrease but also the city’s liveability and the tourists’ experience as well (Herrera et al., 2007; Prytherch & Boira, 2009).

Gentrification and touristification are revealed as two sides of the same coin. However, they are not the same phenomenon. On the one hand, gentrification is understood as the process by which traditional neighbourhoods experience the arrival of social groups with a higher economic and cultural level that transform the area, increase the price of land, and end up displacing the most vulnerable neighbours. Frequently, the arrival of groups with high purchasing power is accompanied by a whole complex set of economic and financial actors: transnational capital, investors and real estate developers, small private owners and web platforms for short-vacation rentals as Airbnb (Wachsmuth & Weisler, 2018). There is a commercial dimension to gentrification whereby traditional local shops are displaced by the opening of establishments geared towards the new wealthy residents or tourism (Hubbard, 2018).

On the other hand, touristification (Lanfant, 1994) refers to the increasing pressure that global tourism places on different dimensions of the city. The term expresses how in some areas, tourism has reshuffled aspects such as the commercial and residential offer, infrastructures and services, or urban planning, according to the needs of tourism to the detriment of the resident population. Despite being two processes that may appear interwoven, touristification does not lead to the substitution of the original population for a more affluent one. Although, at first, it involves gentrification, as the most vulnerable are the first to be pushed away. The final consequences of touristification are displacing the entire population to commodify space and make it profitable. Therefore, both processes accelerate the demographic and urban shrinkage trends by creating socially and demographically empty spaces in the city. In such settings, the separate logics and causes of gentrification and touristification - the process of a tourism - and tourist-based transformation of urban environments - begin to blur, one cultivating the other, and sharing the transformation of land and property markets, the general voluntary or coerced displacement of former residents and the key role played in this transformation by State policy and capital investment (Hackworth, 2002; Hackworth & Smith, 2001; Sequera & Nofre, 2018).

Researchers began to take an interest in tourism as a central element in global, national, and urban economies in the 1980s, and as urban tourism grew over the past decades also did the connection between the two (Freytag & Bauder, 2018; Herrera et al., 2007). However, the interplay between urban tourism and urban transformation was considered neglected until very recently (Ashworth & Page, 2011). All over the world, low-cost airline carriers and peer-to-peer online property rental platforms have promoted leisure mobility (Hooper, 2015). Sequera and Nofre (2018) explain the most recent upsurge of tourist influx in the largest cities of southern Europe with: i) the growing geopolitical instability in otherwise popular tourist destinations (e.g., Egypt and some countries of the Maghreb and the Middle East; ii) the volatility of financial markets against the safety of investments in real estate; and iii) the economic crisis, between 2008 and 2016, and the pursuit for an easy way out of it. In turn, in historic centres, the approach to heritage recovery becomes increasingly business-like as they turn into new destinations for mass tourism (González-Pérez, 2019) and buy-to-let (BTL) gentrification phenomena spread (Paccoud, 2016). The contradiction is that while cities dedicate themselves to tourist-oriented development in the effort to capture revenues they run the risk of diluting the geographical distinctiveness that made them attractive in the first place (Herrera et al., 2007; Judd & Fainstein, 1999; Sequera et al., 2018).

Research emphasises not only the negative aspects of tourism, and more recently intense touristification processes, and overtourism, but also the lack of tools to tackle them (Del Romero Renau, 2018; Koens et al., 2018; Perkumienė & Pranskūnienė, 2019). For Sequera and Nofre (2018), touristification is characterized by cross-class displacement, class diversity, Disneyfication, depopulation, worsening of community liveability, transnational and local real estate market, risk investment funds and private owners, and last but not least temporary accommodation. Although not a new phenomenon, today, overtourism is one the most trendy expressions to describe the negative impacts attributed to tourism, and occurs when a destination receives more tourists than it can handle (Koens et al., 2018; Perkumienė & Pranskūnienė, 2019). Impacts range from the overcrowding of infrastructure, facilities and commercial activities to the relegation of resident population (Peeters et al., 2018). McKinsey (2017), the World Tourism Organization (United Nations World Tourism Organization [UNWTO], 2018), and the European Parliament (Peeters et al., 2018) published reports concerning overtourism and how to deal with it, that emphasize the importance of a local outlook on this phenomenon. In shrinking cities, gentrification or localized reinvestment have generated confidence that they can become boom towns once more (Ehrenfeucht & Nelson, 2018), as they transition into prosperous shrinking cities, a new notion advanced by Hartt (2019).

