Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Silva Lusitana

versão impressa ISSN 0870-6352

Silva Lus. vol.21 no.2 Lisboa dez. 2013

Forest Intervention Areas (ZIF): A New Approach for Non-Industrial Private Forest Management in Portugal

Zonas de Intervenção Florestal (ZIF): uma nova abordagem para a gestão de áreas florestais privadas de pequena dimensão em Portugal

Zones d'Intervention Forestière (ZIF) une nouvelle approche de la gestion des zones forestières privées de petite dimension au Portugal

*Sandra Valente, **Celeste Coelho, ***Cristina Ribeiro e ****João Soares

*PhD. Student at the Doctoral Programme in Environmental Sciences and Engineering, Department of Environment and Planning, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 AVEIRO. Research Assistant, Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e do Mar (CESAM). E-mail: sandra.valente@ua.pt

**Full Professor, Department of Environment and Planning, CESAM, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 AVEIRO. E-mail: coelho@ua.pt

***Research Assistant, Department of Environment and Planning, CESAM, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 AVEIRO. E-mail: cristinaribeiro@ua.pt

****Research Assistant, Department of Environment and Planning, CESAM, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193 AVEIRO. E-mail: jsoares@ua.pt

ABSTRACT

This research contributes to the discussion regarding Forest Intervention Areas (ZIF) in Portugal, analyzing the technical and social perspectives on the potential and constraints of this approach. The size of forestry holdings, the constraints of individual management, the abandonment of rural areas and the frequency and intensity of forest fires in Portugal have stressed the need to strengthen cooperation and organization of small-scale forest owners and producers into a joint strategy for rural resources management. ZIF approach is recognized by technical and political stakeholders as a promising approach for the management of small-scale forest holdings. At local level, ZIF approach was already disseminated, gaining the trust and cooperation of forest owners. However, the absence of effective results is leading to an increasing distrust amongst forest owners and ZIF members.

Key words: forest management, small forest properties, forest stakeholders, ZIF

SUMÁRIO

Esta investigação contribui para a discussão em torno das Zonas de Intervenção Florestal (ZIF) em Portugal, analisando as perspetivas técnicas e sociais face às potencialidades e constrangimentos deste modelo de gestão. A estrutura da propriedade florestal, as dificuldades de gestão individual, o abandono do mundo rural e a frequência e intensidade dos grandes incêndios florestais em Portugal têm salientado a necessidade de reforçar a cooperação e a organização dos pequenos proprietários e produtores florestais para uma estratégia conjunta de gestão dos recursos rurais. O modelo de gestão ZIF é valorizado pelos agentes técnicos e decisores políticos como uma estratégia promissora de gestão do minifúndio florestal. Ao nível local, a disseminação das ZIF levou à aceitação e cooperação dos proprietários florestais. Contudo, a ausência de resultados efetivos está a dar lugar a uma descrença generalizada entre os proprietários florestais e os aderentes das ZIF.

Palavras-chave: gestão florestal, minifúndio florestal, agentes florestais, ZIF

RÉSUMÉ

Ce travail de recherche apporte sa contribution à la question des Zones d'Intervention Forestières (ZIF) au Portugal, en évaluant les perspectives techniques et sociales face aux potentialités et aux limitations de ce modèle de gestion. La structure de la propriété forestière, les difficultés de gestion individuelle, l'abandon du milieu rural ainsi que la répétition et l'intensité des incendies de forêt au Portugal ont mis en évidence la nécessité de consolider la coopération et l'organisation des petits propriétaires et producteurs forestiers par la mise en place d'une stratégie commune de gestion des ressources du milieu rural. Au niveau local, la dissémination des ZIF a rencontré lacceptation et la coopération de nombreux propriétaires forestiers. Cependant, l'absence de résultats concrets a décrédité les modèles ZIF auprès de propriétaires forestiers et des adhérents.

Mots-clés: gestion des forêts, forêt de petite dimension, acteurs forestiers, ZIF

Introduction

Agriculture and forestry were for a long time the main economic activities of Portuguese rural areas (MADRP, 2007). These activities have suffered major changes during last century, boosted by a continuous process of rural depopulation and ageing. Since the end of the 19th century, the area occupied by forest has increased from approximately 7% to 35%, occupying former agricultural lands (COELHO, 2006). The abandonment of agricultural lands and the consequent forest and shrubland encroachment into those lands were partly responsible for the occurrence of intense wildfires in north and central regions of Portugal (DGRF, 2007).

One significant characteristic of the Portuguese forest is the weight of Non-Industrial Private Forest (NIPF) owners, who are responsible for more than 75% of the forest. The small size of forest properties is one of the major constraints of forest management, especially in north and central Portugal. This situation is due to the continuous subdivision of relatively large properties into smaller ones, most of the times by division of inheritance.

Various authors have been arguing about the disadvantages of forest management at individual scale, enhancing the role of cooperation of forest owners (KITTREDGE, 2003; KITTREDGE, 2005; RICKENBACH et al., 2005; MARTINS and BORGES, 2007). The main arguments supporting landowners cooperation are related with the increase of competitiveness of small ownerships, the promotion of non-monetary benefits of forest (aesthetics, biodiversity, soil protection, among others) and the sharing of information and equipment, etc.

Forest owners' cooperation and organization is increasing since the 1990s, influenced by the national policy and by the work of FORESTIS – The Forest Association of Portugal - which is a non-profitable organization founded by forest owners and forest technicians, aiming to promote and support the constitution of Forest Producers Organizations (OPF) at local level (FELICIANO, 2012). The OPF is an important vehicle for the implementation of forest policy in NIPF areas (MENDES, 2007a; MENDES 2007b, SILVA et al., 2008; FELICIANO, 2012). From 2000 to 2013, the number of OPF has increased more than 150%. The OPF are particularly relevant in the north and central Portugal, mainly occupied by small-scale holdings (MENDES, 2007a; MENDES, 2007b).

But there are still several constraints to cooperation, which in Portugal have been related with the fear of losing land tenure, the landowners' absenteeism (MARQUES, 2011) and also the lack of successful previous experiences (MARTINS and BORGES, 2007). However, by joining and acting together, the NIPF owners will have a say in forestry matters and especially in what concerns the policy decision-making (FELICIANO and MENDES, 2011).

