I. Introduction

In 2013, Ukraine’s President Viktor Yanukovych was expected to sign EU-Ukraine Association Agreement that would strengthen ties between Ukraine and the European Union (EU). However, on 21 November he suspended negotiations on the association agreement with the EU. Instead of pursuing the country’s long‐held course towards European integration, Yanukovych decided to seek closer ties with the Russia‐led Eurasian Customs Union. This political shift provoked the social mobilisation of citizens who shared commitment to Western‐style democracy and supported the country’s integration with the EU. The demonstrators gathered at the Maidan, the square in the centre of Kyiv. The initially peaceful demonstrations, known as the Euromaidan protests (also called as Revolution of Dignity), triggered nationwide protests, and in Kyiv spiralled into violent interactions with numerous deaths, following the government’s decision to ban protests as well as intervene with heavily armed police (Kudelia, 2015).

The Euromaidan uprising in 2013 has not only mobilised masses in Ukraine but has also led to a strong reaction among the Ukrainian communities abroad. From the first days of the Euromaidan protests, the Ukrainian diasporas throughout the world supported the uprisings for democratic change.

While some literature exists about the Ukrainian diaspora participation in the (post)revolutionary process, few scholars focus on how the Euromaidan and the consequent war in Donbass fostered diaspora’s engagement and contribution to the homeland. Thus, the aim of this article is to explore how the Ukrainian diaspora was influenced by recent developments in Ukraine since November 2013.

Based on the results of a British Academy-funded research project on the Ukrainian diaspora mobilisation in the UK and Poland conducted in 2015-2016, the article discusses how the Euromaidan uprising in 2013 and the war that followed triggered a powerful wave of diasporic activities and thus a transnational social movement. This contribution examines two case studies of mobilisation of the Ukrainian diaspora, UK, and Poland, and focusses specifically on the interaction between mobilised old and new diaspora, the formation of a new Ukrainian “diasporic community”, the diaspora contribution to the homeland. The two cases, Poland and the UK, were selected because they are distinctly different in some important aspects. Poland has a long-established historical Ukrainian diaspora and has recently received large numbers of immigrants whereas it is comparably new and much smaller in the UK. It makes an interesting comparison.

II. Conceptual frameworks and methods

1. Theoretical accounts of diaspora and diaspora mobilisation

Diaspora is a blurred and contested concept; it means different things to different people at different points in time.

For the purpose of my study and in order to not miss out potentially relevant findings but to discover all diasporic or similar transnational activities, I apply a perspective of methodological cosmopolitanism, which allows to better perceive the complexity of the studied phenomena. Methodological cosmopolitanism, opposing to methodological nationalism (Wimmer & Glick Schiller, 2002), seems to be a more adequate attitude, because it does not expose the national point of view (Beck, 2004) and reduces the threat of essentialising. This puts the researcher in the trap of thinking about the studied groups as homogeneous, collective actors, and about their members as connected by shared values, ideas, and memories. In addition, methodological cosmopolitanism shifts the researchers’ view towards transcultural, transnational, translocal and global phenomena, which include migrations, diasporas, and multiculturalism policies. Thereby I include not only established diaspora but also new diaspora groups, notably migrants on temporary or permanent basis who left Ukraine from the 1991 onwards. Those yet still maintain ties to their homeland, developed a diasporic consciousness, and display diasporic practices and identities. This also enabled to explore the dynamic interaction and synergy effects of the different social groups with respect to their activities towards Ukraine as well as the adaptation of classical diasporas to some new realities, notably the fresh influx of contemporary immigrants.

In making this argument, I operate from Agunias’s and Newland’s broad definition of diaspora communities who view it as “emigrants and their descendants who live outside of the country of their birth or ancestry on temporary or permanent basis, yet still maintain affective and material ties to their countries of origin” (Agunias & Newland, 2012, p. 14).

Diaspora research has begun to move beyond classifying diasporas and their characteristics to look at how and why these groups emerge and dissipate (see Brubaker, 2005; Sökefeld, 2006). Diasporas are not fixed, pre-existing groups; instead, Steven Vertovec writes that diaspora identity “may be lost entirely, may ebb and flow, be hot or cold, switched on or off, remain active or dormant. The degree of attachment - and mobilisation around it - often depends upon events affecting the purported homeland” (Vertovec, 2005, p. 3).