III. Some facts about the city of Porto

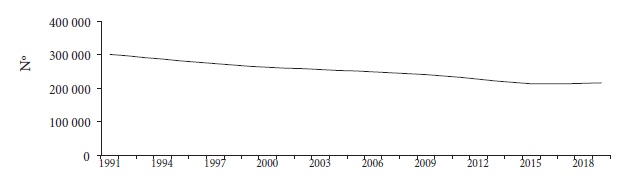

This is the case of Porto, that has developed a negative demographic trend over the past 50 years (Carrilho & Craveiro, 2015), especially in the city centre. However, this decreasing tendency turned in 2017, when the city began to gain residents (fig. 1). Therefore, everything seems to indicate that we have reached a turning point regarding the historical pattern of urban and demographic shrinkage. The city has become an excellent laboratory to observe how the traditional sociological background interacts with dynamics encouraged by the new engineering of urban space production and economic accumulation. The revaluation of its built and intangible heritage, the design of a brand image associated with culture and leisure, and the resulting explosion of urban tourism, have put Porto under the same level of tourist pressure as other European cities such as Lisbon, Barcelona, or Venice. In the last decade, the number of tourist accommodation establishments increased more than 205%, considerably expanding the accommodation capacity. In 2018, the number of guests almost reached two million (1 996 461 guests), of which more than 1.5 million were foreigners (Instituto Nacional de Estatística [INE], 2018). Early indicators of this process had already been noticed by Rio Fernandes and Chamusca (2014). Thus, recent gentrification processes in Porto comprehend touristification, as well as studentification (Carvalho et al., 2019).

Source: National Institute of Statistics (INE)

Fig. 1 Evolution of the population of Porto (1991-2019)

Porto, the second most populous city in Portugal after the capital, with just over 216 000 residents in 2019 (INE), is a medium-size city for European standards, thus the tourism pressure and the arrival of foreign capital have a greater impact in relative terms (as well as the potential negative consequences of these processes). Moreover, compared to other European cases, the economic and social transformation of the city has occurred in a fairly short period of time. Although it was a process in which many factors converged, we can establish flashing points such as the recognition of the historic center as UNESCO World Heritage Site (1996), the distinction of Porto as European Capital of Culture (2001) and the expansion of the Sá Carneiro airport (2007) for the tourist boom in the city. This dizzying increase of tourism and foreign investment contrasts with the sociodemographic reality characterized by structural resident population loss and ageing. The degradation of the historic centre and other core parts of the city, the emergence of new lifestyle standards during the 1980s and the 1990s, accompanied by real estate development in the neighbouring municipalities and later the construction and expansion of the metro network are some of the factors that can explain this downward trend. Today, high housing prices and buy-to-let gentrification in Porto prevent people from returning, as the city remains a prime example of a shrinking city in Portugal and in Europe. According to Cardoso and Silva (2018), based in a quantitative survey, at least the majority of those who remain in Porto consider the overall impact of tourism to be beneficial, bringing economic benefits and supporting social and cultural development of the city.

As a reference for the analysis, additional information about Porto will be given or revisited in the beginning of parts II and III, as well as appear intertwined with the text.

IV. Methodology

This research focuses on Porto as a case study, because it enables an in-depth analysis of multidimensional phenomena such as urban shrinkage (Ročak et al., 2016). The city of Porto is a paradigmatic case. First, for being a medium-sized city in the European urban system. Second, due to the enormous tourist pressure in the historic centre in recent years. Third, for constituting a shrinking city with structural population loss in the last half century. For these reasons, and because of its direct consequences on issues such as housing, public space, mobility, and commerce, we seek to analyse the opinion of different political, economic, and academic stakeholders. Our aim is to analyse the discourse that deals with the phenomenon of tourism in a shrinking city, from the point of view of main elite socioeconomic actors. As a central hypothesis, we suggest that there is a general narrative that, with different nuances, is shared and assumed by the institutional, entrepreneurial, and academic elites in relation to the impact of tourism in the city of Porto and its role as a transforming agent in the framework of a process of shrinkage. Therefore, this is not a quantitative assessment of the consequences of tourism in Porto and its relation to the structural population decline, but an analysis of the narrative that key stakeholders develop around it. This is an eminently exploratory and critical work which combines political discourse, academic criticism, and economic approach.

Unlike other traditional quantitative research on this subject, we try to promote a different line of research - narrative research - a mode of inquiry used by a varied number of disciplines. In this specific case, narrative research aims to explore and conceptualize the meanings that elite stakeholders assign to urban shrinkage and (tourist-led) gentrification phenomena in Porto. Working with a small sample of participants makes it possible to obtain diverse and wide-ranging discourse. Also important is the fact that narratives are “not an objective reconstruction of life [they are] a rendition of how life is perceived” (Webster & Mertova, p. 3), which takes a whole new meaning when investigating the implications of the story(ies) told by elite stakeholders in Porto. If the stories do not match the facts, evidence based planning and urban policy loses strength as facts get diluted by the narrative, which means complex urban problems may not be addressed to the point. Analysing the rich discourse of the stakeholders helps to understand the logic of the socio-urban phenomena. We propose that is possible to identify crosscutting aspects, allowing to structure a general narrative that explains public policies and private initiatives developed so far in relation to urban management and urban services, as well as outlining likely medium-term measures in this regard. We also consider that this methodological approach can be extrapolated to other urban realities regardless of the composition and fields of the actors at stake. Thus, the search for new approaches to analytically address issues such as the socio-economic redistribution of a city as a result of a complex relationship between tourism, gentrification and shrinkage, can stimulate its study in other territories.