ZIF emerged in 2005 as a promising tool for dealing with many of those aspects, being especially envisaged to plan and to manage forests at larger spatial scales. ZIF approach provides an opportunity to NIPF small owners' cooperation. However, its implementation relies on the acceptance and cooperation among forest owners and producers as well as on the technical and financial support provided by governmental organizations (GO) and non-governmental organizations (NGO).

This research contributes to the debate surrounding the challenges and opportunities of ZIF approach, aiming: i) to understand ZIF concept; ii) to assess ZIF process evolution; and iii) to analyse the technical-institutional and social perspectives about ZIF approach. After analysing ZIF national framework and evolution, the institutional and social perceptions will be evaluated in a case study located in the central region of Portugal.

Forest Intervention Areas (ZIF)

Origin and concept

ZIF approach is integrated in the restructuration of the Portuguese legal and institutional framework for forest management and for Forest Protection against Fires (DFCI) after the 2003 catastrophic wildfires. ZIF law was issued in 20051 and amended in 20092. Each ZIF is a continuous and bounded area, where the main land use is forest. These areas can include private land, common land (baldios) and public land, but the two latter types of land were only included in the 2009 legislation. ZIF constitution in private areas has to fulfil three criteria: i) to include at least 750ha; ii) to include a minimum of 50 forest owners or producers; and iii) to include at least 100 properties.

The main objectives of ZIF approach are: i) to promote Sustainable Forest Management (SFM), following the national and regional guidelines and regulations; ii) to mitigate current constraints to forest intervention, namely land structure and size; and iii) to develop structural measures to DFCI. It is expected that ZIF implementation provides major benefits concerning the intervention in larger spatial scales and ensures a better and more coherent strategic vision for rural areas (DEUS, 2010).

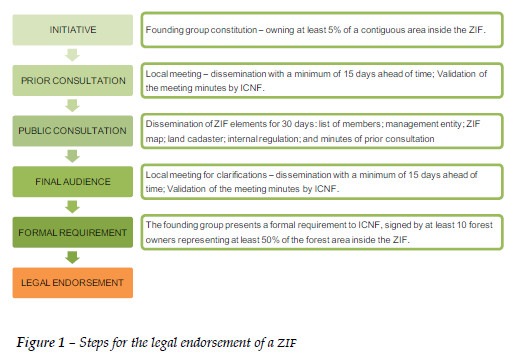

ZIF process is constituted by three major stages: the legal procedure; the planning stage; and the implementation stage. The first stage concerns all legal requirements needed to ZIF endorsement (Figure 1). The process can be initiated by a group of forest owners or producers, creating the founding group. This group has to own at least 5% of a continuous area inside the ZIF. The founding group promotes local meetings, aiming to disseminate ZIF approach and to encourage other landowners to join, and prepares all the necessary elements to make the formal requirement to ZIF constitution to the Institute for the Conservation of Nature and Forests (ICNF).

Each ZIF is managed by a single entity, which can be a non-profit-making and voluntary organization or a forest enterprise approved by the landowners and producers. The management entity will administer ZIF territory and is responsible for defining ZIF plans. The mandatory plans are: i) the Forest Management Plan (PGF), indicating the forestry operations and the activities within ZIF area, according to the guidelines of the Regional Forest Plan (PROF); and ii) the Specific Plan for Forest Intervention (PEIF), defining actions to protect forest against biotic and abiotic risks. The ICNF has to approve the plans and should support and monitor ZIF activities. PEIF term is five years and PGF term is 25 years.

The third stage is the implementation of the interventions and actions defined in the planning tools by forest owners and producers. The landowners can also decide to attribute full responsibility of ZIF administration to the management entity, who becomes in charge of all ZIF components (e.g. forestry, agriculture, grazing). ZIF costs should be supported by their members, through a common fund to implement actions for mutual benefits (e.g. financial contributions of forest owners, revenues, prizes, etc.), and by the national and European financial instruments. ZIF implementation has been facing some constraints, such as the high implementation costs3, the difficulty to get funds, the complexity to assemble small-scale holdings and landowners and the social resistance to the approach, which is related with landowners' fear of losing their tenure rights.

The active involvement of landowners in all ZIF stages is a key-factor for its success (MARTINS and BORGES, 2007). Several informing sessions and public meetings have to take place to make landowners become ZIF members. The involvement in later phases is not clearly defined and could represent a major bottleneck to ZIF progress. Despite the major strengths of this approach, the complexity and bureaucratic process behind it represent weaknesses and limiting factors to the private investment.

National overview

Concerning NIPF areas, the lack of land registry and the prevalence of small-scale holdings in north and central Portugal, emphasized that «...it is necessary to determine the minimal management areas and systems for joint management, but these depend on the attitudes of the owners» (DGRF, 2007: 35). As such, one of the major objectives of the national forest policy is to promote small-scale forest owners' cooperation into a joint management of their forests (AFN, 2011) and ZIF approach was especially conceived to fulfil this aim.

From 2005 till the end of 2012, 162 ZIF were endorsed, representing more than 845 000ha of land and corresponding to 24% of the national forest areas. Maritime pine, Quercus suber and eucalyptus areas are the main species in ZIF territories (AFN, 2011). These figures conceal the real numbers of ZIF social acceptance. The formal requirement to ZIF endorsement does not demand the involvement of all forest owners inside ZIF territory, and the membership rate is around 50% (DEUS, 2010).

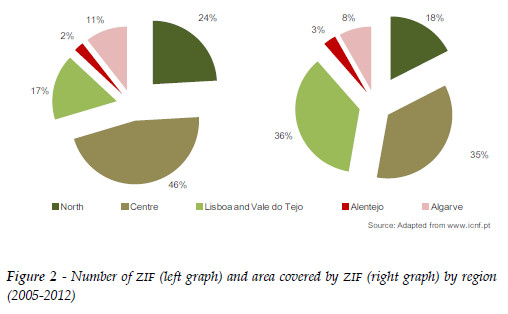

If we take the number of ZIF into consideration, the larger dynamism lies in the central region of Portugal, followed by the north region (Figure 2). However, the results are substantially different when the main variable of analysis is land area covered by ZIF (Figure 2). This is related with the size of the ownerships, being much more difficult to obtain larger ZIF in areas occupied by small-scale holdings.