Diverse frameworks and concepts have been deployed to explain the involvement of diaspora in politics in their home countries, from “long-distance nationalism” to “transnational activism” (Anderson, 1998). Diasporas can mobilise in radical ways by contributing financially to rebel factions, recruiting soldiers, and staging violent demonstrations (Collier & Hoeffler, 2000; Shain, 2002). They can also act moderately by staging peaceful protests and campaigns, lobbying, reframing conflict issues, supporting democratic factions, diffusing democratic ideas and practices, and participating in transitional justice initiatives (Koinova, 2011; Lyons, 2006; Young & Park 2009). According to Koinova (2015) “diaspora mobilisation” appoints individual and collective actions of identity-based social entrepreneurs who encourage migrants to behave in a way to make homeland-oriented claims, accomplish a political objective, or contribute to a cause. Brinkerhoff (2008) defines mobilisation as “purposive action”, and Müller-Funk (2016) outlines diaspora mobilisation as political activity, which crosses one or more borders. Mavroudi (2018) defines mobilisation in broad terms as “helping” the homeland in material ways, be it through small acts of charity or taking in part in demonstrations, to everyday advocating in favour of a cause.

Shain and Barth (2003) categorise members of diaspora into three groups:

Core members are the organising elites, intensively active in diasporic affairs and in a position to appeal for mobilisation of the larger diaspora;

Passive members are likely to be available for mobilisation when the active leadership calls upon them;

Silent members are a larger pool of people who are generally uninvolved in diasporic affairs but who may mobilise in times of crises.

They also distinguish between “active” and “passive” diasporas, with the former influencing host and homeland policies and the latter not. They argue that for active diasporas to be successful, they need motive, opportunity and means. Mobilisation is perceived as more likely to occur if it is identity reinforcing and where the right conditions occur in both the homeland and host country.

Al-Ali et al. (2001) introduced the distinction between actors’ capacities or abilities and their desires or willingness to engage in transnational activities. They suggest that capacity requires security of status, having an income above subsistence level, having the freedom to speak out, and developing social competences and political literacy - knowing how to lobby, campaign, speak in public, write leaflets, and so on. However, as I have shown elsewhere (Lapshyna, 2019) diasporic engagement is even found among irregular immigrants. This suggests that it does not necessary require security of status or income.

Recently, scholars have also used social movement theory to explain the emergence and trajectory of homeland-oriented activism of migrants and exiles (Adamson, 2012; Amarasingam, 2015; Fair, 2005; Koinova, 2009; Sökefeld, 2006; Wayland, 2004). In order to explain the dynamics of diaspora mobilisation scholars have focused on hostland political context and on homeland and international political opportunities (Koinova, 2011). Some social movement approaches offer insights into sustained mobilisation. Sustained mobilisation, even if moderate, could prevent dissolution of conflict-generated identities and create hubs of contentious activism (Beinin & Vairel, 2011). It can develop formal organisations or operate through informal social ties (Jasper, 2005). As I outline in my paper, by studying Ukrainian diaspora in two case studies we learn that it might take a different turn depending on the context in which they occur. Koinova (2015) also used a social movements approach to answer why some diasporas originating from the same homeland continue to mobilise in sustained ways during post-conflict reconstruction, while others do not. Baser and Swain (2010) agreed that the literature on social movements might help to analyse and explain diaspora activism in a more systematic way. However, the relation between diaspora actors and social movements requires more scholarly attention.

At the same time, Fiddian-Qasmiyeh (2013) pointed out that there is also a need to focus more on individual members of diasporas, rather than assume that those in diaspora act as a collective. This insight can be applied to the case of Ukrainian diaspora, which is very diverse and segmented, depending on the members’ skills, religion, class, age, initial migration motives, migration status and duration of stay in the host country.

Another important question is what drives diaspora mobilisation, what tends to encourage or hinder diasporic mobilisation? There is therefore a need to explore who is involved in diaspora mobilisation (Kleist, 2008; McConnell, 2015), as well as the assumptions made about identities, obligations and diasporic activities (Faist, 2008).