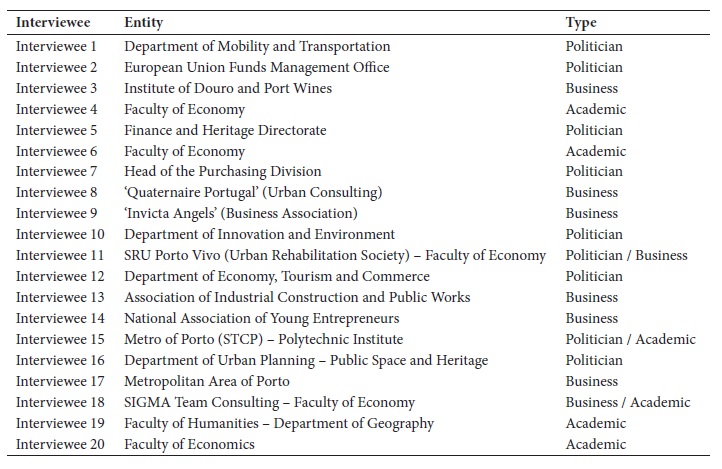

In order to verify the considerations and research questions pointed out, we opted to use qualitative research method, namely individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews with twenty elite stakeholders from the political, entrepreneurial and academic spheres of the city of Porto and explore their views on these same questions. Initially, fifty potential stakeholders were contacted, and twenty agreed to participate (Appendix 1). It is necessary to point out that, within the academic community, professors from different disciplines were initially contacted. However, there is an overrepresentation of the world of economics, in any case, without premeditation. It is also pertinent to highlight that some of the political stakeholders were elected, while others belonged to the technical staff. The interviews took place over a period of three months and were carried out on the premises of the city hall of Porto, several corporate and institutional headquarters, and the Faculties of Engineering (FEUP), Economics (FEP) and Humanities (FLUP) of the University of Porto.

The design of the interviews with the stakeholders was carried out taking into account the characteristics of the interviewees and the two major issues that structured our research: 1) to define the main characteristics of the process of urban shrinkage in the municipality of Porto, identifying triggering factors and possible consequences, and 2) to understand the role that phenomena such as gentrification and tourism play in urban shrinkage. The interviews lasted around 45 minutes. The interviewer began with a set of initial questions to be answered by the stakeholders in order to frame a debate on the demographic shrinkage in the municipality of Porto and their opinion on the phenomena of gentrification and touristification. The preliminary questions, the same for all interested parties, were the following:

In your opinion, is there an urban shrinkage process in Porto?

To what extent do you consider that the process of urban shrinkage affects the public services and infrastructures of the city?

To what extent do you consider that the loss of population affects the city’s economy and shapes the design of the municipal budget?

To what extent do you consider that this process of urban shrinkage can generate new socio-economic inequalities or increase existing ones?

Is there any type of political initiative developed in recent years that you consider relevant to mitigate the effects of urban shrinkage in Porto? How would you evaluate the result?

Can we talk about a phenomenon of touristification in the historic centre?

What is in your opinion the relationship between tourism and urban shrinkage?

What role does housing (and tourist accommodation housing) play?

Can we talk about a phenomenon of gentrification in the historic centre?

How do these three processes interrelate: touristification, gentrification and urban shrinkage?

Subsequently, and depending on the stakeholder’s work activity, the interview focused on specific aspects related to issues such as urban planning, mobility, finances, or Porto’s socioeconomic structure. The interviews were planned to cover the entire urban complex of the city of Porto, however, due to the nature of the processes in question (tourism and gentrification), the interviewees focused primarily on the historic center (except for the references made to the eastern part of the city). That is why, in spatial terms, the historic center has a special relevance and prominence. Additional questions were asked whenever there was a need to explain or develop certain issues. Topics such as tourism, housing, public space, and the transformation of the historic centre of Porto were a constant in all interviews, always framed within the context of a strong loss of resident population.

V. Discourse on population loss and urban shrinkage

As mentioned earlier, Porto has experienced a structural population loss since the early 1980s. When asked about this negative pattern, some of the interviewees highlighted the demographic turnaround that took place in 2017. Several stakeholders, mainly from the field of politics, predicted that this trend twist will continue soon. Tourism as a social, economic and entertainment engine, in addition to an adequate housing policy, would be, in their opinion, the main keys to explain this change in trend and the attraction of new residents.

In fact, despite this positive change and the slight increase in residents in recent years, there are areas, such as the historic areas of the city, that have been demographically bled out for years. In these areas, population decreased from 20 342 to 9334 inhabitants, between 1991 and 2011. They lost about half of the total resident population, approximately 11 000 individuals in just 20 years (Alves, 2017). In this context, we wanted to question stakeholders about what, in their opinion, are the keys that explain this shrinkage process, as well as the recent increase in residents, and what are the implications that this process has for the city.