There are 299 000ha covered by 75 ZIF in central region, which means that the medium size of each ZIF is less than 4 000ha. On the other hand, Lisboa and Vale do Tejo has 300 000ha covered by 27 ZIF and the medium size of a ZIF is above 11 000ha. The analysis of ZIF dimension also highlights the huge weight of ZIF with less than 1 500ha in central and north regions, representing 25% of the total. By comparison more than 33% of Lisboa and Vale do Tejo ZIF are larger than 10 000ha.

After the legal endorsement of the first ZIF in November 2006, the evolution has been very uneven. There was a continuous increase from 2006 to 2009, either in the number of ZIF or in the area covered by ZIF. In 2010, a huge downturn was felt, which was probably linked with the political changes and the internal economic crisis, which affected not only the organization of the sector but also the availability of public funds to ZIF constitution and implementation. In 2011, despite the low number of ZIF, the area covered by ZIF exceeded 200 000ha. So far 2012 was the worst year in terms of ZIF performance.

ZIF approach is evolving in an unorganized and confusing way, revealing several advances and regressions. Additionally, ZIF are also being constituted in areas with low fire hazard, occupied by medium holdings and where a professional management is already in place (DEUS, 2010). The presence of private industrial forest areas in ZIF is also increasing, especially conceived for economic purposes with rapid growth species (DEUS, 2010). Both situations are favourable to the national figures, but can also move away from the ZIF objectives.

The National Forest Authority (AFN) report indicated the existence of 18 841 members in 143 ZIF. This figure shows that inside each ZIF, there are still many forest owners who did not join this initiative (AFN, 2011). This goes in line with DEUS (2010) findings, indicating that the main difficulty in ZIF constitution was to assemble the minimum number of forest owners and holdings. In 2012, there were 52 OPF, seven private enterprises and five local development associations as ZIF management entities. Almost 90% of the ZIF are managed by OPF, either existent or created for this purpose. Half of the ZIF management entities is only responsible for one ZIF and 36% is responsible for less than five ZIF.

Despite the existence of more than 150 ZIF already promulgated, ZIF further stages, such as the definition and approval of PGF and PEIF and their implementation, show the slowness and weaknesses of this process. In fact, the majority of ZIF management entities have not elaborated the PEIF and the PGF, delaying implementation, which is also related with delays in public funds availability (DEUS, 2010).

Research design

To evaluate the social and technical perspectives over ZIF approach, empirical data was collected from different stakeholder groups: national decision-makers and technicians; local decision-makers and technicians; forest owners; and other citizens. The questions addressed in this paper concerns the policies and tools available for forest management, with special focus to ZIF approach.

Case study selection

The municipality of Mação is located in the central region of Portugal, more precisely within a transition zone between the densely populated coastal regions and the depopulated interior areas. At the beginning of the 20th century, the municipality had a highly diversified landscape supporting a variety of activities, including subsistence farming (e.g. olive production), grazing of sheep and goats and other forestry practices (e.g. timber production and resin extraction). In the 1950s and 1960s, large-scale migration to Lisbon resulted in severe depopulation and a general abandonment of traditional activities. Rural abandonment together with the encroachment of former agricultural and grazing lands by maritime pine natural regeneration and eucalyptus plantations, contributed to increase Mação vulnerability to forest fires and to desertification.

Mação was selected as a case study due to the following reasons: i) was severely affected by wildfires in the last decades; ii) is one of the Portuguese pilot areas to fight desertification; iii) several infrastructures and technologies to DFCI were implemented in the last decades, such as water points, watch towers and a MACFIRE – System to monitor forest fires, a network of fire-breaks and paths and, more recently, implementing a network of strips for fuel management; iv) has been involved in several research projects concerning desertification and forest management, with a strong component of stakeholder participation; v) was a precursor municipality in supporting and implementing ZIF approach; vi) has five endorsed ZIF; and vii) represents an example of close collaboration between internal and external stakeholders.

In 2011, there were 7 338 inhabitants living in the Mação municipality, representing a decrease of more than 65% of the resident population since the 1950s. The socio-economic context in Mação is also responsible for some of the major land use changes occurred in the last decades. Forest land, mainly composed by areas of Pinus pinaster and Eucalyptus globulus, occupies 21 419ha, which corresponds to more than 50% of the municipality territory. Shrubland is also quite important, occupying 34% of the municipality land use. Burned area, with low or no vegetation, represents 18% of the forest land.

Mação region has undergone severe drought periods, associated to long, dry and hot summers, resulting in catastrophic wildfires, which destroyed large areas of forest and shrubland. In 2003, wildfires consumed 18 134ha of forest (around 85% of the municipal forest area) and also around 10% of the shrubland (AFN, 2010). Some areas have burned twice in a five year period, developing irreversible processes of vegetation and soil degradation (VALENTE et al., 2011).

Since 2003, local organizations (e.g. City Council, parishes, forest association and other NGO) have been supporting ZIF approach. The municipality was divided in 29 ZIF (Figure 3), but so far only five were endorsed (7 300ha). The initial enthusiasm with ZIF constitution, not only in Mação but at national level, should move to the accomplishment of progresses in the ZIF already endorsed.

Methods and sampling

In order to assess social, political and technical perceptions about ZIF approach, some questions about: i) forest management policy, tools and measures; ii) knowledge about ZIF approach; iii) agreement and acceptance of ZIF approach, were included in the social perception survey carried out in the municipality of Mação. The questionnaire was implemented during 2010 (first phase) and 2012 (second phase) by trained interviewers. National technicians were sent a survey by e-mail.

The survey integrated national and local technicians and a sample of 5% of the inhabitants living in the Mação municipality. The sample included 353 respondents, between 13 technicians from national and regional entities, 17 technicians and other stakeholders from local GO and NGO and 323 inhabitants from Mação municipality. The inhabitants sample was proportionally distributed by residence area, age, gender, schooling and livelihood. The differences between forest owners (N=208) and other inhabitants (N=115) were also analysed. Data was analysed using PASW Statistics 18 software, through frequency and cross-tabulations and bivariate analysis, particularly the Chi-square test of independence.

Additionally, eight local key-stakeholders, representing the City Council of Mação, the Forest Association of the municipality of Mação - AFLOMAÇÃO, three parishes' councils and three ZIF founding groups were interviewed concerning their opinion and participation in ZIF process. The interviews were applied to each respondent individually and data was analysed qualitatively, using quotations from the interviews.

