I. Introduction

The border, which is part of a current reality that divides territories according to the criterion of limits, has had different approaches and studies. In some cases, borders have coincided with geographical features, but these, as they are known nowadays, have been created under certain parameters. This has sometimes generated conflicts of interest that have affected the territory. However, being the border a historical evolution, what role has history played in resolving conflicts? And can the geographical factor also be a determining factor in their resolution? Such tension underscores the importance of studying the border from not only a historical perspective but also from geographical and territorial perspectives. Taking all those stances helps to analyse the process of the border’s contemporary demarcation, which, despite its acknowledged temporal stability, was not always simple. The main objective of this article is thus to focus on the conflicts that delayed a simple demarcation of the border and to remark whether they shared any kind of typology.

The article is the result, in part, of growing interest in how European borders were constituted in the nineteenth century and the role played by the different international joint boundary commissions in the consolidation of borders (Biggs, 1999; Di Fiore, 2017; Donaldson, 2008; García-Álvarez & Puente-Lozano, 2015, 2017; Guy, 2008; Sahlins, 1989). In turn, at the end of the twentieth century, historiographical, geographical, and anthropological works on Iberian borders began to emerge (Capdevila, 2009; Dias, 2009; Godinho, 2011; Kavanagh, 2011; Lois González & Carballo Lomba, 2015; Medina, 2006).

The article starts with the premise that the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were decisive for the formation of Spain’s borders, both in Europe and in its colonies, due to several bilateral agreements - such as the Treaty of Utrecht (1713-1715) after the War of the Spanish Succession - that preceded the formation of the current Spanish state. That process was long, slow, and, at times, complicated. After all, from the moment that the borders between states were formed, some of them became known for border tensions. In other cases, tensions arose at the very moment when the specific border was to be delimited or else developed later once the border had in fact been delimited. In any case, each of those border conflicts has been governed by similar parameters and characteristics in most cases, and their differences are therefore mostly found in how they have been resolved. Even so, not all border conflicts are governed by the same territorial premise, for historical, geographical, and social issues, in addition to territorial ones, have significantly influenced the history of those conflicts.

Added to that, despite extensive studies and literature on what borders and cross-border conflicts are, the use of certain terms is confusing, and the same questions are often repeated - for instance, what is the definition of border? Is it the same as the definition of boundary? Even once those concepts have been defined, the questions of why border conflicts appear, what their causes are and how can they be resolved arise. Sometimes, in the sciences related to territories and borders, as in geography, addressing the concept of borders remains complex from both a contemporary and historical perspective due to its ambivalence, that is, the practical difficulty of reconciling its physical and political definitions (Neuman, 2014). For the case study, this complexity can be solved since in Portuguese and Spanish there is only one single word referring to the border (fronteira/frontera, respectively) and when the boundary is described it is done explicitly.

This article’s contribution is not simply a review of the current conceptualisation of the (historical) border and a presentation of a typology of conflicts in the case study. Beyond that, it advocates an account - the same sort of account that it offers - of historical factors with geographical factors as well as territorial factors with factors of sovereignty. In that way, a methodology is created that can be used to analyse cross-border conflicts, both European and on other continents, where the outcomes have not necessarily been violent or warlike but rather constituted a process of delimitation or agreement by the governments to end the discrepancies that had generated over time, although the delimitation in itself does not mean that the conflicts will disappear or that they have developed in the same way along the entire Spanish-Portuguese border.

Based on that premise, this article focuses on the case of the southern border between Portugal and Spain, considered the oldest and most stable in border in Europe (Kavanagh & Jiménez, 2018). In addition to explaining what kind of conflicts factored into the modern delimitation, the article also discusses how they were solved, for although a certain stability in a territory can be sensed, that does not mean that disputes were absent in the process of delimitation. To that end, the article has been divided into three sections, followed by final conclusions. The first section sets out the theoretical background and interrelates four basic blocks of concepts that can help to analyse any European cross-border conflict in the nineteenth century: boundary/border/frontier, border studies/historical studies, sovereignty/territoriality, and territorial disputes/boundary disputes/territorial conflicts. The second section provides a brief overview of the border’s historical context and the major conflicts between Portugal and Spain there. Last, the third section presents the typology of the conflicts in the case study and the resolution reached by the governments and the Boundary Commission. The article concludes by reflecting on whether those conflicts should be called border conflicts or whether, on the contrary, they are mere disagreements between states over wanting to delimit a linear border under any pretext and that, if the ideal had not been achieved, then no conflict would have arisen.

This article has depended on archival sources containing the opinions of both governments and the correspondence of the Boundary Commission for the final delimitation of the border, as well as current theoretical references addressing the emergence of nation states and the determination of borders in Europe. With those sources, a review of both historical and current documents was conducted to gain insight into the history of the delimimation/demarcation of the border and form an approximate interpretation of the objectives pursued by nations when delimiting their territories. The archival documents concern the work of the Boundary Commission that created the Boundary Treaties and, at the same time, work generally related to the border and the territories focused on herein. That documentation has been extracted primarily from: i) the Arquivo Histórico-Diplomático do Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros (Historic Diplomatic Archives of the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, AHD-MNE), Lisbon, Portugal; ii) the Archivo General Militar de Segovia (General Military Archive of Segovia, AGMS), Segovia, Spain; and iii) the Archivo Cartográfico y Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército (Cartographic Geographical Studies Archive of the Spanish Army Geographic Centre, ACEG-CGE); and iv) the Archivo Central del Ministério de Asuntos Exteriores y Cooperación (Central Archives of the Spanish Ministry of Cooperation and Foreign Affairs, AMAEC), in Madrid, Spain.