The first aspect that stands out from the stakeholders’ stories, in a general way, is the necessity to approach Porto at a metropolitan level. Interviewees argued that, to spatially read Porto, one must zoom out to the metropolitan scale and Porto must be inserted in this territorial context. Thus, stakeholders mostly emphasized the role played by Porto in the metropolitan area and pointed out that the loss of residents should be relativized since it did not mean a loss of centrality. They suggested quite the contrary, because the metropolitan area had been growing, implying that many former residents had moved to neighbouring municipalities, while Porto continued to act as an economic, labour, social and cultural centre.

The inhabitant of Porto does not know where his municipality ends and where another begins. For him, the metropolitan area is all the same (…). The extension of the periphery of Porto is completely integrated into the urban grid of the remaining municipalities. (Int. 12i)

(…) there is a set of services that have to be managed and planned at the metropolitan level, so I look at that level and I would say that the shrinkage of the population in the municipality itself is not a particularly relevant issue having a metropolitan planning level. (Int. 6)

Recently, population decrease was accompanied by a remarkable increase of tourism in the city. The three groups of interviewees believed that firstly tourism, and secondly foreign investment, offset resident population loss in a certain way, both in demographic and financial terms. However, the confluence of users put great pressure on the municipality’s infrastructures and collective services, for example: public transports, road infrastructure, car parks, city maintenance and cleaning, urban safety, etc. Therefore, some political and academic interviewees denounced that municipal coffers must bear the costs derived from this centrality without necessarily receiving suitable economic compensation.

(…) as Porto lost population, but did not lose centrality in terms of employment, there is a very large number of people who come to Porto every day to work. And, therefore, there is a lot of pressure on the infrastructure of Porto (…) with negative effects on the city budget without it having the corresponding income. (Int. 10)

For this reason, the interviewees, especially those from the political sphere, drew attention to the importance that measures such as the “tourist fee”, a levy charged per person and per night, has to reverse, to some extent, the impact that tourism pressure exerts on municipal infrastructures and services, and consequently on the municipal budget. Ergo, they argue this fee mitigates obsolescence in view of the structural resident loss.

For example, initially we have waste disposal and collection system set up for X residents. However, the number of users can increase brutally, for example, double or triple. If this happens, it places a lot of pressure on the system. For this reason, the municipality of Porto had to introduce the tourist fee. The tourist fee is a response to this economic dimension that surpasses us, that we cannot accommodate, that puts pressure on our infrastructures, and that we say, ok, we are going to have to fix it with some mechanism that helps the infrastructure system serve those who live and work here in the city. (Int. 9)

In any case, there was a dominant argument that municipal infrastructures and services were not underutilized or obsolete due to resident loss because it did not translate into fewer city users. Quite the opposite, they should be expanded in the face of tourist pressure and metropolitan centrality. As soon as interviewees were asked about causes, all of them highlighted the high housing prices and rents, pushing population to adjacent municipalities. Nonetheless, chiefly institutional stakeholders stressed that their connection with the core city remained a determining factor in their daily routines.

I think the city (...) was turning into a desert with population contraction, and now it is being populated by people who do not stay, who are tourists. (…). And, perhaps, now the dynamism that the city presents attracts the people that until now had been pushed away. However, there is the phenomenon of higher housing cost due to urban pressure. (…) The same houses that were abandoned and that were in a state of conservation already very deteriorated are now rehabilitated, (…) but the prices are no longer so attractive and, therefore, it will not be easy to attract people. (Int. 8)

It is possible to differentiate two fundamental areas where stakeholders advocate that public policies should be focused in order to minimize impacts of urban shrinkage and more efficiently manage municipal infrastructures and services. First, private sector’ interviewees and, with greater emphasis, academics pointed out the need to provide better housing conditions. In some cases, they talked about affordable housing and in other cases directly of social housing.

However, to a certain extent, the first group undermined this phenomenon and framed it within a process of redefinition of the city and its external image; therefore, assuming that the difficulty of getting affordable housing is a positive indicator of economic strength and attractiveness in any city. In addition, this group pointed out that the local government had developed specific mitigating housing policies to slowdown increase in housing prices.

On the contrary, academics depicted a more critical picture, considering that lack of affordable housing is the main cause of the population exodus to neighbouring municipalities. In this sense, the academics interviewed criticized the lack of housing policies that facilitated access to property in the city of Porto. Likewise, they highlighted the pernicious consequences that unregulated tourism entails in terms of housing and consumption in the city.

In sum, the entrepreneurial and academic sectors pointed out that the lack of affordable housing was the main trigger for population flight, although from a different perspective. Consequently, when questioned about measures or initiatives that could pull population into the city, both groups more or less emphasized the importance of a new housing policy congruous with the current context. In this regard, the most important municipal initiative highlighted was the significant budgetary effort aimed at housing renewal in the historic centre and downtown, as a strategy both to mitigate price escalation and to physically compact the city, thus adapting to the current scenario.