Results

This section highlights the awareness about national and regional guidelines for forest management, by analysing technicians and civil society knowledge on policy and legal tools. Particular emphasis is given to ZIF approach and its development in the Mação municipality.

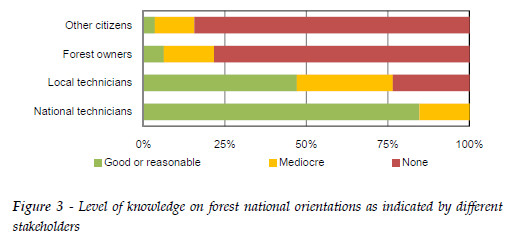

Knowledge on forest management guidelines

The knowledge on policies and planning tools differed substantially according to the type of stakeholder. While above 60% of the national technicians knew well the national orientations to forest management, only less than 25% of the local technicians referred to know well these orientations, but almost 60% have an idea about them. Above 80% of the respondents from local population (both forest owners and other citizens) were not aware of the national policies or guidelines to forest management (Figure 3).

The standard chi-squared test of independence provided evidence to reject the null hypothesis of no association between the two major stakeholder groups - i) national and local technicians; and ii) civil society, including forest owners – and policy knowledge (x2(2) = 117,72, p  0,05). This was expected, as the background of many technicians and decision-makers is forest engineering or forest sciences and some of them have participated or are responsible by national policy-making. Civil society was not aware or informed about policy issues. From the local population only three respondents referred to know quite well the national orientations for forest management, corresponding to young women with a university degree.

0,05). This was expected, as the background of many technicians and decision-makers is forest engineering or forest sciences and some of them have participated or are responsible by national policy-making. Civil society was not aware or informed about policy issues. From the local population only three respondents referred to know quite well the national orientations for forest management, corresponding to young women with a university degree.

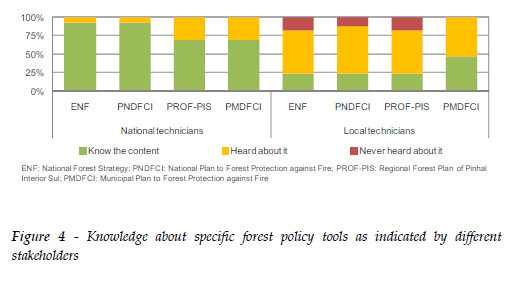

National and local stakeholders were also asked to classify their knowledge about specific policy and planning tools. The results showed that the majority of the respondents from national entities were familiar with the content of all documents (Figure 4). Local technicians had heard about all documents, but only around 25% knew their content (Figure 4). The regional and municipal plans were less known by national technicians and the Municipal Plan to Forest Protection against Fire (PMDFCI) was the most known tool among local technicians, as it is a specific plan of Mação municipality (Figure 4).

ZIF origin, dissemination and acceptance

The type of forest in Mação municipality represents the target area for using ZIF approach. As stated by AFLOMAÇÃO, «to assemble properties into management units in a municipality shredded in 80 000 agricultural and forestry properties, distributed by more than 15 000 land owners (amongst which 50% do not live in the municipality) is essential». The rural depopulation together with the size of the holdings resulted in land abandonment, which will not be reversed unless a new model of management is implemented, as stated by some of the interviewees:

«It is not possible to make forestry with 200 square meters, with less than half hectare» [ZIF stakeholder].

«If we had here larger areas, the leap in terms of the type of exploitations might have been given, from familiar to business type, and settle some rural population. This did not happen because there was no dimension or scale for that» [Local GO stakeholder].

ZIF approach is, though, an opportunity to constitute larger management units, as it is highly supported by local stakeholders:

«...the concept [of ZIF] was born in 2003, before the country even speak about it. After the discussion raised in 2003 (...) we started to make pressure, other persons started to make pressure and the former General-Directorate of Forests has created the ZIF law» [Local GO stakeholder].

«...the thought was focused on the need of maintaining the territory alive and for that the territory has to be productive. To be productive, it has to address some criteria and to be effectively managed and that demands to find a tool to organize people to do that» [Local GO stakeholder].

The ZIF constitution process in Mação started right after the law publication in 2005 and was led jointly by the City Council of Mação and by the AFLOMAÇÃO, through the organization of meetings in several villages, aiming to inform forest owners and making them to believe and embrace this initiative. Several other local stakeholders (e.g. parish council chairmen, members of the opposition political party and other key-stakeholders) joined this process:

«I became enthusiastic with the idea. We made a map of the parish and during Carnival holiday we have started to make the contacts. My role was to contact all forest owners, know who they are» [ZIF stakeholder].

The acceptance of ZIF approach among local communities, and especially among forest owners, is an essential element. The first reaction of forest owners when approached with the idea was described as positive by the interviewees, confirmed by the fast endorsement of five ZIF. Even the most reluctant forest owners ended up joining ZIF, as illustrated by the next quote:

«I remember some farmers saying 'only over my dead body' but then after a second fire, they became receptive to all ideas» [Local GO stakeholder].

«...almost all people joined, we had just two or three more difficult cases. They were young people, which did not want to join and also did not want other to join» [ZIF stakeholder]

«From the approached forest owners, everyone accepted, became excited and even helped. They were on the meetings and some of them even came from Lisbon with only 0,5ha of land. The affective value and the aim behind ZIF approach led to the participation» [ZIF stakeholder].

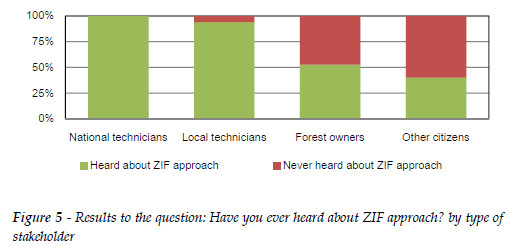

The standard chi-squared test of independence provided evidence of an association between the type of stakeholder and the knowledge about ZIF approach (x2(3) = 30,78, p  0,05). The results from the survey highlighted the high awareness amongst national and local technicians about ZIF, where all technicians, except one, have recognized ZIF approach (Figure 5).

0,05). The results from the survey highlighted the high awareness amongst national and local technicians about ZIF, where all technicians, except one, have recognized ZIF approach (Figure 5).