II. Theoretical background

This section draws a common, essential line between four blocks of basic concepts that help to analyse and clarify most border conflicts that developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in Europe. Even though theory of borders has been widely studied and cited and despite the extensive bibliography on the topic, it is important to review them here in order to more fully illuminate the case study as a synthesis of a reflection on the past made in the present.

First, although the terms border, boundary and frontier are often used interchangeably, the concepts differ slightly. The concept of boundary is the most precise, that is, the coordinates and milestones through which the line separating two territories passes. After the Thirty Years’ War (1648), the Westphalian system - or Westphalian sovereignty or state sovereignty -, appeared in Europe: borders mark the territory and sovereignty of states. Nation-states begin to emerge (Foucher, 1991; Hobsbawn, 1991). Since borders mark sovereignty and thus the power of the monarch over his territory, it appears the concern to have them well demarcated (Mingui, 2018). In the case of Portugal and Spain, the demarcation of the boundary was performed by a Boundary Commission that made an in situ study of the territory, after which an agreement was reached between the two national governments to determine where the boundary between the two countries would pass. The result was the Treaty on Boundaries (1864) and the Convention of Limits (1926). The boundary is therefore delineated on a map and demarcated in the territory. In short, as the case shows, a boundary simply separates one sovereign territory from another (Ranjan, 2018). By contrast, a border is the area, regardless of size, located in the external or peripheral part of a state and whose limit is a national border. Between Portugal and Spain, that area has been known as “the Stripe”, a Raia in Portuguese, la Raya in Spanish - where a border identity has developed and where so called raianos/rayanos, the inhabitants of the area, live. In that specific case, the border was the place where coexistence, once achieved, triggered social, economic, and commercial hybridisation. At the beginning of the twentieth century, after the construction of modern borders was consolidated, the first studies on how they were formed emerged. Some authors advocated the theory that borders were artificial constructions (Kristof, 1959; Prescott, 1965) and others classified them according to specific aspects, as in the case of Hartshorne (1936, 1938), who related them to the cultural landscape at the time they were established. This same author developed four premises for the study of border conflicts: all borders are artificial because of their human construction; borders can always be disputed; the problems of a border are translated into human terms; and the consequences of these conflicts affect the border population the most. Third and last, the frontier is a political limit that divides two states but does not need to be under the control of any state (Binder, 2017).

In view of those definitions, the question arises as to which discipline studies those three concepts. A priori, the answer might be border studies, as a discipline that has developed exponentially in recent decades and, in the process, increased the theory of borders and its different concepts with a contemporary vision and begun to appear in geography, history, political science, sociology, anthropology, often in conjunction with different perspectives and approaches, including the geopolitical. However, the historical component that has appeared in border studies has been brief and the few historical studies that have been devoted to the topic of borders despite their importance have been highly fragmentary (Di Fiore, 2017). Consequently, border studies not only focus on borders and other studies as historical, geographical and cartographical have emerged for different ways of analysing the past. Some of the earliest research to take a historical perspective on borders was by Willem van Schendel and Michiel Baud (1997) with an essay comparing the history of borderlands in various geographical scenarios. In 2013, Stuart Elden was one of the first authors to analyse the historical concept of the border by developing how the notions of border and territory emerged (Elden, 2013). In that light, the relationship between border studies and historical studies continues to develop today because of its importance.

However, border studies and territory studies cannot be understood without addressing sovereignty, nor sovereignty without territoriality. Territory is one of the principal terms in geography and is widely used in various disciplines. In this article it is worth highlighting the common definition adopted by geopolitics which defines territory as a space under a state’s sovereignty (Taylor, 2000). In parallel, to understand modern territoriality and the concept of sovereignty associated with it, the techniques of delimitation, the representation of borders and the political organisation of space that emerged in the nineteenth century have to be taken into account. Territory is viewed as a symbol of power by which states can access natural resources and develop national strategies. According to Agnew (2008), if a state is clearly delimited, then it is a key feature for international relations and the further enhancement of its power. However, Agnew (1994) has also advocated the now well-known so called “territorial trap” theory of dominant hegemony. The concept of territoriality, traditionally been attributed to the rise of modern nation states, has also changed, or in Paasi’s words, the role and meaning of a state’s territoriality and sovereignty have changed (Paasi, 2005). This change refers to the fact that it represents the reification of how the world is like and how it should be organised. The emergence of certain institutions (political, educational, communication, etc.) becomes a territorial unit linked to a spatial structure. The idea of territory is tied to political and social ideology. Other authors have studied the changing territorial dimensions of states and their repercussions on sovereignty, as mentioned throughout this article (Ferguson & Mansbach, 1989; Ruggie, 1993). In the context of borders and territories, the concept of sovereignty assumes an important role for, via sovereignty, political authority can be linked with territory (Thomson, 1995). Thus, the relationship between borders and sovereignty is direct, for borders impose limits on political, social, and cultural sovereignty (Brunet-Jailly, 2011; Paasi, 2009). That concept of sovereign statehood was developed by Max Weber (2013) in Economy and Society which elaborates the theory that a chief aspect of sovereignty is the ability of a political organisation, here, a state, to use force within a territorially delimited area. If states wield control only in the territory to which their political control is attached, then borders play the role of delineating sovereignty.