In recent years, scholarly interest on diasporas as important political actors that engage in homeland projects has grown. Although research on established diasporas continue to dominate the field, current theorising has started to examine the cases of modern diasporas such as Ukrainians, Albanians, and Mexicans and their struggles for democratisation, independence, and post-conflict recovery (Koinova, 2018; Pérez-Armendáriz, 2019; Pfutze, 2012; Tatar, 2020).

A literature survey in the Ukrainian diaspora revealed that history or culture are the dominant focus of diaspora studies. Satzewich (2002) traced 125 years of Ukrainian migration, from the economic migration at the end of the 19th century to the political migration during the inter-war period and throughout the 1960s and 1980s resulting from the troubled relationship between Russia and the Ukraine. He argues that the Ukrainian diaspora enhanced the process of democratisation, lobbied foreign governments to adopt pro-Ukrainian policies. It contributed financially to political parties’ advocating state independence.

A growing body of literature has begun to highlight the response of the Ukrainian diaspora to the Euromaidan movement. The role of Ukrainian diasporas in (post)revolutionary process has been studied by Melnyk et al. (2016), who in their research discussed the formation of a new Ukrainian “diasporic community” in Germany and Poland. Their work come to similar conclusion that civic engagement of Ukrainians in Germany for their home country has dramatically increased since the Maidan protests. The authors posed an interesting question whether these processes will result in a new sustainable “diasporic community” of Ukrainians in Germany. This question of sustainability of the Ukrainian diaspora engagement is also relevant for my research.

Others, such as Tatar (2020) have suggested that the Euromaidan and the war played an important role not only in mobilising diaspora communities in Canada but also in forming new advocacy strategies and increasing the political visibility of the Ukrainian diaspora. As I will show in this article, my findings on two other case studies confirm this argument.

The results from this study can be compared against other studies of the Ukrainian diasporic community in Poland and Canada. For example, Dunin-Wąsowicz and Fomina (2020) and Nikolko (2019) found that the Ukrainian crisis 2014-2015 was an unprecedented catalyst for Ukrainian diaspora mobilisations and subsequently the formation of Ukrainian diasporic civil society. This further solidified the bond between diaspora, homeland and produced a lasting effect. These findings are thus consistent with my research showing that the Euromaidan, the annexation of Crimea, and the war in Eastern Ukraine have inspired diasporans in Poland and the UK to become involved in the process of Ukraine’s democratisation.

However, in the general literature of diaspora, and in particular in the Ukrainian context, however, there has been a lack of theorising about Ukrainian diaspora mobilisation and the role of the Ukrainian diaspora in helping of the homeland. This article aims to address some of the research gaps.

It is important to explore the diasporic action (or inaction) at times of threshold events such as Euromaidan and the Russian aggression against Ukraine. Several questions arise, which my research seeks to address. How are competing theorisations and definitions of diaspora relevant to the Ukrainian diaspora? Are diaspora members compelled to act or to mobilise help for the homeland at a time of crisis? Are they willing and, more importantly, have the capacity to engage with helping the homeland? These questions guide my analysis of the Ukrainian diaspora in the UK and Poland facilitates discussion of diasporic mobilisation on the one hand and diaspora contribution to the homeland on the other.