Half of the inhabitants surveyed also referred to have heard about ZIF approach (Figure 5), but only 31% were able to define what is a ZIF, highlighting the following aspects: i) group of forest small-scale holdings; ii) assembling forest owners into a common management of land; iii) land management by a single entity. ZIF recognition was higher in forest owners group than for the other citizens (Figure 4). From the inhabitants who recognized ZIF approach (156 respondents), 51% referred to have been informed by local technicians and 37% by their family, neighbours or friends.

The recognition of ZIF approach was higher in the parishes where there are ZIF constituted, such as Ortiga (ZIF Ortiga), Mação (ZIF Castelo), Penhascoso (ZIF Penhascoso Norte), Amêndoa (ZIF Aldeia de Eiras) and Envendos (ZIF São José das Matas). This was confirmed by the standard chi-squared test of independence providing evidence of an association between the residence of forest owners and other citizens and the knowledge about ZIF approach (x2(7) = 26,31, p  0,05). The same was concluded between high levels of literacy and knowledge about ZIF approach (x2(5) = 51,36, p

0,05). The same was concluded between high levels of literacy and knowledge about ZIF approach (x2(5) = 51,36, p  0,05).

0,05).

Concerning national and technical technicians, more than 60%, both from national and local level, have participated in ZIF approach The national technicians participated in the definition of the legislation and half of them also participated in landowners' awareness (mainly through public presentations), in the definition of ZIF plans and in the financial support to the process. The local technicians were mainly involved in awareness and dissemination, organizing meetings for ZIF constitution and contacting landowners through door-to-door approaches.

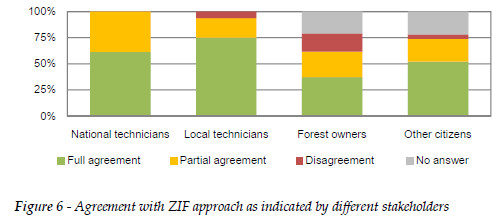

The level of agreement with ZIF approach was very diverse according to the type of stakeholder (Figure 6). Most of the national and local technicians agreed with the approach. Eight technicians referred however some elements that should be improved in ZIF approach, such as increasing forest owners' participation and simplifying the bureaucratic and legal procedure of ZIF.

The answers of forest owners and other citizens concerning agreement with ZIF approach were not as positive as the one from the technicians (Figure 6). In fact, only 37% of the forest owners, who have recognized the ZIF, totally agreed with it and 25% agreed partially. This last group has identified as elements of disagreement the loss of tenure rights, the increase of social imbalances between adherents and non-adherents and the economic constraints and bureaucracy. As previously mentioned, only 40% of the other citizens have recognized ZIF approach, and most of them seem also to agree totally or partially with it. Almost 25% of the forest owners and other citizens did not answer to this question and 13% of the forest owners referred to disagree with ZIF approach.

The major level of unfamiliarity and disagreement with ZIF approach was found in Carvoeiro parish respondents. In fact, Carvoeiro was the only parish in the Mação municipality which was not affected by forest fires in the last 20 years. In this sense, it is clear that forest owners still have a high economic interest in their properties and probably are not willing to join into a collective model of forest management. Moreover, Carvoeiro did not represent a priority area for ZIF constitution, being clear a lower awareness when compared to the other Mação villages.

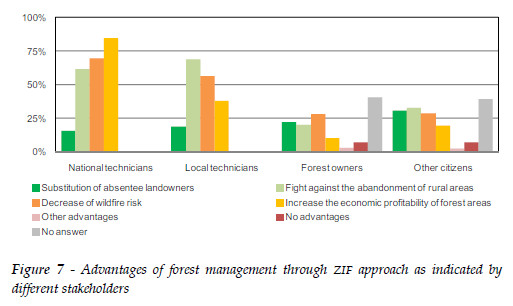

ZIF advantages and disadvantages were also addressed in the questionnaire. It is important to refer that around 40% of the inhabitants that recognized ZIF approach did not mentioned any advantage or disadvantage Figure 7; Figure 8). The main perceived advantages of ZIF were linked with the need to mitigate forest fires and to fight rural abandonment (Figure 7). National and local technicians have also mentioned that forest management through ZIF model has the potential to increase the profitability of forest areas. Some stakeholders from all groups have also identified as an advantage the possibility of substituting the absentee landowners (Figure 7). This advantage was the main concern for respondents who were members of a ZIF.

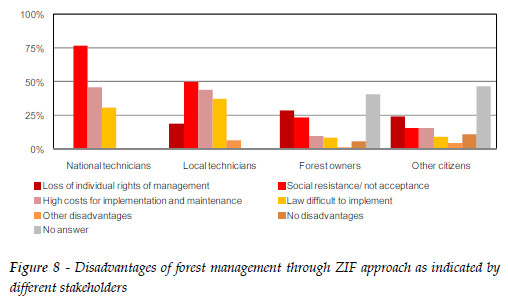

Social resistance and landowners' non-acceptance of ZIF approach was considered a major disadvantage by national technicians (identified by more than 75%) and by local technicians (identified by 47%). Other disadvantages pointed out by technicians were the high costs of implementation and maintenance of a ZIF and the complexity of the law (Figure 8). For forest owners and other citizens, the disadvantages indicated were related with the loss of individual rights of management, identified by a quarter of these respondents (Figure 8). This aspect was even referred by 23% of the respondents integrated in a ZIF. This result demonstrated that some aspects of ZIF approach were still unclear, since individual producers can adhere to a ZIF and still maintain the individual management of their properties, contributing only to the common activities, such as the DFCI measures.

Since the publication of the first ZIF in the municipality of Mação in 2007, no major progresses towards implementation were made, mainly due to the absence of financial capacity of forest owners, being very dependent from EU and/or from national incentives. The interviewees' discourses also emphasized the funding as a central cause for ZIF approach failure:

«Almost all the ZIF we have here were made with people accepting the concept... and assuming that the government [national] would support around 80 to 90%, which was the political discourse since 2003» [Local GO stakeholder].

«... we are speaking of very high investments (...) because we know the people, in general forest owners do not have either the economic conditions, or the willingness (...) and either the process dies because there is no individual financing capacity, or we find new ways of gathering this money...» [Local GO stakeholder].

«There is no chance of having forest owners investing their money. The persons said take my land (...) when this gives something in return, I will be here...» [ZIF stakeholder].