Therefore, so that there is a more diversified composition of the population of Porto, what is healthy, and so as not to push families and people of lower income from the city, a social housing policy, for me, is an absolute priority. It does not have to focus in working-class neighbourhoods, it can be a set of incentives for housing renewal, with financial support to ensure that it is affordable to low-income families. This is the great challenge for me. It is what is on the front line of the challenges and the answers that the municipal services must develop and come up with in the city of Porto. (Int. 15)

And, therefore, the Municipalities and the State have tried to put into action what they call an “affordable lease program”, but I do not know if they will get it. I do not know if they are going to get it because there is no lack of houses in the market. There are many houses. But, in fact, they are in very bad condition and the owners are not going to rehabilitate them because they are not in attractive and valued areas for the market, and therefore this goes with a significant public investment and, on the other hand, the pressure on the housing and on the stores is in such a big way that at this time the prices went up and up all over the city, not only in the centre. (Int. 14)

Political interviewees also mentioned housing as a fundamental issue to understand the population mobility flows that Porto has experienced. All interviewees made a point of praising the work of the municipality in improving housing affordability.

A program was launched to make housing affordable. It is not social housing, because the municipality already has a percentage (...) that is much higher than the national and European averages. There really is a lot of municipal housing for a population that needs housing at controlled costs. Now, the local government intends to launch a program for housing construction at affordable costs. It does not mean that it is at controlled costs. It is affordable. (Int. 5)

What I know is that there is some concern with social housing (...). Some investments have been made. I also know that for some years there has been a concern with urban rehabilitation. It was an important issue and there was a huge investment, even with European funding, for a very noteworthy set of projects very much focused on the historical area of the city. (Int. 13)

However, from a political standpoint, in addition to public housing, the need to strengthen other attractiveness factors was introduced. Thus, reference to public investment under the seal of the Strategic Masterplan of the Eastern Area of Porto was a constant repeated by many of the interviewees, as a contributor to territorial cohesion. Stakeholders asserted that they expected public investment in this area, especially in transport and mobility, to act as an economic engine, revitalising the area, attracting private capital, compacting urban elements and attracting population to the area (e.g., the future intermodal terminal in Campanhã).

Also interesting was the incorporation of a new variable to the discourse on urban shrinkage. From the institutional point of view, emphasis was given to the importance that the cultural dimension has had in the reconstruction of the image of the city. Culture, also associated with consumption and leisure, constitutes the backbone of local urban policy, as well as an instrument of socio-spatial cohesion.

This is what we have invested more in. Culture unites society, because for people, whether we want it or not, culture is an important factor of social cohesion. (...) So if that is possible to create culture here, I think that the climate of shrinkage in the city can be turned around. Shrinkage must be overturned with quality of life. And to be able to achieve this, culture is essential. (Int. 9)

VI. Discourse on gentrification and transformation of the historic centre

The unceasing increase of visitors puts at risk the already precarious balance that exists between the tourist and the residential dimensions of Porto. The centrifugal mobility processes explained by the push of suburbanization, together with the proliferation of shopping malls on the fringe of the municipality, have shaped a donut-like morphology (Rio Fernandes, 2005) and a trail of buildings in decline, old and poor people and stagnant stores (Rio Fernandes et al., 2018). There are previous works that explain how gentrification is not a new phenomenon in Porto but has been reproduced cyclically over the decades (Pinto, 2014). Despite this fact, little data is available to quantify population redistributive movements. However, studies such as those of Pinto (2012) highlight the growth of creative activities in the historic centre.

In addition, it is risky to speak of a standard residential gentrification phenomenon, since many of the new residents, who returned to the centre from other municipalities, have rehabilitated empty and heavily rundown dwellings, which does not translate into a process of residents’ substitution. Consequently, contemporary drivers of gentrification may not just be patterns of residential change or the attraction of workers and creative industries. We must add the growing openness and appeal of the city to international users (tourists, students, and all kinds of visitors) as the main driver of gentrification in Porto (Rio Fernandes et al., 2018). In this sense, it is more accurate to note that Porto is facing a phenomenon of tourism gentrification (Gotham, 2005).