In contrast to the sovereignty of absolute monarchies, which were based on the idea of the sovereign’s power over the subjects, liberal states focused on a sovereignty that was national and territorial in character. This meant that jurisdiction had to be exclusive to their territory, which was well defined by borders (García-Álvarez, 2019). The Portuguese/French/Spanish boundary treaties of the mid nineteenth century reflect this type of sovereignty (Flint & Taylor, 2018; Popescu, 2012; Teschke, 2006). In contemporary political geography discourses when the emphasis is placed on boundary-making it is done under a categorisation, and when reference is made to the practice of boundary-making it is done retrospectively. The development of boundaries is studied as distinctive rather than examining the practice itself, or no distinction is made between demarcation and delimitation practices. An example of this is the case of the work of Flint and Taylor (2018) who argue for boundaries as divisions of sovereign states and the border as an essential element of the modern world economy. Thus, the process of boundary creation is different in various sections of the world economy.

Last, regarding the differences between territorial disputes, boundary disputes and territorial conflicts, territorial disputes are disagreements over pieces of territory claimed by two or more countries (Guo, 2015). Following Huth’s definition (1998), territorial disputes refer to instances when at least one government does not accept the definition of where the boundary line of its border with another country is currently established, whereas the other government relies on a signed treaty or document to confirm that the boundary line is the legal border between the countries. By contrast, boundary disputes refer to conflicts related to drawing border lines and where boundaries pass, whereas territorial conflicts refer to conflicts over larger tracts of land or water. Despite those theoretical distinctions, in practice the terms hardly differ, for most territorial disputes are related to land or water. What is clear, in any case, is that boundary disputes and territorial disputes frequently arise because political boundaries are inappropriately or imprecisely defined, except ones defined either by latitudes and longitudes or by other quantitatively identified coordinates, hence the importance for nation states to define their boundary limits well.

As a conclusion to this point and in order to proceed to present the case study from a critical perspective, the contemporary geographer Foucher (1991) highlights the “false dilemmas” about borders. The author distinguished five types of borders that can be summarised in his first classification: are borders natural or artificial? Taking into account the above, and focusing on the fact that this article deals with the problem of the final delimitation of the border between Spain and Portugal, it could be affirmed that borders are artificial because if they were natural, could there be a conflict? And following the line of the aforementioned authors, every border is a construction. Likewise, there is a clear distinction between what is the zona-border (zonal border) and the line (linear limit) because the latter is the invention that appears on a map, or according to Foucher (1991) the border line is an elegant invention of cartography. The same author argued that borders serve as a political marker and are governed by legal texts (Foucher, 2007). Borders have a triple register: i) real, marking the exercise of sovereignty; ii) symbolic, belonging to a political community inscribed in a territory; and iii) imaginary, how those belonging to one territory relate to those of another (Foucher, 1991). Finally, this article has also focused on Houtum’s (2005) critique that, although all borders are artificial because they are made by humans, the nature of the border itself could be studied not only in how they are created but why.

III. Historical context of border disputes between Portugal and Spain

As mentioned in the previous section, understanding the process of border conflicts between Portugal and Spain requires revisiting the eighteenth century when the enlightened monarchies of both nations promoted different treaties to establish a precise, linear, continuous boundary between their territories. However, it should be borne in mind that the boundaries that had been developing since the twelfth century also played a key role in understanding the conflicts of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Spanish-Portuguese border, although the concepts of border and its recognition as such have already been clarified, dates its origins to the Middle Ages. The first treaties that contemplated the border between both kingdoms were three: the Treaty of Zamora (1143), the Treaty of Badajoz (1267) and the Treaty of Alcañices (1297). The first of these treaties (even though it is not known with certainty that it was signed and how it came about) granted Portugal the title of independent state and the birth of the Kingdom of Portugal (Gaspar, 1985; Saraiva, 1989). While the first treaty preceded what would later between the two kingdoms. The border between Castile and Portugal was fixed at the Guadiana River. The lands located to the west of the river would belong to Portugal and those located to the east to Castile. This panorama changed with the Treaty of Alcañices (1297) when certain territories east of the river would become part of Portugal. As a starting point, the Treaty of Alcañices meant that the border was partly defined (Cosme, 1992). Because of this treaty, this border is also known as one of the oldest in Europe, mainly because the agreement lasted over time (Ladero Quesada, 1998), although some authors claim that this border is not the oldest in Europe due to the different conflicts that have taken place (Braga, 2001). However, from this moment on, it is considered that the territorial disputes between Spain and Portugal over the municipalities of Taliga and Olivenza began, a conflict that will be discussed below.