2. Methodology

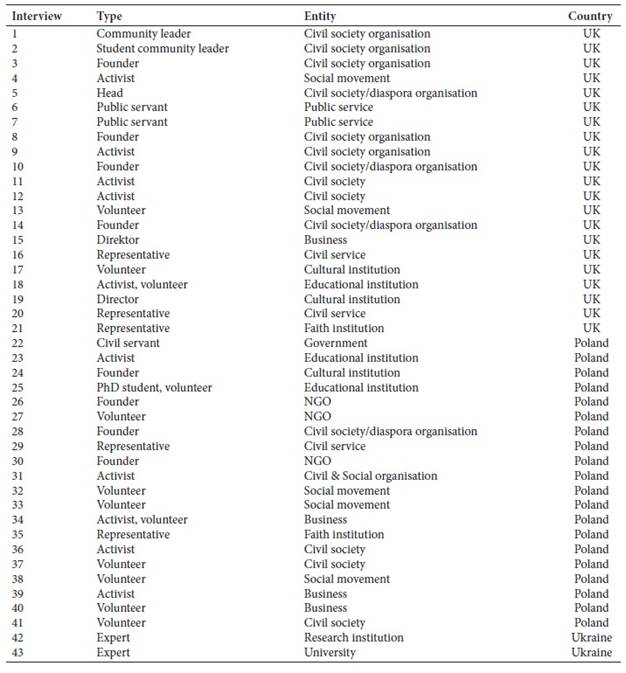

To address the above listed questions, this contribution is based on empirical data collected by the author in 2015-2016. It is based on the project: “Do diasporas matter? Exploring the potential role of diaspora in the UK and Poland in the reform and post-war reconstruction of Ukraine” which was funded by British Academy. I conducted 43 in-depth semi-structured interviews with diaspora and non-diaspora actors in the UK, Poland, and Ukraine. In addition, field observations and a literature survey were carried out. I have chosen Poland and the UK as two cases. These two case studies are interesting not only because of their similarities (both EU countries with economic and political stability and better income opportunities) but also because of their differences. Poland has a long-established historical Ukrainian diaspora and has recently received large numbers of Ukrainians (estimates vary from 0.5 to 1.25 million), whereas in the UK Ukrainian immigration is comparably new and also much smaller (estimates vary from 30 000 to 100 000). While acknowledging differences of case studies in terms of history, context, scale, characteristics of old and new diaspora, this project has shown that in the case of mobilisation they act similarlyii. A comparative analysis thus allows a systematic assessment of the diaspora mobilisations as a response to the Ukrainian crisis 2014-2015 in different contexts.

The interviews were conducted mostly in London and Warsawiii. This is because, firstly, in the UK Ukrainians are mostly concentrate in the capital, London. For comparative reason I have chosen the Polish capital, Warsaw, where Ukrainians are also found in significant numbers. Secondly, and more importantly, however, is that diaspora organisations are typically concentrated in the capital of the country because of their interest to communicate to the power structures. Therefore, the centre of diaspora and Euromaidan activities, which are the focus of this study, were mostly held in the capitals. Some interviews were also conducted in other cities of the UK and Poland. Each interview lasted between 45 and 90 minutes and included open-ended questions. The material was anonymised, coded, and analysed using NVivo software. Representatives of diverse Ukrainian diaspora organisations, community leaders, businesspeople, activists, and volunteers were interviewed, who remain anonymous to protect their privacy. In addition, I conducted some interviews with government officials, notably embassy staff as well as experts in Ukraine.

III. Research findings

1. Ukrainian diaspora mobilisation: resonance of the Euromaidan movement

The Euromaidan and the war in Eastern Ukraine have mobilised activists, volunteers, associations, various Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and foundations, students in both countries and the Ukrainian minority population in Poland.

All actors quickly responded to the events in Ukraine. Almost every Ukrainian NGO in London and Warsaw and many active citizens in the UK and Poland are putting efforts together to help and support Ukraine. Parallel diasporic spontaneous mobilisations of the Ukrainian diasporic community occurred in both countries resulting in foundation of ‘London Euromaidan’ and ‘Warsaw Euromaidan’. One of the founders of “London Euromaidan” explained:

London Euromaidan has started on the very same day when Euromaidan in Ukraine began. It was in November 2013 and people spontaneously came out in front of the Parliament to show support to Euromaidan in Ukraine and urge British government to put pressure on the Yanukovitch government. It was our first demonstration and after that people assembled regularly. A core group of volunteers has come together and established London Euromaidan. (int. 4)

Another interviewee described mobilisation in Warsaw and foundation of “Warsaw Euromaidan”: “When Euromaidan started, everybody got mobilised like in all countries. Many different people, including students joined us and all together we started organising protests near the Russian Embassy, marches in Warsaw. Then “Warsaw Euromaidan” was founded” (int. 37).