This situation is causing the first signs of distrust about ZIF potential among local organizations and local communities. Additionally, local stakeholders stood up to ZIF solution, convincing people to believe and accept this idea. Fearing to waste all the work done so far, if nothing happens in a near future, the idea of ZIF pilot area seems to be the way out:

«ZIF pilot area working. If people could see what is being done and what would be the profits... And it is quite likely that after seeing a good example, people will say that their contribution will be something more [more than the land], even work force. It could be a way of attracting people» [Local GO stakeholder].

Discussion

Portuguese forest sector, mainly owned by NIPF owners, has been described as fragmented, dispersed and heterogeneous (MENDES, 2003). As such, a potential solution would be to embrace a collective learning process, both in civil society and in their organizations (MENDES, 2003; 2008). This is already occurring in many parts of the world, materialized in joint efforts of State and civil society to manage forest (e.g. WOLLENBERG et al., 2006; JANSE and KONIJNENDIJK, 2007; NAIL, 2008).

Rural areas abandonment promoted a new rural landscape, stressing the need of forest owners' cooperation, guaranteeing the appropriated spatial scale to make rural interventions profitable, strategic and benefiting from economies of scale (KITTREDGE, 2003; KITTREDGE, 2005; RICKENBACH et al., 2005; MARTINS and BORGES, 2007). In Portugal, and especially in north and central regions, small-scale forest holdings are dominant and forest has been a result of individual interventions and actions performed by forest owners, who have diverse interests and capacities. In fact, many small-scale forest owners perceive that the only viable option is no intervention (RADICH and BAPTISTA, 2005). This was also demonstrated in a survey4 carried out in a small parish of central Portugal about forest owners interventions after fire. However, since the 1990s many organizations are in place and are able to help, especially small-scale forest owners, in adopting new forms of forest management.

This leads to the central topic of this study – ZIF approach. Since the 1990s, several forest producers associations have emerged as a result of the State incentive to landowners' organization, but the State has not been able to differentiate the active and needed organizations, from the ones not able to promote forest management. After recurrent catastrophic forest fires, ZIF emerged as a promising tool for SFM in small-scale forest areas in Portugal (MARTINS and BORGES, 2007; MARQUES, 2011; SCHWILCH et al., 2012; VALENTE and COELHO, 2012; VALENTE et al., 2012).

The movement ZIF started in 2005 and, since then, the number of ZIF has been evolving unevenly, probably according to the public funds for ZIF constitution. The movement was especially visible in central region (46% of the ZIF are located in this region), where forest fires have been particularly intense and small-scale forest holdings are dominant. But many ZIF were also created in secondary regions, which are characterized by medium land holdings, with professional or industrial management (DEUS, 2010). Additionally, the landowners adherence to ZIF approach is not enough, as demonstrated by the analysis of ZIF national performance and in the survey carried in the municipality of Mação. From the discourses of the interviewed local stakeholders, this low adherence together with no financial incentives or fiscal benefits for the adherent forest owners represent risks to the whole process. The premature stage of implementation did not also allow to evaluate the real potential of this approach towards SFM and DFCI.

Although knowledge about the national guidelines, laws and tools is extremely important to establish effective ground-actions and interventions, our findings suggested that there is a generalized lack of knowledge about forestry policies and tools among civil society, and particularly among forest owners. This can probably be compensated by the technical capacity already installed in the OPF or in local GO, able to provide appropriated support to forest owners. In fact, the results from the survey demonstrated that part of the local technicians have already a good or reasonable knowledge of the strategic and national policy documents and planning tools for forest management and for DFCI. The ambiguous and instable feature of the legal and institutional framework of forest difficult the increase of social awareness about forest policy tools.

ZIF approach was clearly supported by national and local technicians in our survey, who recognized many advantages in implementing this type of management. A national-wide survey5 applied to Forest Technical Office (GTF) and to OPF has confirmed these findings, where the majority of forest technicians agree, totally or partially, with ZIF approach. If ZIF represents for local decision-makers and technicians the ultimate solution, for local communities this is still a quite unfamiliar issue. Almost half of the Mação's inhabitants included in the survey had heard about ZIF, but not everyone was able to explain it. This represents also one important aspect to be addressed in the future.

Our survey demonstrated that there was a reasonable acceptance of ZIF approach, and that the approached forest owners have reacted positively to the possibility of becoming ZIF members. However, the social resistance to ZIF approach and the landowners' fear of losing tenure rights were frequently mentioned as constraints to ZIF implementation. This goes in line with DEUS (2010) findings6, where ZIF management entities identified as the main difficulties of ZIF constitution to find forest owners and to make them embrace this initiative. SERBRUYNS and LUYSSAERT (2006) found similar resistance in Flanders (Belgium), where forest owners showed lack of interest in participating in forest groups, fearing to lose control over their land.

The definition of ZIF plans and their implementation are taking a long time, not only in Mação but in the whole country. The major part of the management entities has not elaborated the PEIF and PGF (DEUS, 2010). In Mação, some of the ZIF plans were elaborated, but there was a delay in the submission of the plans to the ICNF, because of insecurity concerning funds available to implement the measures. ZIF implementation and maintenance costs are quite high and were often mentioned by GO and NGO stakeholders as a major constraint. The initial enthusiasm about this approach and its potential is starting to fade due to the absence of an effective implementation of measures and actions. Several local stakeholders mentioned the need to implement a pilot ZIF to test, improve and disseminate the potential of this approach. This is related with the strong belief, among local organizations, on the ZIF potential, and with the need to increase trust and support amongst forest owners. ZIF law includes the need of creating a common fund to implementation from contributions of ZIF members. However, local stakeholders' discourses emphasize that forest owners do not have financial availability or will to invest their money in ZIF implementation.

The survey highlighted the low knowledge of civil society about legal tools and policies for forest management, where ZIF law is included. Land users are sometimes compelled to cope with policies and measures which exclude their visions and know-how and this could create constraints on the social acceptance and implementation of policies. This was already concluded in a previous study7(GALANTE et al., 2009), together with forest owners availability to receive more information concerning forest issues. A similar behaviour was found in forest owners in Flanders, Belgium, who were interested in receiving information and education about their forest (SERBRUYNS and LUYSSAERT, 2006). Better information and awareness will definitely contribute to a greater acceptance and trust in policy instruments as already demonstrated in some studies (SERBRUYNS and LUYSSAERT, 2006; DEUS, 2010). In the Mação municipality, several meetings were held to inform forest owners, however the survey highlighted that local communities know superficially ZIF approach. Even for ZIF members, it was observed that ZIF plans were developed by forest technicians with low involvement of forest owners. This passive involvement of landowners denotes the wrong idea that ZIF approach implementation only depends on landowners agreement in becoming members. NIPF owners have to be actively involved in all stages of ZIF approach, sharing decision-making power. This idea was also previously supported by other authors (e.g. MARTINS and BORGES, 2007; DEUS, 2010; MARQUES, 2011).