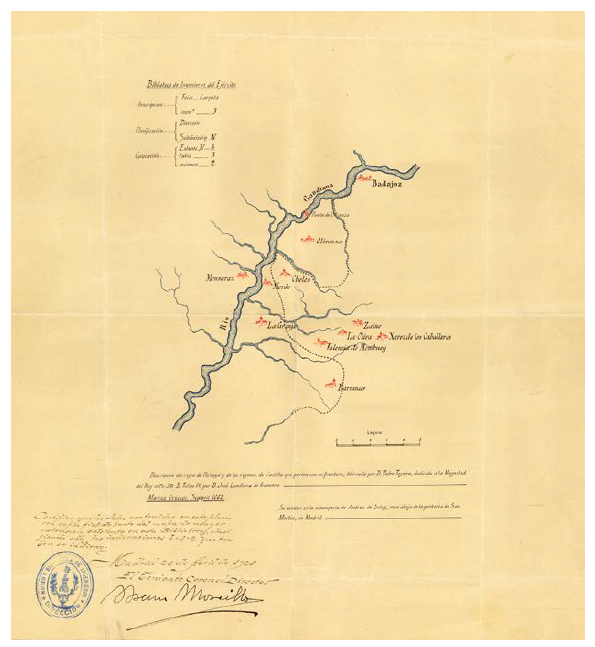

The border created with the Treaty of Alcañices gradually became, first, an area of expansion and, later, the line demarcating Castile and Portugal (fig. 1; Ladero Quesada, 1997). But how did a theoretical border - constituted by a treaty, and undefined, because it only listed villages, become a reality? Mainly because, after the signing of the Treaty of Alcañices, what exactly the agreement determined was specified and whether and how changes in the way the territory was used influenced the delineation of the border was taken into account (Herzog, 2015).

Fig. 1 Limit between Castile and Portugal in Olivenza in 1662. Source: ACEG-CGE (1926), Box 25, number 6

From the eighteenth century onwards, in the Contemporary Age, the treaties that were signed bilaterally during the ensuing years were the result of sovereignty that can be summarised as wanting to have territory defined well and limited to allow each nation to know how far its dominions reached. The outcomes of the new conceptualisation of territoriality were translated between Portugal and Spain in two treaties: the 1864 Treaty on Boundaries, signed on 29 September in Lisbon, and the 1926 Convention of Limits, signed on 29 June, also in Lisbon (D’Oliveira & Soares, 2001-2009). Whereas the former established the boundary from the mouth of the river Minho to the confluence of the river Caya in Guadiana, the latter established the boundary from the confluence of the rivers Cuncos and Guadiana to the mouth of the Guadiana in the Atlantic Ocean. Consequently, a small area between the rivers Caya and Cuncos that was not delimited remains the source of the still-unresolved Olivenza conflict (Sampayo, 2001). With the signing of those treaties, the states achieved their objective of strengthening control over the border territories, which, despite being regarded as marginalised, have constituted a key place for power and, more importantly for this article, a movement to end territorial conflicts that have existed in the border area as a place for smuggling and malefactors.

The Boundary Commission placed in charge of preparing and executing the treaties played a critical role via the demarcation acts that they drafted. They were primarily composed of military personnel with extensive geographic and cartographic knowledge who had worked in the field and had records showing precisely where the border passed based on territorial mediation techniques involving geodesic and topographic procedures (García-Álvarez, 2019). The Boundary Commission, when conducting field work and delimiting the border, encountered several conflicts scattered along it. In the case herein, perhaps the one that seemed to be the most conflictive was Olivenza, for its sovereignty involved a dispute between Portugal and Spain that had completely paralysed the work of the Boundary Commission for decades (Archivo Central del Ministério de Asuntos Exteriores y Cooperación, 1926). However, of the processes involved in delimiting the border, the most difficult to resolve were the contiendas (“disputes”) that, despite initially seeming trivial, proved to be pivotal in demarcating the border, for it was a question of recognising that some borders were subject to litigation (Santos-Sánchez, 2022). Those areas, which over time have had different temporary arrangements between the town councils and their neighbours, were generally subordinated to the question of ownership or private possession of the boundary line. Rights were based on imaginary and uncertain titles, if not arbitrary appropriation (Ramos Orcajo, 1891).

Since 1864, when the Treaty on Boundaries with Portugal was signed, delimiting the border in the part between the mouth of the Minho and the confluence of the Caya and Guadiana, the intention was to continue the border up to the mouth of the Guadiana. The idea was to take, as a baseline, the established boundary following the course of the Guadiana, including the space between the Cuncos to the north and the river Chanza to the south. However, for decades thereafter, no agreement was ever reached to delimit what was left of the border.