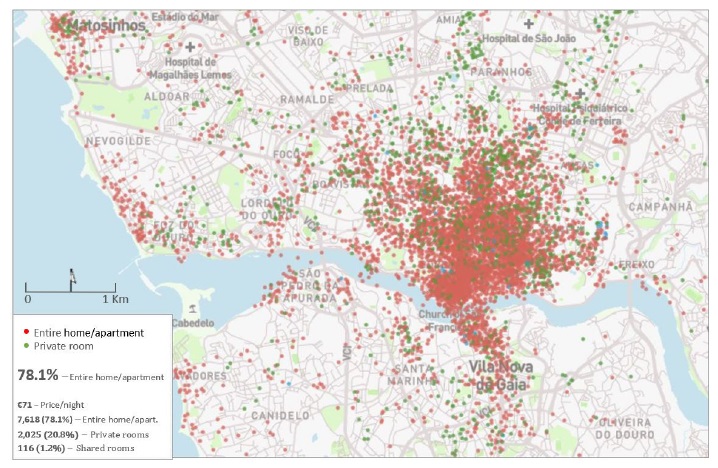

Thus, looking at indicators such as the evolution of tourist accommodation in platforms like Airbnb (fig. 2), we can see how Porto illustrates a model of fast growth of short-term, rental-driven urban tourism that fosters a context of income concentration and growing massification (Chamusca et al., 2019). Consequently, research carried out reveals how short-term rental tourist accommodation has increased the price of housing in the historic centres of cities such as Porto, reducing the supply of affordable housing and displacing low-income people (Franco et al., 2019). To the pressure of new users of the city (tourists, visitors, and students), the proliferation of vacation rental homes, the structural loss of population until just a few years ago and the rising cost of housing, we must add the change in the commercial network. Drawing on Alves (2017), we can fathom how there is a direct bearing between the commercial gentrification processes and the growing threat of residential flight from the historic centre. Altogether, these processes outline a phenomenon of tourist gentrification in the historic centre of Porto.

Source: http://insideairbnb.com/

Fig. 2 Location of holiday rental apartments on Airbnb (November, 2018). Colour figure available online.

At first, most of the interviewees assumed a positive vision about the radical transformation that the city, and particularly the historic centre, has undergone in recent years. According to the interviewees, several factors explained this visible transformation. Stakeholders mentioned that the expansion of the Airport Francisco Sá Carneiro and the operation of low-cost carriers in Porto meant greater international accessibility. This was accompanied by a reformulation of the brand image of the city, associated with heritage, culture, and leisure. Beside these main elements of tourist attraction, safety, quality of life and gastronomy were also highlighted.

Except for academics, who generally had a more critical view of the processes of transformation and social change in the city, the other two groups always responded positively with respect to tourism increase. Likewise, the strong arrival of foreign investment in the form of real estate capital was seen as unequivocal evidence of the city’s attractiveness and dynamic local economy. The request for licenses for hotels, guesthouses and restaurants in the historic centre/downtown was understood as a good indicator of the socioeconomic boom of Porto due to its opening to the outside world.

The academics also agreed that tourism was highly positive, but suggested, from the beginning, that it entailed certain perils and that it produced several harmful processes for the most vulnerable social groups. Regardless, all the interviewees emphasized the social, economic, and material improvement of the historic centre and the downtown area compared to a few years ago:

Fifteen years ago, people stopped believing in the city and left because the site did not offer quality of life. It was a “hole” where there were people at night (...). People did not go there after dark. (Int. 16)

Only when we directly asked the interviewees about possible negative effects of tourism and real estate speculation, did certain reluctance arise in terms of social sustainability, and some imbalances were recognized, especially by the political and entrepreneurial stakeholders. However, it is possible to discern different interpretations. Thus, interviewees from the private business sector, despite recognizing some imbalances or problems of a socioeconomic nature associated with tourism, assumed it as a natural process in a scenario of change such as the current one. Hence, they understood that the displacement of residents due to the increase in the price of land/housing in the city centre was a similar process to any city that achieves some degree of tourism attractiveness.

Questioned about the existence of a phenomenon of gentrification in the historic centre of Porto, interviewees from the entrepreneurial sector expressed divided opinions. However, all stakeholders considered that the transformation of the centre had implied a substantial improvement in all areas and, only marginally, a displacement of the most vulnerable groups being, as we have already stated, a process like to the ones observed in other European cities. Most of the participants considered that a few years ago the historic centre was deeply neglected. The main explanation given for this was the so-called “Rent Law”. This historic law froze the rental of numerous dwellings for decades, allowing tenants of low purchasing power to have very affordable rents for very long periods of time.

According to the interviewees, as a consequence and in the absence of economic incentive due to the low revenue owners obtained, dwellings were not refurbished over the years. In turn, this generated urban dereliction in the city. In a later stage, the descendants of the owners, faced with the lack of minimum material conditions, chose to move to more liveable areas of the city, or out of the metropolitan area. Therefore, barely any original residents could be displaced because, simply, they hardly existed. The vast majority of the dwellings were empty or abandoned, in an advanced state of neglect. This was the central argument of the stakeholders who denied the existence of a classic gentrification phenomenon in the historic centre and downtown of Porto.

Political stakeholders followed a similar rationale. The members of the local government, as well as of other municipal institutions, considered that it was not possible to speak accurately about gentrification in these areas. As entrepreneurial stakeholders claimed, there were barely any people living in the historic centre and, therefore, there was not process of displacement of those most vulnerable groups. The area, they said, was an unhospitable place before the arrival of real estate capital, an inadvisable place to go, with some degree of crime and violence problems.