Conclusion

Small ownership and landowners' absenteeism is one of the major constraints to forest management in Portugal, which needs to be struggled by an increasing cooperation between forest owners. Therefore, achieving sustainability in small-scale forest areas will only be possible by moving from an individual decision making to a multiple decision framework (MARTINS and BORGES, 2007). ZIF approach apparently provides the legal setting needed to embrace that change and could represent the ultimate opportunity for small-scale forest areas in Portugal.

Technical and institutional perspectives over ZIF approach have been changing into a greater support of this type of management and many ZIF have been constituted by initiative of different local organizations. But ZIF constitution and implementation needs forest owners' acceptance and cooperation, technical support throughout the process and financial input at all stages. The social awareness about ZIF approach is still little, and it seems that only approached forest owners and who have participated in the meetings to ZIF constitution are aware of ZIF concept. Information and dissemination can be particularly relevant to increase trust and cooperation. Although many individuals did not recognize ZIF approach, landowners' acceptance of ZIF has been described as positive by local stakeholders. Nevertheless, social resistance to ZIF approach is frequently mentioned as constraint for moving forward. The endorsed ZIF in Mação are stagnated. The reasons behind this situation are related to financial constraints, either coming from public funds or from landowners' contributions. Public funds are suffering adjustments and small forest owners are lacking of money and will to invest in their own properties.

NIPF owners have to be actively involved in all stages of ZIF, namely discussing and negotiating ZIF plans and contributing to the implementation of all activities. Transparency, trust and investment are key-ingredients and will only be possible if forest owners are engaged throughout the whole process. To get ZIF out of this deadlock, interventions and actions foreseen on the ZIF plans need to be implemented. For that, the plans need to be submitted and approved, the public funds should reach on time to priority areas and forest owners need to be involved in the whole process, as a way of getting all type of support (financial, labour, know-how, etc.). If this does not work, ZIF will be just another lost opportunity, with misuse of public funds and discredit about forest owners' cooperation.

References

AFN, 2010. Apresentação do Relatório Final do 5º Inventário Florestal Nacional. Autoridade Florestal Nacional, Ministério da Agricultura, Desenvolvimento Rural e Pescas. [ Links ]

AFN, 2011. Caracterização das Zonas de Intervenção Florestal. Direcção Nacional de Gestão Florestal, Autoridade Florestal Nacional. [ Links ]

COELHO, C., 2006. Portugal. In J. Boardman and J. Poesen (Eds.), Soil Erosion in Europe. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Chichester, pp. 359-367. [ Links ]

DEUS, E., 2010. A implementação do conceito Zona de Intervenção Florestal em Portugal – o caso do concelho de Mação. Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Geografia Física, Ambiente e Ordenamento do Território. Coimbra: Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Coimbra. [ Links ]

DGRF, 2007. National Forest Strategy. Lisboa: Direcção-Geral dos Recursos Florestais. [ Links ]

FELICIANO, D., 2012. Indicadores de Eficácia de Organizações de Produtores Florestais. Silva Lusitana 20(1/2): 55-70. [ Links ]

FELICIANO, D., MENDES, A., 2011. Forest Owners' Organizations in North and Central Portugal – Assessment of Success. SEEFOR - South East European Forestry 2(1): 1-11. [ Links ]

GALANTE, M., ALVES, P.I., CAVACO, V., MIGUEL, M., 2009. A percepção da população portuguesa sobre Incêndios Florestais e as suas causas. In 6.º Congresso Florestal Nacional 6-9 October, Sociedade Portuguesa de Ciências Florestais, Ponta Delgada. [ Links ]

JANSE, G., KONIJNENDIJK, C.C., 2007. Communication between science, policy and citizens in public participation in urban forestry - Experiences from the Neighbourwoods project. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 6(1): 23-40. [ Links ]

KITTREDGE, D., 2003. Private Forestland Owners in Sweden: Large-Scale Cooperation in Action. Journal of Forestry, March: 41-46. [ Links ]

KITTREDGE, D., 2005. The cooperation of private forest owners on scales larger than one individual property: international examples and potential application in the United States. Forest Policy and Economics 7: 671-688. [ Links ]

MADRP, 2007. Plano Estratégico Nacional Desenvolvimento Rural (2007-2013). Lisboa: Ministério da Agricultura, Desenvolvimento Rural e Pescas, 84 pp. [ Links ]

MARQUES, M., 2011. Cooperação na gestão florestal: O caso das Zonas de Intervenção Florestal. Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Engenharia Florestal e dos Recursos Naturais. Lisboa: Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa. [ Links ]

MARTINS, H., BORGES, J.G., 2007. Addressing collaborative planning methods and tools in forest management. Forest Ecology and Management 248: 107-118. [ Links ]

MENDES, A., 2008. Política florestal em Portugal depois de 2003. In: J.S. Silva, E. Deus and L. Saldanha (Eds.), Incêndios Florestais 5 anos depois de 2003. Liga para a Proteção da Natureza, Autoridade Florestal Nacional, Coimbra, pp. 67-76. [ Links ]

MENDES, A., 2007a. Forest Owners' Organizations in Portugal: Are the infant going to survive? In: Proceedings of IUFRO 3.08 - Small-scale forestry and rural development: The intersection of ecosystems, economics and society. Galway: Mayo Institute of Technology, 18-23 June, pp. 289-304. [ Links ]

MENDES, A., 2007b. The Portuguese Forests. Working Paper. Porto: Universidade Católica do Porto, 271 pp. [ Links ]

MENDES, A., 2003. O Sector Florestal Português – Necessidades de organização colectiva do sector privado e medidas de política pública urgentes. In: J. Portela and J. Caldas (Eds.), Portugal Chão. Oeiras: Celta Editora, pp.359-372. [ Links ]

NAIL, S., 2008. Woodland Participation and Community Building. In: Forest Policies and Social Change in England. Springer, 6: 231-266. [ Links ]