The southern area between Portugal and Spain saw three disputes or contiendas: i) the Contienda de Villanueva del Fresno; ii) the Contienda de Valencia de Monbuey; and iii) La Contienda, also known as the Contienda de Moura, the Contienda de Aroche and the Dehesa de la Contienda. To those disputes could be added the Contienda de Galiana, despite its lack of importance until far later than the others and its lack of major confrontations. On the contrary, there were no real deeds of ownership or sovereignty, and the inhabitants on both sides of the border used the areas simultaneously or alternately. Most of those disputed areas were cultivated or used for grazing, and although some of those disputes were resolved by dividing the territory into equal parts, including the Contienda de Mombuey, such a solution could not be extrapolated to others. La Contienda was the most complex to manage and the most difficult to delimit. At the same time, it was the largest of the three mentioned disputes, which makes its division even more complex (Herzog, 2015).

Olivenza does not fall within the framework of the contiendas because, although they had no title of ownership or sovereignty and were enjoyed simultaneously or alternately by both countries, Olivenza had clear sovereignty. However, the import of the delimitation was so controversial that the Boundary Commission’s work was postponed for years and, in fact, never completed. Portugal felt that it was the victim of an abuse of force, which was the primary reason why the delimitation of the 1864 Treaty had to stop upon reaching Olivenza’s perimeter and the most powerful reason for the delay in continuing the border’s delimitation (Arquivo Histórico-Diplomático do Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros [AHD-MNE], 1927).

The historical context of Olivenza dates to 12 September 1297, when its municipal district ceased to belong to the Castilian-Leonese monarchy with the signing of the Treaty of Alcañices between Ferdinand IV of Castile and Dinis I of Portugal. The purpose of the treaty was to end the wars and other conflicts between the two territories. In exchange for ceding Olivenza to Portugal, Ferdinand IV obtained possession of the towns of Aroche and Aracena. However, except for Olivenza, the entire east area of the Guadiana came to form part of Castile. With the wars of independence from Portugal that began in 1640, after nearly sixty years of Iberian unity, fighting became frequent in the vicinity of Olivenza. In 1657, it was taken by the Spanish but returned to Portugal in 1668 under the Treaty of Lisbon.

In 1801, as part of the so-called War of the Oranges, Olivenza was once again occupied by the Spanish (Pereira, 1960; Olivença, 1957). Subsequently, a peace treaty was signed in Badajoz on 6 June 1801 that put an end to hostilities between the two countries. Article III of the treaty stipulated that:

(España conservará Olivenza) en calidad de conquista, para unirla perpetuamente a sus dominios y vasallos; así como sus territorios y pueblos hasta el Guadiana; de suerte que este río sea el límite de los respectivos reinos en aquella parte que únicamente toca al sobredicho territorio de Olivenza1.

By virtue of that clause, Spain took possession of the territory of Olivenza and has never since abandoned its possession. Moreover, it has in no way been obliged to cede the territory to Portugal. In 1808, the Prince Regent D. John VI denounced the treaty of 1801 and since then Portugal has been putting forward different arguments for Olivenza to be returned to them. The subsequent Treaty of Paris (30 May 1814) between Portugal and France was considered to be annulling; however, this only applies to France and not to Spain. Another argument why Portugal does not recognise the sovereignty of Olivenza to Spain is by article 105 of the Final Act of the Congress of Vienna (9 June,1815):

As Potências europeias, reconhecendo a justiça das reclamações formuladas por Sua Alteza Real o Príncipe Regente de Portugal e do Brasil, sobre a vila de Olivença e os outros territórios cedidos à Espanha pelo Tratado de Badajoz de 1801, e considerando a restituição destes objectos como uma das medidas adequadas a assegurar entre os dois Reinos da Península aquela boa harmonia, completa e estável, cuja conservação em todas as partes da Europa tem sido o fim constante das suas negociações, obrigam-se formalmente a empregar por vias conciliatórias os seus mais eficazes esforços a fim que se efectua a retrocessão dos ditos territórios em favor de Portugal. E as Potências reconhecem, tanto quanto depende de cada uma delas, que tal retrocessão deve ter lugar rapidamente. (Final Act of the Congress of Vienna, 1815, n.p.)2

Nevertheless, article 105 did not establish an obligation of result, but of behavior (Fernández Liesa, 2004). On 7 May 1817, Spain finally signs the Treaty of 1815 (Luna, 1994), but the text is not mandatory on demanding Spain to return Olivenza to Portugal. As the promise of Olivenza’s return was delayed, it was never carried out, and the Congress would not have sufficient legal force at the international level to enforce the order. From the Spanish point of view, the Treaty of Badajoz is the one that remains valid. From the Portuguese point of view, it is considered null and void, so the discrepancy continues and with it the “Questão de Olivença” (Olivenza’s question) (Svobodová, 2016). However, the seizure of Olivenza caused Portugal to feel victimised by an abuse of force, which has sometimes clouded the traditional cordiality of relations between the countries. From another angle, the turn of events suggested that the dividing line between the countries should be formed by a natural obstacle, in this case, the Guadiana.