In relation to the so-called process of gentrification in Porto: it does not exist in fact, because gentrification implies that there were people living there to begin with. But we did not have people here in the centre. (Int. 9)

In any case, unlike entrepreneurial stakeholders, some local government officials recognized the existence of gentrification processes limited to a well-defined geographical area (Ribeira and Baixa), produced in the same terms as in other international tourist destinations. Therefore, it was considered an undesirable but “controlled” gentrification phenomenon. Contrarily to private sector stakeholders, from the political standpoint it was argued that the local government made efforts in terms of housing policies to try to mitigate harmful effects derived from property revaluation.

A relevant issue raised has to do with the proliferation of short-term rentalsii, which along with online platforms such as “Airbnb”, have grown exponentially in recent years changing the dynamics of the traditional real estate market. The academics interviewed believed that this activity, on the one hand, allows many families to survive. Moreover, it gives a practical meaning to vacant second-generation homes, whose new owners moved, at some point, but maintained the inherited family properties.

A similar vision was shared by the other two groups, who said that short-term rentals and hotels coexisted due to the high tourist demand. The vast majority of stakeholders only acknowledged the need to control tourist flows and make adjustments in what concerns aspects such as mobility or accommodation, sometimes way ahead in the interview. In any case, they considered that, due to the importance of tourism revenues for the city, any sort of public intervention to regulate this fruitful activity should be reduced to a minimum.

A final aspect addressed were the changes in the retailscape, especially in the historic centre and downtown area. The entrepreneurial interviewees indicated that touristification of traditional proximity commerce was an economic push factor, and as such it was necessary to normalize its transformation, following closely the logic of the discourse about real estate gentrification. Municipal authorities argued that there was a program to protect traditional shops that, because of their importance in the history of the city, should be preserved against speculation. The most critical view was provided, again, by academics who considered that this trend obeys, as in real estate, to underlying speculative dynamics for which, they argue, a stronger municipal intervention would be advisable.

VII. Discussion and conclusions

By conducting a series of interviews with elite stakeholders from the entrepreneurial, political and academic sectors of Porto, we have demonstrated the existence of a common narrative, barely differentiated by nuances, about the process of urban shrinkage and its ensuing consequences. There are several conclusions that we can draw.

First, from decoding the interviews, it is possible to establish a link between tourism and urban shrinkage. Despite tourism not being the initial cause, all interviewees assume that, currently, both processes are different sides of the same coin and that, to some degree, the latter is explained by the former. This confirms our general objective. Nevertheless, the common discourse assumes that the increase in tourist flows in recent years translates into economic prosperity and social dynamism and that, therefore, this justifies and legitimizes the harmful consequences that may arise from it. The impact of population flight to other metropolitan municipalities, and the resultant commuting, in terms of infrastructure and services, is considered to be mitigated by economics inputs from tourism. Thus, from the construction of this positive image of tourism, pushing residents towards peripheral municipalities becomes natural due to the increase of housing prices and rents in the city. Moreover, we should call attention to the fact that interviews lay bare that the interviewees discuss gentrification without a clear grasp on the concept.

However, there are nuances in this interpretation. Most of the interviewees from the business community accept this process and celebrate it as a positive indicator of socio-economic dynamism. Accordingly, these are collateral consequences of Porto becoming fashionable. From this point of view, the sociological homogenization of the historical centre through the substitution of lower socio-economic groups by others with greater purchasing power, also leading to the transformation of local commerce, can become a desirable scenario in economic and business terms. The interviewees belonging to the academic sector have a more critical vision and suggest more regulation of tourism. We can place the institutional perspective somewhere in between these two poles. Similarly, the most positive tourism effect perceived by the participants in Cardoso and Silva’s (2018) study was the increasing number of businesses in the city, followed by increased liveliness. Overall, resident participants considered the impact of tourism to be beneficial, bringing important economic benefits and supporting the wider social and cultural development of the city (Cardoso & Silva, 2018).

In any case, from the three standpoints, and in line with Cardoso and Silva (2018), it is highlighted that the point of friction between tourism and urban shrinkage are higher housing prices and rents. In this regard, reference is made to the need to introduce more family housing at affordable prices in the market. Furthermore, some of the academic interviewees point out that more emphasis should be placed on housing renewal. From the political point of view, this deficit is also implicit, but other variables are incorporated for new resident attraction, such as the promotion and decentralization of culture or the improvement of mobility and accessibility in traditionally marginalized areas (e.g., eastern part of the city). Both measures, housing rehabilitation and introduction of affordable housing and reinvestment in the eastern part of the city, in addition to the tourist tax, seem to be the two most notable strategies to fight urban shrinkage and lessen the effects of tourism-led gentrification.

Paradoxically, despite assuming these shortcomings in terms of affordable housing, the proliferation of short-term rentals is seen as justified due to the enormous tourist demand. Some interviewees even suggest that there is still room to grow, and, in general, short-term rentals are understood as reboots for vacant dwellings, matching many households’ income. Residents’ perceptions described by Cardoso and Silva (2018) differ in this regard, as participants seem to think that the city has reached a tipping point.