RADICH, M.C., BAPTISTA, F.O., 2005. Floresta e Sociedade: Um percurso (1875-2005). Silva Lusitana 13(2): 143-157. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, C., COELHO, C., VALENTE, S., CARVALHO, T., FIGUEIREDO, E., 2011. Do stakeholders know what happens to soil after forest fires? A case study in Central Portugal. In A.B. GONÇALVES, A. VIEIRA (Eds.). Fire Effects on soil Properties, Proceedings of the 3rd International Meeting of Fire Effects on Soil Properties 15-19 March, Universidade do Minho, Guimarães, pp. 119-122. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, C., FIGUEIREDO, E., COELHO, C., VALENTE, S., CARVALHO, T., 2010. Uma árvore não faz a floresta? Análise da percepção dos proprietários florestais face aos incêndios e sua actuação. In: E. FIGUEIREDO, E. KASTENHOLZ, M.C. EUSÉBIO, M.C. GOMES, M.J. CARNEIRO, P. BATISTA, S. VALENTE (Org.). IV Congresso de Estudos Rurais – Mundos Rurais em Portugal: Múltiplos Olhares, Múltiplos Futuros 4-6 February, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, pp. 172-173. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, C., VALENTE, S., COELHO, C., FIGUEIREDO, E., 2012. Visions of local forest technicians' about forest management policies. In: XIII World Congress of Rural Sociology. Lisboa: International Rural Sociology Association, Instituto Superior de Agronomia and Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, 29 July to 4 August. [ Links ]

RICKENBACH, M., ZEULI, K., STURGESS-CLEEK, E., 2005. Despite failure: The emergence of "new" forest owners in private forest policy in Wisconsin, USA. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 20(6): 503-513. [ Links ]

SCHWILCH, G., HESSEL, R., VERZANDVOORT, S. (Eds), 2012. Desire for Greener Land. Options for Sustainable Land Management in Drylands. Bern, Switzerland, and Wageningen, The Netherlands: University of Bern - CDE, Alterra - Wageningen UR, ISRIC - World Soil Information and CTA - Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation. [ Links ]

SERBRUYNS, I., LUYSSAERT, S., 2006. Acceptance of sticks, carrots and sermons as policy instruments for directing private forest management. Forest Policy and Economics 9(3): 285-296. [ Links ]

SILVA, J.S., DEUS, E., SALDANHA, L., 2008 Evolução dos incêndios florestais em Portugal, antes e depois de 2003. In: J.S. SILVA, E. DEUS, L. SALDANHA (Eds.), Incêndios Florestais 5 anos depois de 2003. Liga para a Proteção da Natureza, Autoridade Florestal Nacional, Coimbra, pp. 13-47. [ Links ]

VALENTE, S., COELHO, C., 2012. Forest Intervention Areas (ZIF): A solution for forest management in Portuguese rural areas. In XIII World Congress of Rural Sociology 29 July to 4 August, International Rural Sociology Association, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Instituto Superior de Ciências Sociais e Políticas, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, Lisboa. [ Links ]

VALENTE, S., COELHO, C. SOARES, J., 2012. Forest Intervention Areas (ZIF): a new approach for forest management in Portugal. In European Geosciences Union General Assembly 2012, 14 (EGU2012-894), 22-27 April, Vienna. [ Links ]

VALENTE, S., SOARES, J., COELHO, C., 2011. Planeamento e Gestão Sustentável do Território: Aplicação da Metodologia WOCAT no Concelho de Mação. In E. FIGUEIREDO, E. KASTENHOLZ, M.C. EUSÉBIO, M.C. GOMES, M.J. CARNEIRO, P. BATISTA, S. VALENTE (Coord.), O Rural Plural: olhar o presente, imaginar o futuro. 100Luz, Castro Verde, pp. 355-368. [ Links ]

WOLLENBERG, E., MOELIONO, M., LIMBERG, G., IWAN, R., RHEE, S., SUDANA, M., 2006. Between state and society: Local governance of forests in Malinau, Indonesia. Forest Policy and Economics 8(4): 421-433. [ Links ]

Entregue para publicação em fevereiro de 2013

Aceite para publicação em agosto de 2013

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted within the framework of the Ph.D. Grant of Sandra Valente (SFRH/BD/47056/2008). Logistic support was provided from EC-DG RTD, 6th Framework Research Programme (sub-priority 1.1.6.3), Research on Desertification, project DESIRE (037046): Desertification Mitigation and Remediation of Land - a global approach for local solutions and from ForeStake project (PTDC/AGR-CFL/099970/2008), funded by FCT with co-funding FEDER, through COMPETE (Programa Operacional Fatores de Competitividade).

We would like to thank: António Louro, Nuno Bragança, Inês Mariano and João Fernandes for kindly supporting all the field work and providing all needed information; Teresa Carvalho for helping in questionnaires implementation; Gudrun Schwilch and Hanspeter Liniger, for their valuable support in using WOCAT questionnaires and database; Silva Lusitana reviewers for their help in improving this manuscript. Finally, a grateful acknowledgement is owed to all anonymous respondents who made this research possible.

NOTAS

1 Decree-Law no. 127/2005, August 5. Diário da República no. 150, I Series A: 4521-4527.

2 Decree-Law no. 15/2009, January 14. Diário da República no. 9, I Series A: 254-267.

3 Overall budget for the implementation of 1 ZIF with 1.000 ha in about 5 years: 1.000.000 (SCHWILCH et al., 2012).

4 The survey was developed under the framework of RECOVER project (PTDC/AGR-AAM/73350/2006) - Immediate soil management strategy for recovery after forest fires, funded by Science and Technology Foundation (FCT). It was implemented to 15% of forest owners living in the Pessegueiro do Vouga parish (N=28). Results were described in RIBEIRO et al. (2010; 2011).

5 The survey was developed under the framework of ForeStake project (PTDC/AGR-CFL/099970/2008) - The role of local stakeholders to the success of forest policy in areas affected by fire in Portugal, funded by FCT. It was implemented to all GTF and OPF responsible by ZIF (N=339). Preliminary results were presented in RIBEIRO et al. (2012).

6 The survey was implemented to 55% of ZIF management entities (N=24). Results are described in DEUS (2010).

7 A national-wide survey was implemented to address social perceptions about forest fires (N=3108).