IV. Typology and final resolution: the work of the boundary commission

Following the previous brief historical review explaining why and how border conflicts between Portugal and Spain arose, it is worth highlighting the typology of conflicts that have appeared in the southern part of the border, even though they can readily be extrapolated to any other border. It should also be mentioned beforehand that, unlike the studies of border conflicts in the northern part of the Portuguese-Spanish border based on the linear constitution of limits, as has been extensively studied in recent years, such has not been the case for the border’s southern part. Moreover, the Olivenza`s conflict is sometimes excluded from that categorisation of conflict, even though it was an important highlight for understanding the final consolidation of the border between the two states. An example of this is Tamar Herzog’s book (2015) which only focuses on La Contienda because it does not consider Olivenza as a dispute.

According to the typology, most of the mentioned conflicts have taken place over disputed areas or the non-recognition of their sovereignty. Thus, along the border’s southern part, two types of conflicts primarily developed: the changing sovereignty of spaces (Olivenza) and undivided spaces (contiendas). For the first type of conflict, no treaty was created by a specific commission; for the second type, a treaty was created. However, as literature addressing the 1864 Treaty on Boundaries shows, the contribution of those treaties was not to establish a linear border per se but for two other reasons directly related to the cross-border disputes mentioned above: one, to guarantee territorial sovereignty, the importance of which was defined in the theoretical section, and two, to perpetuate national security with a well-defined administration (Cairo & Godinho, 2013; García-Álvarez, 2019). The latter is the chief reason why, after signing the Treaty of 1864, both the Spanish and Portuguese governments wanted to resume work to complete the delimitation of what remained of the border (Archivo Cartográfico y Estudios Geográficos del Centro Geográfico del Ejército [ACEG-CGE], 1921, 1926; AHD-MNE, n.d.).

For the resolution of the disputes and the subsequent signing of the 1926 Convention of Limits, the work of the Joint Boundary Commission was essential to verify and recognise the terrain of the borderline. Likewise, the nationality of the population of la Raya had to be resolved, especially in order to settle disputes, for the group was not defined as either Portuguese or Spanish. However, with the signing of the treaty, la Raya did become part of one; they were not considered to be citizens of the state per se, however, and a negative view was attributed to them, one connoting smuggling and violence (Herzog, 2015). That argument was used by the governments to intervene in la Raya and exercise their sovereignty in the territory, above all by claiming the need for peace between the rayanos of both Portugal and Spain. When those territories were divided, the aim was to ensure that the populations could easily access the resources necessary for their subsistence without harming the inhabitants (García-Álvarez & Puente-Lozano, 2017). The following showcases the solutions and the end of the disputes according to their typology.

1. The changing sovereignty of spaces: Olivenza

Some of the most enduring and sometimes dangerous territorial disputes often involve historical property claims by at least one interested party (Fang & Li, 2019). Such has been the case of Olivenza, where territorial claims have not emerged arbitrarily. One of the reasons why such disputes often arise is because of historical precedents, which provide more opportunity for the claim than a simple argument about resources or population (Abramson & Carter, 2016). Although historical ownership can be a territorial claim, the repercussions for the claimant country have to be considered, as does what kind of negotiations are needed between the leaders and the support or failure of the negotiation (Murphy, 1990).

In Olivenza’s case, ranked among conflicts of territorial claims and as shown in its historical context, the region has belonged to Spain since the Treaty of Badajoz in 1801.

Finalmente, entre as desembocaduras, no rio Guadiana, dos rios Caia e Cuncos, a fronteira é litigiosa, correspondendo à povoação de Olivença, em virtude do Tratado de Paz, entre Portugal e Espanha, de 1801, não ter sido ratificado pelo Governo Espanhol. (AHD-MNE, 1933, n.p.)3

The disagreements between Portugal and Spain brought the delimitation that began at the end of the century to a complete standstill in Olivenza. On several occasions, the Spanish government requested that the work be resumed. In 1869, the Portuguese Government showed interest in continuing the delimitation in a note dated January 7 written by the Portuguese Minister in Madrid, Conde de Alte, and which expressed “the convenience that the demarcation of the Spanish-Portuguese border takes effect until the confluence of the Caya River into the Guadiana (…) extends until the mouth of the last sea of these rivers” (ACEG-CGE, 1869, n.p.). From that moment on, the dialogue between the Spanish and Portuguese governments began. However, before the Spanish Government replied to the aforementioned note, there were two territorial issues that could still be of concern to Spain and on which it sought Portugal’s opinion. One, which had been successfully resolved, concerned the possession of Monte de la Magdalena (Couto Misto and the promiscuous villages). Another, which was expected to create tensions with Portugal over Olivenza. Finally, it was decided to reply to the note of April 6, 1869 to the Plenipotentiary Minister of Portugal with the Spanish Government’s acceptance of the Portuguese proposal. In turn, orders were given to the Spanish Commissioner, Pérez de Castro, to begin working with the Portuguese Commissioner and to reach agreement on the course to be followed for the demarcation of the border line from the confluence of the Caya river with the Guadiana to the mouth of the latter in the sea and to gather information on the ideas and aspirations of the Portuguese Government with regard to Olivenza (ACEG-CGE, 1869), “There is, however, when the plaza of Olivenza is referred, a question that more than place is politics and that consists of the aspiration of the Portuguese Government for the plaza, ceded to Spain by the Treaty of 1801 (…)” (ACEG-CGE, 1871, n.p.).