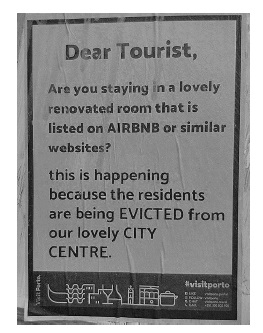

Finally, the construction of this common narrative about phenomena of socio-economic and spatial change in the city of Porto rejects, or assumes with great reluctance, the existence of a phenomenon of commercial and real estate gentrification in the historic centre of the city. As a result, the so-called “Rent Law”, which froze housing rents for decades, justifies the right of private capital to profitably capitalize on its property in the current context of tourism demand. In addition, the prior expulsion of a large percentage of tenants due to the extreme degradation and serious deficiencies of buildings - without the public administration assuming any degree of responsibility - would preclude talking about gentrification at the present time, as there are hardly any residents to push. This statement contrasts with citizen protests and signs of tension between residents and visitors that can be seen in the historic center (fig. 3).

In 2018, the mayor of Porto claimed that “Porto was always a gentrified city (...). But the worst gentrification was in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, when the city lost 150 000 inhabitants. (...). In 2007 or 2008 this was a ghost town. There was no cultural activity, the historic center was abandoned. It was like a donut. In the center there was nothing” (Rui Moreira, in La Voz de Galicia, January 21th 2018iii, authors’ translation). In these statements, the mayor directly names the population drain between 1970 and 1990 as gentrification, which was not the case, revealing, perhaps deliberately, a misconception of what gentrification means. The original population was not displaced. In fact, the ones who left were the ones who “could”, and no one replaced them for a long time. The mayor himself ends up denying the very existence of gentrification today: “The idea of gentrification is a boring idea of a reactionary Left that speaks more and more of a phenomenon that does not exist”. These statements support the main objective of this work: to confirm the existence of a mainstream narrative that, on one side, denies gentrification and urban shrinkage phenomena and, on the other side, relativizes or normalizes the negative consequences derived from tourist pressure.

This approach explains the tourism promotion policies based on the cultural dimension, the cornerstone of the government as highlighted in the interviews, not only as a factor of attraction, but as an invitation to settle in a liveable city: “I would like those who repopulate the city to be from Porto, but (…) the important thing is that the people who arrive are citizens who are fully integrated, who participate actively, who live here”. Thus, the mayor rejects the current idea of gentrification, although he uses it to explain the demographic shrinkage during the past decades and is committed to a model of tourist attraction that increases the number of residents. Moreover, culture is a key factor since it not only attracts visitors, but also symbolizes an exciting city to settle in. However, at no time does he discuss the increases in the rental price, the quality of life of traditional residents who still live in the center, their socio-economic structure, the transformation of commerce and the loss of the residential function of those areas gobbled up by short-term vacation apartments.

In short, the existence of a common approach to the phenomenon of demographic change and its relationship with the rise of tourism in the city of Porto is revealed through a biased and partial interpretation of the socio-spatial reality of the city. Local elites overtly encourage tourism as an omen of large unforeseen gains for local businesses, a lever for economic reinvestment in urban infrastructure and services, a source of jobs, and an impending generator of additional property fee revenue (Herrera et al., 2007). However, negative issues arising from the tourist impact, analysed in the works of Alves (2017), Carvalho et al. (2019), Chamusca and Rio Fernandes (2016), Rio Fernandes (2005), Rio Fernandes et al. (2018) or Silva (2010), are avoided or directly rejected. It should not be forgotten, in any case, that the opinions collected in the interviews do not necessarily represent all the political, business and academic stakeholders. There are critical voices, especially in the academic sphere, that reject this mainstream narrative.

This work was a critical and exploratory reflection on the discourse model that different elite stakeholders in Porto have about the relationship between urban shrinkage and tourism. The paper provides some clues in order to analyse other territorial contexts regardless of the final composition of their stakeholders and local factors. In this sense, we explored new ways of approaching joint analysis of complex urban phenomena in relation to public policies and the logic of private capital. As in other heritage cities, shrinking cities, and every city, policy and decision makers in Porto could benefit from a deeper understanding of residents’ perceptions of tourism (Muler Gonzalez et al., 2018), as well as those who live in neighbouring municipalities, increasing tourism value for the host community to help create a sustainable tourism activity and to promote and improve livability for all, in the future (Cardoso & Silva, 2018).

Finally, our findings show that although shrinking cities, like Porto, may thrive led by tourism, resultant gentrification is a real threat, despite being dismissed by the city elites, especially for the most vulnerable who can’t afford to leave the city but do not have enough money to stay. This dismissal is partially translated into current urban policy. As a result, the quest for prosperity and growth should be carefully equated with the costs for the quality of life of resident population and their right to the city. There needs to be a balance between the city’s elite narrative and the residents’ narrative.