Citizens were activated in both countries, responded immediately to the events in Ukraine and provided a diverse support to Euromaidan. Within a few days people of all ages, and with different social backgrounds and careers, all with the same enthusiasm, became volunteers. As expressed by one of the interviewees:

When “Warsaw Euromaidan” was founded, S. and myself have been active participants. We have been doing everything we could. Sometimes we helped with microphones, sometimes with posters. Later we created different sectors. S. was a head of “Art sector”. I was responsible for the design, printing, and delivery of posters. We have been doing all these at weekends, after our studies. (int.37)

Another interviewee from Warsaw, who worked at that time at the Ukrainian school, said:

I was among ‘Warsaw Euromaidan’ people. I borrowed loudspeakers for Maidan. If there was a need to cook something for wounded guys or to help them to get to the doctors for consultations I helped. We also helped guys after their surgeries, we helped with translations or in case they wanted to talk we were there with them. They needed psychological support. (int. 31)

Diasporic organisations throughout the countries actively supported the Euromaidan protests and contributed to the organisation of humanitarian aid to Ukraine. For example, the Ukrainian Youth Association in Great Britain joined the demonstrations, which were organised in London, Manchester in Leeds: “We basically joined everything being organised and also, we wrote to MPs, trying to get support for the Ukrainian cause.” (int. 10)

The representative of the old diaspora in London stressed that the Ukrainian diaspora “always supported Ukraine in difficult times. When catastrophe in Chornobyl happened, when there were floods, the diaspora organised fundraising. Also, the diaspora helped in all revolutions - Orange revolution, in the last Revolution of Dignity” (int. 6).

Ukrainian churches in both countries have responded to Ukraine’s crisis and offered their support. A representative of the church from London revealed:

Ukrainians are very active here. They participate in protests during the Euromaidan. People gathered near the statue of St. Volodymyr, near Parliament. We organised a prayer here in the Church, we collected clothes and money. The other day we consecrated three cars which later went to Ukraine. (int. 21)

A representative of the church in Warsaw said:

We organise help to Ukraine in different forms. Firstly, it is fundraising and second is a collection of the money for some special purpose. For example, purchase of the ambulance for Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) or help to the children who lost their parents in ATO. A lot of money was collected when 40 wounded Ukrainians were here, in Warsaw in hospitals. Some soldiers were discharged from the hospitals and needed some control checks. The state funded everything in the hospitals, but not outside the hospital. Our church collected a lot of money for this purpose. (int. 35)

Thus, Euromaidan triggered the diasporic resonance and mobilised large numbers of Ukrainians in both countries. The Ukrainian diaspora experienced a “people power” revolution, mobilisation of individual protesters and activists as well as diasporic and newly founded organisations. From my interviews and observations, and by referring to the categorisation offered by Lyons (2006), Young and Park (2009) and Koinova (2011) it can be concluded that the Ukrainian diaspora mobilised not in a radical way but acted moderately by staging peaceful protests and campaigns, lobbying, supporting democracy, diffusing democratic ideas and practices.

2. The formation of a new Ukrainian “diasporic community”

Tragic events at Euromaidan, the annexation of Crimea, and the war in Eastern Ukraine have inspired newcomers in both countries to become involved and to make powerful contributions to their homeland. In turn, these led to the formation of a new Ukrainian “diasporic community”. Some have become members or supporters of well-established or new diaspora organisations. Interestingly, my research showed that in some instances, there was a clear overlap between different groups when, for example, a newly arrived highly skilled labour migrant nevertheless became member of an old diaspora organisation, the “Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain” and then one of the leaders of the newly founded “London Euromaidan”.

The formation of a new diasporic community in the UK was described by one of the community organisers in London:

The Ukrainian migrant network increased, the number of members has almost doubled, so it is difficult not to notice. Because of the events in Ukraine, there are existing organisations and new groups started forming and joining the network, because we try to keep everyone in touch as much as possible, inform what others are doing and what others are planning, so people can participate as well. The only difficulties I have that this increase of community effort and community organising was caused by bad things happening in Ukraine. I wish it were different. I wish something positive happened in Ukraine and then these entire group sprout out, grown out from positive developments. (int. 3)

The dynamics of the new diasporic community was positively described as:

All these organisations, London Euromaidan, Ukrainian events in London, they all started as an embryo, had no shape or form, no strategy, no very clear structure. But with time I was so proud to see how all these groups in their own way were shaping up and developing into proper structures, taking strategies, having meetings, discussing needs. (int. 3)

Remarkably, the Euromaidan mobilised also significant numbers of previously inactive individuals around an important issue. One interviewee from Warsaw shared her experience: “Maidan and the war mobilised people here [in Poland]. I could say about myself that before all these negative events I did not do much. Now many people come and are ready to help” (int. 33). This is typical for one of the diaspora members categories suggested by Shain and Barth (2003, p. 452), the silent members that are a larger pool of people who are generally uninvolved in diasporic affairs but who may mobilise at times of crises.

From the interviews it became clear that people of different background, skills, age, duration of stay and migratory status got united due to the Euromaidan: “Then Maidan started and all people who wanted to help have united. They wanted to help from here [Poland] as much as they could” (int. 40); “The Maidan was definitely uniting people. We have seen people coming out from various parts. Many businessmen arrived to support Maidan in London. People becoming more active, and it shows that status-quo has been changed with the existing organisations” (int. 15).

Crucially, all these segments complement one another, as expressed by the interviewee:

One of the things I was very proud of when Maidan started in Ukraine was that each and every different Ukrainian community group was doing its bit, the best they can at the place where they were. “Ukrainian Medical Association in the UK” took over medical issues, issues with hospitals, wounded people. “London Euromaidan” had people who collect, fundraise, and get supplies for the frontline, for volunteering battalions and from the same group at the same time people who have skills in networks, would go to the media and talk in front of camera, with microphone, making people aware. Others with skills and networks would go to Parliament and raise issues or at least make people aware, challenge the government, do this kind of work. Somebody is linking people with the media. (int. 3)

In line with Dunin-Wąsowicz and Fomina (2020), my findings showed that the Euromaidan mobilised various groups within the broadly defined Ukrainian diasporic community, including many people who had never previously been civically engaged.

3. The Ukrainian diaspora claims to be recognised as an important actor

Diasporas are increasingly acknowledged as important actors in development in relation to their countries of origin. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and some Ukrainian officials acknowledged that Ukrainian migrant workers are the biggest investors in Ukraine’s economy. Ukraine is the largest recipient of remittances in Europe and Central Asia, receiving a record high of nearly $16 billion in 2019 (World Bank, 2020).

As the war in Ukraine is far from over the important contribution the diaspora makes apart from remittances is the provision of humanitarian assistance: “We continue to fundraise; the war is not over. The ceasefire in not really real. We continue to supply a lot of medicine, uniforms and other things” (int. 4).

A co-founder of the British-Ukrainian charity organisation explained how they contribute to the homeland:

We developed three main areas of help [to Ukraine]. Firstly, it is help with prosthetics, help with providing medical treatment. Secondly, it is help to families, internally displaced people. The third area is children of heroes, that were breadwinners during the war. (int. 9)

From the interviews with the representatives of the Ukrainian diaspora and by referring to the categorization suggested by Shain and Barth (2003, p. 452), it can be argued that the Ukrainian diaspora has all prerequisites - motive, opportunity and means - to be an active and successful diaspora. In line with Al-Ali et al. (2001), it also has desires and capacities to engage in transnational activities, it developed social competences and political literacy, knowing how to lobby, campaign, speak in public and write leaflets. However, my findings go beyond Al-Ali et al. study (2001) who suggest that capacity among other things, requires security of status. From my interviews it became evident that even irregular migrants can be active diaspora members. They have supported Ukraine’s cause with great effort, be it financial and medical aid for the Ukrainian army and volunteers fighting in Donbas, be it supporting households back home through remittances, be it supporting social media or lobbying democracy in Ukraine through various forms of political and social activism.

Essentially, the old and the new diaspora in the UK and Poland claim to be recognised as an important stakeholder for the development of Ukraine. The leaders of the “Maidans” in London and Warsaw referred to the political influence they can leverage through lobbying and awareness-raising campaigns in the country of residence. As expressed by the representative of “London Euromaidan”: “We became very active in political terms. Another area of Euromaidan work is political lobbying. Our activists attend different sessions in Parliament, speak to members of Parliament’ (new diaspora representative)” (int. 4).