In 1890, La Contienda was resolved by the Convenio de Límites entre España y Portugal en la Dehesa de “La Contienda” (Convention of Limits between Portugal and Spain in the Dehesa de La Contienda) signed in Madrid on 27 March 1893, as discussed below. At that time, an attempt was made to take advantage of the Commission’s activity; however, the Portuguese government was once again negative, and fearing the repetition of the Olivenza problem, all action was brought to a halt.

(…) y el Sr. Hintze me notificó los deseos que animan a este gobierno en el sentido de que tal delimitación tenga efecto; si bien indicó no podría ser en tiempo y forma cosa tan breve ni tan ligera como parecía que apreciaba el Sr. Freuiller; pues no solo exigirá un trabajo semejante al que hubo que hacer para delimitar lo que ya se terminó, al aprobar el tratado de la Dehesa de la Contienda, sino que la circunstancia de hallarse la plaza de Olivenza enclavada en la parte que se ha de demarcar, hará necesaria la natural detención y estudio para la resolución del asunto (Archivo General Militar de Segovia, p. 1).4

Negotiations, therefore, were fading away by consumption without a strong will to lead them, although the Boundary Commission gathered data, advancing work and surveying the border. In 1909, after the Portuguese government had rejected a proposal to carry out the delimitation by fragments, consent was obtained for the International Boundary Commission to begin the demarcation agreement. In 1911, the Spanish delegation presented a draft delimitation convention starting from the point where the 1864 Treaty ended: from the confluence of the Caya and Guadiana to the mouth of the Guadiana in the Gulf of Cádiz. That agreement therefore included the border of the territory of Olivenza, although it prudently omitted to name it. Furthermore, the project was based on the traditional border in those parts that did not give rise to discussion. The project was put on hold until 1913, when the Portuguese delegation studied it; however, with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, progress was again suspended. Once the war ended and normality was restored, it was agreed that the negotiations over Olivenza would continue to be of great concern to Portugal. In 1920, the decision was finally made not to include the area in the future Convention of Limits. Instead, a treaty was concluded at long last. The work on delimitation would begin in the area between the Caya and Cuncos. Once the Boundary Commission was able to resume its work, a counter draft treaty was written in 1924. In 1926, when the Convention of Limits on the southern part of the border was signed, it was again mentioned that the question of Olivenza remained unanswered. On the Spanish side, the Treaty of 1801 had settled the question of possession and expressly designated the course of the Guadiana as the border. The Spanish Commission also argued that it would be imprudent and reckless for Spain to expect the Portuguese to definitively relinquish Olivenza. It was not until 1932 when the difficulties in obtaining a modern boundary treaty delimiting the border on the Olivenza side were accepted, and since then, the discrepancy has not been dealt with internationally.

In addition to the case presented here on Olivenza, Spain is involved in other similar cases of changing sovereignty of spaces that hindered the definitive delimitation of the country: Gibraltar and Ceuta. In short, Spain controls the side attached to Morocco but not the side attached to Spain. Gibraltar came under the control of the United Kingdom after the Treaty of Utrecht (1715) and Spain has claimed sovereignty over it ever since. Ceuta, on the other hand, is a city whose sovereignty is disputed by Morocco. Portugal ceded Ceuta to Spain in 1668 under the Treaty of Lisbon.

2. Undivided spaces: contiendas

In areas with contiendas, which were areas of shared use between neighbours and where neighbours did not necessarily identify themselves with a state, the moment that the territory was divided, they automatically became part of the sovereign state. Those border divided areas have sometimes been theorised as dangerous places. Rajaram and Grundy-Warr (2007), for example, have argued that borders were created to protect the people living in border areas, and as we have seen, that was indeed the justification given for the delimitation of the border between Portugal and Spain on the grounds that it would bring harmony to the area. From the point of view of governments, border areas can also be understood as areas of power where the meaning of national identity is created and questioned (Ranjan, 2018).

In the case study presented herein, the top cause of the disputes was the attempt to establish boundaries between the different towns. Because the boundaries were not defined, each council wanted to have as much of the territory as possible (Carmona, 1998). Of the three contiendas identified - Villanueva del Fresno, Valencia de Mombuey and La Contienda -, only the last one was relatively difficult to delimit. The larger areas of the Contienda of Villanueva del Fresno and Valencia de Mombuey were designated as Spain and incorporated into Article 2 of the Agreement of 29 June 1926. A special agreement had to be signed for the division of the Contienda, on 27 March 1893, and was later incorporated in Article 7 of the 1926 Agreement.

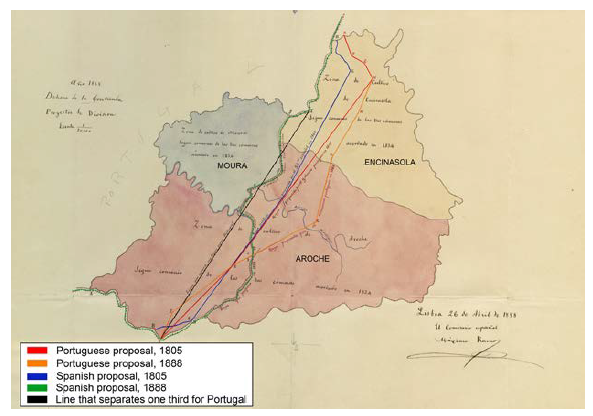

La Contienda was an area disputed by both kingdoms and affected the towns of Aroche, Moura and Encinasola. The starting point of the conflict dates to the thirteenth century, when the Treaty of Alcañices was signed and Aroche became part of Castile and Olivenza part of Portugal. The signing of that treaty sought to avoid the existing conflicts in that part of the Iberian Peninsula located on the border. At the end of the fifteenth century the conflicts resurfaced and continued until the signing of La Concordata in 1542, which established a demarcation between the towns of Moura, Aroche and Encinasola. The representatives of both monarchs expressed their conviction that it was necessary to reach an agreement, and the first demarcation was made between those three towns. The territory was ordered to be divided between the rival communities, although the most controversial area, La Contienda, was left for common use. That resolution, which was extremely long and detailed, also included rules for the administration of the territory for common use and prohibited activities requiring exclusive possession, including cultivating the land and constructing buildings. The agreement clarified that Encinasola had the same rights of use in La Contienda as the other two communities but lacked jurisdiction. Whether the contested territories were Spanish or Portuguese was never addressed. While La Concordata divided the rights of the inhabitants, it did not seek to affect those of their country, thereby allowing the monarchs of both Spain and Portugal to retain their dominions intact, as if the territory had never been subject to debate or division.

As an end to those disputes, and as shown here, the way in which the states culminated those cross-border disputes was via various treaties (fig. 2), and the way in which they reached that point was by eliminating all the border areas of an agro-silvo-pastoral nature that gave rise to conflicts between the communities (García-Álvarez, 2019). Once that problem was resolved, the southern part of the border between Portugal and Spain was completely defined and with clear jurisdiction. The security of the borderlanders thus prevailed. The exception is Olivenza, which despite not being considered in the 1926 Convention of Limits, for Spain is accepted to end at the Guadiana, as was agreed upon in 1801. Portugal claims sovereignty by the Treaty of Badajoz because Spain breached the terms of this treaty when it invaded Portugal in 1807 and by the signing of the Treaty of Vienna.

V. Conclusion

This article has offered an analysis and review of the translation of governments’ efforts to delimit their territories in the nineteenth century by the new concept of sovereignty that emerged in Europe, which generated contiendas or fuelled certain cross-border conflicts along the border between Portugal and Spain, including in Olivenza. The aims of the treaties signed throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were clear: to reinforce state control over the borderlands, to end territorial conflicts between frontier communities and to stamp out smuggling.

In relation to disputes, the first circumstance to bear in mind is that if a border conflict exists, it is because a border exists. That reality has an imminently geopolitical character and is of great interest in the structuring of states and nations. As shown herein, the border delimits the space over which the state exercises its power with full sovereignty and, as a rule, represents the physical delimitation of national identity. Under treaties, the boundary is delimited, and boundary disputes are quite often, if not always, about divergent interpretations of those titles and thus relate to the boundary’s exact location. Even if the concept of boundary determines the territory, territories are dynamic and cannot disappear. Moreover, they are changeable because of their social construction, which encompasses legal instruments such as treaties, conventions and/or political strategies. As explained, the Boundary Commission drew, modified, and erased them according to their own will, the will of the states or the historical documentation that they consulted. Nevertheless, the border did not disappear but was adapted to an agreement according to both parties. For that reason, since the signing of the first treaty in 1864, which delimited the border from the mouth of the Minho to the confluence of the Caya and Guadiana, the rest of the border was to be delimited by taking the course of the Guadiana as a basis.

The primary reason why no global agreement emerged about the delimitation of the border between Portugal and Spain and why it was delayed was the territory of Olivenza. In disputes about territorial attribution, states prove their alleged right to the territory in dispute; in boundary delimitation disputes, however, the contending parties agree on the existence of a boundary but disagree on its location. Nonetheless, in both types of disputes, the result that states seek is the same: the expansion or maintenance of their sovereignty and thus their territory (and their boundaries). However, though Olivenza was not incorporated into the 1926 Convention of Limits, it does not mean that there is no dispute in the southern part of the frontier. Today there are associations that actively fight for the return of Olivenza to Portugal, such as the Grupo dos Amigos de Olivença-Sociedade Patriótica, founded in 1938. Although at first sight this issue does not seem to affect the border, nor does it seem to have a direct bearing on the influence of politics, it causes disturbances in Portuguese-Spanish relations.

Last, the borders that emerged in the nineteenth century were not only the result of sovereignty but also marked a before and after situation because of the stabilisation that they achieved and because of the exact definition of the borders of states in accordance with the new concept of territoriality. The emphasis of this article lies in the historical importance of that phenomenon in the border between Portugal and Spain, especially in its southern part, which is rarely dealt with in academic and other current literature.