A representative of the “Warsaw Euromaidan” described their activities as followed:

One of the most important is political activity, which includes preparation of official letters, petitions to Ukrainian and international politicians who can influence the situation in Ukraine. We are also doing preparation of political events, marshes, and pickets of embassies. Besides, we do lobby for Ukrainian interests. (int. 30)

A new diaspora representative believed that apart from financial help the Ukrainian diaspora can contribute by way of constructive criticism: “We are also not afraid to criticise the Ukrainian government where it is necessary” (int. 4). Almost all my interviewees agreed that the diaspora has an ability to counter misinformation on Ukraine (“The other thing diaspora might be able to help with is trying to propagate or to stem the flow of misinformation about Ukraine”; int. 10).

The diaspora is also a source of the soft power of a country; spontaneously without being appointed these actors are voluntary ambassadors and cultural diplomats abroad. One of the leaders of Ukrainian diasporic community in Warsaw stated: “We participate in conferences, round tables, represent our state. We also go to Polish mass-media, organise different events and attract attention to Ukraine. Often, we are invited to TV to comment on some event” (int. 30).

Another important contribution diaspora makes is the promotion of Ukraine abroad. For example, as the representative of the cultural institution in London said:

We are working de-facto as Ukraine’s cultural institute and serving a platform for debate about Ukraine, engaging key influencers in the UK, bringing Ukrainian artists and thinkers over to the UK, working with leading UK institutions, such as British Library, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, running Ukrainian language school. (int. 19)

The representative of the Embassy of Ukraine to the United Kingdom provided illustrative example of the Ukrainian diaspora’s in the UK positive impact on the ground:

A Ukrainian woman came to us and said that in her child’s school geography textbook Crimea was a part of Russia. The publisher was “Oxford University Press”. Due to the activists who wrote numerous complaints, and a diplomatic request Oxford University Press fixed the error and reprinted this book where Crimea is a part of Ukraine. (int. 16)

IV. Final remarks

This paper explored the Ukrainian diaspora mobilisation in the UK and Poland triggered by the Euromaidan and the Russian aggression against Ukraine from the end of 2013. These events in Ukraine have mobilised diasporic communities and triggered a powerful wave of diasporic activities in the UK and Poland. My findings challenge the neat distinction between diasporas and immigrant communities and the narrow conceptualisation of diaspora based on their historic roots. I suggest defining diaspora as peoples’ concrete engagement in diasporic activities and identities, no matter whether their ancestors have migrated or whether they have migrated only recently. Consistent with Koinova’s (2015) definition of “diaspora mobilisation”, the Ukrainian diaspora in the UK and Poland behaved in a way to make homeland-oriented claims bring about a political objective and contribute to a cause. Drawing from the literatures on social movement, the contribution shows that transnational diasporic mobilisations in the UK and Poland may be seen as “extensions” of the Euromaidan social movement and are in line with Sökefeld’s suggestion that concepts developed in social movement theory can be applied to the study of certain activities diaspora communities.

My empirical data confirms that the Ukrainian diaspora and the communities of Ukrainian migrants in the UK and Poland have the resources, power, and a willingness to contribute to the homeland. The study showed that the Ukrainian community has united and grown stronger due to the events in Ukraine. Also, the Ukrainian diaspora transformed from more inward looking to more outward looking communities who as a result are now more engaging with Ukrainian affairs. From the interviews and consistent with Al-Ali et al. (2001) and Shain and Barth (2003) it can be argued that the Ukrainian diaspora has the desire, motive, opportunity and means to engage in transnational activities, at least for the time being, which makes it an active and successful diaspora. Moreover, diasporic communities in both countries claim to be recognised as an important stakeholder.

The findings of the study raise important questions for scholarship on diaspora mobilisations. There are at least three important areas which would benefit from further research. The first question for future research is whether the diaspora’s motivation to engage in Ukrainian matters will and can be kept alive. A second area, which would benefit from future research is to explore what happens between waves of activism, in concrete places and communities in order to explain diaspora mobilisation abroad. And finally, it is useful to ask which determinants drive people fading out of diaspora activities.